On March 20, 2002, officers from the FBI, customs, immigration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), raided nineteen offices and residences in Virginia and Georgia in the largest action against suspected terrorism-financing in American history. One of the targets of "Operation Green Quest" was the Washington, D.C.-area residence of Iqbal Unus, a nuclear physicist, along with his wife Aysha Nudrat and their 18-year-old daughter Hanaa.

Iqbal Unus. |

David Kane the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement special agent who signed the 106-page affidavit that justified the search;

Rita Katz, a private counterterrorism specialist and director of what is now called the SITE Intelligence Group; and

"All unknown named federal agents … who searched plaintiffs' home." Those agents, the Unus family claimed, "knew or should have known that the affidavit did not contain probable cause for the search … for financial documents." (The agents, later named, numbered eleven in all: four customs agents, four Internal Revenue Service agents, an Immigration and Naturalization Service agent, a Secret Service agent, and a postal inspector.)

These defendants together stood accused of conspiring to "contrive allegations" that documents relevant to the financing of terrorism were located at their house. In plain English, the Unus family alleged that Kane, Katz, and the federal agents fabricated reasons for the raid.

In other words, the Unus family ascribed responsibility for the search of their house, a sovereign decision of the U.S. government, to specific federal employees and, even more bizarrely, to a private person (Katz) who had never served as a U.S. government employee. They justified suing Katz because she had claimed in her autobiography, Terrorist Hunter, and on the CBS program 60 Minutes to having unearthed the information that led to Kane's affidavit. Accordingly, the Unus family deemed her "the impetus" behind the search warrant and the source for its "every piece of information."[1]

The Unus lawsuit, only recently settled, warrants scrutiny because it fits a common pattern of what I call predatory exploitation of U.S. courts by Islamists. It raises several questions: What did the Unus family hope to achieve from its lawsuit? How does this incident fit into the larger scheme of Islamist ambitions? How can this abuse of the U.S. legal system be prevented?

The Lawsuit

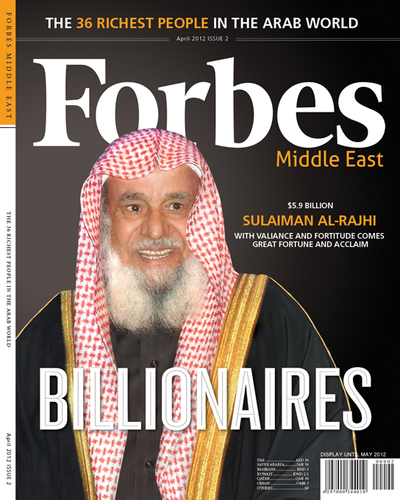

The main target of the raids was a small office building at 555 Grove Street in Herndon, Virginia, the site of over a hundred closely related commercial companies, think tanks, religious organizations, and non-profit charities controlled by a handful of individuals, known collectively as the "Safa Group," after one of the major companies in that network, or the "SAAR network," after the initials of Sulaiman Abdel-Aziz al-Rajhi, the Saudi financier alleged to have funded the enterprises.

555 Grove Street, Herndon, Virginia. |

Kane's affidavit stated that several members of the Safa Group "maintained a financial and ideological relationship with persons and entities with known affiliations to the designated terrorist Groups PIJ [Palestinian Islamic Jihad] and HAMAS." The affidavit connected Iqbal Unus to the Safa Group in two main ways. First, it said he worked for the Safa Group via e-mail accounts registered to his home address, serving variously as manager, officer, director, or administrative and billing contact. He acted in these capacities for such Safa Group companies as the International Institute of Islamic Thought, the Fiqh Council of North America, the Child Development Foundation, the Sterling Charitable Gift Fund, Sterling Management Group, and the International Islamic Charitable Organization.

Sulaiman Abdel-Aziz al-Rajhi on the cover of Forbes Magazine. |

Second, the internet registration for the Fiqh Council of North America's website, http://www.fiqhcouncil.org/, "identifies Iqbal Unus as the billing and administrative contact for this domain, with an email contact address of iqbalunus@aol.com. According to records received from America Online, the email account iqbalunus@aol.com is subscribed to by Iqbal Unus at 12607 Rock Ridge Road in Herndon." (This fact had particular relevance in justifying a search of the Unus residence).

This documentation, the U.S. government argued, established the Green Quest raids as "completely lawful." The judge in the Unus case, Leonie M. Brinkema, agreed. In January 2005, she made short shrift of the Unus family's argument, dismissing it not just with prejudice[2] but with disdain: "there's no way in which Ms. Katz could ever be held liable under this fact scenario."[3] Further, she found the Unus family's claim against Katz "frivolous, unreasonable, or groundless," and ordered them to pay her $41,105.70 to reimburse her legal expenses.

U.S. District Court Judge Leonie M. Brinkema. |

In May 2009, a three-judge panel of the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously upheld Brinkema's decision, finding that "the plaintiffs have failed to sufficiently identify any factual misrepresentations in the Affidavit, and therefore, have failed to identify how Katz caused any injury." The appellate court reversed Brinkema only on one small but significant point – her ruling that the Unus family must pay Katz's $41,105.70 for her legal fees, on the grounds that Unus' allegations did deserve "serious and careful consideration in a court of law." The Unus legal effort apparently completely bombed.

Purposes

This, however, is too narrow a prism through which to see the Unus lawsuit. Its goal would seem not to be to prevail in the courtroom but to attain multiple objectives outside the courtroom:

To divert counterterrorism investigators, specialists, and prosecutors. The lawsuit forced Kane, Katz, and the others to waste time working with lawyers and explaining to judges an enormously complex investigation rather than proceeding with further counterterrorism efforts. (The Unus' own lawyer admitted it took her eight hours a day for five months to understand the Kane affidavit.)[4]

To silence these same counterterrorists, who for the years during which the court proceedings took place could not speak freely about Unus or related subjects.

To obstruct their work. For example, Unus argued that law enforcement officers must be instructed about Muslim customs before searching a Muslim-owned residence.[5]

To distract attention. The Unus case followed on several other (ultimately successful) prosecutions of the Safa Group. Abdurahman Alamoudi, one of its major figures, signed a plea agreement in 2003 admitting his illegal financial dealings with Libya, a designated terrorist state, and participating in a plot to assassinate then-Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah; he is currently serving a twenty-three year prison sentence. Soliman Biheiri, also closely tied to the Safa Group, was convicted in 2003 and sentenced to 13 months and a day in prison, following which he was to be deported. Youssef Nada, another associate, was designated a terrorist sponsor by the U.S. Treasury Department and the United Nations Al Qaeda Sanctions Committee, while his Bank Al Taqwa was placed on the Terrorist Exclusion List.

To glean information useful for Unus to defend himself from a possible indictment, which he might have feared given that some of his associates had been already brought to trial.

To bankrupt private individuals who try to expose terrorists. Katz's legal bill came to $41,105.70 and she also faced two other related lawsuits. (Soon after Katz in May 2003 described on television her role in the raids and the alleged links of the Safa Group to terrorist organizations, two Safa Group organizations sued her, the SITE Institute, and CBS for defamation, seeking $80 million in compensation. Subsequently they dropped their case against all three defendants. A chicken farm in Georgia, also raided in March 2002 and described by the Kane affidavit as "a Safa Group company," filed a similar lawsuit for an unspecified amount.)

To garner publicity for Islamists and win them sympathy as victims of government persecution.

More broadly, predatory lawsuits fit a pattern of Islamists exploiting the West's own tools against itself, as in their hijacking of airliners, reliance on the Internet, and (in Spain) swaying the political landscape via elections. Longshot suits such as the Unus one also reap wider benefits for Islamists:

First, by ascribing responsibility for sovereign U.S. governmental actions to private individuals such as Katz, they bolster a conspiracist trend to undermine its authority. Thus has Richard Perle been blamed for the Bush administration's decision to overthrow the Saddam Hussein regime and Steven Emerson and I held responsible for a federal raid on InfoCom Corporation in September 2001 as well as for Operation Green Quest itself.

Second, Islamists make a practice of misusing the legal system with predatory lawsuits against individuals, organizations, and companies who, like Katz, dare report on them:

The Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development, deemed in 2001 a "Specially Designated Global Terrorist Entity," sued the Dallas Morning News, four of its reporters, and its parent company Belo Corp., accusing them of defamation.

The Global Relief Foundation sued the New York Times, ABC News, the Associated Press, the Boston Globe, the Daily News, Hearst Communications, and seven journalists for reports in 2001 that it was funneling money to terrorists.

Seven Dallas-area Muslim groups sued Joe Kaufman of "Americans Against Hate" for an article detailing ties between the Islamic Circle of North America and terrorist groups (Hamas, Hezbollah, and possibly Al Qaeda).

The Islamic Society of Boston brought a law suit against 17 defendants after news outlets and Jewish groups alleged that the ISB had connections to terrorist organizations and had purchased land from the City of Boston for below-market value

Khadija Ghafur, superintendent of the now-defunct Gateway Academy, initiated a libel suit against the Anti-Defamation League on the grounds that its stated concerns (about the academy having connections to the terrorist organization Al-Fuqra and using taxpayer funding to provide religious instruction) were in fact part of ADL's "long-standing effort to denigrate Muslims as part of their advocacy for Israel."

CAIR brought a defamation lawsuit against former Representative Cass Ballenger (a Republican from North Carolina), after he spoke of having reported CAIR to federal authorities as a "fundraising arm for Hezbollah." CAIR also filed suit alleging "libelous defamation" against Andrew Whitehead of Anti-CAIR for his terming CAIR "a terrorist supporting front organization" founded by members of Hamas.

CAIR-Canada, CAIR's Canadian adjunct, sued David Harris, formerly of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, along with Ottawa's CFRA radio station, because Harris, speaking on CFRA, raised CAIR's extremist connections and called for Canadian media to investigate the nature of any relationship between CAIR and CAIR-CAN before treating CAIR-CAN as a legitimate voice of moderate Canadian Muslims.

Finally, Islamists make life difficult for the U.S. government itself by bringing lawsuits against agencies tasked with maintaining security:

A Georgia chicken farm alleged to be part of the Safa Group won much attention for suing the government because its attorney, Wilmer Parker, a former assistant U.S. attorney, claimed that federal prosecutors "knowingly made false statements" to obtain the search warrant for the raids. The lawsuit was dismissed.

Five U.S. Muslim citizens got CAIR and ACLU support to sue the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol for detaining them upon their return from an Islamic conference in Toronto, a conference which the patrol believed was a potential meeting place for terrorists. The suit was dismissed.

Abdel Moniem Ali El-Ganayni, a nuclear physicist of Egyptian origins, sued the Department of Energy after it revoked his security clearance following an investigation that revealed he had "knowingly established or continued sympathetic association with a saboteur, spy, terrorist, traitor, seditionist, anarchist, or revolutionist, espionage agent, or representative of a foreign nation whose interests are inimical to the interests of the United States."

Win or lose, the Islamists' legal gambits disrupt the work of law enforcement.

Such predatory lawsuits also carry risks, however. Not only are they expensive and likely to go down in flames, as did the Unus effort, but they can backfire and wreak damage on the plaintiffs. Plaintiffs can look foolish when they must suddenly drop lawsuits, as did the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) in its case against Andrew Whitehead or KinderUSA in its case against Yale University Press and Matthew Levitt of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Worse yet, Enaam Arnaout, director of the Benevolence International Foundation (BIF), made statements in BIF's suit against the U.S. government that led to his being charged with obstruction of justice, convicted, and sentenced to 121 months in jail.

Policy Recommendation

The Unus and other lawsuits point to an abuse of the legal system in need of remedy. Fortunately, important steps toward such a remedy does exist, albeit usually only for private individuals: that would be Anti-SLAPP legislation, where SLAPP stands for "Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation." A SLAPP, according to the California Anti-SLAPP Project, generally is "a (1) civil complaint or counterclaim; (2) filed against individuals or organizations; (3) arising from their communications to government or speech on an issue of public interest or concern." When these conditions are met, the court can make the plaintiff pay the defendant's attorney's fees and other legal costs.

The legislation works. The ADL filed an anti-SLAPP motion against Khadija Ghafur, prompting the court to dismiss her case. KinderUSA dropped its lawsuit as soon as the defendants made an anti-SLAPP motion, even before the court ruled on it. But Anti-SLAPP statutes are only spottily available; nearly half the states and the federal government have not enacted them. Also, in too many instances the legislation is too narrowly construed by courts, making it an ineffective tool for defendants. For example, in the ISB case, the judge denied an anti-SLAPP motion on the grounds that only activities directly related to petitioning the government, not media activities, are protected by Massachusetts' anti-SLAPP statute.

It is time to enact a uniform, federal anti-SLAPP legislation, as is now being proposed under the name of the "The Citizen Participation in Government and Society Act." Among other benefits, this will protect researchers and activists dealing with radical Islam and terrorism from predatory use of the legal system. If the war against radical Islam is to be won, all avenues of attack, including the courts, need to be battened down.

Mr. Pipes is director of the Middle East Forum and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University.

[1] Deborah St. John, "Transcript of Motions Hearing," in Iqbal Unus et al. vs. David Kane et al., 11 January 2005, p .31.

[2] Leonie M. Brinkema, "Order," in Iqbal Unus et al. vs. David Kane et al., March 11, 2005, p. 3.

[3] Leonie M. Brinkema, "Transcript of Motions Hearing," in Iqbal Unus et al. vs. David Kane et al., January 11, 2005, p. 7.

[4] Deborah St. John, "Transcript of Motions Hearing," in Iqbal Unus et al. vs. David Kane et al., January 11, 2005, p. 27.

[5] Deborah St. John, "Transcript of Motions Hearing," in Iqbal Unus et al. vs. David Kane et al., January 11, 2005, p.33.

Aug. 21, 2011 update: Michelle Boorstein looks at Iqbal Unus in "A founding father of American Islam struggles to put raids behind him."