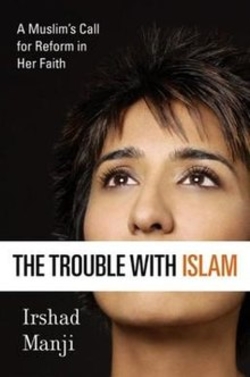

"You will sooner or later pay for your pack of lies," read one threatening message last week to the author of The Trouble with Islam: A Wake-up Call for Honesty and Change.

"You will sooner or later pay for your pack of lies," read one threatening message last week to the author of The Trouble with Islam: A Wake-up Call for Honesty and Change.

In that book, just released in Canada, Irshad Manji, 34, explores such usually taboo themes as anti-Semitism, slavery and the inferior treatment of women with what she calls an "utmost honesty."

"Grow up!" she scolds Muslims. "And take responsibility for our role in what ails Islam."

Although a TV journalist and personality, Manji - a practicing Muslim - brings real insight to her subject. "I appreciate that every faith has its share of literalists. Christians have their Evangelicals. Jews have the ultra-Orthodox. For God's sake, even Buddhists have fundamentalists. But what this book hammers home is that only in Islam is literalism mainstream."

For her efforts, Manji has been called "self-hating," "irrelevant," "a Muslim sellout" and a "blasphemer." She is accused of both "denigrating Islam" and dehumanizing Muslims.

This outpouring of hostility prompted Manji to hire a guard and install bullet proof glass in her house. The Toronto police acknowledge "a very high level of awareness" about her security.

Manji's predicament is unfortunately all too typical of what courageous, moderate, modern Muslims face when they speak out against the scourge of militant Islam. Her experience echoes the threats against the lives of such writers as Salman Rushdie and Taslima Nasreen.

And non-Muslims wonder why anti-Islamist Muslims in western Europe and North America are so quiet?

Anti-Islamist Muslims - who wish to live modern lives, unencumbered by burqas, fatwas and violent visions of jihad - are on the defensive and atomized. However eloquent, their individual voices cannot compete with the roar of militant Islam's determination, money (much of it from overseas) and violence. As a result, militant Islam, with its West-phobia and goal of world hegemony, dominates Islam in the West and appears to many to be the only kind of Islam.

But anti-Islamist Muslims not only exist; in the two years since 9/11, they have increasingly found their voice. They are a varied lot, sharing neither a single approach nor one agenda. Some are pious, some not, and others are freethinkers or atheists. Some are conservative, others liberal. They share only a hostility to the Wahhabi, Khomeini and other forms of militant Islam.

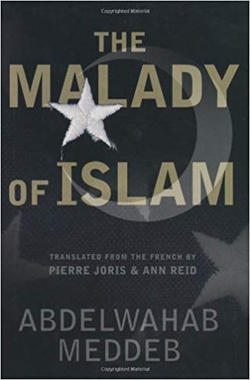

They are starting to produce books that challenge the Islamists' totalitarian vision. Abdelwahab Meddeb of the Sorbonne wrote the evocatively titled Malady of Islam, in which he compares militant Islam to Nazism. Akbar Ahmed of American University wrote Islam Under Siege, calling for Muslims to respect non-Muslims.

They are starting to produce books that challenge the Islamists' totalitarian vision. Abdelwahab Meddeb of the Sorbonne wrote the evocatively titled Malady of Islam, in which he compares militant Islam to Nazism. Akbar Ahmed of American University wrote Islam Under Siege, calling for Muslims to respect non-Muslims.

Other outspoken academics include Saadollah Ghaussy formerly of Sophia University in Tokyo, Husain Haqqani of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Salim Mansur of the University of Western Ontario and Khaleel Mohammad of San Diego State University.

Journalists such as Tashbih Sayyid of Pakistan Today and Stephen Schwartz (who has written for the Post and The Weekly Standard, among others) are on the front lines against militant Islam in the United States, as is the writer Khalid Durán. Tahir Aslam Gora has the same role in Canada. The ex-Muslim who goes by the pseudonym Ibn Warraq has written a series of books intended to embolden Muslims to question their faith.

A number of organizations are anti-Islamist, including the Islamic Supreme Council of America, the Council for Democracy and Tolerance, the American Islamic Congress and Shi'ite organizations, such as the Society for Humanity and Islam in America. A number of Turkish organizations have a determinedly secular cast, including the Atatürk Society and the Assembly of Turkish American Associations.

Some anti-Islamists have acquired public roles. Ayaan Hirsi Ali in Holland, who has called Islam a "backward" religion, is a member of the Dutch parliament. Naser Khader in Denmark is also a member of parliament and a secularist who calls for full Muslim integration with the Danes.

The weak standing of anti-Islamist Muslims has two major implications.

- For them to be heard over the Islamist din requires help from the outside - celebration by governments, grants from foundations, recognition by the media and attention from the academy.

- Those same institutions must shun the now-dominant militant Islamic establishment. Moderates have a chance to be heard when Islamists are repudiated.

Promoting anti-Islamists and weakening Islamists is crucial if a moderate and modern form of Islam is to emerge in the West.