Two patterns have shaped Israel's history since 1992 and go far to explain Israel's predicament today. First, every elected prime minister has broken his word on how he would deal with the Arabs. Second, each one of them has adopted an unexpectedly concessionary approach.

Here is one example of deception from each of the four prime ministers:

- Yitzhak Rabin promised the Israeli public immediately after winning office in June 1992 that "with the PLO as an organization, I will not negotiate." A year later, however, he did precisely that. Rabin defended dealing with Yasir Arafat by saying he had found no other Palestinians to do business with, so to "advance peace and find a solution," he had to turn to the PLO.

- Benjamin Netanyahu promised before his election in 1996 that under his leadership, Israel "will never descend from the Golan." In 1998, however, as I established in The New Republic and Bill Clinton just confirmed in his memoirs, Netanyahu changed his mind and planned to offer Damascus the entire Golan in return for a peace treaty.

- Ehud Barak flat-out promised during his May 1999 campaign a "Jerusalem, united and under our rule forever, period." In July 2000, however, at the Camp David II summit, he offered much of eastern Jerusalem to the Palestinian Authority.

- Ariel Sharon won a landslide victory in January 2003 over his Labor opponent, Amram Mitzna, who called for "evacuating the settlements from Gaza." Mr. Sharon ridiculed this approach, saying that it "would bring the terrorism centers closer to [Israel's] population centers." In December 2003, however, Mr. Sharon adopted Mitzna's unilateral withdrawal idea.

Prime ministers sometimes complain about predecessors breaking their word. Mr. Netanyahu, for example, pointed out in August 1995 that Rabin had "promised in his election campaign not to talk with the PLO, not to give up territory during this term of office, and not to establish a Palestinian state. He is breaking all these promises one by one." Of course, when he got to office, Mr. Netanyahu also broke his promises "one by one."

What prompts each of Israel's recent prime ministers to renege on his resolute intentions and instead adopt a policy of unilateral concessions?

In some cases, it is a matter of expediency, notably for Mr. Netanyahu, who believed his reelection chances improved via a deal with the Syrian government. In other cases, there are elements of duplicity – specifically, hiding planned concessions knowing their unpopularity with the voters. Yossi Beilin, one of Mr. Barak's ministers, admitted during the Camp David II summit that he and others in the government had earlier concealed their willingness to divide Jerusalem. "We didn't speak about this in the election campaign, because we knew that the public would not like it."

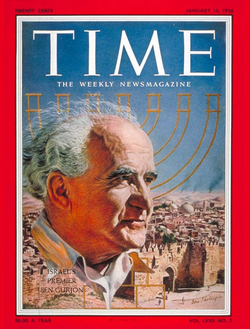

David Ben-Gurion on the cover of Time magazine, Jan. 16, 1956. |

Not for this great man is it enough to plug away at the dull, slow, expensive, and passive policy of deterrence, hoping some distant day to win Arab acceptance. His impatience invariably leads in the same direction – to move things faster, to develop solutions, and to "take chances for peace."

If the prime minister's initiative succeeds, he wins international acclaim and enters the Jewish history books [as the second Ben-Gurion]. If it fails – well, it was worth the try and his successors can clean up the mess.

Grandiosity and egoism, ultimately, explain the prime ministerial pattern of going soft. This brings to mind how, for centuries, French kings and presidents have bequeathed grand construction projects in Paris as their personal mark on history. In like spirit, Israeli prime ministers have since 1992 dreamed of bequeathing a grand diplomatic project.

The problem is, these undemocratic impulses betray the electorate, undermine faith in government, and erode Israel's position. Such negative trends will continue until Israelis elect a modest prime minister.

June 29, 2004 addenda: (1) I tried this thesis out in Jerusalem on June 21, before an audience that included Avigdor Liberman, who had just lost his job as minister of transportation in the Sharon government due to his opposition to the unilateral withdrawal from Gaza. On the conclusion of my remarks, Liberman bounded out of his seat, took the microphone from me, and announced to everyone, "When I am prime minister, I will not do that. I will stay faithful to my promises."

(2) Yitzhak Shamir's name does not appear in the above article, for he did keep his promises; he deserves honor for that. Indeed, Shamir's prime ministries, 1983–84 and 1986–1992, amounted to a golden age of Israeli politics, when an underestimated leader stood true to the voters who elected him, did not act corruptly, and did not pander.

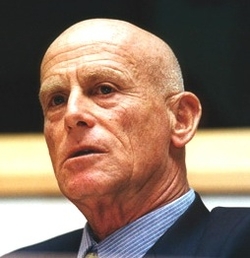

Ami Ayalon demands that Netanyahu dream big.

Feb. 20, 2013 update: Despite my apprehensions four years ago, Binyamin Netanyahu stayed respectably close to his electoral promises during his second term as prime minister, 2009-13. But his third term got off to a rocky start with the clinching of a deal yesterday with Tzipi Livnia's Hatnuah party, thereby ignoring the wishes of those who voted for him even before his new government takes office.

Mar. 25, 2013 update: Ami Ayalon, former head of Shin Bet and now a left winger, captured the burden on Israel prime ministers when he declared (as paraphrased by Ben Birnbaum in "The End of the Two-State Solution: Why the window is closing on Middle-East peace") that "Netanyahu needs to envision his grandson 40 years from now reading a newspaper about the three great Zionist leaders: Theodor Herzl, who dreamt the state; David Ben Gurion, who built it; and Benjamin Netanyahu, who secured its future as a Jewish democracy."

July 5, 2013 update: I nominate Binyamin Netanyahu today for a second inclusion in this list at "Is Netanyahu Turning Left?"

May 5, 2020 update: David Makovsky and Dennis Ross look at this same pattern and interpret not as wayward but as wise:

Israeli leaders ... often came to power late in life. Key former prime ministers knew they had little time and acted accordingly. At the end of their careers, they were willing to make difficult decisions often at odds with their traditional constituencies.

Before coming to office, Menachem Begin did not think he would yield the Sinai to Egypt, shortly after Israel just faced Egypt on the battlefield, and set a precedent of withdrawing all Sinai settlements. Before coming to office, Yitzhak Rabin (who was briefly leader when he was younger) did not think he would shake the hand of a person he and most Israelis reviled as an arch-terrorist, Yasir Arafat. Before coming to office, Ariel Sharon—the architect of the Gaza settlements while head of the IDF Southern Command in 1971—did not think he would be the one to dismantle these very communities.

They knew these moves would be unpopular but they took the step anyway because they felt the context had changed due to developments since taking office. Each believed the national interest necessitated looking at the big picture of Israel's strategic interests in the region, with the US and internationally. They defined legacy by looking at what Israel needed rather than what political constituencies wanted.

By defining legacy in a wider sense and not in terms of what gets the most votes, Begin bequeathed to Israel decades without the kind of conventional war with Arab states that was routine in the first quarter century of its existence and claimed many lives on both sides. Thanks to Rabin and Sharon, Israel has avoided constant war with the Palestinian national movement writ large, even though they clearly were not able to alter Hamas' calculus or resolve all the fundamental issues with the Palestinians more generally. All three of these leaders were also guided by the need to retain Israel's identity as a Jewish and democratic state.

Ariel Sharon was fond of saying: "what you see from here, you do not see from there." He meant that the Israeli prime minister puts the country's future on their shoulders and their perspective, by definition, is different from that of their constituents. Leadership is about doing what is right and not what is popular.

July 7, 2025 updates: Dennis Ross relates this anecdote about Benjamin Netanyahu:

Late one evening, during negotiations over the Hebron protocol in December 1996, Benjamin Netanyahu said to me out of the blue that he was going to "do what Ben-Gurion did." "You mean Begin?" I asked, thinking that he had misspoken. Menachem Begin had preceded Netanyahu as leader of the Likud party and, like Netanyahu, had originally come out of the Revisionist movement.

"No, Begin didn't do the big stuff," Netanyahu answered. "Ben-Gurion did the big stuff."