Two aspects of the Iraq-Iran conflict are easy to explain: which side began the fighting and why hostilities erupted in September 1980. Except for official Iraqi spokesmen, there is nearly universal agreement that Iraq initiated hostilities on Sep. 2, when it sent troops into Iran near Qasr-e-Shirin, that it escalated the conflict on Sep. 17 (by renouncing a border treaty with Iran), and that it began a full-scale war on the 22nd by sending warplanes to attack ten Iranian airfields. In each case, Iran merely responded to Iraqi initiatives.

Two aspects of the Iraq-Iran conflict are easy to explain: which side began the fighting and why hostilities erupted in September 1980. Except for official Iraqi spokesmen, there is nearly universal agreement that Iraq initiated hostilities on Sep. 2, when it sent troops into Iran near Qasr-e-Shirin, that it escalated the conflict on Sep. 17 (by renouncing a border treaty with Iran), and that it began a full-scale war on the 22nd by sending warplanes to attack ten Iranian airfields. In each case, Iran merely responded to Iraqi initiatives.

Iraq's leaders chose an excellent moment to attack Iran. September is the right season for an infantry assault, and in late 1980 both superpowers had focused their attention elsewhere (Afghanistan and Poland in the case of the Soviet Union, the Iranian hostage crisis and presidential elections in the U.S. case).

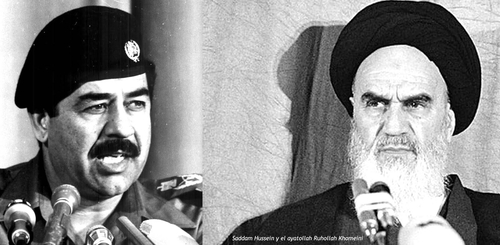

It was also a time when the Iranians seemed least capable of defending themselves. One and a half years after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned triumphantly to Tehran, the revolution had frayed: oil revenues remained low while inflation and unemployment ran high; many Iranians, especially Kurds and leftists, had openly rebelled against their government; and, most important, the large and well-armed military forces built up for years by Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi had apparently collapsed. Morale plummeted, discipline eroded, and troops deserted as the armed forces fell into deep disfavor under Khomeini. The mullahs purged officers, canceled weapons purchases, terminated military privileges, and established a rival force that was loyal to them (the Pasdaran, or Revolutionary Guards). U.S.-supplied materiel had been cut off on Nov. 9, 1979, five days after the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, though Tehran did manage to acquire some spare parts through third parties. Reports perhaps exaggerated the decline in Iran's military forces, but the general consensus was that Iran could no longer stand up to Iraq. Thus, Iraqi leaders had many reasons to attack when they did.

But why did the Iraqis attack? What goals prompted President Saddam Husayn's regime to confront Iran and provoke a large-scale war? What made it worth risking oil facilities, wide international disapproval, loss of revenues, and domestic unrest? Assuming Saddam Husayn is not one to act rashly or foolishly - even critics acknowledge his pragmatism - one must conclude that he had serious reasons for making war in September 1980.

Most analysts stress two factors: "general hostility" between the two sides and Ba'th party fears that the Khomeini government might stir up a Shi'i rebellion in southern Iraq. I shall argue, however, that while these factors had some role in worsening relations, they hardly entered into the decision to attack Iran; rather, the war resulted primarily from territorial disputes, especially the centuries-old conflict over the boundary at the Shatt al-'Arab River.

1. General Hostility

As tensions between Iraq and Iran rose in April and September 1980, many observers emphasized the two countries' political and religious differences, citing animosities that began in the seventh century. For instance, the Levant correspondent for The Economist wrote:

This is one of the world's oldest conflicts across a primarily racial divide. ... The origins of the present hostilities between Iraq and Iran can be traced all the way back to the battle of Qadisiya in southern Iraq in 637 A.D., when an army of Muslim Arabs put paid to a bigger army of Zoroastrian Persians and to the decadent Sassanian empire.

Geoffrey Godsell went even further in The Christian Science Monitor, calling the Arab-Persian frontier "one of the great ethnic and cultural divides on the earth's surface." When Iraq invaded Iran, The New York Times explained this as an "ancient struggle" and a continuation of the Arab effort begun in 637 to subdue the Persians. Three years later, when Iranian forces invaded Iraq, The Economist suggested this was the Shi'a of Iran's "chance at revenge" for the massacre at Karbala in A.D. 680.

But this is nonsense, and for two reasons. First, it takes too seriously the combatants' war propaganda. The regimes in Baghdad and Tehran need to motivate their troops, so they hark back to historic conflicts. There is no reason, however, to make these inspirational messages as factors in the outbreak of war.

Second, as Narayanan Balakrishnan of the New Nation (Singapore), has shown, "nothing delights journalists more than looking for historical parallels to current events. ... Nothing like a dash of history to add profundity to a mundane current event; it seems to be the current journalistic dictum. A closer look, though, shows that many of these 'historical' parallels are on very shaky ground." Balakrishnan goes on to observe, very astutely:

It is no accident that historical generalizations are made more often about the developing countries than about Europe. It is not that the French and Germans have a special gift for forgetting the past 80 years, whereas the Sunnis and Shias cannot forget grudges from 12 centuries ago. Few foreign correspondents - and even fewer Western readers - are aware that the history of Asia is also a many-headed hydra, like the history of Europe, and that it can be used to justify almost anything. That is why the Iraq-Iran conflict is more likely to be explained in terms of Shia-Sunni conflict than as the ideological, economic and territorial dispute that it is, whereas the French-German conflicts are explained in terms of common agricultural policy of the EEC without recourse to the events of the two world wars.

Indeed, many differences do separate Iraq and Iran, but their many common elements should also be kept in mind. Both countries are heirs to a shared legacy going back five millennia; both had vital roles in the ancient culture of the Middle East; both fell to Alexander the Great while escaping Roman rule; and both succumbed to Arabian conquerors around A.D. 630. Iraq and Iran had disproportionately large roles in shaping Muslim civilization, contributing some of its greatest figures, its most splendid cities, and its key institutions. Populations in both countries converted massively to Islam and today less than 10 percent of their citizens remain non-Muslim. The two are virtually alone in the world in having a majority population of Twelver Shi'is. Kurdish and Turkic minorities are numerous and powerful.

Today's regimes also share much. Both are republics that obtained power through the spectacular repudiation of monarchs: a bloody coup d'êtat on July 14, 1958, ended the Hashemite dynasty in Iraq, and Iran's Islamic Revolution of 1978-79 toppled the Pahlavi shahs. Reacting against the pro-Western bent of these monarchs, the republican regimes are nonaligned with a distinct anti-U.S. character. Iraq entered the 1980s without having reinstated the diplomatic relations with the United States it had broken on June 7, 1967, in the midst of the Six Day War. Iran under the mullahs compensated for the shah's close times with Washington by blaming the United States for every ill it experienced "from assassination and ethnic unrest to traffic jams [and] drug addiction." The seizure of U.S. diplomats as hostages led to an extraordinary burst of rancor against the United States and a nearly complete rupture in relations.

Both Iraq and Iran enjoy better, though not harmonious, relations with the Soviet Union. Iraq bought military equipment and supported Soviet actions on most international issues for years before it signed a friendship treaty in 1972. But Baghdad remained a free agent, shooting local communists and making overtures to the West from time to time. Khomeinists feared Soviet encroachment and abominated communism, yet they carefully avoided challenging the Soviet Union. Both governments are obsessed with Israel, though the Iraqi concern goes back much further and runs deeper.

Their differences fall into several categories: the Iraqi leaders are Arabs, Pan-Arabists, "Semites," and Sunnis, while the Khomeinists are non-Arabs, Pan-Islamists, "Aryans," and Shi'is. Each of these dissimilarities is claimed to have provoked animosity in Baghdad against Iran.

Arabs versus Iranians. In the ninth century, cultural antagonism between the Arab and Iranian peoples blossomed into a war of words, dubbed the Shu'ubiya. It featured an exchange of colorful insults ("fire worshipers," "lizard eaters," and the like), which has provided literary ammunition that Arabic and Persian speakers drew on through the centuries. Even today, echoes of this clash reverberate in the propaganda surrounding the war, especially from the Iraqi side.

The Shu'ubiya had a serious purpose: Iranians impugned Arabic culture in an attempt to assert the value of their own heritage. If Arabic speakers thought all Muslims must become Arabized, Iranians eloquently demurred. Being a Muslim, they replied, does not mean losing one's identity and becoming an Arab. The point was made, and today Iranians still speak and write Persian. The Shu'ubiya battle - in contrast to the exchange of missiles that began in September 1980 - was fought by the pen alone, and the Shu'ubiya legacy could have had only the vaguest influence on Iraq's decision to go to war.

Further, the distinction between Arab and Iranian had almost no political import before modern times. Until European ideas of nationalism permeated the Middle East, language identified a person's cultural background, while political allegiance depended on religious, geographic, and ethnic factors. To the extent that the notion of an Arab or an Iranian people existed in premodern times, they were defined by cultural, not political, orientations. A dramatic illustration of this comes from the sixteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire in Turkey and the Safavid Empire in Iran were often at war with each other. While the Ottoman sultan reigning in Istanbul made a name for himself writing Persian poetry, the Safavid shah in Isfahan wrote in Turkic; neither worried about the implications of using his opponent's language. Only in the age of nationalism, then, did language take on a political significance that could prompt people to take up arms.

Pan-Arabists versus Pan-Islamists. While campaigning for the presidential elections in January 1980, Abolhassan Bani-Sadr observed that Arab nationalism is hardly better than Zionism. In Baghdad, where the Ba'th party considers Pan-Arabism virtually sacrosanct and Zionism the mortal enemy, this remark caused apoplexy. But Bani-Sadr did not say this just to provoke the Iraqis; his view is in accord with the pan-Islamic ideology that reigned in Iran after the Khomeinists took over in early 1979. The Iranian Revolution brought men to power who have no use for any sort of nationalism - Arab, Iranian, or otherwise - and who despise it as a Western innovation inimical to Islam. Khomeini considers nationalism (like racism) a form of 'asabiya and, as such, a moral abomination.

Pan-Islam calls for political harmony among Muslims. At minimum, existing Muslim states should cooperate; ideally, they should eliminate their borders and unify as one state. This ideology derives from Islam, which stresses the unity of all those who accept Muhammad as God's prophet. Islamic doctrines strongly urge Muslims to follow a single political leader and forbids them from using force against each other. While these goals are obviously impractical (Muslims number over 800 million and stretch from Senegal to the Philippines), Islamic ideals remain vitally important for many Muslims. While they generally recognize that national states cannot be replaced with a single Islamic government, pan-Islamists rarely feel much attachment to existing national units. (In this, they resemble communists, who also accept the present international order of nations without giving it their ultimate loyalty.)

In contrast, pan-Arabism is concerned only with the Arabic-speaking peoples (or, about one-sixth of all Muslims). Pan-Arabism mixes the pan-Islamic urge to unify all Muslims with the nationalist urge to form a single nations. It can be understood as a modern, secular version of pan-Islam. Pan-Arabists resemble pan-Islamists in their hope to create something larger and more meaningful than the existing state system, but they differ in defining their people by language rather than by religion. Some pious Muslims, including many in Khomeini's government, consider this emphasis anti-Islamic. But it is one thing to disagree over ideals and quite another to go to war over them; nothing indicates that the Iranian government's emphasis on pan-Islamic ideals provoked the Iraqis to initiate hostilities.

Once the fighting started though, the theme of pan-Arabism versus pan-Islamism emerged repeatedly. The Iraqi government stressed the nationalistic purpose of the war: patriotic songs on television, a stress on ethnic rivalry with the Iranians, and repeated references to the seventh-century Battle of Qadisiya (when Arabians beat Iranians). In contrast, the Iranian government ignored nationalism; calling its army "the soldiers of Islam" and the Iraqi army the "forces of blasphemy."

Semites versus Aryans. The notion that a racial difference distinguishes Iraqis from Iranians often enters discussions of the factors leading up to the 1980 war. Not only is there no such racial divide between the two peoples, but neither state considers such distinctions important.

Basic truths about racial concepts cannot be repeated too often. The adjectives "Semitic" and "Aryan" refer to families of languages, not to the peoples that speak them. Arabic is related linguistically to several other languages of the Middle East, including Hebrew; modern scholars have called these the Semitic languages in reference to Shem, the eldest son of Noah. Because Semitic tongues share many traits, it is reasonable to expect that the peoples that speak them also share racial, ethnic, and cultural qualities. In the case of small, confined languages, this assumption often holds true, but this is not so with larger, dispersed ones. Peoples are constantly changing languages, so that ties between race and language are loosened with time to the point that they become meaningless.

An example will serve to illustrate this. In medieval times, English was spoken by a small insular nation whose people were usually related to one another. With the expansion of British power around the world, however, English spread to ethnic groups and races on all continents. In the United States alone, English is the mother tongue of people from every race - how can they all be Anglo-Saxons? There is no longer any ethnic or racial implication to speaking English, and the same holds for other major languages, including Arabic.

Arabic spread like English, though a thousand years earlier. It began as a local language and expanded internationally through force of arms. People from Mauritania to Iraq speak Arabic, not just because the Arabians spread out from the peninsula to cover this whole area, but because the Arabians established a new order that encouraged the vanquished peoples to change languages. Most did - hence Arabic's wide distribution today - but some peoples, notably the Iranians, kept their ancestral speech. There is no deep racial meaning here; these events might well have been reversed, with the Iraqis still speaking Assyrian and Iranians speaking Arabic. Thus, except in a purely linguistic sense, those who speak Semitic languages (commonly known as "Semites," a misleading term) share very little in common; the same applies to those who speak Indo-European languages ("Aryans"), including the Iranians.

Of course, the fact that the Semitic-Aryan distinction is misconceived does not preclude it from taking on political significance, as the Nazi experience has shown. But this has not occurred in Iraq and Iran, neither of which considers differences in language family to have much significance (although Ba'thists, as we have seen, do stress the importance of Arabic). In the 1930s, Nazi propaganda reached Iran, inspiring both a change in the official name of the country in many languages from "Persia" to "Iran" and the addition of the sobriquet "Hero of the Aryans" (Aryamehr) to the shah's titles. These pseudoscientific notions, however, did not penetrate deeply; furthermore, by enshrining racism, they directly contradict Islamic principles.

Sunnis versus Shi'is. When Christian churches split, they begin with differences over theology which later take on political significance. In contrast, Islamic schisms start as political quarrels and only later acquire theological overtones. In particular, the greatest divide between Muslims, that separating Sunnis and Shi'is, has powerful political implications. Already in the first decades of Islam, the Shi'a broke off in a dispute over rightful leadership of the Muslim community. While Sunnis accepted the best qualified man from Muhammad's tribe as caliph, Shi'is insisted on restricting the caliphate to one of Muhammad's direct descendants.

Antagonisms remained vivid throughout the centuries. Shi'is had little mundane success, while the Sunnis became numerically dominant and controlled nearly every Muslim government. Twelver Shi'a forces did capture Iran in 1501, however, and have ruled there ever since. Although surrounded by hostile Sunni states, the Iranian Shi'is did hold their own. The government of today's Iraq inherited the traditional Sunni animosity toward Shi'i rule, and that animosity remains strong today. While this factor undoubtedly exacerbated relations once the war began in 1980, there is no indication it had anything to do with the Iraqi decision to make war. Baghdad has far more pressing concerns than ancient grudges.

One of those concerns is the fact that more than one-half of Iraq's population adheres to the same Twelver Shi'i version of Islam that prevails in Iran. This engenders deep fears of a Shi'i rebellion in Iraq.

2. Fears of a Shi'i Rebellion

Politics in Iraq begins with the ethno-religious divisions that define the country's three largest communities: the Twelver Shi'i Arabs, the Sunni Arabs, and the Sunni Kurds. Precise figures do not exist, but most observers estimate that Shi'is of the Twelver sect constitute a majority of Iraq's population, probably 55 to 60 percent. They live predominantly in the southern half of the country and, as a community, enjoy considerably less wealth and power than the Sunnis, who make up about 35 to 40 percent of the population. (Non-Muslims number about 5 percent.) Sunnis, in turn, divide rather evenly between Arabic and Kurdish speakers, with the Arabs living mostly in the northwest, the Kurds in the northeast. Each of these three communities has an important constituency outside Iraq: the Twelver Shi'is of Iran; the Sunni Arabs in all the Arab states; and the Kurds in Iran, Syria, Turkey, and the Soviet Union.

Today, as at all times since the sixteenth century, Sunni Arabs dominate Iraqi politics. Although they constitute only one-fifth of the population, they have maintained a hold on power through all the changes in government. Sunnis ruled when Iraq was an Ottoman province, a British mandate, an independent monarchy, and a socialist republic. The Ba'th party's secular ideology did not affect the communal distribution of power; although the Sunni grip relaxed slightly when the Ba'thists first came to power in 1963, it was reasserted by 1968. Subsequently, the Sunni domination became more complete than ever before; by the mid-1970s, much of the top political and military leadership came from a single Sunni town, Takrit.

As minority rulers, the Sunni Arabs are obsessed with the prospect of losing power to the Shi'is. (Kurdish rebels merely seek autonomy and thus pose less of a threat.) Most Iraqi government actions should be viewed in light of this concern, from its aggressive foreign policy to its extreme emphasis on pan-Arabism. Pan-Arabism helps Sunni Arabs retain power by allying them with other Sunni Arab states, and by imbuing their role with ideological legitimacy. Also, since neither Kurds nor Shi'a care much for the principal goal of pan-Arabism - that of unifying all the Arabs (why would either group want to submerge itself in a sea of Sunni Arabs?) - the incessant repetition of pan-Arabist goals serves as an effective means to exclude them from political power.

Ayatollah Khomeini's 1979 rise to power in Iran made the Iraqi Sunni leadership's long-standing concern with the Shi'a population newly urgent. Khomeini demonstrated the fundamentalist Muslim's characteristic concern for fellow Muslims in other countries. For some months at least, he seemed to command a moral influence far beyond the boundaries of Iran, as Muslim rulers everywhere worried that he might inspire other Iranian-style revolts against themselves. Memories of the Middle East's last charismatic ruler, Gamal Abdel Nasser, rushed back. Kings and presidents feared that Khomeini's brand of Islam would touch the masses as had Abdel Nasser's Pan-Arabism.

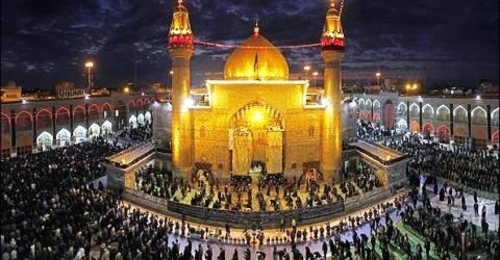

To understand Khomeini's appeal, see him as a pious Muslim might. Khomeini gained eminence as a scholar and a legal authority long before his political involvement late in life. In 1963 he joined the anti-government demonstrations in Qom and had to leave Iran the next year as a result, moving to Najaf, a Shi'i holy city in southern Iraq. From Najaf, Khomeini established himself as Pahlavi regime's most outspoken and extreme critic. Living piously in modest surroundings, preaching Islamic virtues, uninterested in the modern world, he presented a picture exactly opposite to the martial glitter of the Westernized shah. As the shah's power crumbled, Muslims witnessed an old man living a simple and familiar way defeat an oil billionaire whose vast military forces enjoyed the backing of both superpowers.

Masjid al-Imam Ali in Najaf, a leading Shi'i shrine. |

Khomeini wasted little time in extending his influence outside Iran. Even before coming to power, his influence impelled Shahpur Bakhtiar to terminate Iranian oil sales to Israel. A weak financial and political base prevented him from taking direct action in most cases, but Khomeini cut trade with the Philippines, where the state was at war with Muslims. He then allowed some volunteers to depart for Lebanon to take up arms against Israel.

But Khomeini's influence was primarily rhetorical, as was illustrated one day after the attack on Mecca's Great Mosque on Nov. 20. 1979. Iranian radio quoted Khomeini to the effect that it was "not farfetched" to assume that the attack had been "perpetrated by the criminal American imperialism." On Nov. 24, he accused the United States "and its corrupt colony, Israel," of "attempting to occupy" the Great Mosque, and called on Muslims to "rise up and defend Islam." These statements inspired demonstrations and rioting against U.S. diplomatic buildings all across the Eastern Hemisphere: in the Philippines, Thailand, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Turkey, and Libya. In the most serious case, that of Pakistan, several lives were lost and a hundred more seriously endangered; in Libya, the government of Colonel Mu'ammar al-Qadhdhafi apparently approved the attack that heavily damaged the U.S. embassy in Tripoli.

While Khomeini affected Muslims in many countries, his greatest efforts were directed toward Iraq, an area of special concern to him, owing to its proximity, its downtrodden majority of Twelver Shi'is (many of Iranian origin), and his own long residence there. Shi'is had occasionally contested Sunni supremacy in Iraq, but with little success. Lacking an organization and a spokesman, they failed to make the weight of their numbers felt. Unlike previous Shi'i leaders of Iran, Khomeini took an active interest in his co-sectarians across the border. Further, he had an ideology to offer them, a populist doctrine of Islam aimed at stirring up the oppressed and quiescent masses. Khomeini's message exactly fit the needs of Iraqi Shi'is, and having lived among them for fourteen years, he knew them first hand. No doubt, too, the humiliating expulsion from Iraq at a critical moment in late 1978 caused Khomeini, a vindictive man, to hunger for revenge against the Ba'th regime.

Relations with Iraq were bad from the very beginning of Khomeini's rule. His agents helped finance Ad-Daniel'wa, the principal Shi'i organization of Iraq. Tehran radio urged Iraqi Shi'is to resist the government. By mid-1980, officials in Baghdad were convinced that Iranian operators in Iraq's main Shi'i cities (Basra, Najaf, Karbala', and Kufa) stood behind the thousands of Shi'is who took the streets carrying huge pictures of Khomeini and their own religious leaders. Violent attacks on Ba'th officers in Iraq were also ascribed to Iranian efforts.

Several incidents caused Iraqi-Iranian relations to plummet during April 1980. On the first of that month, an Iranian threw a hand grenade, wounding Tariq Aziz, a deputy premier of Iraq, and two students; a second bomb followed a few days later. On April 6, Iraq cabled U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim to demand that Iran pull back from the Persian Gulf islands it had occupied in 1971; Iran responded by placing its border troops on full alert. Verbal fireworks followed. Khomeini called on the people of Iraq to bring down their government: "Wake up and topple this corrupt regime in your Islamic country before it is too late." He advised the army "not to obey the orders of the foes of the Qur'an and Islam, but join the people." President Husayn responded: "Anyone who tries to put his hand on Iraq will have his hand cut off without hesitation." Khomeini retorted that he hoped the Iraqi regime would be "dispatched to the refuse bin of history."

A few days later, according to Khomeini, the leader of Iraq's Shi'is, Ayatollah Muhammad al-Baqr as-Sadr, was executed by the Iraqi government. In retaliation, Khomeini called on "the noble people of Iraq" to rid themselves of Ba'th party rule. On April 23, he called on government employees to "throw in their lot with the Iraqi people in an effort to do away with the usurping Ba'th government." Many Iranian leaders joined Khomeini in making a host of incendiary statements about the rulers in Baghdad. An Iraqi role was widely suspected when Arabs from the Iranian province of Khuzistan seized Iran's embassy in London on April 30.

Iranian officials continued the verbal threats to Iraq. In August 1980, for example, President Abolhasan Bani Sadr told a Lebanese newspaper: "Orders have been issued to the Iranian armed forces not to give way to the enemy at any place. ... The rulers of Iraq should realize that henceforth we shall not be spectators nor shall we wait. We shall take the initiative to hit them and to destroy their positions and installations."

The weakness of Ba'th rule, the volatility of Iraqi Shi'is, and Khomeini's intentions convinced some observers that fear of Khomeini prompted Iraq's leaders to make war. According to this reasoning, Saddam Husayn hoped that by seizing Iranian territory and aiding rebels there, Iraqi attacks would lead to the overthrow of the mullahs. In the view of one dissident Ba'thist in exile, "the only reason Iraq went to war against Iran was to topple Khomeini. Never in the 12-year history of the Baath regime in Iraq has the rule of Saddam Husayn come under such a threat as it did since Khomeini came to power." Hanna Batatu agrees: "the outbreak of the Iraq-Iran war ... was intimately related to Shi'a unrest." Eric Davis draws an even more ominous picture: "While there were many reasons for Iraq's invasion of Iran, the key motivation was the fear than an international Shia consciousness would develop, extending from Iran through Iraq and into Syria and Lebanon."

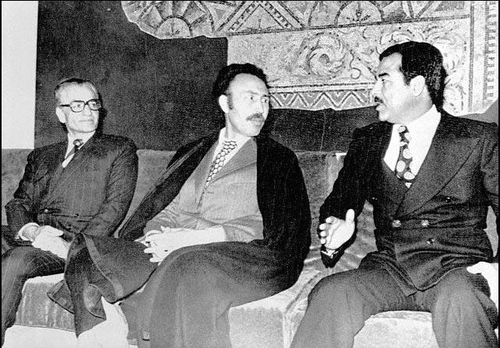

Saddam Hussein (L) and Ayatollah Khomeini. |

Second, if concern about Shi'is had paramount importance, the Iraqi government would not have launched the war from the most heavily Shi'a portion of Iraq, the south. The two countries share a border extending some 920 miles, and it was not necessary to attack across the Shatt al-'Arab. Third, a more northerly route would have struck closer to Tehran, improving Baghdad's chances of toppling the regime. As it was, Iraqi troops made no move in the direction of the capital.

Fourth, had Shi'is been the first concern, the Iraqi government would not have attacked Iranian civilians with such brutality. The Iraqi army did not fight a clean war; for months it lobbed shells across the battle lines, indiscriminately killing civilians. Worse yet, its jets attacked cities right from the beginning of the war.

The frequently repeated assumption that the Ba'thists, fearing Tehran's influence over Iraqi Shi'is, hoped to bring down the Khomeini regime does not accord with their actual conduct of the war. Rather, Iraqi military action suggests Baghdad expected to withstand Iranian influence over half its population. It surely hoped to finish the fighting so quickly that the Shi'is would have no chance to respond; and if the fighting did drag on, the government must have decided it could withstand Shi'a discontent. If so, it was proved right, for no major problems with Shi'is arose during the hostilities. If Baghdad did worry about Iranian influence over its Shi'is, this played a minor, perhaps negligible, role in causing the war.

Neither accumulated antagonisms nor fear of a Shi'a rebellion led Baghdad to make war in 1980. The primary causes of the war must be looked for elsewhere, in the boundary issues between the two countries.

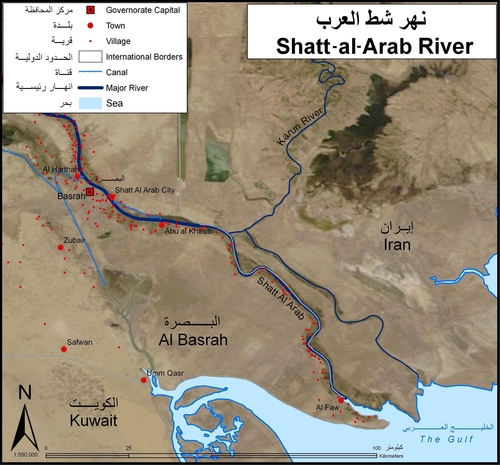

3. The Shatt al-'Arab and other Territorial Disputes

The foremost geographic disagreement between Iraq and Iran involved the Shatt al-'Arab River (Persian: Arvand Rud); other disputed territory included the three islands near the Hormuz Strait, the headwaters of rivers arising in Iran and flowing into Iraq, and the province of Khuzistan. These areas had profound economic and military importance for both countries; the stakes included maritime access, oil rights, water sources, and strategic positioning.

Indeed, the origins of today's problems go back to the early sixteenth century; a review of this controversy clarifies why the issue remains so contentious today. In brief, Iraq wants the whole river and Iran demands half of it. Each side has a wealth of legal, geographic, and historical arguments with which to back up its claims. The Shatt's history as a border falls into two broad periods: the imperial (1514-1920) and the independent (1920 to the present).

The Imperial Period. The modern state of Iraq did not come into existence until 1920; before then, it had been ruled as three provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Based in Istanbul, the Ottoman rulers viewed Iraq primarily as a buffer protecting their Anatolian heartland from Iranian incursions. The Ottoman conquest of Iraq began in 1514 and ended in 1535 with the capture of Baghdad. At the conclusion of this war, the Ottomans signed a peace treaty with the Safavid government of Iran in which the Safavids recognized the Ottoman victories. War between these two empires resumed often during the next century, usually followed by treaties. They signed treaties in 1555, 1568, 1590, 1613, and 1618.

In 1639 a treaty for the first time laid down a frontier. The Ottomans unilaterally declared what was theirs and what was Iran's, and the Safavids accepted these terms. The treaty specified the names of towns belonging to one ruler or the other. For example, it read in part: "The fortress of Zindir, which lies on top of the mountain, shall be demolished; the [Ottoman] sultan will take possession of the villages lying westward of it, and the [Safavid] shah will take possession of those lying eastward." It did not mention the Shatt al-'Arab (see Map 1.1). According to Alexander Melamid, this treaty created "a vague border resembling a broad zone... generally over a hundred miles wide [where] neither empire exercised much jurisdiction." But, however vague, the treaty lasted without major changes for 200 years and served as the foundation for all future boundary discussions.

A long peace followed, disrupted by hostilities from 1722 to 1746. Again, numerous rounds of fighting concluded with treaties (in 1724, 1727, 1732, and 1736); the final treaty of 1746 did little more than confirm the 1639 boundaries. A second long era of peace followed, broken by war in 1821-23. The First Treaty of Erzurum, in 1823, confirmed the 1746 treaty. Twenty years later, hostile incidents between the two countries brought them to the verge of war; but this time, alarmed by the prospect of still more fighting, two European powers, Russia and Great Britain, offered to mediate, thus changing the complexion of the negotiations.

Russian conquest in the Caucasus and British control of India had given these two powers a direct interest in Ottoman and Iranian affairs. Despite their rivalry, both powers found it advantageous to settle the Ottoman-Iranian boundary. Russia hoped to build a road from its territories to Baghdad and needed a clearly defined boundary; Britain wanted to regularize the legal status of the Shatt al-'Arab before setting up a steamship company there.

Ottoman and Iranian leaders had little choice but to accept the powers' offer of mediation, and in 1843 delegates from all four countries met in the Anatolian town of Erzurum. Four years of stormy meetings and no end of haggling finally produced in 1847 the Second Treaty of Erzurum, which confirmed the first treaty and made some adjustments: Iran ceded its claims to the Kurdish region of al-Sulaymaniya and in return acquired new territory and rights in the Shatt al-'Arab area. The 1847 agreement was particularly important because it dealt with the Shatt al-'Arab in detail and because it authorized a commission to delimit the border on the ground.

In light of subsequent arguments, it is striking that the 1847 accords never dealt with control over the Shatt itself, only with the lands on its eastern bank. The river was then under Ottoman control, and the treaty assumed this would remain unchanged; the accords dealt with Ottoman possessions on the eastern bank and Iranian rights of navigation and anchorage. The key passage reads:

The Ottoman Government formally recognizes the unrestricted sovereignty of the Persian Government over the port and city of Muhammara [now called Khorramshahr], the island of Khizr [now called Abadan Island], the anchorage [at Khorramshahr], and the land on the eastern bank, that is to say, the left bank of the Shatt al-'Arab.

In an explanatory note addressed to the Ottomans in April 1847 and not seen by the Iranians until January 1848, the Russian and British governments note that by anchorage at Khorramshahr they meant anchorage in the Karun River just above its confluence with the Shatt, and not in the Shatt itself.

"As a result of this detailed definition," Melamid writes, Ottoman "territorial waters in fact extended only to the western banks of Iranian islands except where there are no islands, as for example near Khorramshahr." Prior to the 1847 treaty, the Ottomans had controlled some areas on the eastern shore, but these were now ceded to Iran. In addition, Iranian vessels gained "the right to navigate freely without let or hindrance on the Shatt al-'Arab from the mouth of the same to the point of contact of the frontier of the two Parties." Both sides had free use of the entire river. As hoped for, the establishment of the Shatt al-'Arab boundary did lead to steamship service on the Shatt beginning in 1861 and on the Karun River ten years later.

The delimitation commission called for by the treaty met initially in 1850 to survey the terrain and to place markers. But, in the words of a participant, a "spirit of chicane, dispute and encroachment" prevented work; then the Crimean War intervened, and the problem was put aside in favor of more urgent business. It then took 20 years just to produce a map acceptable to all four parties!

Oil later emerged as a complicating issue. British prospectors found commercial quantities in Khuzistan in 1908, placing new strains on Iran's single port at Khorramshahr, the conduit for nearly all heavy equipment entering the country and oil shipments leaving. Because Iran's anchorage was in Ottoman waters (in accordance with the April 1847 explanatory note), Ottoman inspectors and customs agents had a free hand to meddle in the Khorramshahr port; in response, the British resolved to transfer the anchorage to Iranian jurisdiction.

The Ottomans and Iranians met in 1911 to solve these boundary problems on their own, but eighteen meetings produced no results, principally because of differences over the explanatory note. At the same time, the Russian and British authorities again felt an urgent need to regularize this border: conflict between the Ottoman Empire and Iran might drag them into war at a time when they needed to cooperate against the growing German menace in Europe. In 1913 the four countries signed the Constantinople Protocol and agreed to a new delimitation commission. Concerning the Shatt al-'Arab, the protocol states: "The frontier follows the course of the Shatt al-Arab down to the sea, leaving under Ottoman sovereignty the river and all the islands in it" except for three islands (including Abadan Island) and "the modern port and anchorage of Muhammara [Khorramshahr] above and below the confluence of the river Karun." The London Declaration, signed by British and Ottoman representatives in July 1913, put it more concisely: "The frontier follows the Shatt al-Arab to the sea, leaving the river and its islands under Ottoman sovereignty" with certain noted exceptions. For the first time, Iran had won rights in the Shatt al-'Arab itself, in a small area around Khorramshahr.

To expedite the demarcation of borders, the Russian and British commissioners (both distinguished Orientalists) had the authority to arbitrate all disputes, and at long last the boundary was demarcated between January and October of 1914. After "seventy years of diplomatic pourparlers, international conferences and special commissions," the Ottoman boundary with Iran was thus finally settled. One participant called the process "a phenomenon of procrastination unparalleled in the chronicles of oriental diplomacy."

Far from settling the conflict, however, the demarcation merely specified it. One indication of the trouble to come was the fact that the Ottoman Empire, which joined the German war effort in 1914 against Russia and Britain, never ratified the protocols of 1913.

The Independent Period. Except for Great Britain, all the actors change in the second period. Russia turns into the U.S.S.R. and recedes from the scene in 1917, Iraq comes into existence in 1920, the Ottoman Empire disappears in 1924, and Reza Shah's strong new monarchy replaces generations of weak Iranian rulers in 1925. The political and economic stakes grew larger; no longer merely the end of a long and distant border, the Shatt al-'Arab became a vital passage and a focus of national passions. Both Iraq and Iran saw the Shatt as a vehicle to assert nationalist prerogatives. And the efforts of both states to build the bases of modern economic life - ports, railways, roads, oil facilities, and international trade - converged on this river.

Iraqis were satisfied with existing arrangements. Considering the Shatt al-'Arab vital to their security and well-being, they controlled the whole of it (except the far side near Khorramshahr). For the Ottomans, the Shatt al-'Arab was a remote concern; for Iraqis, it was the national life line, and they patrolled the river with new intensity. This explains some of the rising Iranian dissatisfaction with the 1914 boundary; passing through Ottoman control to get to these ports had been bad enough, but the Iraqi hold on the river in the 1920s was much tighter. And as oil became a major export commodity for Iran in the 1920s, nearly all of it went out via the Shatt al-'Arab. Khorramshahr had become Iran's largest port, enjoying river, rail, and road connections to the Iranian interior. It had grown so much that a separate oil terminal had to be developed in 1912 at Abadan, seven miles south of Khorramshahr.

The Iranians had other problems with the existing boundary. Reza Shah believed Iranian withdrawals in the south were not matched by commensurate gains in the north. He considered Iraq's complete possession of the Shatt an affront and an economic liability.

In 1920 Iraq won nominal independence though Britain, its mandatory power, remained in charge of foreign policy until 1932. Iran refused to recognize Iraq's independence as long as Baghdad denied the Iranian request to discuss changes in the Shatt al-'Arab (and other matters). In 1929 London assured Iran that the Iraqis would talk, and recognition followed, but negotiations went nowhere. Iran demanded half the river, which the Iraqis were hardly about to grant. In the meantime, Iran acquired a small navy, which flouted Iraqi regulations and provoked numerous incidents with the Basra river police.

The Iraqi government compiled a list of complaints against Iran and submitted them to the League of Nations in 1934: interference with navigation in the Shatt, setting up police posts and patrols on Iraqi territory, unlawful claims to territory in Iraq (a small strip of land called Sarkoshk), and the damming of a tributary of the Tigris, the Gunjam Cham River. In Iraqi eyes, these amounted to "persistent disregard and violation" of the boundary lines. The Iraqi government also brought up the issue of Khuzistan, claiming that Iraq had been unjustly deprived of its rightful land by the 1847 treaty, which ceded the whole eastern shore to Iran. In contrast to Iran, with a 1,200-mile coastline replete with serviceable harbors, Iraq had only one harbor on the Persian Gulf, Basra. The Ottomans had disregarded Iraqi interests and rights when they renounced all claims to Khuzistan in return for al-Sulaymaniya in 1847. At the very least, Baghdad claimed, it should control the Shatt al-'Arab entirely; to share power with Iran would be intolerable.

In reply, Tehran made several points. Referring to the treaty of 1847, it claimed not to have granted the entire Shatt al-'Arab waterway to the Ottomans. Further, it noted, river boundaries normally run along the midstream of the thalweg (the deepest part of a river), unless explicitly asserted otherwise; and the 1847 treaty did not indicate otherwise. It argued that the 1913 treaty was not binding because the Ottomans had never ratified it; and that the Iranian government had signed it under duress.

Iraq's government wanted nothing more than assurances of Iran's respect for the existing border and promises that its warships would abide by Iraqi regulations. Iranian authorities argued that the border should be redrawn down the middle of the river. These have remained, almost unchanged, the two states' positions ever since.

Soon after these debates in the League of Nations, a coup d'êtat in Iraq brought a new government to power in October 1936, one eager to make peace with Iran. In July 1937, it signed a business-like border treaty in Tehran, reaffirming the 1913 protocol (and thus the 1847, 1823, 1746, and 1639 treaties) while making one change in the Shatt al-'Arab border; for five miles around Abadan - the growing port that handled most of Iran's oil exports - the border was to follow the thalweg. This way, the Iranians could anchor ships in their own port without having to contend with Iraqi customs agents. The treaty also called for a joint commission to handle logistical matters concerning the Shatt, such as the use of toll funds, maintenance, and the like.

This 1937 agreement held for two decades, even as both countries came to depend still more on their Shatt al-'Arab ports. When the Basra oil fields began producing, the Iraqis constructed an oil terminal at Faw, right on the Persian Gulf. As Iran depended increasingly on imports, Khorramshahr became the country's principal port. The Shatt emerged in the 1950s as a subject of renewed Iranian unhappiness, but this time the arguments centered more on economics than diplomatics. Tehran complained that tolls collected by the Basra Port Authority went for expenses unrelated to the upkeep of river facilities (such as the Basra airport) and that the Authority employed only Iraqi nationals as river pilots. Iranian officials also noted that the commission called for by the 1937 treaty had not been established; they concluded that the Iraqi government had no intention of fulfilling its conditions and wanted to control the Shatt al-'Arab all on its own. In the Iranian view, this called the validity of the treaty into question.

Relations deteriorated still further in July 1958 when a bloody coup brought radical pan-Arabists to power in Baghdad. In the effort to assert their authority, the new rulers took several steps which aggravated relations with the shah. They treated badly the Iranians living in the Iraqi holy cities, unilaterally extended Iraqi territorial waters in the Persian Gulf to twelve nautical miles, and stirred up irredentist claims to Khuzistan. As usual, however, the Shatt al-'Arab caused the worst problems; Baghdad demanded in 1959 that Iran cede its roadsteads (sheltered, offshore anchorage facilities for ships) at Khorramshahr and Abadan. In effect, the Iraqi authorities tried to make the Shatt entirely Iraqi, altogether excluding an Iranian presence from the river. They even claimed Abadan for Iraq, possibly as a first step toward claiming all Khuzistan. To justify this stand, the Iraqis argued that their predecessors had signed the 1937 treaty under British pressure, making its concessions to Iran invalid. In reply, Iran claimed half the Shatt and declared that it would do anything necessary to protect its rights in the river. Border incidents followed, Iran reinforced its troops, and serious clashes were narrowly averted when each side retreated through concessionary statements.

Another crisis began in 1960 when Tehran, angered by the Basra Port Authority's exclusion of Iranian river pilots, appointed its own nationals to navigate boats going to and from Iranian harbors. In 1961 the Iraqis refused to allow them passage, causing Abadan port to shut down for nine weeks and leading to an eventual capitulation by Iran. This incident led the Iranian government to decrease its reliance on the Shatt al-'Arab by constructing a new oil terminal outside the river, on Kharg Island in the Persian Gulf. Repeated inspections by Iraq officials, causing delays and financial losses, particularly irritated the Iranians; they also resented the requirement that all ships sailing in the Shatt fly Iraqi flags.

Although the Kharg Island terminal opened in 1965, reducing the importance of Abadan port, Khorramshahr remained vital, and differences over the Shatt hovered at a dangerous level. Smarting over the Israeli victory in June 1967, Iraq pressured Iran to stop shipping oil to Israel and its Western backers through the Shatt al-'Arab, but Iran threatened to use force if Iraq interfered with its trade, and this time the Iraqis backed down.

Starting in the mid-1960s, the shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, began a massive buildup of his armed forces, and in 1969 the Nixon administration gave him a carte blanche to buy conventional weapons from the United States. Buoyed by this support and seduced by dreams of grandeur, the shah decided to make a dramatic break on the Shatt al-'Arab issue. When in early April 1969 the Iraqi leaders laid claim to the entire Shatt, the shah's government responded on April 19, 1969 by unilaterally abrogating the 1937 treaty and announcing Iran's claim to half the river. For the first time since 1639, an existing accord had been renounced, setting a dangerous precedent.

Iranians argued that Iraq had never allowed the commission called for by the 1937 treaty to form, that it had misused toll funds taken from ships bound for Iran, and that Britain had forced the treaty on Iran. (Thus, both sides claimed British pressure had compelled their predecessors to sign the 1937 treaty.) They claimed the existing border was "contrary to all international practices and principle[s] of international law relating to frontiers" because it followed the shoreline rather than the thalweg or the median. The key passage in this Iranian declaration read:

The frontier Treaty of 1937, between Iran and Iraq, has been violated by Iraq, and as far as the Imperial Government of Iran is concerned, it has become worthless, and null and void. Further, the Imperial Government of Iran does not recognize and accept along the length of the Shatt al-'Arab any other principle but that which is internationally recognized, i.e. the Thalweg Principle, or the Median Line. It will therefore resist with all its might any encroachment upon its sovereignty in the Shatt al-'Arab and will not allow any aggression there.

Tehran enlarged its forces and laid mines. On Apr. 22, 1969, an Iranian ship entered the waterway with a military escort heading for Iranian ports and paid no tolls to Iraq. Baghdad, of course, refused to accept this unilateral abrogation. It offered to negotiate only if Iran would withdraw its forces and desist from claiming Iraqi territory. This crisis occurred at a time when many Iraqi troops served in Jordan on the Israeli front, and this further aroused Iraqi anger. Baghdad replied with small retaliations: demonstrations, with support for the Front for the Liberation of Khuzistan, subversion, and a war of words. Perhaps most serious, life became difficult for the many thousands of Iranians living in Iraq's Shi'a holy cities (especially Najaf and Karbala). By March 1972, the Iranian government counted 73,637 Iranians expelled from Iraq.

Tehran supported its claim to the Shatt by providing massive assistance to the Kurdish rebels seeking autonomy in northeastern Iraq. This tactic tied down the Iraqi army in a cruel civil war, draining the treasury and distracting the politicians. The shah indicated repeatedly that he would continue to supply the Kurds so long as his claims in the Shatt al-'Arab went unrecognized.

Iraq's weakness and isolation eventually forced the government to accommodate the shah. On Oct. 7, 1973, one day after the Yom Kippur war broke out, Iraq proposed the reestablishment of diplomatic relations. Iran accepted and, in May 1974, the two countries set up a mixed commission to delimit the boundary and arrange for troop withdrawals. Several rounds of negotiations followed, seemingly without results.

In thus came as a complete surprise on Mar. 6. 1975, at the end of an OPEC summit conference in Algiers, when Houari Boumiedienne, the Algerian president, told the assembly: "I have the pleasure to announce to you that a total accord was reached yesterday to end the differences between two fraternal countries, Iran and Iraq." The first article of this agreement reaffirmed the 1913 and 1914 protocols for the land border. The second made a critical change in the water border: the thalweg replaced the eastern shoreline as the boundary for the whole length of the disputed area, thus granting Iran its long-sought claim to half the river. In return, Iran promised, in the third article, to respect Iraq's security - meaning it would end its aid to the Kurdish rebels, whose insurrection promptly collapsed. A commission was set up to implement the agreement and to run river affairs for the two countries.

Announcing the 1975 Algiers Accord: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran (L), Houari Boumediène of Algeria, and Saddam Hussein of Iraq. |

And so they did. Watching the decline of Iran's military forces, dissension among the minorities, and growing dissatisfaction with the rule of the mullahs, Saddam Husayn renounced the 1975 treaty on Oct. 30, 1979. During the next two weeks, at Iraq's embassy in Tehran and its consulate in Kermanshah, diplomatic incidents occurred, but matters remained unchanged in the Shatt al-'Arab itself, where Iraq did not challenge Iranian control over half the river. A year later, on Sep. 17, 1980, Saddam Husayn again announced that Iraq had terminated the 1975 Algiers Agreement, saying that Iran had "refused to abide by it" and calling the Shatt "totally Iraqi and totally Arab." Coming after two weeks of border fighting and accompanied by Iraqi efforts to control the entire Shatt, this abrogation led to full-scale war. On Sep. 23, Iraq announced three territorial conditions for ending the war, beginning with Iranian recognition of Iraqi claims to the entire Shatt al-'Arab waterway.

The Shatt has long been a contentious border, but until 1969 the two sides managed to settle their differences peacefully. The shah heightened the dispute in that year when he provided military help to the Kurdish rebels in Iraq, and Saddam Husayn further raised the level of violence in 1980 when he went to war over the river. This trend will probably continue: the Shatt has steadily increased in stature as an economic asset and a point of national pride. There is every reason to expect this dual importance to grow further, making the Shatt al-'Arab a focus of strife for years to come.

The greater meaning of all these centuries of to and fro over the Shatt lies not so much in the details - most of which have been omitted here for the sake of brevity - but in the long record of concentrating on the Shatt al-'Arab as a vital area. This river is unique in the Middle East; no other boundary has a record so long and so emotional. Virtually all other borders were drawn by colonial administrators in the twentieth century. While it has become a matter of national pride to maintain those borders, they are not invested with long histories. In contrast, the boundary between Iraq and Iran had two centuries of dispute even before they European powers became involved.

The Shatt al-'Arab dispute alone was serious enough to induce either party to go to war. The legacy of centuries, the vital interests, and the national pride involved all ensure its importance. Even if Iraq and Iran were homogeneous, and even if Iraq had no Shi'a problem, the Shatt al-'Arab issue would have sufficed to cause war to break out in 1980. The territorial explanation acquires added weight when several other geographic controversies are taken into account.

Other Disputes. Baghdad's key statement of Sep. 23, 1980 mentioned the need to resolve two territorial differences with Iran in addition to the Shatt al-'Arab: three Persian Gulf islands seized by Iran in 1971 and water rights to rivers arising in Iran and flowing into Iraq. These issues, as well as differing plans for the future of Khuzistan, also contributed to the outbreak of war in 1980.

Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs are three tiny and uninhabited islands close to the Strait of Hormuz. Though without value in themselves, they have supreme strategic value and offer potentially lucrative offshore drilling rights for oil. The islands belonged to the Trucial States (now called the United Arab Emirates, or UAE) as long as the British maintained a presence in the Persian Gulf. But on Nov. 30, 1971, just one day before the British pulled out of Trucial Oman, the shah sent forces to occupy those islands, claiming that as successor to Britain in the role of protector of the gulf, he had to control the islands. (One might wonder along with J.B. Kelly, "why or how the passage of shipping would be endangered by the islands remaining in Arab hands - or, conversely, be safeguarded by their being transferred to Persia.")

While ostensibly undertaking this effort on behalf of the "Arab nation" in general and the UAE in particular, there is every reason to suppose that once the islands came under Iraqi control they would remain there. Baghdad would no doubt note how much better it could protect the islands than the UAE (just as the Khomeini regime refused to let the islands go on the grounds that Iraq would turn them over to the United States). Possession of Abu Musa and the Tunbs would greatly enhance Iraq's naval presence in the Persian Gulf and improve its claims to offshore oil reserves. These islands promise to remain an issue in the years to come.

The battle over the headwaters of rivers arising in Iran and draining into the Tigris - hundreds of miles to the north of the Persian Gulf - is often forgotten. Nearly 30 rivers begin in Iran's mountains and flow into Iraq, a sure recipe for confrontation. Water use is not regulated; the many accords going back to 1639 neither discuss the apportionment of water nor ensure the rights of existing users (with one exception: the waters of a small stream, Gangir, were divided evenly in 1914, but even this lacks a mechanism for distributing the water.) The lack of agreement means, according to Vahe Sevin, that "increased withdrawal of water across the border, particularly during the low-water period of the streams, is carried out without consideration of the consequences of such action to the areas on the other side of the boundary line." In 1959, Iran diverted one of these rivers for its own use without asking Iraq's permission; acute shortages in the neighboring Iraqi provinces resulted, followed by belligerent diplomatic relations.

Initial hostilities in September 1980 involved these headwaters. On Sep. 2, clashes began near the town of Qasr-e-Shirin; the next day, Iraq shelled it and two nearby towns. Fighting in the north continued to predominate until Sep. 17, when President Husayn announced Iraq's claim to the whole Shatt al-'Arab; at this point, attention shifted to the south. A U.S. correspondent visited Qasr-e-Shirin in June 1981 and found the once-thriving town of 50,000 Iranians bereft of civilians and occupied by Iraqi troops who had demolished the town, apparently by hand, and dug themselves in for a long stay.

Khuzistan plays a different role in the hostilities, for Baghdad did not make control of this province one of its stated goals. Nonetheless, Iraqi leaders surely aspire to conquer it. Iraq has some claim to it and would profit enormously from its possession. Three potential gains stand out.

First, Khuzistan's population has historically been about 80 percent Arabic speaking and thus appears to Ba'thists as part of the "Arab nation"; it used to be known as 'Arabistan, "land of the Arabs" (and still is in Iraq). The area had been under Ottoman rule or enjoyed autonomy for centuries before it fell under the control of Iran's central government in 1924. It would be a supreme triumph of pan-Arabism to win this land for the Arabs; such an achievement would catapult Iraq to the political leadership of the Arab world.

Second, Khuzistan contains nearly all of Iran's oil. Wining control of the province would in one blow add hugely to Iraq's oil reserves while detracting from Iran's.

Third, control of Khuzistan would end Iraq's vexing lack of Persian Gulf shoreline. At present, Iraq holds only about 40 miles of coast, most of it unusable, and its ships have to pass extremely close to Iran and Kuwait. Taking Khuzistan world free Iraq from these limitations and strengthen its naval power in the Persian Gulf, especially since the Khuzistan ports (Khorramshahr, Abadan, and Bandar-e-Shahpur - now called Bandar-e-Khomeini) are well developed. Iran's remaining coastline, though long, would include few facilities and are far from population centers. Even if taking Khuzistan is only a remote possibility, then, the possible advantages to Iraq are so great that they surely must have entered into Baghdad's calculations and must have added importantly to the other reasons for going to war in September 1980.

Conclusion: Geography and Economics

The Islamic nature of Iran's revolution caught foreign observers off guard. Who in the late twentieth century would expect that a doctrinaire religious leader calling for a return to old laws could captivate the citizens of Iran and become undisputed ruler by popular acclaim? This single event devastated modernization theory (that is, the notion that the whole world must follow the Western path to modernity) and made a mockery of the idea that Iran had become Westernized during the shah's reign. Hardheaded analysts who had long neglected Iran's cultural and religious factors were unable to account for Khomeini's dramatic repudiation of Western goals or his insistence on remolding Iran along age-old Islamic lines. While some writers continued to discount the role of religion even after the revolution, most recognized their earlier mistake in ignoring Islam. Indeed, since the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini, Westerners have tended to overemphasize Islam. Edward Mortimer notes that "where before Islam was largely ignored, now it is seen everywhere, even where it has no particular relevance."

Burned once, analysts applied their newly acquired sensibility to the Persian Gulf's next crisis - the war between Iraq and Iran - seeing this primarily in terms of cultural antagonism, religious differences, and communal fears. While such factors did in some way contribute to a hostile mood, ascription of the war to these hazy antagonisms misses its immediate and direct causes. This time - perversely - a proper understanding of events in the Persian Gulf does not require an appreciation for religion and ethnic divisions but, rather, an appreciation for geography and economics. Iraq launched the war to win full control of the Shatt al-'Arab River and to gain the many benefits of ruling additional territory.

Mar. 21, 1994 update: For a bibliography of my writings on Iran and Turkey, click here.

Jan. 7, 2010 update: Much has changed over the 27 years since this article first appeaed, but the Iraq-Iran border remains a source of dispute. From an article today, "Iran foreign minister in Iraq over border dispute":

Iranian troops have been stationed near Iraq's al-Fakkah oil field along the two countries' disputed border since Dec. 17. Iraqis in several cities have held demonstrations demanding their government take action.

Iraqi Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zebari said the two countries will begin three weeks of bilateral meetings aimed at resolving the dispute. "We have agreed to normalize the border situation between the two countries and return to the situation as it was before," Zebari told a joint news conference with Manouchehr Mottaki, his Iranian counterpart. Zebari said Mottaki's visit was an "indication that there is an honest desire to find solutions to the border dispute."

Mottaki said the Iranian leadership was "willing and determined to solve the border dispute." ...

Many Iraqis remain highly suspicious of the intentions of their volatile neighbor.