It is relatively simple to study the impact of modernity on Middle East aristocrats (for they came in contact with Europeans) and on intellectuals (who wrote books), but what about the mass of the population? Ethnographic studies provide important information, as do government surveys. But comprehending the ways in which individuals thought, felt, and acted is almost impossible to glean from such sources.

Book cover of "Bayn al-Qasrayn." |

Family relations

True to a long-standing Muslim pattern, the father, Ahmad, completely dominates the lives of his wife, two daughters, and three sons. He not only has absolute jurisdiction over the family, but he routinely demands acts of servility of them: the children must kiss his hands when he is angry with them; his wife, Amina, sits by his feet each night when he returns home from his philandering to take off his shoes and socks (p. 13). The family is so fearful of Ahmad that none of them can lie to him, even if they plan to do so in advance (p. 22); at best they procrastinate briefly (p. 351) or cry (p. 487). Yasin, the eldest son, one time witnesses his father involved with a mistress but he cannot exploit this knowledge, unable even to use it in self-defense when himself caught with a woman (pp. 323, 362, 444). While members of the family sense Ahmad's power, regardless of his distance (p. 189), Ahmad himself freely indulges in infidelities without concern for Amina's awareness of sensibilities. He is not accountable, yet maintains full control over everyone else.

While Ahmad's authority overwhelms his relations with wife and children, it also compels them to ally with each other. The whole family, including the mother and the ten-year-old child, fear Ahmad in like manner; a common sympathy arises and sustains them, a sympathy that is renewed daily when the whole family but Ahmad drinks coffee together in the afternoon (pp. 61, etc.), deriving deep relief from the common bonds forged living under Ahmad's dominion. Despite very different personalities and activities of the individual members, they share a wide range of hopes and fears.

According to Mahfuz, then, the traditional Muslim family structure still stands firmly in Cairo at the time of the First World War. Yet, signs of impending changes are clear: when Fahmi, the second son, refuses to comply with Ahmad's order to stop his nationalistic activities (p. 487), he acts as a modern son. Fahmi is not merely disobedient; he is inspired by moral principles that Ahmad can neither share nor overrule through the force of personal authority. Such a conflict between generations was almost inconceivable in the more static society of earlier periods, when both father and son would have been similarly attuned to the traditional loyalties. Nationalism, then, stimulates the first major defiance of Ahmad's authority; once the precedent has been set, repetitions will no doubt recur with increasing frequency and diminishing justification. As Ahmad's power diminishes, family relations are on their way towards modernity.

Sexual attitudes

Relations between the sexes make up a major portion of Bayn al-Qasrayn. Three aspects of this problem receive particular emphasis: the inferiority of women, the "double-standard," and the seclusion of women. Amina embodies the characteristics of a traditional woman, while Yasin's wife, Zaynab, represents the new breed.

In the view of traditional Muslims, women are inferior to men. Ahmad sums up this view when he tells Amina "you are nothing but a woman and all women are mentally deficient" (p. 179). Amina does not argue the point; she has always heard that she is inferior and she believes so, as the obedience she pays Ahmad shows very clearly. Once, in the first year of their marriage, Amina expressed displeasure at Ahmad's nightly outings and he replied "I am a man. The matter is settled; I will not accept any comments on my behavior. You must obey me and take care not to compel me to discipline you." Amina then "learned from this and the other lessons that followed it to endure everything - even the presence of goblins - in order not arouse his anger. She was supposed to be obedient without restriction or condition; and she was" (p. 9). In another passage, Yasin tells Zaynab "about men's absolute right to do as they wish and women's duty to obey" (p. 382).

Women living in traditional Egypt accepted the right of men to lead separate night lives. While the wife stays at home, many husbands (among those who can afford it) go out every evening. They sit in cafes, attend musical performances, and often end up with whores or mistresses. The husband might not return until dawn, but no matter when he does come home, the wife awaits him and the two of them retire together (pp. 1-18). One time, when Amina wonders where her husband goes at night, she is informed that a man like Ahmad "with his continuous nightly amusements cannot live without women" (p. 10). At the same time, Amina's mother reminds her that Ahmad "married you after divorcing his first wife; it is in his power to reclaim her if he wishes, or to marry a second, third, or fourth wife ... so thank God that you are still an only wife" (p. 10).

Husbands with the means to pay for servants and a private bath usually forbade their wives to leave the home; secluding women indoors assured their fidelity. For a woman this could mean not leaving the house from the moment she married; in twenty-five years Amina stepped outdoors only to visit her mother on rare occasions, and even then was chaperoned by her husband. As Yasin told Zaynab, "since time immemorial, the home is the domain of women, the world that of men" (p. 382). On another occasion, Yasin reflects on how women "are domestic animals and should be treated as such. They should not be allowed to intrude in our private lives, but should wait at home until we are finished with our amusement" (p. 388).

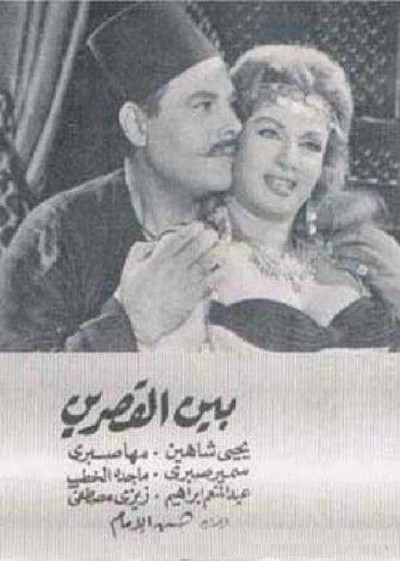

Poster of the 1964 movie of "Bayn al-Qasrayn." |

Zaynab, the daughter of an Turko-Egyptian friend of Ahmad's and briefly Yasin's wife, wants to change her position as a woman. She enjoyed unusual freedom in her youth, even going to the movies on occasion with her father (p. 360), and this deeply affected her subsequent development. One day, not long after Zaynab married Yasin, she offers to accompany him on his nightly outing. Yasin accepts and they spend the evening out together. On hearing is this, the rest of the family is shocked - and no one more so than Amina or her elder daughter Khadija. The two of them discuss Zaynab's audacity, Khadija remarking that Yasin "has perfect right to love the night clubs that he enjoys so much or to remain out until dawn, if he wishes, but the idea of his wife accompanying him could not have been his own" because it is not traditionally acceptable (p. 355). Khadija accurately perceives that it was Zaynab, with her modern ideas, who instigated the episode.

But Zaynab's rebellion against seclusion is of minor importance compared with her refusal to recognize the male prerogative to a double standard, the day she discovers Yasin in the room of her own black servant girl and, stunned by this blatant infidelity, Zaynab retreats to her father's house and demands a divorce. Zaynab's mother advises her against this, reminding her that "all men go out for nightly entertainment and they also drink - including her father, though his home was always filled with virtue. He always returned home, no matter what the entertainment, no matter how drunk" (p. 442). Amina has, of course, no sympathy for Zaynab, but is shocked by her presumption: "How can she claim for herself rights which belong to no woman?" (p. 448). As for the men, both Ahmad and Zaynab's father are more incensed by the object of Yasin's infidelity (an elderly servant) than by the act as such (p. 446). Had Yasin chosen a more desirable woman, they would not even have seriously considered Zaynab's insistence on divorce.

Just as Fahmi introduces the first modern element into family relations, so Zaynab brings it to sexual relations. She is alone in her attempt to achieve a different sort of life, the other women opposing her even more than the men. Like Fahmi, Zaynab gets her way, however; Yasin divorces her and she is released from an intolerable marriage.

Politics

The question of changing political allegiances dominates the last third of Bayn al-Qasrayn. The year is 1919. A peace truce is announced (p. 365) and the Wafd Party emerges with Sa'd Zaghlul as leader (pp. 368f). As the year unfolds, the 'Abd al-Jawad family reacts to Zaghlul's repeated attempts to go to Britain, his exile to Malta (p. 402), the military occupation of Cairo (p. 422), Zaghlul's release from Malta (p. 553), and the ensuing celebrations (pp. 565f). These political events strike strong and desperate responses among the members of the family. The extremes range from Amina who believes that the long dead Queen Victoria should be politely asked to release Zaghlul (p. 373) to Fahmi who is eager to lay down his life for Egyptian independence (p. 488). In the intermediate positions, Yasin takes interest in politics (pp. 374, 398) and Ahmad signs a nationalist petition. (pp. 377)

"A view of the Sharia al-Muizz il-Din Allah, near Bayn al-Qasrayn, Cairo," 1886, by Girolamo Gianni (1837–1895). |

While the behavior of aristocrats and the books of intellectuals do not reflect the general manners and mentality of Egypt at the time of World War I, it was those two groups who stimulated the family, sexual, and political changes outline above by responding to European stimuli. They in turn influenced the baladi (non-elite, common) class in Egypt. The 'Abd al-Jawads were at the top of the baladi hierarchy: Ahmad was successful merchant, one son married the daughter of a Turko-Egyptian line, and another went to law school. Mahfuz implies that, just as aristocrats and intellectuals functioned as intermediaries of modern culture between Europeans and the baladi classes, so families such as the 'Abd al-Jawad first picked up modern influences and transmitted them to poorer folk. This process still continues; one finds even today the lowest classes of Egypt (urban poor, peasants) only marginally affected by modernization.

Bayn al-Qasrayn portrays Egypt at the moment when the baladi classes are initially affected by modernization in vital ways. Family relations are first influenced when new circumstances lead to a decrease in the authority of the pater familias. Sexual attitudes and the position of women both undergo disruption when Egyptian women demand more equality. Nationalistic fervor overtakes allegiance to the umma. The old ways of life continue at the time of World War I, but several crucial elements of modernity have begun to wreck traditional structures.

Foreign Policy Research Institute

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Aug. 30, 2006 update: Mahfouz died today, age 94 years.