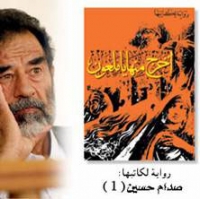

Ash-Sharq al-Awsat, a London-based Arabic paper, yesterday began the complete serialization of Saddam Hussein's final novel written as a free man, Be Gone Demons! (اخرج منها ياملعون) As though it were just any book, the newspaper posted a picture of the cover and of the author (appearing as a jailbird, however, not as absolute ruler).

The Associated Press's Salah Nasrawi helpfully provides a summary of the plot, as related to him by Ali Abdel Amir, an Iraqi writer and critic who read the whole manuscript: The novel recounts a Zionist-Christian conspiracy against Arabs and Muslims that an Arab army eventually defeats by invading the Zionist-Christian land and toppling one of its monumental towers, an apparent reference to Sept. 11, 2001.

The novel opens with a narrator, who bears a resemblance to the Jewish, Christian and Muslim patriarch Abraham, telling cousins Ezekiel, Youssef and Mahmoud that Satan lives in the ruins of a Babylon destroyed by the Persians and the Jews. ...

Ezekiel, symbolizing the Jews, is portrayed as greedy, ambitious and destructive. "Even if you seize all the property of others, you will suffer all your life," the narrator tells him. Youssef, who symbolizes the Christians, is portrayed as generous and tolerant - at least in the early passages. Mahmoud, symbolizing Muslims, emerges as the conqueror at the end of the book.

The critics have not been kind to Be Gone Demons! Saddam "was completely out of touch with actual reality, and novel writing gave him the chance to live in delusions," comments Abdel Amir. Saad Hadi, a journalist who had a hand in the production of Saddam's novels, agrees: "He lost touch with reality. He thought he was a god who could do anything, including writing novels."

According to Hadi, Saddam's favorite novelist was Ernest Hemingway, in particular The Old Man and the Sea, whose style he tried to emulate. "He'd sit in his state room and recount simple tales, while his aides recorded his words." Youssef al-Qaeed, an Egyptian novelist, describes the dictator's oeuvre as "naïve and superficial."

This is hardly Saddam's first published novel. "At the end of the year 2000, a publishing sensation left Baghdad abuzz with rumor," reports Ofra Bengio in "Saddam Husayn's Novel of Fear," an analysis of Saddam's becoming the author of a historical romance titled Zabiba and the King. Although Bengio finds the novel "boring and incoherent," she argues it "is best understood as Saddam's own preparation for his final descent from the stage. It should be read as a summary of his life, an 'artistic' contribution to his people, an epitaph, and a last will and testament, all rolled into one."

One might have thought that more pressing issues of state would have been on the absolute dictator's mind by late 2002, as the Bush administration made clear its impatience with Iraqi behavior and signaled an intent to take action. One would be wrong, at least according to an account given by NBC news on July 15, 2003: Tom Brokaw reported on the authority of Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz, already in captivity, that "in the last year Saddam Hussein has been preoccupied with writing three epic novels."

Even more remarkable is the information from a subsequent report in London's Daily Telegraph: "Saddam Hussein spent the final weeks before the war [in March 2003] writing a novel predicting that he would lead an underground resistance movement to victory over the Americans, rather than planning the defence of his regime. As the war began and Saddam went into hiding, 40,000 copies of Be Gone Demons! were rolling off the presses."

After Zabiba and the King, Saddam produced The Fortified Castle and Men and the City and finally Be Gone Demons! Tariq Aziz's comment suggests that another two novels were in the works when war so rudely interrupted.

Saddam's being caught up with novel writing as war was brewing directly confirms a thesis I presented months back, in "[Saddam's] WMD Lies," to explain the seemingly missing weapons of mass destruction. Supposing there really are no nukes in Iraq, Saddam gave off the impression he had them as a result of a terrible error.

This mistake can best be explained as the result of Saddam inhabiting the uniquely self-indulgent circumstance of the totalitarian autocrat, with its two key qualities: Hubris: The absolute ruler can do anything he wants, so he thinks himself unbounded in his power. Ignorance: The all-wise ruler brooks no contradiction, so his aides, fearing for their lives, tell him only what he wants to hear. Both these incapacities worsen with time and the tyrant becomes increasingly removed from reality. His whims, eccentricities and fantasies dominate state policy. The result is a pattern of monumental mistakes.

Saddam Hussein's being consumed with a literary urge, even as his dictatorship was about to be destroyed by the greatest power on earth, points to both his hubris and his ignorance. It also goes far to explain how he could think there were nuclear weapons in the works when they did not exist by the time his political demise began in March 2003.