Israel is a small country and twelve years a short time; a full-length book on this subject suggests a very detailed narrative, and that is what Howard M. Sachar has given us. Even so, much of the story is familiar. Anyone who follows the news will know the outlines of the account told here: Israel's difficult years coping with rising oil prices, the decline of the Labor Party, the election of Menachem Begin, the peace treaty with Egypt, the failed war in Lebanon, and, since 1984, the National Unity Government's unlikely success.

Israel is a small country and twelve years a short time; a full-length book on this subject suggests a very detailed narrative, and that is what Howard M. Sachar has given us. Even so, much of the story is familiar. Anyone who follows the news will know the outlines of the account told here: Israel's difficult years coping with rising oil prices, the decline of the Labor Party, the election of Menachem Begin, the peace treaty with Egypt, the failed war in Lebanon, and, since 1984, the National Unity Government's unlikely success.

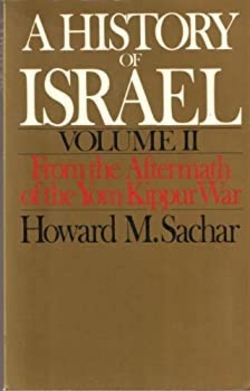

Even if these events figured prominently in the American media, reading about them in A History of Israel, volume II (the first volume covered Israel from the early Zionists and ended with the 1973 war) makes them far more comprehensible. When a clear-sighted historian like Howard M. Sachar recounts recent events, he turns a jumble of facts into an ordered, meaningful progression.

Although the author touches on all aspects of Israeli public life, he takes much less interest in foreign policy than in the turbulence of domestic politics. And he has strong views on this matter. While giving the Likud Party and Menachem Begin their due and castigating the Labor Party for its faults, his account is suffused with a preference for Labor. Indeed, the moral underlying A History of Israel is of Israel's deterioration under Begin and its need to recover with another term of Labor.

Sachar wears this bias on his sleeve. He describes Labor leader Shimon Peres, on taking office as prime minister in 1984, as "a trim, well-tailored man of ruddy complexion and a full head of glossy hair, [who] stood at the maturity of his powers and experience." In contrast, he introduces opposition politician David Levy a few lines later as "an under-educated Cherut [i.e., Likud] party hack" who rose to become "the acknowledged voice of right-wing populism." Likud's actions are "bizarre" and "provocative," its military policy "bombastic," and its adherents "abrasive." No such terms are ever applied to the Labor Party.

Even more unfair than his adjectives are some of the criticisms of Likud. That Israel in 1984 had but 15 students in school per 1,000 inhabitants, in contrast to Jordan's 17 and the Palestinians' 20, surely reflects the higher birth rate among the Arabs - not, as Mr. Sachar implies, the fact that Likud's minister of education and culture was an Orthodox Jew who favored religious schools over secular ones.

He criticizes with particular severity the Oriental Jews who provide most of Likud's support. The Orientals' rejection of Israeli guilt for the Sabra and Shatila massacres prompts Mr. Sachar to observe that "the subtlety of indirect responsibility was beyond them." They even lacked the sense to worry about the rapid drop in foreign currency reserves that followed a flooding of imported consumer items: "Begin's grateful oriental constituency ... seemed hardly responsive to the long-range implications" of this indulgence.

The most original and provocative theme in this book is the author's concern that Israelis will tear their state apart. He fears for its democracy and for its very being. Writing about the Likud Party's feeble response to Israeli settlers taking the law in their own hands in early 1982, he tells of "a mood of growing desperation," in which, if the state's existence was not yet at peril, "its character as a viable democracy ... unquestionably was approaching the threshold of its acutest vulnerability."

More unexpected, Mr. Sachar sees the state's future as still open to doubt. Even as many Arabs have come to accept Israel's existence as a permanent reality, he notes the fragility of the whole Zionist undertaking. In a key passage, he notes Israel's many vulnerabilities:

A majority of Jews in free, Western nations did not wish to emigrate to the Jewish homeland. The promise of Israel as the sure and certain haven for the Jewish people was itself open to question. Israel was the only Jewish community in the world, after all, that was calling on Jews elsewhere to save it from "another Holocaust," a threat that its very establishment was supposed to avert. Jewish statehood had also been envisaged as a guarantee of Jewish economic self-sufficiency and productivity. The opposite now seemed to be the case. Israel's economy was a shambles, the nation was emerging as one of the "developed" world's chronic mendicants. Neither was the historic assumption borne out that a Jewish state would effect a Jewish vocational transformation ... the business and professional patterns of the Diaspora were increasingly being replicated on Israeli soil. To an extent that would have shocked [early Zionists], so was the reviving ultra-Orthodoxy of the nineteenth-century shtetl.

Like many knowledgeable students of Israel, Mr. Sachar regards the greatest dangers as internal: Jews, not Arabs, threaten the fate of Israel.

Profound and insightful though it is, this analysis points to my one major criticism of A History of Israel. Mr. Sachar has immersed himself so thoroughly in matters Jewish and Israeli that he ignores the regional canvas; the result is an odd naïveté. How could anyone familiar with the brutality of recent Middle East politics call Israel's appropriation of Bedouin grazing areas for a nature preserve a "cruel tragedy?" Similarly, Mr. Sachar exposes his sheltered perspective when he dubs the situation on the West Bank as one of "flailing lawlessness;" to a student of Middle Eastern life, the West Bank appears much more regular than that.

This leads to a more general observation about the study of Israel. The time has come to take more seriously Israel's Middle East context. True, Israel's culture and political system are ultimately Western, but the state is located in the Middle East, its population is predominantly born there, and its fate is driven by Middle Eastern events. For these reasons, Israel is best understood in the framework of its region.

Daniel Pipes, author of In the Path of God: Islam and Political Power, is director of the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia and editor of its quarterly journal, Orbis.