The murder trial of the year begins today in Atlanta.

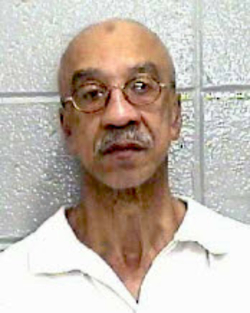

Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin. |

To avoid arrest, Al-Amin flashed a fake police badge from a small town in Alabama. The ruse worked, and he was let off - but not for long. The police soon figured out the fraud and he was indicted and assigned a court date.

When Al-Amin failed to appear at his hearing, the judge issued a bench warrant for his arrest. On the evening of March 16, 2000, two sheriff's deputies (themselves both African-Americans), Aldranon English, 28, and Ricky Kinchen, 35, tried to serve the warrant. The young officers were cautioned about "Aggravated assault, possibly armed," but that's all they knew about their suspect.

They had no idea of that they were pursuing a black nationalist once known as H. Rap Brown - whose history of violence goes back to before they were born. They didn't know he claimed "rap" music was named after him, nor that his 1960s antics earned him the reputation as "the violent left's least-thoughtful firebrand."

They didn't know he incited a mob to torch two city blocks in Cambridge, Md. ("It's time for Cambridge to explode, baby") in 1967; nor that he was "minister of justice" for the Black Panther Party in 1968; nor that he was listed on the FBI's "Most Wanted" list in 1970; nor that he attempted to rob a New York City bar and injured two police officers in 1971; nor that he spent 1971-76 in New York prisons.

The officers didn't know that after converting to Islam, leaving jail and moving to Atlanta, Al-Amin continued his career of violence - illegally carrying a pistol, organizing a gang for violent crimes and heading a mosque whose members received paramilitary training.

Unaware of all this, when the two deputies found Al-Amin standing by a parked car with his hands concealed, they routinely ordered to show his hands. "OK, here they are," he replied - and allegedly pulled out two guns and fired at them, seriously wounding English and killing Kinchen.

Al-Amin fled to Alabama and, for the second time in his life, made the FBI's most-wanted list. Four days later, he was caught along with his car (with a tell-tale bullet hole) and guns (which ballistic tests proved to be those used to shoot English and Kinchen).

The Fulton County district attorney announced that the state would seek the death penalty for Al-Amin. Al-Amin declared himself not guilty.

The trial's sensationalism results from Al-Amin's 1960s fame, but its significance lies in his current Islamic connections.

His Islam is - not surprisingly - the militant kind, hating America in the spirit of Osama bin Laden. In Al-Amin's view, the United States and Islam are opposites: "When we begin to look critically at the Constitution of the United States," he wrote in 1994, "we see that in its main essence it is diametrically opposed to what Allah has commanded." He spells his country "amerikkka" and chastises American blacks for integrating into their country's life: "The problem with African-Americans is that they are so American."

One might think that, given his criminal record and wild-eyed views, Al-Amin would be shunned by the Islamic establishment in America. Wrong: Led by the Council on American-Islamic Relations, they have lauded his leadership, sought him out as a speaker and acclaimed his writings.

Those same institutions rallied to his defense after his arrest for killing the policeman. Mosques, college groups, mosque leaders and others proclaimed Al-Amin's innocence, collected signatures for his release and raised money for his defense. They declared the murder charges "especially troubling" because such behavior would be so "out of character."

Incredibly, rather than condemn Al-Amin's 35-year history of ideological extremism, political violence and personal criminality, the Islamic organizations praised his "moral character." Rather than collect money to help pay educational expenses for Officer Kinchen's two young, fatherless daughters, they raised money for Al-Amin's legal defense fund.

Sadly, it looks like Jamil Al-Amin has turned into the Muslim version of O.J. Simpson. His admirers seem to care much less about justice than about his vindication.

Jan. 7, 2002 addendum: For a fuller analysis of this topic, see "The Curious Case of Jamil Al-Amin."

March 9, 2002 update: See "Jamil Al-Amin Goes to Jail" for news on Al-Amin's conviction and further developments.