American Confusion

When U.S. Navy jet fighters attacked Syrian positions in Lebanon in December 1983, they did so because these positions were deemed intolerable to vital American interests. But just seven months later Assistant Secretary of State Richard Murphy was condoning the Syrian military presence in Lebanon, testifying before Congress that the U.S. government considered Damascus to be a "helpful player" there.

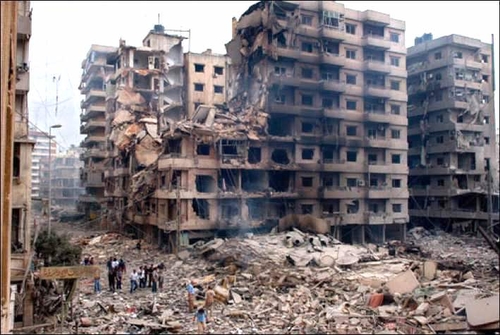

A similar reversal took place concerning the question of Syrian involvement in terrorism. Top officials had reached complete agreement that Syria had a major role in the October 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger accused the Syrian government of "sponsorship and knowledge and authority" for this crime, and Secretary of State George P. Shultz said that "Syria must bear a share of responsibility." President Reagan stated that Syria "facilitates and supplies instruments for terrorist attacks on the people of Lebanon." But a year and a half later, in gratitude for help with the release of American hostages from TWA flight 847, President Reagan conspicuously omitted Syria from a speech about state-sponsored terrorism.

What was left after the October 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine Barracks in Beirut. |

In May of this year, the same pattern emerged again. One day after Deputy Secretary of State John C. Whitehead acknowledged that the United States "has no reason to doubt" Syrian responsibility for an attempt to bomb an El Al plane leaving London, a White House spokesman called this a "premature" conclusion.

The fact that Syria is seen in so inconsistent a manner reflects the odd place of the Middle East in American politics. Americans know that North Korea sides with the Soviet Union and South Korea with the United States, that East and West Germany fit the same pattern, as do Vietnam and Thailand, Nicaragua and El Salvador. Most great power alignments are not in dispute; Americans usually understand who is the foe and who the friend.

But not in the Middle East. There the basic question of who is on what side is constantly being argued. Is Jordan a friend of the United States or not? Does Kuwait represent American interests? How close is Algeria, North Yemen, or Iran to the Soviet Union? Middle Eastern states seem to exist, politically, outside the terms of the U.S.-Soviet rivalry.

What makes the region even more eccentric is the fact that the lines of the American debate cut across the normal liberal and conservative positions. Both Saudi Arabia and Israel, for example, attract support from all areas of the U.S. political spectrum. To make matters even more confusing, liberals not infrequently adopt a conservative position on Middle East issues (as in the case of liberal Congressmen who vote against arms sales except to Israel), and vice versa (as in the case of conservatives who advocate supporting every close ally except Israel).

These inconsistencies result from the fact that U.S. discussion about the Middle East is bound almost exclusively to regional considerations. Where a state such as Egypt stands on the great issues of our time is obscured by the salience of its relationship with Israel. Financial interests (especially oil), religious concerns, and an obsession with the Arab-Israeli conflict drive the debate. Rarely does one hear about such issues as freedom of speech, democracy, or other of the larger principles of American foreign policy. As a result, American views toward the Middle East develop in an ideological vacuum.*

This same inconsistency applies to Syria, the state that has emerged in recent years as the focus of Middle East activity. The regime of Hafez al-Assad occupies an uncertain place in American eyes. Even the markedly conservative Reagan administration has reached no clear position, for example, on the nature of Syrian relations with the USSR or the proper U.S. response to them. This explains why high-level officials within the government have a tendency to change their minds and even contradict themselves about Syria. And it points to the need for a closer look at where Syria does stand in international politics - a question that turns out upon inspection to have a strikingly clear answer.

Alliance with the Soviet Union

Let us begin with the issue of Syrian relations with the Soviet Union. Syrian leaders themselves avow that the grounds of their agreement with the USSR extend far beyond the conflict with Israel. As a Syrian newspaper commentary noted in 1980, the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation which has anchored the two governments' recent relationship has created a "strategic alliance between the two great forces of socialism and national liberation." So close are Syrian-Soviet ties that other commentaries call them "a bright point in the region's sky" and "an example to be emulated in relations among countries."

All smiles: Leonid Brezhnev (L) and Hafez al-Assad. |

Syrian leaders consistently and closely identify with Soviet goals. Syria is one of very few states that freely chose to vote at the United Nations in favor of Soviet troops in Afghanistan; more generally, it has concurred with the USSR on every significant issue facing the General Assembly in recent years. By contrast, Syria has termed NATO maneuvers in the Mediterranean "provocative" and has seen them as preparations for "war and aggression."

Syria supports all the causes of the Soviet bloc. Two small examples: not long ago, a high-ranking North Korean official brought a message from Kim Il-Sung thanking Syria for its "constant support for the Korean people's just struggle to reunite their homeland." An August 1985 cable from Assad to Fidel Castro on the 20th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Syria and Cuba praised the two countries' friendship as beneficial "for the two peoples in their joint struggle against world imperialism and its allies." A telegram from the Syrian foreign minister on the same occasion expressed "Syria's admiration for the fraternal Cuban people's great achievements and their firm stands against imperialist aggression on the Latin American people."

In turn, Syria's cause receives support from the whole Soviet bloc, worded in each case almost identically. During the missile crisis of 1981, when an appeal went out from Damascus to "world Communist and labor parties and progressive forces" to denounce American plans of hegemony and Israeli aggression, those appealed to responded resoundingly and univocally.

Visits, delegations, and agreements are by no means restricted to the USSR. To take a single month as an example, during October 1983 one cooperative agreement was signed by Syria with each of Bulgaria, Hungary, East Germany, and Poland, and two with Romania. Five delegations were exchanged: North Koreans, Poles, and two groups of Soviets to Syria, Syrians to East Germany. Five publicized high-level visits took place, including trips by the Soviet chief of staff to Damascus and by Assad to Moscow.

Mongolians, Bulgarians, Cambodians, Angolans - the whole range of the Communist international - have visited the Assad government. Grenada's Communist politicians during their brief rule found time to get to Syria; on leaving, they affirmed that Syria's "courageous stand" against imperialism was backed by "all the world's progressive forces." Babrak Karmal of Afghanistan missed no occasion when he was in power to send fraternal greetings to the Syrian masses.

Even Communist parties in the opposition, such as those of Greece, Italy, and Chile, show up in Damascus, where they are sure to find a glad hand and a night's lodging. In return, Syrian representatives attend Communist party congresses in Vietnam and elsewhere. In the Middle East, Communist parties such as those of Saudi Arabia and Iraq are closely aligned with Damascus. (Nearly all Middle East countries ban and persecute the Communist party, but in Syria the party is an element in the ruling coalition.)

Syria and the Soviet Union agree on most issues in the Middle East - given the obvious difference that the former has a regional perspective and the latter a global one. Both felt betrayed by Sadat, both condemn the U.S.-sponsored "peace process," both seek to destroy the pro-Western orientation of Lebanon, both want a high price for oil. The differences that do exist - over Iraq or Yasir Arafat, for instance - are considerable, but they are well within the bounds of what allies can tolerate, and far less troublesome than, say, the differences between the United States and the members of NATO. What is more important, the two countries' strategic interests coincide, for both oppose the United States and also the pro-American governments of the Middle East.

On the military level, Syria acquires over 90 percent of its weapons, some of them extremely advanced, from the Soviet Union. Its armed forces have 650 Soviet combat aircraft and nearly 4,000 tanks. SA-11's and SA-13's give Syria the most sophisticated and densest Soviet-supplied air-defense system outside the USSR. Syrian SS-21's are capable of reaching most of Israel's population centers and military installations. Delivery in 1985 of an undisclosed number of naval vessels, including patrol boats, attack submarines, and STYX and SEPAL anti-ship missiles, heralded a major Syrian naval expansion. U.S. and Israeli military intelligence predict that in the course of 1986, Syria will receive MIG-29's, the most sophisticated Soviet aircraft outside the USSR. In a very important development, Syrian technicians have recently taken full control of the SA-5 system installed by the Soviets in early 1983, though 4,000 Soviets remain to perform other tasks, more than in any other Third World country. In all, Syria has contracted for $19 billion in Soviet military hardware.

The presence of such advanced weaponry in Syria - where it is exposed to close intelligence gathering efforts by the U.S. and Israel - indicates Moscow's commitment to Syria. Soviet leaders so trust the durability of the alliance with Syria that two Syrians have recently begun training as cosmonauts; with this, Syria joins Cuba, Mongolia, Vietnam, and India in the privilege of engaging in a "fraternal" space flight.

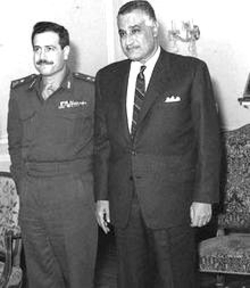

Mustafa Talas (L) with Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1969. |

In addition to this vast arsenal, Syria has also imported the Soviet military style. For over twenty years, virtually all Syrians sent abroad for military training have gone to the Soviet bloc and all foreign instructors have come from there. A Soviet-style "political department" assures ideological homogeneity among Syrian soldiers and officers. In addition to the usual army, navy, and air force, the Syrian military includes a fourth service, the Air Defense Command, patterned on the Soviet Troops of Air Defense. The command structure, which used to be patterned on that of France, now resembles that of the USSR. Some uniforms, such as army combat clothing, have been changed to resemble Soviet models.

Adopting Soviet structures means adopting Soviet methods, too; like their Soviet counterparts, the Syrian armed forces rely on centralized decision-making, numerical superiority, and offensive tactics. One demonstration of this occurred in October 1973 when, according to the authoritative World Armies, the Syrian attack on Israel "slavishly followed Soviet tactical doctrine without the resources and reserves to justify such an all-out offensive strategy, and indeed without the political need to pursue such a strategy."

In emergencies, Soviet personnel have taken over military operations within Syria. During the 1973 war, the headquarters staff of a Soviet airborne division was reportedly flown to Damascus to prepare for the defense of the city. When Syria needed military help in 1973 and 1974, Cuba provided tank operators, MIG pilots, and helicopter pilots.** Soviet pilots apparently operated a reconnaissance squadron of MIG-25's in 1976-77.

The Soviet Union also supplies Assad with internal protection. In mid-1980, at the peak of a revolt by the Muslim Brotherhood, 500 KGB advisers were located at an army base south of Damascus to train Syrian intelligence officers. Other Syrians went to the USSR for similar training. In 1982, a few days after rebellion erupted in the city of Hama, the chief of Syrian internal security, Ali Duba, requested help from the Soviets. Twelve Soviet officers, experts in street fighting, went to Hama, where three of them were killed.

Soviet Benefits

The USSR derives many benefits from its close relations with Damascus. In particular, Syria provides an eastern Mediterranean base, an air-defense link, and an agency for terrorism.

Soviet troops and equipment are both located in Syria in significant numbers. Soviet submarines operating in the Mediterranean are based primarily at Tartus, and their naval airplanes have access to the Tiyas field. SA-5's, surface-to-sea missiles, and Soviet aircraft in Syria cover significant portions of Turkey and the eastern Mediterranean, endangering the U.S. Sixth Fleet and NATO forces in those regions. Syria also offers the Soviets a pivotal location from which to involve itself in other parts of the Middle East, such as the Persian Gulf.

The air-defense network in Syria is linked electronically to stations in the USSR and to Soviet ships in the Mediterranean, making Syria an integral part of the Soviet security apparatus. The Soviets have "hands-on" control of air activity based in Syria; according to a U.S. intelligence source (quoted in the Los Angeles Times), all of the radar data, missile-readiness status, interceptor-aircraft conditions-such as fuel and armaments-and other battle information that is fed into central command posts in Syria will also be displayed for Soviet generals in the Soviet Union via space-relay transmissions."

Finally, Syria serves as perhaps the most crucial link in the Soviet Union's global network of terrorism. Almost every significant group operating in the Middle East or Western Europe has a connection to Syria, as do some groups from other regions as well. These connections are made either through the provision of training facilities or through cooperation with Libya and Iran.

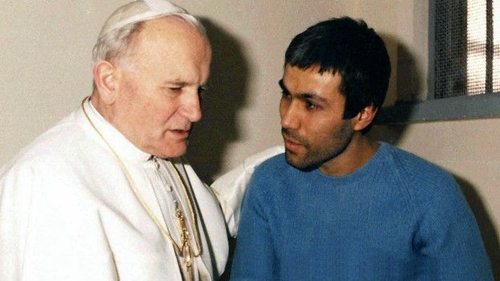

The Syrian government, which controls most of Lebanon, exploits its freedom in that country to sponsor a variety of terrorist organizations using training facilities in the Bekaa Valley. These include a large number of Palestinian groups, the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman, the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Somalia, and the Eritrean Liberation Front. Mehmet Ali Ağca, the Pope's assailant, testified at his trial in Rome that he and other members of the Grey Wolves, an extremist Turkish gang, were trained in Latakia, Syria, and taught by Bulgarian and Czech experts. Most Iranian-backed fundamentalist Muslim terrorists - whose attacks take place anywhere between Copenhagen and Kuwait - work out of Lebanon.

Mehmet Ali Ağca, would-be assassin of Pope John Paul II (L) trained in Syria. |

A number of European terrorists, including members of the Baader Meinhof gang and the Red Brigades, have spent time in Syrian-controlled Lebanese camps. Ağca has said that he trained alongside gangs from France, Italy, Germany, and Spain. Press accounts have repeatedly connected Syrian leaders with "Carlos," the phantom international terrorist. Further afield, such extremist groups as the Tamil United Liberation Front of Sri Lanka and the Moro National Liberation Front of the Philippines, have received training and aid from Syria.

To extend his reach, Assad often coordinates with Libya, Iran, or both. The two countries have a license to make mischief in Lebanon, and both sponsor organizations in collaboration with Damascus. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command, headed by Ahmed Jibril, receives support from Syria and Libya. ASALA and the Abu Nidal gang appear to receive help from all participants in this anti-American triad. Little terrorism takes place in the Middle East without some connection to Damascus; and almost all of it serves Soviet ends.

For all these reasons, the Department of Defense was right to conclude that "the Syrian-Soviet relationship remains the centerpiece of Soviet Middle East policy," and Defense Secretary Weinberger was right to call Syria "just another outpost of the Soviet Union."

Hostility Toward the United States

Another indicator of the Syrian position in international politics is its Soviet-style hostility to the United States. According to Damascus, the U.S. pursues a "general strategy of world imperialism" in a "colonialist" effort to control economic resources.*** Its goal in the Middle East is to set up military bases for two reasons: to "tighten" control over the oil regions and to threaten the Soviet Union.

Syrian media discern an American hand behind many of the region's troubles. According to them, Washington "sent the U.S. war machine to kill Palestinians and Lebanese citizens. It undertook a fascist military adventure against the Iranian revolution and then instigated Saddam's regime [in Iraq] to wage a war on its behalf against the Iranian revolution." President Assad reminds Syrians that the goal of all this is "to occupy our territory and exploit our masses,'" rendering the Arabs nothing but "puppets" and "slaves."

The United States is seen by Syria to have its own goals in the Middle East - "imperialist hegemony over the Arab homeland" - and support of Israel is regarded not as a cause but as a consequence. Israel, indeed, has no real autonomy; the U.S. can order Israel to do its bidding. Syria's prime minister says that "Israel is a U.S. base," Assad calls it an American "tool," and the newspaper Tishrin terms it the "big stick" of the United States. Israel's "expansionism" serves to soften up the Arabs, to discourage them, and render them ready to capitulate to American wishes. "It has become obvious," a Syrian daily concludes, "that the Zionist entity implements aggressive and expansionist action in the region only after total agreement with the U.S. administration." In Syrian parlance, Zionism is but a symptom of imperialism, and they are "two sides of one coin"; if the American influence in the Middle East could be eliminated, the Israeli challenge would be greatly reduced, if not ended.

Ironically, Syrian leaders understand Israel's value to the United States better than do many Americans. Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Abd al-Halim Khaddam explains: "There is a deep and organic link between the United States and Israel. We are under no illusions about this. The link is not due to the 'Zionist lobby' in the United States but to the fact that it is the only friend of the United States in the area and because it represents a major base for protecting U.S. interests." True, this formula is sometimes turned around when Syrian leaders hope to affect American policy; then they speak of a conspiracy carried out by "world Zionism." But in any case, there is no argument from Syria - as there is, say, from Saudi Arabia - that the U.S. is backing the wrong side in the Middle East.

Syrian leaders sharply disagree with those who see the main Arab problem as Zionism. "No matter how skillful Washington is in maneuvering and applying pressures, it will not succeed in convincing the Arabs that Israel [instead of the U.S.] is the one which occupies Arab territories." After the 1982 conflict in Lebanon, the Syrian prime minister stressed that "the war was not merely between Syria and Israel, but between Syria and those behind Israel." The U.S., not Israel, is the "essence of evil." Assad has been quoted as saying that "the United States is the primary enemy," and Syrian leaders imply that an agreement between Syria and Israel is ultimately impossible not because of the dispute over the Palestinians or other local issues but because of the role Israel plays as an agent for the United States.

In the Syrian view, Israel is by no means the only American lackey in the Middle East. The revolt by the Muslim Brotherhood in 1980 was similarly blamed on American agents: "The weapons are Israeli, the ammunition from Sadat, the training is Jordanian, and the moral support is from other parties well known for their loyalty to imperialism." More recently, the Syrians identified a "reactionary axis" of Arabs working for the U.S. - Yasir Arafat, Jordan, Egypt, and Iraq. To these are sometimes added Somalia, Sudan, and Oman.

The language against these purported clients can become wildly abusive, resembling Muammar al-Qaddafi's. A radio commentary of January 1981 accused "the gang of CIA agents in Amman" - i.e., the Jordanian monarchy - of foisting on Jordanian citizens "the cud of all the byproducts of the Zionist and imperialist psychological war machine." When Anwar al-Sadat was killed, Syrian radio broadcast a speech celebrating the event and calling for the death of other Arab "traitors," including King Hussein of Jordan and Saddam Hussein of Iraq.

The Arabs, according to Syria, face a stark choice: either "submit to a hostile United States or choose a strategic alliance with the friendly Soviet Union." Syrian rhetoric discounts the possibility that the Arabs can stand up to the "U.S. onslaught" alone, but Syrian leaders are proud to see themselves in the vanguard of the "struggle against U.S. domination of the Middle East," and they welcome the special American enmity that this entails. The Assad government, having rejected Camp David, is a proper object of Washington's anger: "The United States is directing all its psychological, economic, political, and diplomatic resources for war against Syria, using all its agents, hirelings, lackeys, and mercenaries."

In response, Syrian rulers from time to time explicitly threaten the United States, as when the prime minister asserted in 1980, "If I were able to strike at Washington, I would do so." A 1982 newspaper editorial called on the Arabs "to strike at every type of U.S. interest, to behead the snake." These threats are not idle. There have been repeated attacks against American soldiers and diplomats, perhaps the most spectacular being the Katyusha artillery rocket barrage in May 1983 on Secretary of State Shultz as he spent the night in the U.S. Ambassador's residence in Beirut.

A leading Syrian politician observed in 1980 that "the United States is the United States whether Carter goes or Reagan comes," while another commentary noted that "the departure of one person [as President of the U.S.] and the arrival of another will make no difference." In short, the Syrian leadership contends that its conflict with the United States results from structural reasons, and will continue indefinitely.

Aggression against Neighbors

Syria's position is reflected not only in its policy vis-a-vis the great powers, but in its behavior toward neighboring countries.

Expansionist states around the world look to the USSR for support of aggression against their neighbors, and Syria is no exception. Just as the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, so Vietnam attacked Cambodia, Libya attacked Chad, Nicaragua attacked El Salvador, North Korea has designs on South Korea - and Damascus, conforming to the pattern in spades, has hostile relations with all five of its neighbors and also aims to dominate the PLO. With regard to four of those neighbors - Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey - Syrian ambitions fit in well with Soviet policies.

The Syrian intent of "liquidating the Zionist presence" has great value to Moscow. If Assad did not keep the Arab conflict with Israel alive militarily, this might turn into a diplomatic dispute, and then the Soviet role in the Middle East would greatly diminish, for the USSR has little to offer anyone besides arms. Moscow, in other words, relies on Syrian intransigence toward Israel to maintain its place in Middle East politics.

And the Syrian government is intransigent, rejecting any accommodation to Israel's existence, either by its own citizens or by other Arabs. "The most hostile" of Israel's neighbors (according to Israel's Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin), Syria led the opposition to Egypt's peace treaty with Israel in 1979 and worked against Jordanian acceptance of the 1982 Reagan Plan. It forced the Lebanese government to abrogate the May 1983 agreement with Israel and split the PLO when Arafat showed interest in negotiations in early 1983.

Assad defines his goal as "strategic parity" with Israel, so that Syria can take on Israel in a one-to-one confrontation. Toward this end, he has increased the regular Syrian army from fewer than 300,000 troops in mid-1982 to 500,000 today, and the number of divisions from six to nine.

While this ambition is deadly serious, there is another, and usually overlooked, purpose to the Syrian military build-up. Attaining parity with Israel, the strongest state in the region, translates into decisive power over Jordan and the other Arab states, as well as the PLO. As Secretary of State Shultz recently noted in congressional testimony, "Syria holds major quantitative advantages over Jordan in personnel (5 to 1), tanks (4 to 1), armored personnel carriers (2.5 to 1), artillery (4 to 1), and combat aircraft (5 to 1)." Assad uses this strength to intimidate the Jordanian government. Syrian troops are deployed along the Jordanian border in times of crisis and sometimes sent into action. In December 1980, Syrian jets attacked locations in central Jordan with impunity. At other times, Assad provided aid to anti-government elements within Jordan, for example encouraging a group of officers in July 1985 to stage a coup d'etat.

Assad has succeeded in extending Syria's hold to most of the territory of Lebanon. This process began in the early 1970's and received a boost with the outbreak of Lebanon's civil war in 1975. In June 1976, Syrian forces entered Lebanon, establishing control over most of the country. Damascus is at present attempting to bring the remaining portions of Lebanon under its dominion.

Notwithstanding its initial opposition to Syrian expansion into Lebanon, the Soviet Union gains from it in several ways. First, this opens Lebanon to Soviet encroachment; delegations of up to a dozen Soviet military officers have been sighted as far from Syria as Shuwayr, just sixteen miles outside Beirut. Second, as has been noted, a wide range of pro-Soviet terrorist groups receive training in the regions under Syrian control, especially the Bekaa Valley. Finally, Damascus supports a coalition of pro-Soviet forces gaining power in Lebanon.

With respect to Syria's northern neighbor, Turkey, Damascus makes trouble in a number of small ways. It encourages agitation in Hatay, a province of Turkey that borders on Syria and is shown on official Syrian maps as part of Syria. The government also lays claim to other parts of Turkey. In 1980, Foreign Minister Khaddam reminded the Turks that 54,000 square miles - an area larger than England - had been "usurped" from Syria by Turkey. Syria disputes Turkey's right to control its river waters. As noted earlier, Damascus supports the terrorist Grey Wolves and ASALA, an organization that guns down Turkish diplomats around the world. All these activities threatening Turkish security are clearly welcome to the leaders of the Warsaw Pact.

By contrast, Syrian hostility toward the PLO and Iraq - which complicates Soviet diplomacy and weakens the anti-American front-must surely annoy the Soviet leaders. But even here, Syrian aggressiveness brings benefits. When Damascus calls Yasir Arafat a "deviationist" and a "U.S. tool" for even considering negotiations with Israel, this reinforces parallel Soviet pressures. So does the accusation that Arafat has fallen into "a swamp of treason [and] capitulation" and adopted "conspiratorial methods against the Palestine question." As for recent joint PLO-Jordanian diplomacy, when President Assad called Arafat and King Hussein "the staunchest agents of imperialism and Zionism," his declaration exactly fit Soviet purposes.

Domestic Sovietization

Still another indication of Syria's affinity with the Soviet Union is the nature of its internal regime. Just as the democracies are the only true, long-term allies of the United States, so the Soviet Union develops its deepest ties with totalitarian governments. That the Assad years have witnessed a turn away from authoritarianism (government control of politics) and toward totalitarianism (government control of everything) in Syria is apparent from changes that have occurred in the economic, social, and cultural realms. Although the Syrian government still lacks the all-encompassing institutions of state control of the USSR, the trend is clearly in that direction.

The Syrian economy has come increasingly under bureaucratic jurisdiction. In agriculture, the government has reduced the proportion of private farms from 82 percent in 1972 to 66 percent in 1982, while increasing the proportion of state-controlled cooperatives. In manufacturing, the state owns all of what are called "strategic industries." Besides the obvious ones, this includes such enterprises as sugar refining and wool spinning. Attendant on this have been Soviet-style inefficiency, a drop in quality, and maldistribution of goods.

Assad gains direct influence over many Syrians by having them work for him. Civilian employment by the government rose from 12 percent of total employment in 1973 to 22 percent in 1983. Growth in military employment has been even more dramatic, rising from 6 percent of adult males in 1968 to 15 percent in 1982.

As in most Soviet-bloc countries, Syria's leaders devote an extraordinary proportion of their country's resources to military strength. According to highly-placed officials, the Syrian government earmarked 60 percent of its budget for military expenditures in 1980, 70 percent in 1981, and 60 percent in 1986. Outside sources estimate this to be 30 percent of the country's GNP.

Such expenditures give the Syrian military a prominence that matches its Soviet counterpart. Its activities permeate the country's life. The military, for example, freely requisitions land and material resources, interferes in private life via the intelligence services, takes up large portions of the school day for pre-military training, and owns one-third of the motor vehicles in Syria. When we add this to the "strategic industries" and the vast resources devoted to military power, the picture emerges of a society dominated by Soviet-style militarism.

To offset the economic burden, Syria receives a large percentage of Soviet-bloc economic aid, with the USSR providing about half and the states of Eastern Europe the other half. This money mostly goes for infrastructure projects such as railroads, ports, dams, land reclamation, and oil refineries. It is spent in such a way as to assure Soviet-style control of the economy as well as dependence on Soviet parts and technicians. Over 1,000 Soviet economic advisers work in Syria. Unofficial estimates place the debt to the USSR at $14 billion.

The Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest, was built with Soviet assistance. |

Soviet-style media have emerged in Assad's Syria. Soviet movies and television programs are ubiquitous (although they never attract an audience if an alternative is available). In its official pronouncements, Damascus uses boiler-plate leftist language with the numbing regularity of all Soviet-bloc regimes. According to the World Press Encyclopedia, the Syrian press, "like the nation, speaks with one voice ... a de-facto state-mobilized press exists." The same reference work points out that the two leading papers, Ath-Thawra and Al-Baath, published respectively by the Ministry of Information and the Baath party, serve as the Izvestia and Pravda of Syria.

Foreign journalists find that, as in the Soviet bloc, citizens are afraid to talk to them about politics. But the Syrian regime has gone farther than the Soviet prototype in that it forbids Western journalists to take up residence in Syria. This means that they are prevented from cultivating personal contacts, and must rely almost entirely on official sources. Following Soviet practice, even the most innocuous military information is deemed a state secret.

The similarities to the Soviet Union do not end with this, however, but extend to the repression of citizens. Like all Soviet-bloc regimes, Syria disregards the rule of law, controls speech, persecutes religion, and engages in torture. Reports of brutality are numerous. The day after an attempt on Assad's life in July 1980, 600 to 1,000 political prisoners held in a jail in Palmyra were massacred. According to an eyewitness, the prisoners were lined up against walls and machine-gunned to death; in reward, each of the soldiers engaged in the massacre was given 100 Syrian pounds.

The regime's violence has been greatest in the city of Hama, which was three times the scene of massacres - in April 1980, April 1981, and February 1982. The last occasion was the largest-scale massacre of civilians in the Middle East in many years; 12,000 troops attacked opposition strongholds with field artillery, tanks, and air-force helicopters, killing about 24,000 citizens. In addition, 6,000 soldiers lost their lives and most of the 10,000 inhabitants of Hama who were jailed then disappeared. In all, one-tenth of Hama's population died.

Amnesty International's report on Syria in 1983 stated:

Syrian security forces have practiced systematic violations of human rights, including torture and political killings, and have been operating with impunity under the country's emergency laws. There is overwhelming evidence that thousands of Syrians not involved in violence have been harassed and wrongfully detained without chance of appeal and in some cases have been tortured; others are reported to have "disappeared" or to have been the victims of extrajudicial killings carried out by the security forces.

The U.S. Department of State concurs. Its annual review of human-rights practices regularly points to Syrian government offenses. In 1983 it reported that the authorities "pursued dissident elements, carried out cordon-and-search operations without judicial safeguards against invasion of the home, carried out arrests, in many cases causing persons to 'disappear,' and engaged in torture and other brutal practices." More recently, the State Department has noted that "while the more public forms of repression have diminished ... there have been no indications of a trend toward a more open political system or greater respect for the integrity of the person." Stalin's methods, in other words, have been replaced by Brezhnev's.

Although the Syrian government denies these accusations, it publicly celebrates brutality. For example, in October 1983 (according to a report in the Jerusalem Post),

Syrian television showed sixteen-year-old girls-trainees in the Syrian Baath party militia-fondling live snakes as President Hafez Assad and other Syrian leaders looked on approvingly. Martial music reached a crescendo as the girls suddenly bit the snakes with their teeth, repeatedly tore off flesh and spat it out as blood ran down their chins. As the leaders applauded, the girls then attached the snakes to sticks and grilled them over the fire, eating them triumphantly.

After this, militiamen "strangled puppies and drank their blood." Such demonstrations are clearly intended to send a message to the regime's domestic opponents.

These internal developments are not in themselves unusual in the Middle East or in the Third World, nor do they require close ties to the Soviet Union. But when combined with the other manifestations we have examined, they contribute in an important way to the regime's overall Soviet orientation.

Helping American Hostages: A Special Case

David S. Dodge. |

While Assad has undeniably been helpful, however, three considerations diminish the political significance of his acts. First, in many of these cases the regime played a double game. David Dodge was abducted with Syrian complicity, for how else could he have been taken from Beirut to Iran? In the effort to win release of the TWA passengers, Assad stressed his solidarity with the hostage holders ("We stand with them firmly, and they admit our support is basic"), but appealed for the release of the hostages on tactical grounds: holding the Americans was counterproductive because it might provoke the United States to a major strike in Lebanon. In the Jeremy Levin case, Damascus first said that it had won Levin's release through negotiations, only to retract this claim later when the falsehood became evident.

Second, these acts are transparent attempts to improve Assad's image. The White House had to issue a statement that the U.S. was "grateful" to Assad and his brother for their "humanitarian" efforts on David Dodge's behalf. Lieutenant Goodman was delivered to the Reverend Jesse Jackson, a presidential candidate at the time and a leading critic of the U.S. policy of confronting Syria. By getting involved in a U.S. political campaign, Assad garnered enormously favorable publicity. Though the Syrian government lied about its role in Jeremy Levin's escape, President Reagan nevertheless called Assad to express his gratitude and a State Department spokesman thanked Damascus for its "positive role" in this affair. And Syrian help with the TWA hijacking was rewarded when Reagan omitted Syria from his list of states that sponsor terrorism; as a ranking White House aide explained, "Obviously you don't return a favor with harsh language."

These efforts have had a wide effect: many Americans view the Syrian regime as one not unfriendly to the United States and very few associate it with terrorism. According to a New York Times/CBS News poll taken in February 1986, whereas 29 percent of Americans associate Libya with state-sponsored terrorism, Syria is mentioned by a mere 3 percent.

Third, Syria's promise to help gain the release of the remaining American hostages in Lebanon effectively prevents the United States from confronting Syria. David Dodge was freed just when Washington was most angry about Syrian rejection of the U.S.-arranged accord between Israel and Lebanon. Assad released Lieutenant Goodman to prevent further Navy attacks on his positions. Damascus placed itself as an intermediary between the United States and the Shiite radicals who held the TWA airliner in order to prevent an American attack. Most recently, proof of Syrian responsibility for terrorist actions in London and Berlin sparked a flurry of Syrian efforts on behalf of kidnapped Americans in Lebanon.

Syrian mediation is taken so seriously that such high-ranking officials as Vernon Walters, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, have gone to Damascus to discuss the hostages with President Assad. Whispered promises of help from Assad subvert the possibility of U.S. sanctions against Syria. (This partially explains why Libya's role in the massacres at the Rome and Vienna airports was played up, while Syria's role was ignored.)

Though certainly welcome in a small way, the help Assad provides must be seen for what it is; a public-relations gesture which at no cost to himself aims to confuse American opinion about the true relations of the two states and undercuts strong measures by the U.S. government. This minor matter should not obscure the damage Assad does to American objectives - no more than the release of Anatoly Shcharansky should alter one's understanding of Soviet goals.

Conclusion

In the end, the confusion that exists about Syria's true position has less to do with hostages than with a habit of seeing the country exclusively in terms of Middle East politics, and in particular in terms of the Arab-Israeli conflict. But once we extract Syria from the regional issues of the Middle East and view it through the prism of international relations, we see the plain truth that Syria is the leading Soviet ally and the outstanding U.S. enemy in the Middle East. It deserves to be acknowledged as such, and the knowledge deserves to be acted upon.

Daniel Pipes is director-designate of the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia and editor of Orbis. Mr. Pipes wrote this article while a visiting fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Footnotes

* I have documented this phenomenon, offered an explanation for it, and argued for its significance in "Breaking All the Rules: The Middle East in U.S. Policy," International Security, 9 (1984), pp. 124-50.

** Revealingly, the Cuban brigadier general who commanded those soldiers showed up in Nicaragua a few months ago.

*** As with all Soviet-backed regimes, the question arises as to how much the leadership believes its own rhetoric. Three observations are pertinent in this regard: constant repetition has an effect on both speaker and hearer; the rulers almost certainly feel a genuine need to justify their actions; and Damascus's behavior is consistent with these public statements.