Like most Americans, I connect the Palestine Liberation Organization with violence and extremist rhetoric. I view it as the creature of the Arab states and the Soviet bloc and assume that it aims to destroy the Israeli state-despite occasional signals to the contrary. Also, I am struck by how little the PLO has achieved in 20 years, despite the massive amounts of arms, money, and diplomatic support it has enjoyed.

Like most Americans, I connect the Palestine Liberation Organization with violence and extremist rhetoric. I view it as the creature of the Arab states and the Soviet bloc and assume that it aims to destroy the Israeli state-despite occasional signals to the contrary. Also, I am struck by how little the PLO has achieved in 20 years, despite the massive amounts of arms, money, and diplomatic support it has enjoyed.

There is, of course, another view, the one Helena Cobban presents in her book, The Palestinian Liberation Organisation. For Cobban, the PLO is a spunky movement that has achieved wonders by tapping the national spirit of its people. She shows how it has overcome the meddling of Arab rulers, the brutality of Israel, and its own fissiparous tendencies to emerge as a major force in the Middle East.

The author lets nothing get in the way of her admiration for the PLO, and especially for Fateh, its largest component. "Heroic," "triumphant," "patient," and "well-trained" are some of the adjectives she uses. She pays tribute to its "vitality and power," "native-born vigour and resilience," "increasing effectiveness," "the effectiveness of the defence of Beirut," "the shared pragmatism of its members," and the "sophistication" of its decision-making process." George Habash, probably the most ruthless of all PLO leaders, she calls "a respected elder statesman" of the Palestinian movement.

Cobban uses language so delicate, even timorous, when discussing PLO troubles that her account takes on the tone of an authorized history. When she refers to the displeasure of Fateh rebels with Arafat's conduct, she conspicuously avoids mentioning what their complaints were. If many observers believe the PLO presence in Lebanon sparked that country's civil war, Cobban only admits that it "imposed quite some strain on the fragile system of that tiny east Mediterranean nation." In the one direct reference to PLO terror, Cobban skirts the issue by means of an irrelevancy: "Though it is extremely doubtful if this was a unanimous or even a majority decision inside the Fateh leadership, [it] sanctioned the launching of a selective terror campaign against Israeli and Jordanian targets on a world-wide basis." Why emphasize the way in which the decision was reached? Reading Cobban on the PLO is like reading Pravda on Soviet economic successes.

In contrast, the principal modifier for Israel is "harsh." We read of its "harsh retaliations," "harsh political measures," "harsh set of policies," "harsh military attacks," "harsh and rapid responses," and "harshly 'pre-emptive' policy." From these came "increasing suffering," "a bloody reprisal raid," "a particularly savage raid," and "provocations." Ariel Sharon attracts much of Helena Cobban's abuse: "A figure long notorious in Palestinian eyes for his brutality," he "threw all the nasty tricks of ultra-modern military technology" against Beirut in 1982 in the effort "to terrorise" Palestinians to leave Lebanon. The U.S. public reacted in "horror" to the "excesses" committed by the Israelis in Lebanon.

Fateh's enemies are also Cobban's; she loyally denigrates whoever stands in its way. Arab rulers are characterized by "weakness and timidity," King Hussein ruled the West Bank as a "fiefdom" until 1967, and Anwar Sadat's peace initiative with Israel was "egregious." In Lebanon, the Shi'is' way of life "had changed little since the days of feudalism" and the Christians "plotted endlessly" against the Palestinians. Ronald Reagan has a "dangerously slight" knowledge of the Middle East. The unique negative references to any Palestinians are to Abu Nidal and the Black September Organization (whose 1973 attack in Khartoum she terms "bloody"), both of which have been denounced by Fateh.

Even as court historian of the PLO, however, Cobban does a poor job. Her book is replete with spelling mistakes in English and Arabic, missing references, inappropriate colloquialisms, and wrong dates. Worse, there are important distortions of fact. Jewish acceptance of the United Nations partition plan in 1948 disappears in Cobban's account: "The existing Jewish leadership in Palestine did not reject this proposal outright (though the extremist Jewish group led by Menachem Begin did do so)." The author appears to want to hide the fact that the Jews accepted partition without actually saying so. And in the next paragraph, she writes that the "total number of Arab soldiers mustered in 1948 came to only 24,000--far fewer than the number of fighters raised by the Jewish groups in Palestine." This and many other assertions are simply wrong.

Beyond specific objections, Helena Cobban has written a book that lacks either new facts or new interpretations. She clearly knows her subject intimately; a pity, then, that she does so little with it. (Aaron David Miller's recent Center for Strategic and International Studies monograph, The PLO and the Politics of Survival, provides all the critical information more compactly and with admirable dispassion.) One cannot help but wonder why a major university press such as Cambridge should publish so partisan and ephemeral a study.

PLO in Lebanon contrasts with The Palestinian Liberation Organisation in two ways: it conforms to the majority view of the PLO as a terrorist organization and it consists mostly of documents. The bulk of its contents comes from the papers collected from PLO offices in Lebanon by the Israelis in 1982. These provide a first- hand glimpse into the PLO's astonishing range of international connections, its plans for attacking U.S. air bases, its guidelines for shelling Israeli towns, and the like.

PLO in Lebanon contrasts with The Palestinian Liberation Organisation in two ways: it conforms to the majority view of the PLO as a terrorist organization and it consists mostly of documents. The bulk of its contents comes from the papers collected from PLO offices in Lebanon by the Israelis in 1982. These provide a first- hand glimpse into the PLO's astonishing range of international connections, its plans for attacking U.S. air bases, its guidelines for shelling Israeli towns, and the like.

But most fascinating is the conversation between Arafat and Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet foreign minister, perhaps the first verbatim transcript of a Kremlin discussion ever seen in the West. On November 13, 1979, only days after the seizure of the American hostages in Tehran, Arafat dismissed U.S. efforts to involve him in their release, saying "We are not mediators. We are on the Iranian side, and agree to what Khomeini agrees to." For his part, Gromyko noted the correctness of the U.S. position legally with regard to the hostages but added that the U.S.S.R. would not help the U.S. because "we do not wish to protect American interests."

In the course of their talks, Arafat admitted that PLO diplomatic success in Europe "is based on Europe's need for Arab oil." Later, Gromyko offered the PLO an astonishing commitment of automatic support by the entire Soviet bloc: "We will back every proposal and every plan which you submit to the UN. This support also applies to our socialist comrades." In return, he asked Arafat to make "tactical concessions" on the matter of recognizing Israel, so that Moscow could more easily pressure Washington to recognize the PLO. Implied in this, of course, is the Soviet desire to weaken the U.S. relationship with Israel, the main barrier to its progress in the Middle East.

In these ways, PLO in Lebanon provides a remarkably direct and nontechnical insight into PLO operations.

June 10, 1984 update: Cobban replies to this review and I reply to her today at "Debating Helena Cobban's 'The Palestinian Liberation Organisation': Letters to the Editor."

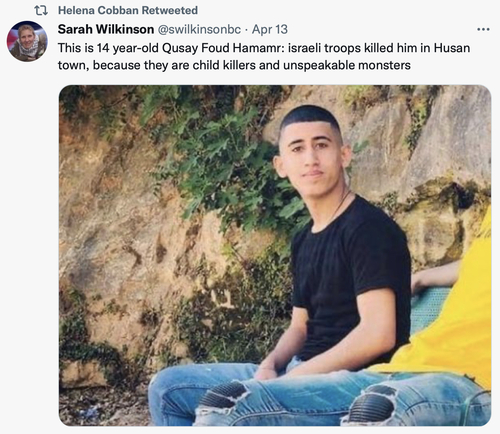

Apr. 18, 2022 update: A retweet by Cobban prompted me to respond on Twitter:

.@HelenaCobban, who just retweeted that Israeli troops "are child killers and unspeakable monsters," has long been an obsessive #antiZionist.

See my review of her unspeakable book on the PLO, her effort at a reply, and my retort.https://t.co/hVxFdbUWQThttps://t.co/VbBYpzYu2j

— Daniel Pipes دانيال بايبس