I have asked many people in position—in England and elsewhere—why England has capitulated to the Zionists, and none of them has been able to give me a straight answer. It is not money. But what is it?

- A British general serving in Palestine (1920)[1]

The myth of Jewish power and world conspiracy in most cases wreaked destruction on Jews—but not always. Curiously, it also had some positive consequences for them. In these incidences, fear of Jews led antisemites to treat Jews with a caution that redounded to the latter's benefit. Notable cases include the British decision to issue the Balfour Declaration in 1917, various Arab leaders' interest in winning Great Power favor, Stalin's support for the nascent Israel, and the confused Japanese treatment of Jews during World War II.[2]

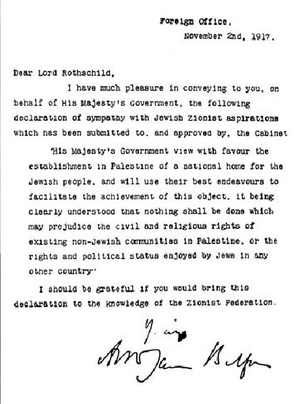

The Balfour Declaration

From its inception, Zionism has won the backhanded support of antisemites, who saw in it a means to reduce or even remove Jews from their presence. In 1878, a prominent Hungarian antisemite urged Jews to take power in the distant expanses of the East: "now is time for a people as progressive, educated, and great intellectual competence as the Jewish to take a leadership role in the Orient." He then called on Jews "to realize the regeneration of the Muhammadan empire."[3] A German counterpart went further, admonishing the Jews, "Conquer Asia, your homeland, like you conquered us."[4]

The same ideas recurred all over the world. Katsuisa Sakai, a Christian minister, published three Protocols-inspired tracts in 1924, warning Japanese that the Jewish conspiracy would soon extend to Japan "and even encroach on the Imperial family itself."[5] At the same time, Sakai enthusiastically supported Jewish nationalism: "The rebuilding of Zion is not merely the ambition of the Jews but a mission from God. Their movement is thus not an invasion but a revival. They should attack proudly, their flag unfurled!"[6] So stalwart a Zionist did Sakai consider himself that he used this credential to petition (without success) for a loan from a Zionist organization in England.

British overestimation of Jewish power in the United States and Russia had a central role in the decision to issue the Balfour Declaration in November 1917. The story begins in July 1908, when the Young Turks (formally, the Committee of Union and Progress) took effective power in the Ottoman Empire. Although the Young Turks consisted primarily of Turkish-speaking, Muslim military officers, the British ambassador in Istanbul, Gerard Lowther, saw them as mainly Jewish in inspiration and leadership. This overestimation of Jewish power struck many Europeans as plausible and was widely accepted (some added a Masonic influence). In antisemitic eyes, then, Jews controlled one great power leading up to and during World War I.

This event did much to strengthen belief in Jewish power. As early as 1910, Ambassador Lowther raised the prospect of Zionists' helping the German government of Kaiser Wilhelm II to achieve its expansionist goals. When the world war came four years later, the Germans did indeed try to win the Zionists' favor, for Berlin also overestimated their power and thought that by winning Jewish favor they could influence a group of key Americans. Specifically, the Germans intervened with their Ottoman ally to reduce his hostility to the Zionists in Palestine and provided many other services (including German diplomatic travel documents made available to a Zionist leader).

But all this was merely preliminary skirmishing. By 1915, stalemate had descended on the Western Front, with British (as well as French and Germans) soldiers going off to their deaths by the hundreds of thousands, and to no avail. To extricate themselves from this impasse, diplomats in London desperately sought new allies, including both Zionists and Arabs. The Arabs' location and numbers gave them obvious leverage. The case of the Jews is more subtle and reflects the prevailing overestimation of their power. To win Jewish favor, David Lloyd George (the future prime minister) as early as 1915 looked favorably on a Zionist state in Palestine. A Foreign Office cable dated 11 March 1916 suggested that the side that favored Jewish settlement in Palestine might appeal "to a large and powerful section of the Jewish community throughout the world." This being the case, "the Zionist idea has the most far-reaching political possibilities." Were the Entente Powers to support Zionism, the author raised the danger that they would win to their cause "the Jewish forces in America, the East and elsewhere."[7] Were the British to preempt, they could benefit from these same forces.

The Balfour Declaration. |

This awe of Jewish power had an importance that far transcended the politics of the moment, leading as it did to the Balfour Declaration in November 1917, a statement that announced the British government's favoring "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." Foreign Secretary Balfour argued (during the War Cabinet meeting at which the declaration was adopted) that its passage would allow the British government "to carry on extremely useful propaganda both in Russia and America."[9] Other observers took this idea to extremes. Noting that Lenin seized power just five days after the Balfour Declaration was issued, one member of the Intelligence Directorate at the War Office speculated that "it is even possible that, had the Declaration come sooner, the course of the [Russian] Revolution might have been affected."[10]

These exaggerated visions of Jewish power had the effect of placing the British Empire on the side of Zionism, however fleetingly, and thereby enormously boosting the Jewish national movement at a critical moment.

Arab Friendliness to Israel

Weizmann and Faysal. |

Apparently, he believed that the Zionists, in addition to representing a potential economic asset to Syria, possessed great influence with the world's major power, Great Britain (from whom they had already gained the Balfour Declaration). Since the Zionist movement also carried some weight in the United States (which was involved in the post-war peace conference), it could, in Faysal's thinking, help him achieve his grand aim, namely, Arab independence under his leadership, backed by Britain and recognized by the international community. To realize this goal and to nullify France's claim to control Syria, Faysal conditionally agreed to the creation of the Jewish national home in Palestine.[11]

Note the progression here: first the British issued the Balfour Declaration, believing Jews to be influential in the United States; a year later, an Arab king reached an agreement with the Zionists in good part because the Balfour Declaration showed Jewish influence over London!

Nearly twenty years later, Syrian and Lebanese leaders met with Chaim Weizmann and other Zionists, again as a way to curry favor. This time they did so with an eye not to London but to Paris, where the Jewish and pro-Zionist Léon Blum had become prime minister in June 1936. Weizmann reported that Syria's Prime Minister Jamil Mardam had offered "to tell the Arabs in Palestine to lay off, if we would help them in Syria; the assumption being, apparently, that we had Blum in our pockets."[12] Likewise, an Israeli source reported that the Sunni leader (and later independent Lebanon's first prime minister) Riyad as-Sulh was prepared, "if Syria achieved independence," to "do all that was possible to try and ease the situation in Palestine," in return for Jewish economic and organizational assistance.[13]

In recent years, Israel's reputed clout in Washington has won it the amity of weak states around the world interested in improving relations with the U.S. government, to the point that Israeli leaders sent word to their embassies to cut down on the influx of high-level visitors. More remarkably, operating on the basis of an inflated idea of Israel's utility as a door to the United States, anti-Zionist states seek Israel out. Iran accepted the Israeli initiative that led to the Iran/Contra scandal for this reason; then Iraq and Libya initiated diplomatic contacts with Israel. This led to an odd situation in which the U.S. government rapped Israel's knuckles for contacts with Arab states. In August 1993, it reportedly delivered a "stern" warning to Jerusalem "to stop its efforts to establish contacts with Libya."[14] A year later, Washington admonished Jerusalem for its diplomacy with Iraq. Reviewing these strange developments, the Israeli commentator Yo'el Marcus concluded that these Arab leaders have a "mystical belief . . . in the veracity of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. . . . Never has such a groundless anti-Semitic document done us [Israelis] such service as this document. . . . Small wonder that it is difficult to walk around in this country without bumping into some minister, prince, king, prime minister, et al., who are visiting us with an unconcealed hope that we open doors for them in America."[15]

Soviet Union

Soviet support for Zionism in 1947-48 had a very different quality: not to win the favor of a great power but to harm its interests. Faced with London's efforts to exclude the Soviet Union from the Middle East, Stalin reacted by seeking out and supporting the most powerful force in the area in the hopes of turning it into an anti-imperialist ally. He and his aides did not see the Arab leaders filling this role, having deemed them as nothing but weaklings and lackeys of the imperialist powers. In the colorful wording of one Soviet official, "There will be revolutionary developments in the Hawaiian Islands before anything will move in the Arab East."[16] In contrast, Stalin apparently believed in a Jewish power so vast that, in league with the British, it would overwhelm Soviet efforts. To prevent this, he did his best to separate the Zionists from London. And so, for one year's duration, the Soviet Union became the prime supporter of Zionist aspirations to found a sovereign Jewish state, forwarding its cause diplomatically and militarily at its moment of supreme need.

Thus was the establishment of the state of Israel, from the Balfour Declaration to its war of independence, helped by the strange phenomenon of benign antisemitism.

Japan

Benign and malign views of Jewish power have co-existed in Japan for nearly a century, leading to confusion so intense it has a near-comic quality. Curiously, both originated in war against Russia. The benign view began when some Jews (notably Jacob Schiff) won financial assistance for Japan in its war of 1904-05 against Russia. The Russians responded to that loss by resorting to a Jewish conspiracy. It was precisely that malign view that they imparted to Japan in 1918-22, as White Russians fought alongside Japanese troops in Siberia. The anti-Bolsheviks widely accepted the Protocols of the Elders of Zion as the explanation for the Russian Revolution and convinced their Japanese contacts of its truth.

Profoundly ignorant about Jews but fascinated by this reputedly powerful force and convinced of the reality of a Jewish conspiracy, the leaders of fascist Japan wavered between hostility and friendliness (appealing to Jews, "you should actively support and contribute to the Holy War of Sacred Japan").[17] To win Jewish goodwill, they invited Jews in the late 1930s to settle in the occupied territory of Manchuria, hoping this gesture would inspire the Elders of Zion to use their influence to improve American opinion toward Japanese imperialism.

These contrary views came to a head at a December 1938 cabinet meeting. Hours of debate on the Jewish issue kept the cabinet in session deep into the night, with one side arguing for the malign view coming out of Nazi Germany and the other for the benign view that had some strength in Japan. Advocates of the benign view recalled the war of 1904-05 and hoped in the future for more financial and political help (e.g., to make President Roosevelt look on Japan more kindly). In the end, the latter won ("We cannot afford to alienate the Jews"): Jews would be allowed into Japanese-occupied Manchuria so that they would develop the area and bring favorable publicity to Japan. In deference to Nazi Germany, however, this policy was not publicly declared.[18]

[1] Quoted in C. R. Ashbee, A Palestine Notebook, 1918-1923 (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page, 1923), pp. 90-91.

[2] Earlier instances along these lines did not include fear of a Jewish world conspiracy, and so are not included here. One example dates from 1807, when Napoleon convened a "Great Sanhedrin" with an eye to giving European Jews a central authority, and thereby winning their favor; in return, he hoped that Jewish businessmen would join his cause and help with the blockade of Great Britain. Poliakov 3.228

[3] Gyözö Istóczy, speech to the Hungarian parliament, 25 June 1878. Text in W. Marr, Vom jüdischen Kriesschauplatz: Eine Streitschrift (Bern: Rudolph Costenoble, 1879), p. 43. Did Istóczy influence eighteen-year-old Theodor Herzl, then a student in Budapest? Moshe Zimmerman raises this possibility in Wilhelm Marr: The Patriarch of Anti-Semitism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 87.

[4] Marr, Vom jüdischen Kriesschauplatz, p. 39.

[5] Quoted in David G. Goodman and Masanori Miyazawa, Jews in the Japanese Mind: The History and Uses of a Cultural Stereotype (New York: Free Press, 1995), p. 82.

[6] Ibid., pp. 82-83.

[7] Foreign Office to St. Petersburg, 11 March 1916. Quoted in Elie Kedourie, Arabic Political Memoirs and Other Studies (London: Frank Cass, 1974), p. 238.

[8] Mark Sykes to George Arthur, 18 March 1916. Text in ibid., pp. 240-41.

[9] Quoted in Leonard Stein, The Balfour Declaration (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961), p. 547.

[10] Quoted in ibid., p. 348.

[11] Moshe Ma'oz, Syria and Israel: From War to Peace-making (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), p. 4.

[12] Quoted in Neil Caplan, Futile Diplomacy, vol. 2, Arab-Zionist Negotiations and the End of the Mandate (London: Frank Cass, 1986), p. 49.

[13] Quoted in ibid.

[14] Israel Television, 25 August 1993.

[15]. Ha'aretz, 16 August 1995.

[16] Said in the late 1920s; quoted in Oded Eran and Jerome E. Singer, "Soviet Policy towards the Arab World, 1955-71," Survey, Autumn 1971, p. 10, n. 2.

[17] Koreshige Inuzuka, an "officially recognized antisemite," in a 1939 "Letter to the Leader of the Jews," quoted in Goodman and Miyazawa, Jews in the Japanese Mind, pp. 130-31.

[18] Marvin Tokayer and Mary Swartz, The Fugo Plan: The Untold Story of the Japanese and the Jews during World War II (New York: Paddington Press, 1979), esp. pp. 44-61. (The very tasty but extremely poisonous fugo fish can be consumed safely only if the poisonous parts are expertly removed; likewise, Jews were seen as potentially very useful but fatal if mishandled.)

July 10, 2011 update: A new example from debt-ridden Greece, as reported by the Jerusalem Post:

Desperate for the international community's financial support and perhaps slightly overestimating world Jewry's power and influence, the Greeks are hoping that improved relations with Israel and the American Jewish community will further their economic interests. Diaspora Jewry is viewed by the Greeks as being critically influential in international finance and potential investors in their foundering economy.

Christian Pineau, foreign minister of France, 1956-58.

Nov. 1, 2012 update: In an article by David Makovsky and Amanda Sass looking at the implications of a non-strike by Israeli forces on Iran, "By Avoiding a Strike on Iran before U.S. Election, Israel Is Learning from History," the authors contrast today's situation with that of 1956, when the Israelis joined the French and British just days before the U.S. elections to strike Egypt.

They note that the idea for an attack on Suez "was not Israel's, as some may believe, but was the initiative of France's Foreign Minister Christian Pineau. He was confident that the U.S. would not criticize its friends for a firm stance against a hostile Soviet Union and a difficult President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt." But he miscalculated the American reaction, in part because "he overstated the strategic value of the American Jewish vote for Eisenhower. If he had been more perceptive or informed about the American national mood, he would have realized that Eisenhower would win by a landslide against candidate Adlai Stevenson in 1956, and therefore, was not worried about the Jewish vote, which he did not win anyway."

Jan. 25, 2016 update: China's turns out to be similar Japan in knowing little about Jews but noting the antisemitic antagonism to perceived Jewish power and wealth as a model to learn from, explains James Ross in Tablet magazine. An excerpt:

Most of the Chinese authors who write about Jews really don't know much about them. They use the success of Jews, especially in business and education, to promote values the Chinese traditionally cherish, such as hard work and knowledge or, in China's burgeoning market economy, getting rich. ...

Best-selling Chinese books have been filled with outrageous claims about Jews for decades. Most of the claims create a positive attitude about Jews, but they also perpetuate stereotypes and misunderstandings about how Jews make money and raise their children. ...

Although many of the blogs are exaggerated or false in their praise of the Jews, some seem openly anti-Semitic.