In a Middle East wracked by coups d'état and civil insurrections, the Republic of Turkey credibly offers itself as a model thanks to its impressive economic growth, democratic system, political control of the military, and secular order.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan effectively bought the June 2011 elections by pumping credit into the Turkish economy. |

Islamists without brakes: When four out of five of the Turkish chiefs of staff abruptly resigned on July 29, 2011, they signaled the effective end of the republic founded in 1923 by Kemal Atatürk. A second republic headed by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Islamist colleagues of the AK Party began that day. The military safely under their control, AKP ideologues can now pursue their ambitions to create an Islamic order.

An even worse opposition: Ironically, secular Turks tend to be more anti-Western than the AKP. The two other parties in parliament, the CHP and MHP, condemn the AKP's more enlightened policies, such as its approach to Syria and its stationing a NATO radar system.

Looming economic collapse: Turkey faces a credit crunch, one largely ignored in light of crises in Greece and elsewhere. As analyst David Goldman points out, Erdoğan and the AKP took the country on a financial binge: bank credit ballooned while the current account deficit soared, reaching unsustainable levels. The party's patronage machine borrowed massive amounts of short-term debt to finance a consumption bubble that effectively bought it the June 2011 elections. Goldman calls Erdoğan a "Third World strongman" and compares Turkey today with Mexico in 1994 or Argentina in 2000, "where a brief boom financed by short-term foreign capital flows led to currency devaluation and a deep economic slump."

Sending the Mavi Marmara to Gaza amounted to an intentional provocation. |

Looking for a fight with Israel: In the tradition of Gamal Abdel Nasser and Saddam Hussein, the Turkish prime minister deploys anti-Zionist rhetoric to make himself an Arab political star. One shudders to think where, thrilled by this adulation, he may end up. After Ankara backed a protest ship to Gaza in May 2010, the Mavi Marmara, whose aggression led Israeli forces to kill eight Turkish citizens plus an ethnic Turk, it has relentlessly exploited this incident to stoke domestic fury against the Jewish state. Erdoğan has called the deaths a casus belli, speaks of a war with Israel "if necessary," and plans to send another ship to Gaza, this time with a Turkish military escort.

Stimulating an anti-Turkish faction: Turkish hostility has renewed Israel's historically warm relations with the Kurds and turned around its cool relations with Greece, Cyprus, and even Armenia. Beyond cooperation locally, this grouping will make life difficult for the Turks in Washington.

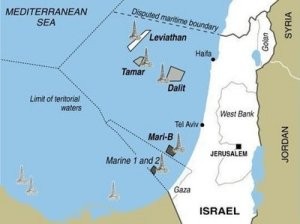

Asserting rights over Mediterranean energy reserves: Companies operating out of Israel discovered potentially immense gas and oil reserves in the Leviathan and other fields located between Israel, Lebanon, and Cyprus. When the government of Cyprus announced its plans to drill, Erdoğan responded with threats to send Turkish "frigates, gunboats and … air force." This dispute, just in its infancy, contains the potential elements of a huge crisis. Already, Moscow has sent submarines in solidarity with Cyprus.

The Leviathan gas field is the largest of several found recently between Cyprus and Israel.

Other international problems: Ankara threatens to freeze relations with the European Union in July 2012, when Cyprus assumes the rotating presidency. Turkish forces have seized a Syrian arms ship. Turkish threats to invade northern Iraq have worsened relations with Baghdad. Turkish and Iranian regimes may share an Islamist outlook and an anti-Kurd agenda, with prospering trade relations, but their historic rivalry, contrary governing styles, and competing ambitions have soured relations.

While Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu crows that Turkey is ""right at the center of everything," AKP bellicosity has soured his vaunted "zero-problems" with neighbors policy, turning this into a wide-ranging hostility and even potential military confrontations (with Syria, Cyprus, and Israel). As economic troubles hit, a once-exemplary member of NATO may go further off track; watch for signs of Erdoğan emulating his Venezuelan friend, Hugo Chávez.

That's why, along with Iranian nuclear weapons, I see a rogue Turkey as the region's greatest threat.

Mr. Pipes (www.DanielPipes.org) is president of the Middle East Forum and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University. © 2011 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Sep. 27, 2011 update: For a miniature example of AKP bellicosity, note the fracas at the United Nations in recent days as the prime minister and foreign minister bounded about the place with their bodyguards, making trouble.

Sep. 28, 2011 update: A reader, Selami Zorlu, took issue with the economic analysis in the above article. As I depended there on the work of David P. Goldman, I turned to Mr. Goldman to reply, which he did. The exchange follows.

Selami Zorlu's critique

Today i read your article titled "Is Turkey going rogue" iin the National Post. You are offering very stong and accurate insight into a variety of issues. But you got a couple of arguments wrong in the process.

I am an economist and banker. I would sum up my main area of expertise/responsibility as "Turkish debt". As much as I dislike the AKP and its ideas, what they did (or tried to do) in the economy was exactly the opposite of what you suggest in your article. I am 37 and for the first time in my life I witnessed the notion of a Turkish state budget in the black under these guys.

Your assertion that "the party's patronage machine borrowed massive amounts of short-term debt to finance a consumption bubble" is wrong, to say the least. Do you mean they borrowed money and rationed to the public so they can spend? :) I'm kidding. But the reality is that Turkish foreign debt has in fact shrank, again under these guys, when looked at in terms of who did the borrowing. The Turkish public debt is largely owed to the Turkish public, and the portion that constitutes foreign debt makes up the minority of Turkey's foreign debt. It is indeed the private sector that borrowed heavily in the past 8 years or so due to the fact that USD borrowing was extremely cheap. Banks in turn lent that money in the domestic markets as cheaper credit, which fuelled the boom you mention in your article. The AKP has been trying hard to curb that growth as they are very aware of the dangers.

On the other hand, the infamous Current Account Deficit (CAD) is a matter of intellectual debate. If you'd said "balance of payments" is unsustinable then it'd be a different debate. But to suggest CAD is unsustainable is in my humble opinion a paradox in itself. Because the maths is simple: if you couldn't finance it you wouldn't accumulate more CAD. It is because it is financeable that the Turks (and others) have been able to widen their CAD. I would draw your attention to the following items in the BOP calculation: FDI, portfolio investments and the "others" item, which was massive in Turkey's Q32011 figures. Bottomline, Turkey can finance its Balance of Payments (and in turn the CAD deficit) and will sustain it as long as its private sector can keep borrowing. If there's a problem along the line, it will be a credit problem, not a country event (i.e. private sector defaulting on loans granted by foreign public sector). I would strongly recommend you to see the Australian case in the CAD literature.

All in all, I believe your article was a good one in terms of drawing attention to the dangers posed by the current Turkish confidence mixed with lack of depth and intellect. It is indeed dangerous.

David Goldman's reply:

Selami Zorlu may be complacent about Turkey's economic situation, but markets are already forecasting a severe setback for the Turkish economy. Turkey's lira fell by a quarter between its November 2010 peak and Sept. 22, the worst performer among all the major currencies. Its stock market, meanwhile, has fallen in dollar terms by 40%, far more than the 25% decline in the MSCI Emerging Market Index, the worst performance among all the index components.

1. It is patently false to argue that the AKP is "trying hard to curb" domestic credit growth. On the contrary, the regime aggressively promoted consumer lending. The banks closest to the AKP, that is, the four Islamic Banks (or "participation banks") have increased their consumer loans at a much faster rate than the conventional banks. In the year through September 16, consumer loans by the Islamic banks rose by 53%, according to the Central Bank's data base. Commercial banks' consumer lending grew by 36%. The Islamic banks have lent TRY 5 billion to consumers, about a quarter as much as the commercial banks. As Sharia-compliant banks, the participation banks are aligned with the Islamist AKP. One of them, Bank Asya, is controlled by the Fethullah Gülen movement.

2. The closer we look at Turkey's enormous current account deficit (at 11% of GDP during the second quarter of 2011), the more malignant it appears. It is one thing for a developing country to run a trade deficit in order to import capital goods that contribute to future productivity. But Turkey's imports are a pure consumer bubble.

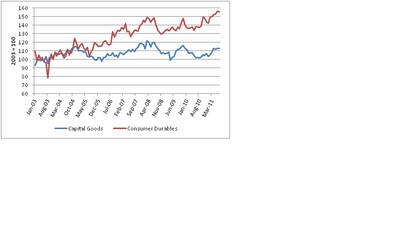

As we observe the chart below, the surge in Turkey's imports was concentrated on consumer durables. Imports of capital goods remain well below the pre-crisis peak. Capital goods imports barely changed from their 2003 level, while consumer goods imports rose by more than half. Turkey ran up a current account deficit equivalent to nearly half its total import volume, while reducing imports of capital goods that would have added to future productive capacity. The Erdogan regime, that is, presided over a classic bubble in imported consumer goods.

Unit Value of Turkish Imports of Capital Goods and Consumer Durables (Index 2003 = 100)

Source: Central Bank of Turkey

The country's overall debt levels remain low compared to the weaker European countries, but the growth rate is alarming. To correct it will require a severe retrenchment of domestic consumption.

As Prof. Murat Üçer of Koc University wrote in the Fall newsletter of the Center for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (EDAM),

A serious and probably quite painful 'adjustment' is inevitable in the short-term, in order to bring current account deficit to more 'normal' levels….This can't happen with a weaker currency alone; growth will also have to slow visibly. Second, an excessive CAD level points to a structural weakness in the economy. It simply attests to our inability as a nation, to put forth enough of a presence in the global supply chain of goods and services. Put differently, it implies that our average dollar-based income – per capita as well as per worker, which runs around $10,000 and $30,000, respectively -- is simply too high, compared to our average productivity levels. By this interpretation, the current account deficit represents nothing but a structural deficit in our skills and institutions.

Turkey simply is not the economic powerhouse it likes to think it is, and the humbling of Turkey's economic prospects presages a similar humiliation in its global standing.

Selami Zorlu's response:

It is posted at "so Turks have bought new cars."