Terrorism is ordinary diplomatic language in the Middle East.

- Josette AliaOther Middle East states export dates, rugs, or oil; Syria exports trouble

- An American ambassador to Syria

The best introduction to the Syrian use of secret warfare is the story of a single incident, the near-successful destruction of an El Al plane in April 1986. Nizar Hindawi's attempt reveals a great deal about the Syrian government's methods; it also says something about its goals.

The Hindawi Operation

Background

Nizar al-Hindawi. |

Seeking refuge, he arrived in London in 1979. At first, he hoped to write for the Arabic press. This did not work out, in part because of a drinking problem. Failing to land a steady position, Hindawi took on odd jobs. For example, he worked in 1982 for two months as a messenger at a London-based Arabic newspaper, Al-'Arab. But he was fired for erratic behavior (locking up the teleprinter room and taking the key home in a fit of temper). Hindawi had other troubles too. He married a Polish woman and the couple had a daughter; but his wife left him and returned to Poland with the child.

Despondent, Hindawi hired himself out in the early 1980s to the Syrian government to make quick money. According to the British authorities, the Syrian ambassador to the Court of St. James's, Loutuf Allah Haydar, was personally engaged in recruiting Hindawi. The relationship began innocently enough, with Hindawi writing puff pieces on Syria. Then, one thing led to another and in late 1985 or so - about the time the Jordanian government refused to renew his passport - he went to Syria for two months' military training. Hindawi trained in a camp maintained by Abu Nidal near Dahir, a town of 15,000 east of Damascus.

The Operation Begins

In January 1986, Hindawi went to Damascus where he met Brig. Gen. Muhammad al-Khuli, the chief of air force intelligence, head of the National Security Bureau and a man widely believed to be Asad's closest advisor. (Khuli's portfolio also included foreign guests, Syrian Arab Airlines, covert operations, and Asad's personal protection.) In addition, Hindawi met Khuli's three assistants: Lt. Cols. Haytham Sa'id, Mufid Akhur, and Samir Kukash. A deal was cut: Hindawi would attack an El Al plane and in return the Syrians would help him in his efforts against the Jordanian government. Sa'id, the deputy chief of air force intelligence, was designated Hindawi's control officer.

At a subsequent meeting on 9 February 1986, Sa'id provided a first payment of $12,000 (the full amount for a successful operation was scheduled to be $250,000) and a Syrian "service" passport (an official passport good for only one trip at a time) made out in the name of 'Isam Shar'. Hindawi used his original Jordanian passport to travel extensively in the Soviet bloc but relied on his Syrian one to travel on two occasions to the United Kingdom.

He applied the very next day, 10 February, for the first visa. Each time, the Syrian Foreign Ministry backed Hindawi's visa applications to the British government with an official note of endorsement. According to one press report, the visas were granted in part through the connivance of a Syrian agent in the British embassy in Damascus. Hindawi made a dummy run to London in February, posing as a military procurement officer intending to buy spare parts for British Leyland Range Rovers. As part of his disguise as a diplomat, he even joined a London club.

Back in Damascus he met again with Haytham Sa'id, who showed him how to prepare a suitcase bomb by placing the detonator near the main charge in a false bottom; the explosive would then combust sympathetically. In other words, neither wires nor technical competence was needed. If caught, Sa'id told him, Hindawi should under no circumstances mention his Syrian connection. Instead, he was to portray himself as a drug runner. Violation of this instruction would lead to the elimination of a quarter of Hindawi's 500 family members living in Syria the very next day. Lastly, Sa'id gave Hindawi his telephone number, Damascus 336-068.

Before setting out on his London business, Hindawi appears to have proven his abilities by organizing the 29 March 1986 bombing of the Berlin-based German-Arab Friendship Society, an operation carried out primarily by his brother Ahmad Nawwaf al-Mansur al-Hasi.

Hindawi applied for a second British visa on 2 April, again using his false passport. This time he posed as a Syrian foreign ministry accountant vacationing in Great Britain. The visa was granted the next day and he flew to London as 'Isam Shar' for a second time on 5 April. Haytham Sa'id's brother, Ghasim, accompanied him and both posed as members of the Syrian Arab Airlines flight crew. Hindawi stayed his first two nights with the crew at the Royal Garden Hotel, in a room paid for by the airline. On 6 April, he took delivery of the detonator and travel bag he was to use. The bag was stored with his father, Nawwaf Mansur, who also lived in London.

Enter Ann-Marie Murphy

Ann-Marie Doreen Murphy. |

Hindawi made her pregnant twice. The first pregnancy, which occurred early in 1985, ended in miscarriage. He then disappeared between April and September 1985. She became pregnant a second time in November 1985. But before she discovered her condition, Hindawi had left the country again. When he called from Berlin in January 1986 and learned what had happened, he wanted nothing to do with it. Hindawi pressed her, rather, to abort the fetus. In Murphy's words, "He did not want to know about it. He wanted me to get rid of the thing." This she refused to do. Instead, she began making plans to return by herself to Ireland.

Another picture of Ann-Marie Doreen Murphy. |

Hindawi demanded that she not tell anyone about their plans and got unreasonably angry on learning that she had informed two of her sisters, a friend, and the friend's husband. Further, he wanted to keep their story secret from the airline and from Israeli customs personnel. With this in mind, he supplied her with answers to the standard questions she would be asked going to Israel. Then he quizzed her and coached her to give the right replies.

Hindawi helped her prepare for the trip in other ways too. He told her that she would be met by a woman named Angela at the airport. He paid for her passport, bought her new clothes, and gave her the money for a ticket to fly to Israel on El Al flight 016 on Thursday, 17 April. (The day may have been picked because of its proximity to Passover and the greater likelihood of a full flight.) On 15 April he stood outside the Superstar travel agency on Regent Street while Murphy bought a ticket inside. On the evening of the 16th, he brought her a wheeled suitcase (a "holdall" in British parlance), courtesy of the Syrian embassy. Arguing that her own suitcases were too big, Hindawi convinced her to use this bag instead.

In addition to men's clothing, the suitcase contained a false bottom containing a half-inch thick sheet of Semtex, the powerful Czechoslovak-made plastic explosive which subsequently blew up a Pan Am jumbo jet over Lockerbie, Scotland and a UTA plane over West Africa. Being almost wire-free, Semtex is virtually undetectable by airport X-rays. The 3½ pounds of Semtex was taped to the bottom of the bag; police tests showed that some of Hindawi's own hair was trapped under the tape. (This small point conclusively refutes the Syrian claim that Israeli intelligence had switched Murphy's bag to stage a set-up.)

As he helped Murphy pack, Hindawi inserted a Commodore scientific calculator in the suitcase, telling her it was a present for a friend in Israel. In fact, while this mechanism was a functioning calculator, a circuit board timer and 1.7 ounces of Semtex had been added. The calculator, when outfitted with a battery, would serve as trigger for the suitcase bomb. But so cleverly was the device put together, the calculator could be tested by a guard and it would work. According to Scotland Yard, the sophistication of this bomb almost certainly implies that it had been put together in Damascus, though some accounts suggested the device had been assembled in the Syrian embassy in London.

The Operation

The next morning, 17 April, Hindawi got up early and, dressed in a brown suit, black shoes, and a beige coat, took a taxi to Murphy's apartment in Kilburn, where he arrived about 7:30 a.m. At precisely 8:03 a.m., while on the way to Heathrow Airport, a visibly nervous Hindawi put a battery into the calculator, arming the detonator to go off five hours and one minute later, at 1:04 p.m., GMT. The flight was scheduled to leave at 9:50 a.m.; in all likelihood the plane would have been 39,000 feet over Austria when the bomb went off; all 375 passengers would certainly have been killed. Hindawi pushed the calculator to the bottom of the bag, where it would be closest to the main charge, and so most certain to set it off.

When the couple arrived to the airport, at about 8:30 a.m., Hindawi paid the taxi and placed the suitcase on a cart. The couple spent some time chatting in the terminal before Hindawi gave the pregnant woman a quick kiss on both cheeks, then bade her a casual goodbye - "See you later." He then headed back for the Royal Garden Hotel, intending to pose again as a crew member on the airline's 2 p.m. flight that afternoon back to Syria.

It was no accident that Murphy was caught, and in large part because her actions roused suspicions. To begin with, her ticket had been rebooked, an action which automatically triggers special scrutiny by El Al. Then the security interview at Gate B23 was a calamity. Murphy passed through X-ray inspection without problems and reached the gate with the bag still on an airport cart. There she waited calmly until about 9:10 a.m., when an El Al agent ran through the company's standard questions with her. First, when asked whether she had packed her bags by herself, she answered in the negative, setting off bells. As reconstructed by Neil C. Livingstone and David Halevy, the following exchange went approximately like this:

"What is the purpose of your trip to Israel?"

Remembering what she had been told to answer, she answered, "For a vacation."

"Are you married, Miss Murphy?"

"No."

As unmarried pregnant Irish women do not often go for vacation in Israel, the agent probed further. "Traveling alone?"

"Yes."

"Is this your first trip abroad?"

"Yes."

"Do you have relatives in Israel?"

Hesitating, Murphy relied, "no."

Every reply increased the passenger's oddity. "Are you going to meet someone in Israel?"

"No.

"Has your vacation been planned for a long time?"

"No."

Quizzing her now with some intensity, he asked: "Where will you stay while you're in Israel?"

"The Tel Aviv Hilton."

"How much money do you have with you?"

"Fifty pounds [about $70]."

"Do you know how much a room costs at the Hilton?" Then, not waiting for an answer (it costs at least $100 a night), he asked, "Do you have a credit card?"

"Oh, yes," she replied, and proceeded to produce from her purse an identification card for check-cashing purposes.

This was too much. Convinced that something was amiss, the agent emptied the bag and found it "quite heavy," with "a sort of double bottom." He sent Murphy to be body-searched and took her bag to a staff room. Although she had nothing on her person, inspection of the bag turned up a plastic bag at the bottom full of a yellowish, oily substance - Semtex. A closer look then turned up the detonator in the Commodore calculator.

Aftermath

Had the bombing been successful, Hindawi would have been out of Britain that afternoon. But Murphy was alive to tell police about Hindawi and news of the failed attempt got out in the morning. Hindawi heard of it while waiting on a Syrian Arab Airline bus to go to Heathrow. Rather than continue with the planned escape, Hindawi's intelligence escort took him to the Syrian embassy where Ambassador Loutuf Allah Haydar met him and complimented him on his "good work." Hindawi handed a letter to the ambassador who telephoned Damascus for instructions. Haydar then had Hindawi taken out the back door to a private apartment at 19 Stonor Road in West Kensington. At the apartment, an embassy guard cut and dyed his hair; Hindawi then spent the night there. The next day, two men came to get him at 5:30 a.m. to take him back to the Syrian embassy. He bolted before they got him in the car - preferring not to trust his fate to the tender mercies of the regime in Damascus.

He fled to the London Visitors' Hotel in the Holland Park section of town, where he registered for one night, paid £24, and was given room 18. The duty manager recognized Hindawi from his picture in all the newspapers and alerted the hotel's owner, Jordanian-born Na'im 'Awran. 'Awran was a business acquaintance of Nizar's older brother Mahmud, a chartered accountant working in the Qatar embassy in London. 'Awran called Mahmud and insisted he come to the hotel. Together, the two convinced Nizar to give himself up to the police. Accepting their counsel, Nizar returned to his room and calmly waited for the authorities to arrive. Two plainclothes policemen turned up and escorted him away.

After initially trying to fool the police with a story about having been engaged in no more than smuggling drugs to Israel, Hindawi eventually provided a forthright confession, recounting the details of his February meeting with Khuli and proving his bona fides by supplying Khuli's personal telephone number. According to one account, he also testified that Hafiz al-Asad had personally ordered the attack on the El Al plane. Hindawi went on to tell what he knew about Syrian Arab Airline crews bringing explosives, guns, and drugs into the United Kingdom.

Although Hindawi subsequently recanted, perhaps remembering Sa'id's threat against his family, the information in his confession was subsequently confirmed. Further, his capture implicated his brother Ahmad and cousin 'Awni. The police found in Hindawi's apartment Ahmad's Berlin telephone number. A West German court later found Hasi guilty of the 29 March 1986 explosion at the German-Arab Friendship in West Berlin that killed two. He was also implicated in the bombing a week later of La Belle Discoteque in Berlin. Hasi too worked for the Syrians: he admitted having picked up explosives in the kitchen of the Syrian embassy in East Berlin. Then the police intercepted a letter Hindawi sent from jail to his cousin in Genoa, 'Awni al-Hindawi, asking him to "get the Syrians to take hostages and get him out of prison." 'Awni was arrested for complicity in the Berlin bombing.

Conclusions

It should be noted that the Asad regime was involved at every step of the operation, having trained Hindawi in Syria, provided him with a passport, supported his visa applications, disguised him as a Syrian Arab Airlines crew member, given him explosives and the bag with a false bottom, and helped him after the effort had failed. Hindawi further implicated the government by asking it to capture British hostages on his behalf. Direct participation by Damascus is somewhat unusual, but the Hindawi case in other ways too typifies the Syrian use of terror - the use of a non-Syrian national; the brazen exploitation of diplomatic immunity; the use of a high technology explosive; reliance on a local female; and the operative's fear of his handlers. The judge in Old Bailey put it correctly when sentencing Hindawi, "This was a well-planned, well-organized crime which involved many others than yourself, some of them in high places."

The judge was right, though there was much speculation that Hindawi's effort was part of a rogue operation or "a piece of private enterprise by officials in the middle reaches of Syrian intelligence." One writer even deemed it certain that Asad "and the rest of his government knew nothing about the operation until they heard the news on the radio."

In fact, there are several reasons to believe that Hafiz al-Asad himself oversaw the London operation. First, Hindawi initially testified to this effect. Second, it seems inconceivable that Asad would let underlings take steps which could well have precipitated war with Israel. Third, Muhammad al-Khuli was one of Asad's closest aides - far from a mid-level bureaucrat. Fourth, had the attempted bombing been a rogue operation, Khuli and his aides would have paid some price, but they seem not to have been punished at all. Finally, Asad personally oversees all important operations, so it is inconceivable that one of this magnitude would take place without his knowledge. In the words of a former member of the Syrian Ba'th Party, "if it really was Syria, then it must have been Assad himself. In crucial security matters he looks into every detail."

In conclusion, it appears that the British government seems to have engaged in some deception of its own. While Scotland Yard announced that Murphy had been caught as a result of "a routine security check," there is good reason to believe that much more lay behind the event. In particular, it appears almost certain that the British in March 1986 had intercepted a Syrian embassy request for assistance to support Hindawi's planned operation. Hindawi had therefore been under around-the-clock surveillance since he arrived in the United Kingdom on 5 April. Also, American planes based in Great Britain had bombed Libya just two days earlier, and fears of retaliation caused the airport to be on a high security alert. As an unidentified U.S. government specialist put it, "The Israelis were expecting Miss Murphy. It was no surprise when she and her bag arrived. It was certain to be gone over again and again."

Terrorism in the Context of a Foreign Policy

Why does the Syrian government sponsor activities like Hindawi's? How do such operations forward the state's interests? How can Damascus be induced not to support terrorism?

These are complex questions, but the place to start is with a description of the Asad regime and its priorities. Since coming to power in November 1970, Asad's first goal has been to retain power. That is a constant challenge, for the regime's top positions are staffed primarily by 'Alawis, members of a small and despised religious minority much resented by the Sunni Muslim majority. Because they benefit disproportionately from Asad's rule, 'Alawis fear what would happen should they lose control to the Sunnis. This fear goes far to explain the bellicose nature of Syrian foreign policy. The effort to eliminate Israel appeals to the displaced Sunnis and gives them something in common with the regime. Too, Damascus' attempts to control the region known as Greater Syria (which includes Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan) are broadly popular. And alignment with the Soviet Union has long made it easier to repress the Sunnis whenever they get out of line.

Each of these policies also implies a need for covert warfare. The Israelis are too strong to attack by conventional means, so irregular methods take their place. Greater Syria calls on irredentist efforts against Lebanon and Jordan, plus the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The Soviet connection leads to campaigns of sabotage against Turkey and the West. Given this aggressiveness, terrorism - rather than conventional forms of military violence - becomes a useful instrument of statecraft. It is inexpensive; it permits actions of a sort which a state could not possibly back openly; and it intimidates opponents.

In Asad's hands, terrorism has often influenced the actions of foreign states. In Lebanon, it pushed out Western and Israeli troops in 1982-84, and it helped Damascus gain and keep control over most of the country's territory. In the Arab-Israeli conflict, it is instrumental in preventing Arab states from adopting more accommodating policies toward Israel; specifically, it blocked King al-Husayn of Jordan from entering peace negotiations with Israel. In the Persian Gulf, it keeps the money coming. With Libya and Iran, it boosts an otherwise frail alliance. With regard to the Soviet Union, it increases Syrian power and enhances Asad's utility.

Terror also serves more targeted purposes. On one occasion, in September 1986, Syrian officials offered to do what they could to curb terrorism in France - but only in return for economic aid. The spate of Syrian-backed incidents between April and September had, according to Israeli analyst Moshe Zak, two purposes: to prevent an Israeli-Egyptian-Jordanian dialogue and to eliminate Israeli influence over southern Lebanon. Further, he argues, the two are related: "Syrian intelligence seems to believe that the explosions in Paris are a good background for softening France's position on Lebanon, and for making the Elysée Palace exert pressure on Israel" to leave Lebanon.

Asad began sponsoring terror even before he became ruler of Syria in 1970. His sponsorship of Palestinian groups in the mid-1960s, for example, contributed directly to the outbreak of the Arab-Israeli war of June 1967. Since Asad became ruler of Syria, his reliance on this tool can be divided into four distinct eras.

Early 1970s-1982. Syrian nationals participated in Damascus's operations, most of which were directed either against Israeli and Jewish targets or against Arabs. The latter included such enemies of the Syrian state as Syrian dissidents and pro-Arafat Palestinians; it also included officials of states which Damascus wanted to intimidate (such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait).

1983-85. Two major changes in the modus operandi took place in 1983, both connected to the 1982 war in Lebanon. First, the Syrian government became the international fulcrum for terrorism, having taken over this role from the PLO. In all, an estimated 3,500 desperadoes moved to Damascus after late 1983. Second, the Syrian authorities began taking great pains not to use Syrian nationals in their terrorism campaigns; Syrians acted only as supervisors, while non-Syrians did the dirty work.

1986. During a brief period, especially in the spring of 1986, Asad directly involved relied on his own intelligence services. At one point, one of the highest intelligence officials, Col. Haytham Sa'id, even traveled to Berlin to oversee an operation. Despite an elaborate and cunning network, Syrian involvement was repeatedly discovered - at one point late that year, trials dealing with Syrian-sponsored terror were pending in London, Madrid, Paris, West Berlin, Genoa, Vienna, Istanbul, and Karachi. The regime became internationally notorious and eventually seems to have found the price too high. Bombs in Beirut are one thing; in Paris, quite another. Smarting from the uproar, Asad retreated to the Middle East.

1987 to date. Syrian activity reverted to a mix of the first and second periods. As in the first period, terror is mainly deployed in the Middle East (in Turkey and Lebanon, against Palestinians and Israelis); this keeps Damascus out of the headlines and lowers political costs. As in the second period, the regime relies mainly on proxies. After the ambitious experimentation of 1983?86, this blend seems to offer a stable long-term approach to terrorism.

Patrons and Partners

Asad made Syria virtually a member of the Soviet bloc; this explains not just such general behavior as the virulently anti-Western stance of the Asad government, but also specific Syrian terrorist activities that otherwise would be difficult to account for. The most important of these must be the long-term Syrian efforts to destabilize Turkey, which benefits the Kremlin far more than Asad.

In return, the Soviet bloc provides a variety of assistance to Syrian-backed terrorism. This includes the weapons themselves (notably Semtex, a highly malleable explosive) and training in their use. Until recently, East German and Bulgarian "security advisors" work in Syrian camps, while members of some terrorist organizations went to the Soviet Union and East Europe for specialized instruction; some of them even learned Russian or other East bloc languages.

But the ties between the Syrian and Soviet states have gone far beyond material aid. Despite what Harvey Sicherman has called a "history of fine betrayals" between Syria and USSR, extensive evidence suggests that the U.S.S.R. and its clients have a major, though non-specific role in encouraging the Syrian use of terrorism. They provide him with a backing that increases his confidence to take risks. Not only does he know his enemies will think long and hard before taking on the missile batteries around Damascus or Soviet anger, but he has the political and psychological backing of a world-wide network of states and movements. Unlike other risk-taking and bellicose leaders in the Middle East (Khomeini, Qadhdhafi, 'Arafat), he has never been alone. There may be tensions on issues of the moment, but the relationship has proven itself enduring and deep.

Within the Middle East region, Damascus affiliates primarily with the Iranian and Libyan governments. The Iranian connection has particular importance in Lebanon. Boeing 747s belonging to the Iranian Air Force fly to Damascus carrying manpower, arms, and funds for Iran's operations in Lebanon. These are then taken by convoys of trucks, using military roads to avoid custom checks and border searches, to the Biqa' Valley in Lebanon. Radical fundamentalist Muslim groups such as Islamic Jihad, Islamic Amal, and Hizbullah depend on this arrangement for nearly all their supplies. In return for permitting this access, plus providing help of its own, the Syrian government exercises a large measure of control over Iran's Lebanese allies.

Thus, in early October 1983, about three weeks before the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut were blown up, a special flight is reported to have arrived in Damascus from Tehran with fifty Iranian operatives aboard. They were immediately taken to Baalbek in Syrian-controlled Lebanon and from there found their way to Beirut. Actual planning for the attack involved both Syrian and Iranian agents. Secretary of Defense Caspar W. Weinberger summed up the alliance by noting that those responsible for the Marine barracks explosion were "basically Iranians with sponsorship and knowledge and authority of the Syrian government."

As for three-way cooperation, it appears that Damascus cooperates with both the Libyan and Iranian governments in backing the Abu Nidal organization. According to a pro-Syrian Palestinian, the three states find it advantageous jointly to help this group because it "provides them with an Arab force that distances them from any public responsibility." According to an Israeli expert on terrorism, "Libya buys, stores, and distributes weapons through its pouch; Syria provides the logistical intelligence and training needed for such an attack; Iran provides the suicide commandos and some funding."

Cooperation can be even more broadly based: some leading terrorists have a mysterious stamp on the sixth page of their passports; it shows an airplane, the date "30 nov. 1984" and the word "Casa-Nouasseur." According to one report, this gets them in, no questions asked, to many states in the Middle East and North Africa.

While such instances of cooperation do take place, terrorism remains a highly secretive world in which states normally go it alone, especially on the operational level. A French counter-espionage official used an analogy to explain the cooperation between terrorist groups: they resemble the firms making the same produce which normally compete but sometimes band together as members of a trade association to cooperate.

In all, Asad prefers alliances with small groups that he can dominate, and these have a far larger role in his secret warfare than do other states.

Organizations

Most Syrian-sponsored terrorism since 1983 has been undertaken by members of organizations based in Lebanon that influenced, if not controlled, by the Syrian government. An assistant to Husayn Musawi of Islamic Amal explained the extent of Syrian control in 1984: "We don't have freedom of action. Our operations are not approved if they do not serve the interests of Damascus." A December 1986 Department of State report explains the advantages of this setup:

Available evidence indicates that Syria prefers to support groups whose activities are generally in line with Syrian objectives rather than to select targets or control operations itself. Damascus utilizes these groups to attack or intimidate enemies and opponents and to exerts its influence in the region. Yet at the same time, it can disavow knowledge of their operations.

In this way, Asad exerts effective control while he can simultaneously disclaim responsibility - a perfect combination.

In addition to plausible deniability, indirect sponsorship makes it possible to add manpower and skills. The proxy groups can call on many more cadres of devoted followers than can the military dictators in Damascus. Indirect sponsorship also permits Asad to play an intermediary role. Time and again, he assumes the mantle of statesman, talking to foreign leaders about ways to win the release of their hostages or stop terrorism on their territory, a posture that not only distances Asad from terrorist groups, but protects him from the full wrath of foreigners. No state dares punish him, for no one wants to alienate this key intermediary. Asad thus maintains good relations with many leaders - even those whose citizens suffer his predations.

Asad relies on three types of organizations:

Palestinian Organizations. After being pushed out of Lebanon in 1982, many factions of the PLO took refuge in Syria, where Asad brought them under the banner of the Palestine National Salvation Front (PNSF). The PNSF includes As-Sa'iqa, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (run by George Habash), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (Ahmad Jibril), the Democratic Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (Na'if Hawatma), and Abu Musa's Fatah dissidents. Other groups include the Arab Organization of the 15th of May for the Liberation of Palestine (Naji 'Alush) and Fatah - Revolutionary Command (Abu Nidal). The Syrians wooed Abu Nidal from his Iraqi patrons at the end of 1979 or early 1980, since which time he has been one of Asad's most active agents, conducting operations in almost every country of West Europe and many in the Middle East. He seems to have moved on to Libya in early 1987.

Arab Organizations. The Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), founded in 1932, enthusiastically approves of Asad because his goals coincide with its own plans to establish a single Syrian state covering the present territories of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan. Syrian backing permits the SSNP to control a portion of Lebanese territory to the south of Tripoli. Together with the Ba'th Party of Lebanon and the Lebanese Communist Party, it carried out nearly all of the fifteen suicide attacks against Israeli and South Lebanon Army troops that occurred in 1985.

Other groups include the (Druze) Progressive Socialist Party, the (Shi'i) Amal, the (Sunni) Nasirites, the Lebanese Revolutionary Brigades, the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Fraction (FARL), Arab Egypt, the Committee for the Defense of Democratic Liberties in Jordan the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Somalia, the Eritrean Liberation Front, and Polisario. Iraqi media have portrayed the Islamic Jihad Organization in Lebanon as a "cover for [Syria's] political crimes," and this is at least partially true.

Non-Arab Organizations. Since about 1980, the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) has received Syrian help - training bases, logistical support, and an operations center. When the group had to leave Beirut in 1982, it found new quarters in Syrian-controlled Lebanon. French intelligence is reported to believe that Damascus operates ASALA under Soviet supervision as a way of destabilizing Turkey and weakening the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The Kurdish Worker's Party (PKK), has served as Syria's main instrument against the Turkish government. The PKK, which was long the single most likely suspect in the February 1986 assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, has been called "a state within a state in Western Europe." Mehmet Ali Agca, the pope's assailant, testified that he was trained in Syria as a member of the Turkish Gray Wolves.

For operations in West Europe, Syrian agents have worked with the Red Army Faction of West Germany, Action Direct of France, the Red Brigades of Italy, the Basque ETA and the Fighting Communist Cells of Belgium. Further afield, help also goes to Zulfikar of Pakistan, the Pattani United Liberation Organization of Thailand, and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam of Sri Lanka. The Japanese Red Army spokesman lives in Damascus.

Should a convicted terrorist be let out of prison, chances are good he will head for Syrian-controlled territory. Magdelena Kopp of the Baader-Meinhof gang left a French prison and went via Athens right for Damascus. Within less than a month of his May 1985 release, Kozo Okamoto of the Japanese Red Army turned up in the Biqa' Valley. On his release, Bruno Breguet, an associate of "Carlos," flew straight to Damascus, where he was met on arrival by Syrian authorities and whisked away. In April 1986, Frédéric Oriach of Action Direct (and said to be the "inventor" of FARL) also went straight for Syria. "When all of these people are in town at the same time," writes G. Jefferson Price, "the lobby of the [Sheraton] hotel they favor acquires the atmosphere of a gangland meeting."

In all, according to Abdullah Öcalan, the PKK leader living in Damascus, there are some seventy-three such organizations that the Syrian government supports.

What is in it for the organizations? Why do they do Damascus's dirty work? Because the Syrian state (like any other) can confer great assistance to helpful groups. Benefits include: international access, money, high technology, and suicide bombers.

Diplomatic immunity permits the virtually unhindered transport of weapons, explosives, special tools, and money across international boundaries. Embassies double as safe houses and, in time of crisis, serve as inviolable sanctuaries. Unlike revolutionary groups, states have virtually inexhaustible amounts of money to spend on terrorism. From a state's view, this is a very inexpensive way of waging war. Payments to operatives appear to be good but not lavish.

States have access to expensive, fragile, and restricted equipment that private groups could not hope to acquire. Syrian agents have been caught with such highly explosive substances as Czechoslovak-made Semtex H, penthrite, and trityl. They also dispose of sub-machineguns, propellants, and a variety of remote-control devices. A workshop is said to exist in Damascus which specializes in the production of rigged Samsonite suitcases (which are then exchanged for those of unsuspecting passengers). States forge the passports of other states with special skill; thus, Georges Ibrahim 'Abdullah of FARL carried no fewer than five passports (two Moroccan, an Algerian, a Maltese, and a South Yemeni).

States can provide organizations with operatives prepared for suicide. Suicide bombers have two great advantages: they tend to cause the most damage and they usually do not survive to be captured (and reveal what they know). But there are few fanatics who volunteer to give up their own lives, and this is where the state has a role. The connection between state authority and suicide may not be obvious, but it can be very direct. Governments can use their powers of coercion to pick someone and offer him a choice: "Either you die a protracted, painful, and certain death in jail, your family is harassed or killed, and your name is dragged through the mud. Or you undertake this operation, in which case you have a chance of surviving. And if you die, you go quickly, your family is rewarded, and we make you a national hero." Under such circumstances, suicide attack is a rational and prudent choice.

Operations

In Syria proper, there are about 25 training camps for irregular warfare, five of them near Damascus. The Yarmuk camp is apparently the one most specifically dedicated to honing terrorist skills. Other bases, including Abu Nidal's base at Hammara, operate openly in the Biqa' Valley of Lebanon, an area under complete Syrian control. The training camps are supervised by the Syrian army and family members live in Palestinian camps in Damascus. A former member of Abu Nidal's group testified that training in Iraq (which presumably resembles what is found in Syria), the standard course lasts six months. A typical day consists of a ten kilometer run, four hours of physical workout and practice on such weapons as the Kalashnikov and the W.Z. 63 machine gun, followed by classes of indoctrination. In advanced training, "we learned how to kill people with a variety of methods, how to enter buildings quietly, stalk people through the streets and then escape."

The Syrian government usually arranges for passage from Lebanon or Syria to the site of the operation. It supplies a false passport (or two). In some cases, a Syrian intelligence (mukhabarat) official escorts the operative. Travel tends not to be direct: agents going to Rome, say, will go via Yugoslavia or Greece.

To gain maximum flexibility, Syrian authorities rely heavily on "sleepers," agents put in place far in advance of an operation. Sleepers commonly enroll in language school or university, an easy way to gain legal status in a foreign country, then gather information on targets and travel freely across borders. They exploit the large transient populations and easy political asylum laws of places like West Berlin. Sleepers sometimes set up two residences, one for normal life and the other as a safe house, the latter often near an airport. Lodgings sometimes multiply; police counted five apartments belonging to FARL in three West European countries. Numbered bank accounts in Switzerland are de rigeur. Presumably, the three SSNP members caught smuggling explosives from Canada into the United States in October 1987 were equipping a sleeper; and the same applies to Yu Kikumura, the Japanese Red Army caught with three powerful bombs on the New Jersey Turnpike in April 1988. More broadly, according to Pierre Marion, the head of the French General Directorate of External Security in the early 1980s, "There exists in the West, in Western Europe, and France in particular, permanent, dormant, logistical infrastructures" which are "activated for this or that particular operation."

The Syrians take great care to insure that they do not leave fingerprints. In some cases, they call on agents the very day of an operation or rely on "cutouts," individuals who take on a single task without knowing anything further about the operation. They also prefer to rely on the members of a single family, figuring that these are impenetrable by the police. Notable families in Syrian service include the 'Abdallahs of Lebanon and the Hindawi-Hasi clan of Jordan. Marion explained the Syrian method of operation: "Arms and bombs enter the country by diplomatic pouch. The terrorist arrives in the country by aircraft or train, hands in pocket [i.e., not carrying anything]. He meets his contact, who provides him with his targets and the means for accomplishing the mission."

Hafiz al-Asad keeps personal tab of terror operatives through his close associates. The camps and operations are under the supervision of Brig. Gen. Muhammad al-Khuli. On one occasion, an agent received instructions from Khuli that were signed by him personally. Control is further maintained by having operatives call the key figures in Damascus at critical moments, even from foreign countries.

The Syrian government relies on suicide squads for some of its most challenging operations. Asad delivered a remarkable speech in May 1985, telling a student audience:

I have believed in the greatness of martyrdom and the importance of self-sacrifice since my youth. My feeling and conviction was that the heavy burden on our people and nation . . . could be removed and uprooted only through self-sacrifice and martyrdom. . . . Such attacks can inflict heavy losses on the enemy. They guarantee results, in terms of scoring a direct hit, spreading terror among enemy ranks, raising people's morale, and enhancing citizens' awareness of the importance of the spirit of martyrdom. Thus, waves of popular martyrdom will follow successively and the enemy will not be able to endure them. . . . I hope that my life end will end only with martyrdom. . . . My conviction in martyrdom is neither incidental nor temporary. The years have entrenched this conviction.

Asad almost never brags; one may be sure that an announcement like this has an operational angle to it. Indeed, it appears that, beginning in March 1985, Asad and Khuli oversaw the training of specially picked suicide squads. Air pilots among the soldiers were trained in Lebanon and at the Minakh air base near the Turkish border. A number of captured terrorists have claimed that they wanted to drop out but dared not out of fear of recrimination by Damascus.

Some details about the Syrian-sponsored suicides became known in August 1987 when an Egyptian, 'Ali 'Abd ar-Rahman Wahhaba, gave himself up to the South Lebanon Army, an Israeli-backed force. Wahhaba told the following story: he went to Lebanon in the early 1980s looking for work; under repeated torture, he was compelled in 1984 to join a mukhabarat-backed group, Arab Egypt. In 1986 he underwent a two-week training course in weapons and explosives at a camp run by the chief sergeant major of Syrian intelligence in the Biqa' Valley. In January 1987 Wahhaba "was taken to Syrian television studios in Damascus, where he was given a prepared script. He was filmed saying he is going to commit suicide of his own free will in an attack against the Zionist enemy." 'Abdallah Ahmar, second in command in the Syrian Ba'th party, oversaw the filming; later, Gen. Ghazi Kan'an, the head of the mukhabarat in Lebanon, personally sent him off on a mission and blessed his undertaking. In the end, Wahhaba did not explode the 11 kilograms of TNT hidden in his jacket, but gave himself up to the South Lebanon Army.

Inexpensive as it is, training camps, special weapons, sleepers, and intelligence agents do drain the depleted resources of the Syrian government, so special financing is needed. The Syrians engage in a variety of forms of creative funding: arms-peddling, drug-running, car-stealing, protection rackets, bank robberies, and extortion from petro-states. Some states even use student funds for this purpose; between 1976 and 1978, Iraqi scholarships money to Palestinian students in Europe went through Abu Nidal, and he used his position to win such services from them as buying an apartment, renting a car, moving a suitcase, or sheltering a stranger.

Victims

The record shows that while the Syrian regime will exploit any locale, their targets remain almost always the same - Jordanians, Lebanese, Palestinians on the one hand, Israelis, Jews, Americans, and Britons on the other. (See the Table for a statistical summary of the 1983-86 period.) Jordanians have suffered far more from Syrian aggression than any other people. Jordan was also the site of the greatest number of incidents, followed closely by Greece and Italy. But neither Greeks and Italians were ever the intended victims. Contrarily, while only three incidents took place in Israel, Israelis and Jews suffered from nine attacks.

Arabs. Many of the Syrian regime's opponents are pursued abroad. Muhammad 'Umran, a prominent Syrian politician during the 1960s, lived in Tripoli, Lebanon from 1967; he was assassinated on 4 March 1972. Evidence at the scene indicated Syrian government complicity. Salah ad-Din al-Bitar, one of the founders of the Ba'th Party (which rules Syria and to which Asad belongs), founded a journal in Paris, Al-Ihya' al-'Arabi, in which he denounced the misdeeds of the Asad regime. Bitar believed that the "situation in Syria has reached the limit: each day, the dictatorship grows more bloody and the international policies of Hafiz al-Asad are an insult to the Arab cause." In July 1980, after calling on Syrians to overthrow Asad, Bitar was killed in a Parisian garage. Although the French government did not make formal charges for this crime, Syrian opposition groups fingered the military attaché of the Syrian embassy in Paris, Col. Nadim 'Umran, an 'Alawi.

Four days after Bitar's death, Asad announced that "all those who oppose the regime will be annihilated. . . . We will pursue them everywhere." In keeping with this threat, a leader of the Muslim Brethren, 'Isam 'Attar, was attacked by Syrian assassins in March 1981 in his house in Aachen, West Germany. He was not at home at the time and so survived, but his wife was killed. Other dissidents were killed by hit squads in West Germany, France, Yugoslavia, and Spain.

'Arafat's wing of the PLO has been attacked on a number of occasions. Either Abu Nidal or the PNSF assassinated a number of 'Arafat's men in Europe, including Na'im Khadir in Brussels, Majid Abu Sharar in Rome, and 'Isam Sartawi in Lisbon. A Palestinian with close ties to 'Arafat who edited an anti-Syrian weekly in Athens was shot three times from a yard away as he left his apartment building in September 1985. Two Palestinian groups based in Damascus claimed responsibility for the March 1986 assassination of Zafir al-Masri, the newly-appointed mayor of Nablus; in the West Bank itself, however, many residents accused Syrian operatives of the crime.

Lebanese leaders who resist Asad's wishes find themselves targeted by Asad. Kamal Junblatt, the Druze and leftist chief in Lebanon, was warned to silence his outspoken criticism of the Syrian military presence in Lebanon by the assassination of his sister in May 1976; he did not pay heed, so he too was killed ten months later. Fearful that Bashir Jumayyil would draw the Lebanese government too close to Israel, Damascus had the SSNP kill him in September 1982. In February 1988 security men found half a kilo of sophisticated explosives on a plane used by Bashir's brother Amin Jumayyil, the president of Lebanon. Immediately after the discovery, Syrian intelligence officers at the Beirut airport moved in, seized the explosive, and refused to let it go.

Lebanese journalists have also suffered Syrian violence. Salim al-Lawzi, publisher of the important Lebanese magazine Al-Hawadith, had acquired embarrassing information about internal conditions in Syria; in response, Syrian agents tortured and killed him in February 1980. A few months later, Riyad Taha, president of the Lebanese Publishers Association was gunned down from a car.

Nowhere, however, is the impact of terrorism so great as it is vis-à-vis the Jordanian government. The entire Syrian-Jordanian relationship is dominated by the threat of covert violence from Syria. One round of attacks began in late 1983: the Jordanian ambassador to India was shot on 25 October; the next day the ambassador to Italy was wounded; in Greece a security agent was killed in November; and in Spain on 29 December one embassy employee was killed and the other wounded by submachine gun fire. Abu Nidal's group - based then in the Rukn ad-Din quarter of Damascus - was implicated in all of these crimes.

The attacks then abated, only to begin anew when King al-Husayn and Yasir 'Arafat agreed on 11 February 1985 to work together, a pact strongly opposed by the Syrian and Soviet governments. Eleven days later, a four-month sequence of terrorism began. It included a bomb at the American Research Center in Amman; an explosion in an airliner of the Jordanian carrier, Alia; a hand grenade attack on Alia offices in Athens; a rocket attack on the Jordanian embassy in Rome; a rocket attack on an Alia plane in Athens; an Alia plane hijacked in Beirut and blown up; a bomb attack on Alia offices in Madrid; and the assassination in Turkey of a Jordanian diplomat who also happened to be the brother-in-law of the Jordanian commander-in-chief.

This campaign had Amman under siege. To end the assault, King al-Husayn in November 1985 wrote an astonishing letter to his prime minister. In it, he admitted that the Muslim Brethren who had been attacking the Asad regime had long been based in Jordan - something he had hitherto not realized! "I was deceived. . . . Suddenly the truth was revealed and we discerned what we had been ignorant of. We came to know that some of those who had something to do with what had taken place in Syria in terms of bloody acts were among us [in Jordan]." The camps were forthwith closed, Asad was appeased, a Syrian-Jordanian reunion came to pass, and Jordanians escaped Syrian terror. This orientation was confirmed in February 1986, when Husayn abrogated his accord with the PLO. The Jordanian example suggests one way for a target to shake the Syrian menace - surrender.

Non-Arabs. Of course, the Syrian regime targets Israelis and Westerners too. The French ambassador to Lebanon, Louis Delamare, was killed on 4 September 1981, less than a week after arranging a meeting between Yasir 'Arafat and the French foreign minister, Claude Cheysson. Although the French government - ever solicitous of Asad's feelings - did not directly charge Damascus with responsibility, it did leak information to Michel Honorin, a reporter for the TF1 television network. With this evidence, Honorin conclusively established Syrian complicity in a television program which aired on 21 April 1982. The very next morning, at 9:02 a.m., bombs went off at the offices of Al-Watan al-'Arabi, an Iraqi-backed weekly based in Paris. (It had also published embarrassing information on the February 1982 massacre at Hama.) By noon, the French government decided to expel the Syrian cultural and military attachés, Michel Kasuha and 'Ali Hasan (an 'Alawi).

Syrian operatives have repeatedly assaulted Americans in Lebanon. The U.S. ambassador, Francis E. Meloy Jr., was killed in June 1976 by Palestinians working for Syria. A Syrian intelligence officer, Lt. Col. Diyab, met with agents one or two days in advance to plan the 23 October 1983 destruction of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut. Among those in attendance were several members of Syrian-run Palestinian organizations, including Ahmad Hallaq and Billal Hasan from As-Sa'iqa and Ahmad Qudura from Abu Musa's group.

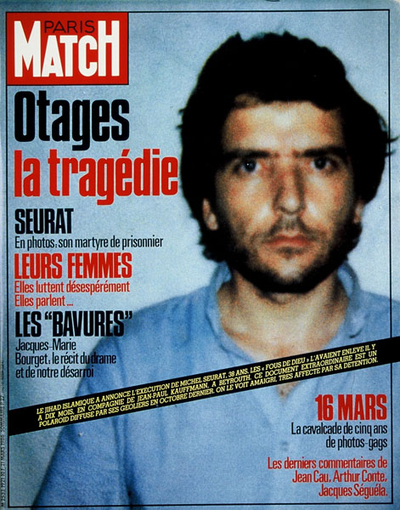

Asad took offense at the work of French scholar Michel Seurat (pen name: Gérard Michaud) and had him executed in March 1986. |

Arab Views on Syrian Terrorism

The Western democracies and Israel are not alone in holding Damascus responsible for terrorism; Arab governments also recognize Syria's role; sometimes they even discuss this topic publicly.

In the summer of 1985, Egyptian police discovered a car bomb placed outside the U.S. embassy in Cairo. Prime Minister Kamal Hasan 'Ali placed the blame on Palestinians working for Syria, and added that the incident took place with "the knowledge of the security service in Damascus." A year later, the interior minister accused the Syrians of planning "a number" of sabotage efforts in Egypt.

Kuwait experienced a rash of bombings because the government there refused to release the Lebanese who had blown up the U.S. Embassy. An investigation in September 1985 concluded that Syria was "directly responsible" for violence in Kuwait. Jordanian media came to a similar conclusion: "The fascist sectarian regime in Syria is not satisfied with the slaughter of Syrian citizens domestically . . . but is creating armed terrorist groups whose aims are . . . to carry out its terrorists acts outside Syria and throughout the Arab arena." They accuse Asad of setting up "special apparatuses for terrorism, assassination, and crime." Amin al-Jumayyil, the president of Lebanon, stated in 1988 that the Iranians would not have dared to take foreign hostages in Lebanon without Syrian approval.

Even leaders who themselves sponsor terrorism speak out against the Asad regime. Saddam Husayn, the Iraqi strongman, baldly declared that the Syrian and Libyan governments "encourage terrorism against Arabs." Yasir 'Arafat explicitly accused the Syrian police of killing Louis Delamare. The shooting in Amman of a former mayor of Hebron and current member of the PLO Executive Committee, Fahd al-Qawasima, prompted bitter comments from 'Arafat who, addressing the dead man at his burial, said: "The Zionists in the occupied territories tried to kill you, and when they failed, they deported you. However, the Arab Zionists represented by the rulers of Damascus thought this was insufficient, so you fell as a martyr." Salah Khalaf of the PLO stated publicly that Damascus was "behind recent communiqués" threatening the French government unless it released convicted terrorists from jail.

After the attack on Al-Watan al-'Arabi, the magazine's editor, Nabil al-Maghribi, commented: "It's an act of the Syrian [intelligence] services, and it's not the first time they have committed an outrage against the magazine. In December [1981], we defused a bomb at our door; the inquiry led to the cultural attaché at the Syrian embassy, Michel Kasuha." This incident prompted a PLO leader to observe, correctly, that Damascus had "evolved from local terrorism to international terrorism."

Finally, the citizens of Syria itself accuse their government of terrorism. Thus, a Muslim Brethren book is titled The Muslims of Syria and Nusayri Terrorism, while Sunnis refer to their government as the "'Alawi terror state."

Dealing with Damascus

State-Sponsored Terrorism. State-sponsored terror became a significant factor a few years after Asad came to power in November 1970, and the judicious use of this instrument has been a key instrument of state ever since. More than does any other government, the Syrian regime relies on secret warfare, more even than the three other major sponsors of terrorism in the Middle East: the PLO, Libya, and Iran. While the first two attract most attention, they in fact have a record of ineffectiveness. Despite nearly two decades of intensive terrorism, neither the PLO nor Libya has attained any of its goals. Iran and Syria have been engaged for shorter periods, but they have had much greater effect, for their rulers use terror not as a way to kill indiscriminately but as a means toward a specific end. They do not boast or indulge in media spectaculars, and they attend carefully to timing. Asad in particular acts with secrecy and pays close attention to his public reputation, not wanting to be seen as a sponsor of terrorism. His hallmark is the closely calculated, low key, and far-sighted use of terror. What makes this achievement especially impressive is having done all this without attracting the kind of opprobrium that attaches to the PLO, Libya, or Iran. There is an inverse proportion between extremism and efficacy. Qadhdhafi is the most extreme and least successful, and Asad the least extreme and most successful.

State-sponsored terrorism is the dominant form of terrorism today. The U.S. Department of State reports that "almost half the terrorist casualties suffered in 1983 were linked in a broad sense to state involvement in terrorism." According to a press report, the Quai d'Orsay concluded that every case of Middle East terrorism in West Europe has been "propped up" by Damascus, Tripoli, or Tehran.

The involvement of Syria and other states means that the old argument about injustice and political frustration lying at the source of the violence is now completely untenable. "In other words," Thomas L. Friedman observes, "the root causes of a significant portion of today's terrorism seem to lie not in any particular grievance that can be treated, but in the intrigues, power struggles, jealousies and machinations that are part of the web of international relations."

More specifically, the phenomenon will not go away with a resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict, for much of Syrian-backed terrorism does not bear on this conflict. Indeed, terrorism connected to Israel has been intended not to further a peaceful resolution but to block just such an eventuality. As soon as the Arab-Israeli peace process makes progress, Damascus goes into action. Asad does not protest the lack of progress in negotiations with Israel but seeks to block negotiations in the first place. The peace process must defy Syrian wishes. "Sadly," as Barry Rubin notes, "the more the United States pushes for peace, the more terrorism will increase."

Obstacles to a Policy. It is hard to see any role for the United Nations or other international organizations in confronting the problem of Syrian-sponsored terrorism. In the first place, problems with definitions constitute a major obstacle to international agreements or other clear-headed action. Some states hide behind the dispute over the existence of a phenomenon called terrorism ("a word with no meaning and no definition"). Others take refuge in the canard about one man's terrorist being another man's freedom fighter. These same considerations also explain why international organizations are unlikely to take legal action against state-sponsored terror. Further, voting coalitions entered into by the Syrian government in the General Assembly and many other bodies provide it with massive support. It can count on virtually automatic endorsement by all the Soviet client states and nearly all the Arab and Muslim states. Too, the Syrian government uses intimidation to get its way. The very willingness to use the terrorist instrument against enemies bespeaks a readiness to punish those who disregard Damascus' wishes; and many of those voting at the United Nations have enough problems without adding to these the danger of Syrian pugnacity.

Nor is there good reason to expect the West to take effective action against the Asad regime. Quite the contrary, the past decade shows that West European and North American governments are loath to confront Asad. Several factors explain this anomaly.

First, failing to understand the depth of Syrian-Soviet relations, they keep hoping that Asad can be wooed to the Western camp. Elias Sarkis, the president of Lebanon in 1970-76, succinctly captured the problem: "It's a real puzzler! Syria-U.S. relations make no sense to me. Here Syria acts as though it has a real conflict with the U.S., while the latter acts as though it has shared interests with Syria!" Some Americans seem to believe that Asad seeks good relations with the United States but is prevented from achieving them by American actions. "The Syrians would like to get out of their marriage to the Soviets." Western diplomats indulge in the hope that he can be convinced to renounce (as did Anwar as-Sadat) his connection to the Kremlin, if only the right deal and the right spokesman can convince him to take this step. They keep shuttling to Damascus in an effort to convince Asad to mend his ways, never seeming to understand that his calculus is different from theirs, and that the path he has pursued for two decades has brought him real benefits.

At the same time, Asad benefits by being perceived both as a close ally of the U.S.S.R and as being seduced away from the Soviets. Those who would contravene Asad knows that he can almost always count on his great power patron to support him.

Second, unlike the terror sponsored by Libya or the PLO, Syria's tends not to be directed against Western nationals. Rather than randomly attack Americans or Europeans, Asad pursues the more comprehensive goal of sabotaging U.S. policy in the Middle East. This makes him more of a menace but emotionally less of a target.

Third, the Syrian government is tough, strong, dangerous. The price for tangling with Asad is likely to be terrorism or more hostages taken in Beirut. And no one wishes to repeat the unsuccessful American confrontation with Syrian forces in late 1983. Even the Israelis think twice before tangling with Damascus.

Fourth, cries of indignation swell up in Damascus whenever foreign governments (including the West German, Italian, British, and American) point to Damascus as a major sponsor of terrorism. With one voice, President Hafiz al-Asad and his aides reply that they are the victims, not the perpetrators of terror. They even claim that they bear no more responsibility for terror than do the Italian authorities for the Red Brigades. In support of this, the brother of the president dismissed terrorism as "cowardly, disgusting, and revolting." Vice President 'Abd al-Halim Khaddam declared that "Syria is the country that is most hit by acts of terrorism." Defense Minister Mustafa Tallas called Syria "the first victim of terrorism." The information minister declared that "We do not maintain any relations with groups such as that of Abu Nidal." Syrian radio echoed: "Syria is among the countries that has condemned, denounced, and resisted terrorism."

Fifth, the Syrians have been singularly successful at getting the credit for uncovering and returning hostages that their own proxies and allies captured in the first place. Gérard Michaud explains how this is done: "The victim disappears without the authors of the kidnapping claiming responsibility for their act or identifying themselves; then the victim reappears one happy hour - like a white rabbit produced from the hat of the Syrian information service." Western officials often travel to Damascus to seek Asad's aid in reducing terrorism. In one case, Spanish authorities passed on to the Syrians copies of the "false but genuine" Syrian passports belonging to the two culprits in an attack at Madrid airport! Another example: David Dodge, former acting president of the American University of Beirut, was kidnapped in Lebanon but spent part of his captivity in Iran. To get from one state to the other he had to be taken through Syria - which could only be done with Damascus' permission. After his release by the Syrian authorities, the White House expressed "gratitude" to Hafiz al-Asad and his brother Rif'at for their "humanitarian" efforts. Almost identical tributes were repeated in early 1990, when two Robert Pohill and Frank Reed achieved their freedom via Damascus.

This approach had particular importance in 1987, when Damascus made special efforts to improve relations with the states of Western Europe. In January, the sequence of events went like this: two Germans were captured in Beirut, Bonn sent a special envoy to Damascus to discuss their plight, the German government decided to restore full diplomatic relations with Syria, and soon after the two Syrian government announced that its exertions had succeeded in winning the Germans' release. Several months later, an almost identical sequence of events culminated in the release of French hostages. The return of the American ambassador was related to Syrian efforts to release an American captive, Charles Glass. Minister of Defense Mustafa Tallas himself offered a similar deal to London (Terry Waite in return for diplomatic relations), but the Thatcher government turned him down.

Finally, efforts to leave no "return address" have worked, for although everyone knows that the Syrians are deeply complicit in terrorism, with few exceptions, states try to avoid the clear fact of Syrian government complicity. Suspicions abound, but time and again governments shy away from directly blaming Damascus. Thus, in May 1986, at the height of Syrian activities, the White House spokesman called in "premature" to judge Syrian complicity in terrorism, saying the evidence was not "conclusive." Even though the Italian minister of the interior acknowledged having documents "proving that Syria is not innocent," an Italian magistrate ignored highly incriminating circumstantial evidence of an official Syrian role in the December 1985 Rome airport massacre; his reluctance to issue a warrant was explained on the basis of insufficient evidence to make a case in court. Off-the-record, French officials in 1986 called Syrian responsibility "virtually a certainty," but they did not say so in public.

For all these reasons, the Syrians have repeatedly managed not to pay the full consequences for their actions.

The first priority in developing a policy is to understand the nature of the Syrian regime, its behavior in domestic and foreign affairs, and its key role in so many of the Middle East's problems. The true dimensions of the problem need to be established before efforts are expended on devising a policy toward the Syrian regime. The Syrian-Soviet relationship is not a marriage of convenience; the Syrian state is a formidable opponent of U.S. and Western interests; Asad does not accept Israel's existence and does not want a resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict; and he threatens several governments friendly to the United States. Contrary to American assumptions, the Syrian government would not benefit from peace.

Only when these basic points have been accepted and become the premises of Western policy toward Syria is it useful to formulate the specifics of a response.

Formulating an American Policy

For the sake of argument, let us suppose that these points are accepted. What then? Formulating policy toward Syrian-backed terrorism begins by keeping in mind that this is an instrument of state and a form of warfare. Accordingly, efforts to reduce its incidence must go beyond police measures and incorporate political and military steps. Really to be effective, American efforts must consider the regime as a whole, not just its reliance on secret warfare. Accordingly, the formulation of American policy toward Syrian-backed terror is almost identical to a policy toward Syria.

It is futile for the United States to expect that modest pressures or small inducements can reduce Syrian terrorism, much less that he can be convinced that using this instrument goes against his interests. Trying to intimidate Asad by buzzing him with a few fighter planes (as happened in late 1983) was as misconceived as winning his favor with a State Department statement that Damascus is a "helpful player" in Lebanon (as happened in July 1984). Rather, to influence Syrian policy requires a steady hand and a willingness to endure setbacks.

The U.S. government has a variety of options. The list that follows goes from the least ambitious steps to the most:

- Wait out Hafiz al-Asad. Failing anything more resolute, American policy can simply hold out until Asad dies. This should not take too long, for Asad, born in 1930, is a sick man. In November 1983 he had a heart attack and came close to dying. He is also a diabetic. The outward signs of his ill health are obvious even to the untutored eye: rapidly grayed hair, sallow skin, and a perpetually-drawn look. Asad's health matters enormously for the future of Syria for he is a brilliant tactician who single-handedly keeps the state's whole juggling act in the air. When Asad dies, an internecine battle to succeed him is almost sure to follow. The improbable power that Asad has amassed over two decades is almost certain to be dissipated in the course of this struggle.

- Change the tenor of U.S.-Syrian relations. Decry Syrian practices in human rights assemblies; point to Damascus as a major source of troubles in the Middle East; publicize charges of Syrian-sponsored terrorism. This means an end to such statements as that of former Assistant Secretary of State Richard Murphy that "Syria has too much to gain from and has an important role in achieving a lasting piece in the region." It also means reducing the size of the Syrian missions in Washington and at the United Nations.

It should not be so hard to call a spade a spade; and there is precedent for this. When he was vice-president, George Bush announced that the U.S. government is "convinced that their [Syria's] fingerprints have been on international terrorist acts." Even the State Department made strong statements, asserting that court findings in London and West Berlin indicated "a pattern of direct involvement by senior Syrian government officials."

- Pressure third parties to alter their relations with Damascus. (1) Allies should reduce the size and number of Syrian diplomatic missions abroad. Deprived of diplomats and missions, Damascus loses its main conduit for arms, funds, and intelligence to foreign locations. (2) The Kremlin should limit the flow of arms to its Damascene client and restrain Asad's bellicosity. (As Soviet relations with Syria provides one of the key tests of Mikhail Gorbachev's policies, this has an importance that transcends Syria.) (3) The Arab states should keep the focus on getting Syrian forces out of Lebanon. Those forces today control two-thirds of the country and their presence in Lebanon serves three main purposes for Asad: it shows he has achieved something toward the Greater Syria dream; it offers a controlled anarchy in which terror bases and training take place without the Syrian government having to take responsibility; and it is the source of the drugs which provides his government with billions of dollars. The Arab states have shown their eagerness to end the Syrian occupation; discreet backing from the U.S. government can help this cause.

- Impose economic sanctions. A number of pressing problems have emerged in Syria in recent years. The country's economic situation deteriorated as oil revenues declined, military expenditures increased, and the country has been mired in Soviet-style inefficiency. Electric power is routinely cut in the cities for hours at a time. On occasion, foreign currency reserves have been reduced to 20 days' worth. Even Syrian agents on the Golan Heights have seen their pay cut from one-third to one-half of its former levels. To deal with these problems, Asad has often called for economic sacrifices:

We suffer from economic problems. We all feel them. . . . We must move from the phase of economic imbalance to the phase of equilibrium and from the phase of overconsumption and excessive imports to meet our needs to the phase of rationalized consumption. . . . Self-reliance calls for increasing production and reducing consumption. . . . Reduced consumption may displease many of us.

In the end, however, Asad is afraid to demand too much of the Syrian population; tax rates remain remarkably low and the main burden of the $4 billion or so spent on the military over the past decade falls on foreign allies, mainly the Soviet Union and the Arab oil-exporters.Asad's predicament offers real opportunities for pressuring the Syrian regime to change its behavior. Patrick Clawson concludes from his path-breaking study of the Syrian economy that "contrary to conventional wisdom, Syria is vulnerable to outside pressure. . . . The vulnerability is economic, because Syria's economy is extraordinarily dependent on the Soviet Union and the oil-rich Arab states." Those states can exert a significant leverage over Syrian policy; taming Syria can be made a test of Mikhail Gorbachev's sincerity as well as Saudi Arabian and Kuwaiti friendship.

- Undertake military action. The American raid on Libya in April 1986 is the one major case of military retaliation for a terrorist incident. It is worth noting for this reason, and because of the deep irony it contained. The U.S. government had to resort to military action because its allies would not take the diplomatic, commercial, and political steps which might isolate Mu'ammar al-Qadhdhafi and squeeze his regime. The bombing itself seemed to be a highly unpopular step in Europe and Japan. Yet its effect on the Western allies was highly salutary. "U.S. military action had a central role in galvanizing the allies to adopt positions that were markedly closer to those of the United Nations." One sign of this shift came a month later, at the Tokyo economic summit meeting, when the U.S. and six principal allies declared their "condemnation of terrorism in all its forms" and pledged to fight terrorism through "determined, tenacious, discreet, and patient action combining national measures with international cooperation."

The implications seems to be that disarray among allies leads to American military action; which leads to a coordinated stand by the Western governments. Applying this to Syria, it suggests that, however risky, military action may once again bring the allies closer together.

Table: Intended Victims and Locations of Syrian Terror, 1983-86

The following statistics about 49 cases of Syrian terrorism derive from a U.S. government report, "Syrian Support for International Terrorism: 1983-86." Being an official review, this document errs on the conservative side. For example, it ascribes none of the PKK activities to Syrian sponsorship.

| Identity of Intended Victims | |

| 18 | Jordanians |

| 9 | Israelis & Jews |

| 8 | Americans |

| 7 | 'Arafat's PLO |

| 6 | Britons |

| 1 | Kuwaitis |

| Summary | |

| 26 | Arab |

| 23 | Western & Israeli |

| Locations | |

| 11 | Jordan |

| 8 | Greece |

| 7 | Italy |

| 4 | Turkey |

| 0 | Cyprus |

| 3 | Spain |

| 0 | Israel |

| 1 | West Germany |

| 0 | United Kingdom |

| 0 | Austria |

| 0 | Netherlands |

| 0 | Portugal |

| 0 | Romania |

| 0 | Kuwait |

| 0 | U.A.E. |

| 0 | India |

| Summary | |

| 23 | Western Europe |

| 13 | Arab Middle East |

| 11 | Non-Arab Middle East |

| 1 | Eastern Europe |

| 1 | India |

Oct. 13, 2004 update: For news on the case described above, see "Nezar Hindawi's Attempt to Blow up an El Al Airplane."