Of all the territories that have been cosmopolitanized by the West, Japan is unique in giving back as much as it has received, and the West... is having some difficulties in coping with this unexpected reciprocity.-- Reyner Banham

Even as Japan becomes a world leader in modernity, two stereotypes continue to interfere with an understanding of that country.

First, there is the old canard that the Japanese can only imitate, not originate. Already in 1871, one British observer accused them of a "lack of originality" and nine years later another wrote about Japan having "a civilization without any originality." In 1900, Algernon Bertram Mitford said that "Japan has never originated anything." A few years later, Henry Norman explained that, "in commercial matters the Japanese have exhibited their imitativeness in the most extraordinary degree. Almost everything they have once bought, from beer to bayonets and from straw hats to heavy ordinance, they have since learned to make for themselves." In 1915 Thorstein Veblen held Japanese assimilation of Western ways to be "most superficial" and "has not yet had its effect on the spiritual outlook and sentimental convictions of the people."

Similar charges has been repeated many times since, and even by very knowledgeable observers. In 1971, for example, Donald Richie wrote that "in film, as in much else, Japan did not invent techniques or even styles; rather it brought those existing to a point of perfection."

The accusation is nonsense. Even the most superficial acquaintance with Japan after 1854 should be enough to recognize that the country has been enormously creative; and this is more true today than ever before. The Japanese explore modernity directly on their own, while Africans and other Asians learn about it through translations. In the rest of the non-Western world, almost all that is new is derivative; in Japan it is mostly original.

Perceptive observers have noted Japanese creativity throughout the twentieth century. Henry Dyer wrote in 1904:

The charge of want of originality on the part of the Japanese is... superficial and unfair.... In the course of little more than a generation the Japanese have shown that they are not only able to adapt Western science to Japanese conditions, but to advance its borders by original investigation.... It is too late in the day to continue to repeat what was a very common saying thirty years ago; namely that the Japanese were very clever imitators but that they had neither originality nor perseverance to accomplish anything great.

A few years later, Ernest Fenollosa observed: "We have belittled the Japanese as a nation of copyists."

The second stereotype holds that, if Japanese have any originality, it is limited to two areas - technical ingenuity and economic proficiency. Sure, the Japanese can improve what others invent; and, yes, they do work very hard, but foreigners and Japanese too tend to see the country's achievement as narrowly limited to making Sony and Toshiba into household names worldwide.

This glib generalization ignores the broad-based and profound cultural transformation that has taken place in Japan. Technical skills are just a small part of it; and economic success is only one of many accomplishments. Dwelling on prowess in these areas alone diminishes the proper magnitude of the Japanese achievement, it ends up being a form of distortion. Further, the assumption that fine engineering and a high GNP can exist in isolation is a very dubious one, at best.

The argument matters. If the conventional view is indeed wrong, it means that the Japanese pose a far greater challenge to the outside world than is widely understood. An imitative country that got lucky has little long-term significance; but a deeply creative civilization at the forefront of change has importance for everyone.

To establish Japanese creativity, we shall look in some detail at two indications pointing to the profound modernity of Japanese life: the transmutation of Western civilization within Japan itself into something quite distinct; and - even more important - the prominence of Japanese culture and artifacts outside Japan. Together, these patterns go far to establish the originality and modernity of Japan since the mid-nineteenth century.

JAPANESE CREATIVITY

Japanese made the very act of borrowing into an act of great creativity. Prototypes were learned, imitated exactly and with skill, then quickly developed in new and distinctive ways. In the end, the model turned into something new and invariably original. From the great to the humble, what started as Western rapidly took on a clear Japanese cast.

Hiden, the tradition of initiating students to a body of confidential knowledge, is still relied upon for the transmitting of knowledge. Its legacy causes Japanese students to undertake educational enterprises in a serious, long-term, Zen-like way ("a student walks seven feet behind his teacher, lest he step on his master's shadow"), and inspires dedication to learning in areas where the West hardly pays it attention. Take driver's education, which is almost ignored in the West but which requires intense efforts in Japan. During the first hour of the course, a student practices the precisely proper way to open a car door (lift the handle gently, pull the door exactly four inches, stop, look in both directions, and open the door the rest of the way). A student can be inducted into these mysteries either by devoting the good part of one day a week for up to six months. Or he can attend one of the country's 150 residential driving schools, where he devotes 17 to 20 days to nothing but intensive instruction on driving.

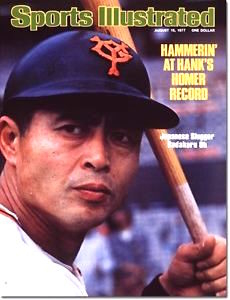

Sports Illustrated cover from August 15, 1977, featuring Sadaharu Oh. |

Oh also notes that team cooperation has an importance unknown to American players. "In my country it is impossible to play just for oneself. Everyone wants to play that way - but you cannot show it. You play for the team, the country, for others." Loyalty is reciprocated by management; former Yomiuri Giants often work for the Yomiuri newspaper, while Nippon Ham Fighters subsequently end up selling ham. Appropriately too, Robert Whiting subtitles his study on baseball in Japan, "baseball Samurai style."

Exchanging business cards developed from a Western custom but quickly took on a distinct Japanese flavor. Cards are carried more widely (even by high-school students), used in more situations (bar girls give cute cards to their patrons), exchanged more often (one guess has 12 million of them handed out each day), made more elaborately (they can be made of metal or carry photographs, smell aromatically, play music, or be downloaded into a computer), and then scrutinized with unique care.

The Japanese exchange of business cards involves a distinct protocol. |

Department stores began by emulating those in the United States but quickly took on distinctive Japanese elements of culture and entertainment. For example, the stores sponsored major art galleries and for many years had game rooms and hired bands. Vending machines in Japan purvey goods - such as beer and hard liquor - that are nowhere else sold by machine.

Cuteness (kawaii) has been taken to novel extremes; the elements - pink colors, bunnies, strawberries, and Snoopy dolls - come from the West but the context of their use, their composition, and their widespread adoption is original. For example, the typical cake at a Japanese wedding, standing 15 feet high and frequently covered with blinking lights and dry ice steam, towers over the bride and groom; but the whole structure, with the exception of one portion cut by the newlyweds, is made of rubber.

The comic strip arrived from the United States in 1923 and quickly transcended its American origins to become a staple of Japanese entertainment and a major force in popular culture. Today, it constitutes over one-quarter of all printed matter in Japan, a statistic that appears less surprising when one sees the telephone-directory-sized volumes produced each week and sold in huge numbers to children and adults. Shonen Jump sells over 2.5 million issues a week and the largest circulation comic of them all, Champion, sells over 4 million. Even elite universities sponsor comic clubs where students publish their own magazines.

With regard to food, the Japanese package a lunch of sandwich, potato salad, and lemon pie in the Japanese bento style, in a lacquer box subdivided into parts and garnished with green. The Japanese cuisine pays little attention to food being hot or cold; neither does it serve meals in a strict order; as a result, even French food is served in Japan with a certain nonchalance.

Shoes became popular in the 1870s, before any other Western-style clothing, and right from the beginning, the Japanese adapted the form to their own taste. "In early Meiji there was a vogue for squeaky shoes. To produce a happy effect, strips of 'singing leather' could be purchased and inserted into the shoes."

The Japanese made the Christian holidays of Christmas and New Year's their own, and in the process transformed them. For background, two facts must be remembered: less than 1 percent of the Japanese populace is Christian and the Japanese traditionally celebrated Lunar New Year (with the rest of the Chinese cultural world) in late February. Now all has changed. The holiday season begins with "Forget-the-Year" revelries and continues for nearly two weeks. During that time businesses shut down and alcoholic consumption soars. The symbols of Christmas, taken primarily from the United States, are everywhere. But they are not serious. "This Shinto-Buddhist land has imported piped jingle bells, sparkling trees and yo-ho-hos in the same spirit as it has adopted Mickey Mouse: as pure fun."

New Year's is an even more extravagant occasion. Since 1873 it has taken place on 1 January (not late February) and it, not Christmas, is the main time for exchanging gifts and cards. The Japanese have the exchange of cards down to a science; in contrast to the rest of the world, where holiday cards dribble in over a period of weeks, the Japanese post office assures delivery on 1 January, so long as a card is mailed by 28 December. A typical household receives hundreds of cards on that date. Indeed, how many cards one receives and from whom has not just social implications but can affect one's credit rating.

A consumer-finance company, Honobono Reiku, says that it gives loans more readily to those who get many nengajo [New Year's cards], on the theory that these must be people of substance. After all, said a company official, Katsuhiko Hasegawa, "When your business goes bankrupt, you get fewer cards."Honobono Reiku even evaluates the type of card. Those who get handwritten greetings are deemed worthier than those who received the pre-printed varieties. Senders are judged, too, on a point system of 1 to 5. A card mailed by a former teacher or an expensive restaurant gets a 5, but one from a politician is worth only a 1 because office-seekers hand out nengajo as readily as promises.

The Japanese have developed a custom of celebrating the Christmas and New Year's season by listening to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. Gigantic choruses (numbering up to 10,000 participants) rehearse for months in advance and the country's leading orchestras play the symphony over and over again during December. This represents an original Japanese custom, not a Western one, that evolved out of two Western imports, the holidays and the music.

Along similar lines, the Japanese adopted Valentine's Day and doubled it. On the original date of 14 February, women give presents to men; on 14 March, dubbed White Day, men reciprocate with presents to women.

The use of English is startlingly original. Japanese company names, advertising, and decorative uses of the English language are to a native speaker often strange and sometimes incomprehensible. A shirt proclaims "Groovy Question" and a jacket states "Nice Box 317-Lover Come Back to the Mysterious Club." A bag is inscribed with "West Coast Sportsgoods Spirit," a loose-leaf folder has "American Way Pulse of Stationery." The thoughts on a sweatshirt range from the absolutely obscure ("Boom Strap-Articles of Knitting Grew") to the racy ("Mr. Zogs Original Sex Wax-Never Spoils, the Best for Your Stick").

Brand-name goods also carry odd tags. Pocari Sweat is a popular drink, Creap a coffee lightener, and Potato the name of a rock magazine. Despite its name, Goo Soup is said to be of delicate taste. Tags on watches sold by the YOU company include the inscription "Sentimental Graffiti Orient." A liquor slogan exhorts: "Be more Scotch and have more wine." Even foreign corporations get into the spirit. On vending machines, Coca-Cola products carry the slogan "I feel Coke," while cans proclaim "I feel Coke & Sound Special."

Despite its name, Pocari Sweat has a mild grapefruit-like taste. |

This inventive use of English - using words purely for effect, disregarding meaning - represents not errors but a wholly distinctive way of using this foreign language. Unlike other non-English speaking peoples, who use English only to communicate with foreigners, the Japanese use it for their own internal purposes, and are surprised that foreigners even take notice of it. English takes on an iconographic purpose, becomes something to be seen, not read, much less taken literally. The Japanese have chosen to play with the language in their own way; and who is to stop them? Some now call this Japlish or Janglish; less delicately, Basil Hall Chamberlain a century ago called it "English as she is Japped."

In politics, parliamentary democracy received a new twist with the system of a strong bureaucracy and weak politicians, of party factions (habatsu), and of strong central and weak local governments. The Japanese police portrayed themselves right from the start very differently from the Western models. A 1874 regulation for Tokyo officers explicitly mixed power and benevolence in a distinctly Confucian manner: "The officer is parent and older brother, the subordinate is child and younger brother." In line with this self-conception, police intruded in matters of no concern to their Western counterparts. Not only would they haul men wearing the (old-fashioned) topknot off to the barber and make sure pedestrians walked on the left, but they inspected houses in the fall and spring to insure that the bi-annual house cleaning was properly carried out.

In these and other ways, the Japanese adopt Western cultural forms and mold them to their own taste and purposes, adding twists that Westerners would never imagine. What was once alien has been incorporated, made indigenous, and evolved in new and distinctly Japanese directions. No other people has taken Western ways in to such a degree that can play with them and make them over into indigenous artifacts. Unlike the rest of the non-Western world, where modernity is almost entirely derivative, in Japan it is original.

JAPANESE INFLUENCE ON THE OUTSIDE WORLD

Influence on the outside world, and the West in particular, provides an even more important indicator of creativity. Both Old and New Japan had rich and many-sided influences on the outside world. A full accounting of their impact would require an entire book; what follows are a few notable examples.

Civil Institutions

Business. Many of the characteristic features of Japanese management had already emerged in the 1890s, including "the emphasis on generalists rather than specialists; a reliance on formal intra-organizational training to provide needed skills and inculcate loyalty toward the organization and a strong personal sense of duty; the standardized, rational structure of bureaus and sections."

From this, the Japanese created a unique business structure, what Murray Sayle has dubbed a system of tribal bureaucratic capitalism. It includes the formation of distinctive forms of corporations, such as commercial combines (the zaibatsu) and trading companies (sogo shosha). Japanese innovated in the area of cooperation between corporations and government agencies (such as the Ministry for International Trade and Industry, MITI). Japanese corporations are uniquely involved in their employees' lives, sponsoring everything from calisthenics to marriage bureaus ("It is the duty of the company to help with this").

Within the factory, the Japanese took the American concept of quality control circles and refined it to the point that factory inspection was rendered almost unnecessary. This in turn made possible the just-in-time (kanban) method of industrial production, with attendant savings in production costs. Innovations in management included ringisei (circular discussion system) and nemawashi (informal discussion and consultation). Japanese firms pioneered the practice of developing close relations between management and workers, and assuring lifetime employment in return for in-house labor unions becoming docile. Operating on the principle that "workers, not managers, build cars," workers received ever-more responsibility, while the ranks of managers were thinned out.

The great industrial and commercial success Japan enjoyed in the 1970s made its business practices the subject of many studies seeking to evince their secret and make it available to the outside world. While the direct application of Japanese methods had only limited success (for example, Sears World Trade, created on the model of a sogo shosha, quickly floundered), the example of Japanese firms, their efficiency, and their spirit profoundly reshaped the international face of business. Rivals who had never worked together before came to feel the need to combine resources to fend off the Japanese challenge; thus, the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation was founded by a consortium of major American firms to compete more effectively against the Japanese.

Many of the key characteristics of the Japanese corporation are not tied to Japanese culture, and so can be successfully exported. Such features include: variable compensation to employees, enterprise labor unions, greater job security, the kanban system of manufacturing, more willingness to search for innovative technology, the elimination of dividends to stockholders, closer relations with banks, and a greater emphasis on market position than profits. D. Eleanor Westney, a specialist on Japanese organizations, has predicted: "it seems likely that the growing internationalization of Japanese commerce and industry will eventually make Japan an important exporter of organizational patterns as well as of cars and consumer electronics."

Government. Already in the Meiji period, after a short period of unimaginative imitation, the Japanese went on to evolve the administrative institutions they had copied. In some cases, they came up with innovations in advance of the West. Two institutions, the police and the postal system, clearly show this pattern.

In the case of the police, the Japanese quickly introduced two important features, one having to do with recruitment and the other with deployment. Quite in contrast to the Western models they had studied, the Japanese police leaders hired administrators from among graduates of the country's leading universities. Already in 1893, long before Western police organizations attracted university graduates, graduates of the Imperial University began to join the Tokyo police force. Formal police education began with the national Police Officers Academy, the first such institution in the world, founded in 1885. The training provided by the National Police Academy outmatched anything found in the West before the 1920s, and it showed; Japanese officers had early on achieved a level of discipline and honesty not found in the West until much later. University graduates and specialized education soon led to professionalization, a step which had been sought by European and North American police administrators. Professionalization became so integral to the police that, five years after government funding for the Academy ended in 1904, the police association itself paid for a new Academy - a perhaps unique event in the history of bureaucracy.

Second, Japanese police officers were deployed according to novel principles. In an effort to consolidate the beat system, widely used in Europe, they developed small stations for urban and rural needs. In cities, the police worked out of three-man police boxes (koban); in rural areas, they were based in one-man residential posts. These small stations gave the police a consistency of dispersion and penetration unmatched in Europe. It took almost exactly a century for koban to reach the West, finally making it in 1987, when the first ones were established in San Francisco. As in Japan, the police box is seen as a more efficient and less expensive version of the classic police foot patrols.

A typical koban, or small police station, this one in Akasaka in Tokyo. |

A postal system emerged along similar lines. The Japanese borrowed mostly from the British system, the most advanced in the world, and immediately began experimenting. They used new forms of transport (including rickshaws), relied on private companies to deliver much of the mail, advertised for business, offered various services gratis, and established novel organizational forms. The results were impressive. By 1912 a retired British postal official deemed the Japanese system "splendidly organized." By 1976 (almost a century after the Japanese had first imitated the British system), the British government dispatched a committee to study the Japanese postal service, seeking to learn from its organization and its use of technology. The post office provides a fine example of the density of the relationship between Japan and the West; the Japanese copied the British prototype and then taught their teacher something back.

In addition to these innovations, the Japanese government experimented with other important practices. In the field of energy, for example, its sale of coal mines in 1869 was not just "the most extensive non-coerced privatization in economic history," but also one of the earliest; and the decision to leave electrical supply entirely in private hands made Japan nearly unique among industrialized states.

It is no longer surprising that the West should look to Japan in the 1970s and 1980s, for this happens all the time. But two points are worth noting. First, the teacher was learning from the pupil within less than a century. Second, although the West could have profited from the Japanese experience already in the late nineteenth century, hardly anyone thought of doing so then. Instead, Japanese and Westerners alike saw Japanese innovations then as mere compensation for the backward conditions prevailing in Japan.

Education. Studies show that Japanese high school graduates have had the equivalent of four more years of school than Americans. The enormous emphasis on high school performance, culminating with the college entrance examination is then followed by relative relaxation during the university years.

Foreigners have long admired the impressive results of the Japanese school system. Henry Dyer, the British engineer, recognized the implications of this achievement in 1904:

Great Britain should not be above learning a few lessons from Japan.... Other countries, notably France, Germany, and the United States, and above all Japan, have developed their educational arrangements and applied the results to national affairs in such a way as to affect profoundly economic and social conditions at home and trade abroad.

Indeed, Dyer re-organized the Glasgow and West Scotland Technical College along the lines of the Imperial College of Engineering in Japan, making that college possibly the first Western institution to be influenced by the New Japan. Along similar lines, U.S. Secretary of Education William J. Bennett wrote in 1987 that Americans "should look for principles, emphases and relationships in Japanese education that are compatible with American values, indeed that tend to embody American values... to see how we might borrow and adapt them for ourselves."

Japanese educational methods have had other influences too. For example, the Suzuki Method of violin training, which applies traditional Japanese techniques of rote learning in new ways, found a substantial international following.

Scholarship

Science. Scientific training got off to a quick start in Meiji Japan as eminent European or American specialists usually spent a few years in Japan to train Japanese students (this was the case for physics, chemistry, zoology, botany, geology). In other cases (such as mathematics), the Japanese traveled to them. The vitality of this exchange quickly became apparent.

Shibasaburo Kitazato discovered the antitoxin against tetanus in 1890. The 1892 Diet bill creating an earthquake investigation committee made seismology a specialty of Japanese science, which quickly became a world leader in this field. Hantaro Nagaoka, who had the distinction of being the only non-Westerner present at the founding of the International Congress of Physics in Paris in 1900, soon after proposed the Saturnian model of the atom's structure (that is, a massive nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons), antedating by a decade the work of Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr. Kikunae Ikeda identified monosodium glutamate in 1908. Umetaro Suzuki discovered the first of the vitamins, B-1, in 1910. Kotaro Honda invented K. S. Magnetic Steel in 1916. Kyusaku Ogino showed the connection between ovulation and menstruation in 1923. Hideki Yukawa hypothesized the existence of the meson in atomic nuclei in 1934. Shin-ichiro Tomonago had a key role during the 1940s in formulating the theory of quantum electrodynamics. Japanese have received five Nobel Prizes in science; the only other non-Western scientists to have won prizes are one Indian and one Pakistani.

Despite these impressive results, the feeling has long existed in Japan and the West that the Japanese have not done their share of basic research, ignoring it in favor of research aimed at finding commercial applications. Even a Japanese prime minister, Yasahiro Nakasone, publicly stated that Japan is indebted to the West and "we now need to repay the favor." Spurred on in good part by foreigners (shades of the unequal treaties in the 1880s!), Japanese firms began to establish capabilities in basic research.

They acted with alacrity; according to one estimate, more than thirty major corporations established laboratories for basic research in 1982-87. Funds devoted to research increased by an average of 10 percent annually through the 1980s. Looking at 1985 figures, Americans spent $109 billion on research and development, the Japanese $34 billion, the Soviets $3 billion, West Germany $2 billion, and France and Great Britain each about $1 billion. (Changed exchange rates would double the size of the Japanese investment within three years.) By 1985, the Japanese spent a larger percentage than Americans of their gross national product on research and development (2.8 percent versus 2.7 percent); because a substantial portion of American funds went for military-related research, Japan out-spent the United States in civilian-related research.

Again, the results were impressive. Japanese took out more than half the patents in chemistry and produced most of the amino acids required for bio-technology. A massive particle accelerator costing $700 million, Tristan, placed Japan in the forefront of elementary particle research. A December 1988 report of the National Science Foundation in Washington concluded that the Japanese scientific endeavor had achieved "relative parity" with the American.

American universities and businesses responded to this effort with alacrity. Some 400 scientists began to study Japanese and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology offered courses in the language. Indices and summaries of Japanese articles were started up, most notably the monthly magazine of the Japanese Technical Information Service, providing 5,000 abstracts in each issue. Among Federal government institutions, a Congressional subcommittee published a report on the need to stay abreast of Japanese science and the Commerce Department proposed a joint venture with industry to program computers to translate Japanese into English.

Technology. Already in about 1869, the rickshaw (more properly, jinrikisha) was invented in Tokyo. It provided such an efficient and low-cost way to transport goods and people, the vehicle soon became a major export to China, the Malay peninsula, and India.

The Japanese take ideas or inventions from the West and make better use of them. As a result, they are the single most dynamic force in the application of technological advances. A few of the most important examples must suffice, for the list is very long: nylon fueled the synthetic textile industry, transistors and semiconductors spawned the electronics industry, and robotics, which were invented in the United States, have been most heavily applied in Japan.

Although long dependent on others' technology, the Japanese now generate much on their own. According to a 1988 report issued by the (Japanese) Science and Technology Agency, the 490,000 engineers working in Japan outnumber the combined totals of Great Britain, France, West Germany, and Italy. Whereas Japanese inventors had received only 4 percent of U.S. patents in 1970, they won 19 percent of them in 1986. By 1985, Japan received, after the United States, the largest flow of income from technological advances used by foreigners.

Examples of these inventions include: Junichi Nishizawa's many basic electronic devices, such as optical fibers and the PIN diode, a forerunner of the semiconductor. In June 1985, a missile tracking guidance system developed by Toshiba became the first Japanese military technology to be used by the U.S. government. According to a study that traced citations to prior inventions (as a way of tracing influence), starting already in 1976, scientific innovation in Japan outpaced that in the United States. The report held that Japanese patents were "at the leading edge of modern developments in technology." In appreciation, the American Electronics Association opened an office in Tokyo in 1984. The impression of Japanese imitativeness remains, however, and in good part because of this, foreign firms have adopted little Japanese technology.

In some ways, the Japanese achievement outside the hard sciences stands out even more, for while peoples of all non-Western countries have labored at the sciences, very few have made much effort at the liberal arts. Put differently, Turks have done virtually no original research on Japan, Japanese have done considerable work on Turkey, as well as on many other a range of historical, political, and anthropological subjects.

The Arts

Literature. Japanese influence was extensive, touching virtually every important nineteenth-century French writer. Almost to an individual, they showed interest in Japan or China and appreciated the arts of East Asia. More broadly yet, according to Kenneth Rexroth, "the forms of Japanese poetry, of the No drama, and even of the Japanese language itself, happen to parallel the development of poetry in the West from Baudelaire to Rimbaud, to Mallarmé, to Apollinaire, to the Surrealists."

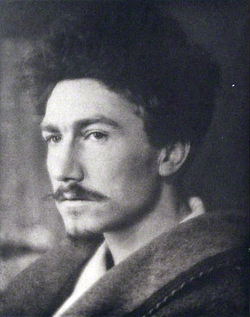

Japanese culture deeply influenced the poet Ezra Pound. |

English-speaking writers following these two, and influenced by their looking to Japan for inspiration, included Conrad Aiken, Richard Aldington, T. S. Eliot, John Gould Fletcher, Robert Frost, Amy Lowell, Archibald MacLeish, I. A. Richards, Wallace Stevens, and William Carlos Williams. American poets of the beat generation - Cid Corman, Robert Creeley, George Oppen, Carl Rakosi, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Louis Zukofsky - very clearly showed the impress of Japanese verse. Paul Goodman wrote five plays modeled on the noh form of drama. Kenneth Rexroth, an American poet, holds that "classic Japanese and Chinese poetry are today [1973] as influential on American poetry as English or French of any period, and close to determinative for those born since 1940." Looking at the whole picture, Earl Miner concludes that "over the long period of four centuries Japan and its culture have become increasingly important to our writers and have assumed the role, to use the phrase of Ezra Pound, of 'a live tradition' which has modified, refreshed, and helped shape much of the finest modern English and American literature."

Other Japanese forms also affected Western poetry. The haiku verse form (of seventeen-syllable poems) provided the central inspiration for the imagist school in France and England, and through it affected much of modern European poetry, especially that written by such Frenchmen as José-Maria de Heredia and Paul Louis Couchoud. Woodblock prints inspired Oscar Wilde to adapt coloristic images to his verse "studies" and "impressions."

Theater. Noh theater so impressed Portuguese Jesuits in Japan that from 1588 they wrote plays in the noh style to propagate Christianity - probably the first-ever Japanese cultural influence on the West.

Burdened with by a strong (and nearly sterile) tradition of realism, the European theater of the nineteenth century turned to the several Japanese forms to borrow elements of abstraction, stylization, and self-consciousness. Noh, with its bare stage, abstract symbolism, and austere music had perhaps the most profound impact on Western theater. Under its impact, highly elaborate scenes gave way to simple and nominal gestures. The revolving stage, patterned after kabuki theater, was introduced in Germany in 1896. Kabuki affected Bertold Brecht and continues to exert an influence on Western writers.

The shimpa (or shimpageki, "new school") theater which came into being under the impact of the West broke down the many restrictions of noh and kabuki. To great acclaim, a shimpa theater troupe already in 1899 toured Europe and the United States. Georg Fuchs, who founded the Munich Art Theater in 1908, derived his principles of rhythmic motion and of "the psychological course of the play" from shimpa.

Eventually, Japanese directors brought their methods directly to Western audiences. Thus, the avant-garde director, Tadashi Suzuki staged The Tale of Lear, his adaptation of Shakespeare's King Lear in several American playhouses during a 1988 tour. Relying entirely on American actors, Suzuki gave the whole production a Japanese quality. Characters on the stage hardly moved; instead, they relied heavily on expressive gestures and voices. Men played female roles. According to one reviewer, Joe Brown of The Washington Post, the result was a powerful new interpretation:

Their glittering, piercing glares reveal more about character than dozens of "natural" gestures and mannerisms, and their hybrid of English words and Japanese vocalization techniques results in a Shakespeare the likes of which you've never heard, filled with harsh, guttural barks, rapidly whispered outbursts and slowly broken sentences.

Cinema. Sergei M. Eisenstein, the influential Russian director and film theorist, held kabuki in the highest regard and argued that the sound film "can and must learn its fundamentals from the Japanese." Indeed, Eisenstein almost single handedly brought Japanese theatrical methods to bear on films, with wide and lasting effect.

Kabuki enjoyed a second wave of influence in the 1950s, through Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon. Kurosawa, like many Japanese directors, relied on kabuki's stylized forms of acting, stagery, and display, then blended these with psychological complexity and intellectual seriousness to achieve an ambiguous and exotic spectacle. Rashomon and other Japanese historical costume pictures (many of them about samurai) strongly affected European and American art films. Even Hollywood paid direct tribute to Kurosawa's films by imitating them: The Seven Samurai inspired the 1960 Hollywood remake, The Magnificent Seven; The Hidden Fortress inspired Star Wars; and Yojimbo inspired the anti-heroic style of "spaghetti Westerns" from Italy and Hollywood.

Akira Kurosawa's work heavily influenced Hollywood's film, "The Magnificent Seven." |

If Kurosawa was the best known Japanese filmmaker, others too had international influence. Nagisa Oshima, a member of the New Wave of the 1960s, mixed wry irony with powerful sexuality and radical politics; his best known films include Boy and In the Realm of the Senses. The films of Kenji Mizoguchi were known for the richness of their sheer beauty and the detail of their physical and psychological portraits. His main theme was the social condition of women; major films include Ugetsu, The Life of Oharu, and Sansho the Bailiff. Yasujiro Ozu crafted quiet, slow-moving stories about family drama. His movies inspired Jim Jarmusch's Stranger than Paradise and Down by Law. On a very different level, Ishiro Honda's science-fiction films, including Godzilla, gained a cult following in the West.

Music. Though the pace of composing activity in Japan is considerable, composers are little known outside Japan. The single exception may be Toru Takemitsu, who made a speciality of exploring (in both European and Japanese media) timbre, texture, and everyday sounds. Akira Miyoshi composed classic Western music. Toshi Ichiyanagi, Jo Kondo, Teruyaki Noda, and Yuji Takahashi wrote in an avant garde manner. Shinichiro Ikebe, Minoru Miki, Makato Moroi, and Katsutoshi Nagasawa wrote for traditional Japanese instruments. Maribist Keiko Abe was the best known of classical Japanese musicians and Toshiko Akiyoshi the most renowned of jazz players.

The Suzuki method has already been noted. John Cage is probably the Western composer most directly influenced by traditional Japanese music. Woodblocks have become standard in the percussion of jazz music. Yamaha, which sells 200,000 pianos a year, is the world's largest maker of musical instruments. At another level, the characteristic Japanese-style bar (complete with hostesses, a mama-san, and karaoke microphone) has begun to appear in Manhattan.

The Tokyo String Quartet and the NHK Orchestra are internationally the best known of Japanese performers of European classical music. Most renowned of the Japanese conducters is Seiji Ozawa, music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Performers with wide reputations include pianists Aki and Yugi Takahasi and percussionist Stomu Yamashita. With seven professional orchestras and three operas, Tokyo probably has the highest density of European classical music talent in the world.

Ultimately, nothing symbolizes the Japanese accomplishment quite so precisely as their absorption and adeptness at Western classical music. Bernard Lewis notes: "Though some talented composers and performers from Muslim countries, especially from Turkey, have been very successful in the Western world, the response to their kind of music at home is still relatively slight. Music, like science, is part of the inner citadel of Western culture, one of the final secrets to which the newcomer must penetrate." The Japanese alone have entered that citadel. Although there is nothing inherently modern about the classical music of Europe, and certainly nothing functional about it, the Japanese mastery of this artistic form confirms the whole of their recent career.

Dance. Young choreographers in the West have begun to look to Kabuki and noh for ideas in movement and staging. Butoh, the avant-garde form of dance that emerged around 1970, offered audiences a stark presentation of distorted expressions, silent screams, nudity, and primordial movement.

Painting. The story of the arrival of the first ukiyo-e (color woodblock prints) to Paris in 1856 is shrouded by legend; suffice it to say that their discovery by the painter Félix Bracquemond led to japonisme, a vogue for Japanese art that lasted from 1865 to 1895. Vincent van Gogh, for example, owned two hundred Japanese prints for studying purposes, briefly dealt in them commercially, and would have visited Japan had his money held out. A store devoted to Japanese art first opened in Paris in 1875; that same year, the East India House (precursor of the present Liberty's) opened in London and specialized in Japanese artifacts.

Japonisme might have had a limited effect except that it attracted the serious attention of superior artists and critics, including Théophile and Judith Gautier, Edmonde and Jules de Goncourt, José-Maria de Heredia, and Henri de Regnier. Through them, ukiyo-e permanently altered European conventions of color, perspective, empty space, symmetry, form, composition, and subject matter. In particular, these artists came to understand the appeal of irregularity and to appreciate the Japanese sensibility for the evanescence of nature. Japanese influence had a major role in inspiring the Impressionist movement in France, which caused perhaps the most profound change in the aesthetic of modern Europe.

Outstanding artists directly affected by the wood blocks included Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Théodore Duret, Paul Gaugin, van Gogh, Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edvard Munch, Pierre Renoir, and, above all, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Toulouse-Lautrec derived his subject matter directly from Japanese models; his posters of the Parisian demi-monde, for example, resembled Kitagawa Utamaro's courtesans of Tokyo's pleasure quarters. Further, he imitated the Japanese in the heavy use of shadowless pure colors and other elements of design and in his print-making technique. James Abbott McNeill Whistler had an important role in popularizing Japanese styles in the United States. Impressionists did not shy from crediting Japan. Duret called the Japanese "the first and finest impressionists," while van Gogh dubbed Japanese art "true religion."

Subsequently, the extreme abstraction of Vasili Kandinski's work clearly showed the inspiration of traditional Japanese aesthetics. Recent painters such as Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Rauschenberg also showed the clear impress of Japanese art. Japanese calligraphy and the "modulated line" had great impact on such Western artists as Hans Hartung and Pierre Soulages, both of whom gave a central place to ideograph-style elements.

Japanese artists have had some success and influence in Western-style painting. The leading figure here was Tsuguji Fujita (1886-1968), who gained a considerable reputation in France. He assimilated so thoroughly to French ways that he was late in life baptized a Catholic; he died shortly after decorating the Chapel of Our Lady of Peace in Reims. If not entirely successful in their accomplishments, Japanese artists were unique in their unremitting effort to assimilate the techniques of Western painting.

Design. At its most profound level, the Japanese example encouraged Westerners to apply aesthetic considerations to the small things in life. The sensibility of the tea ceremony and by the wrapping of a package in a store represents an integration of design and an attention to detail traditionally unfamiliar in the West. Japanese handicrafts offered Westerners a simplicity and aesthetic they found lacking in their own civilization. This approach came to fruition in the work of Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus; it has since become widely imitated and almost universally accepted.

On a more specific level, Japanese stylists had major influence in the West at two different times. First, the Arts and Crafts Movement in England, which celebrated individual work and authentic materials, drew in a general way on Japanese artisanship and style. The movement, which flourished in the 1880s and 1890s, then spread to Europe and North America. At the start of the twentieth century, Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) incorporated significant stylistic elements deriving from Japanese paintings and ornaments. For example, Art Nouveau abandoned the long European heritage of using only gems and precious metals in fine jewelry, and took up some of the materials associated with Japanese crafts; it also incorporated nature themes that owed much to Japanese art.

Latterly, the "Japanese design revolution," a movement with many practitioners but little in common, had wide international influence, especially in architecture, fashion, and graphics. The stylists shared an emphasis on making the most of materials, be it wood or plastic, silk or concrete; and on emphasizing extreme cleanness of design and great attention to detail.

Architecture. The restrained, monochromatic aesthetic known as shibui deeply influenced twentieth-century architecture and interior design. Elements deriving from Japan included: simplicity of form, exposed materials, wide use of wood, the post and lintel construction (closely tying interior spaces to exterior appearance), the fluid use of inside and outside spaces, rooms with multiple uses (such as one-room combinations of living-rooms and dining-rooms), floor-to-ceiling windows, varied textures and fabrics, and light furnishings. Japanese ideas had a particularly strong impact on domestic architecture in the United States starting in about 1905 and culminating in the post-World War II period. In particular, Frank Lloyd Wright transmitted many Japanese effects to American architects.

If the early Japanese influence on Western building was stylistic, a second, more directly architectural influence began in the 1970s. Actually Japan had had no architects, only master carpenters, until the Meiji period; and, until the mid-1960s, architects usually worked for construction companies - not ones eager to encourage creativity. After about a century of copying from the West, the Japanese builders found their own style, and it turned out quite differently from what the student of shibui might have expected.

The main stadium built for the 1964 summer Olympics in Tokyo. |

Indeed, by taking Western concepts to their logical conclusion, Japanese architects introduced new elements. Reyner Banham explains that "it is the marginal minor differences in the thinkable and the customary that ultimately make Japanese architecture a provokingly alien enclave within the body of the world's architecture." Peter Popham characterizes the Japanese touch:

Heaviness, thickness, great tortoiselike longevity, massive size: these have been the prerequisites of architectural respectability in the West from Stonehenge to Michael Graves. Ever since the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan's architects have been dutifully grafting these stony Western blooms onto the native stem, but skepticism and anarchy, frivolity and pettiness have always been erupting in the grass roots. Architecture can be fun! And it needn't last forever! Come and see!

The Japanese participated actively in the definition of Post-Modernism. Reyner Banham argues that it could not be otherwise. Who but the Japanese could so playfully adopt bits of the Western orchestral tradition to create a wholly new style? "Insofar as Post-Modernism involved the breach of modernism's ingrained and unthinking taboos on historical references, it could hardly be under any influence but Japanese."

Fashion. Already in 1858, the mills of Manchester produced cotton prints based on Japanese woodblock patterns.

What is sometimes called the "New Japan Style" became a major new force in fashion in 1981. The style relied on experimentation with materials, wrapped and draped forms, stark black-and-white designs, and large masses of cloth. It represented a move toward unconventional designs, an absence of color, and novel shapes loosely based on traditional Japanese clothing. Hanae Mori was best known for her evening wear, Issey Miyake for his oversized adaptations of traditional Japanese worker's clothes. Yohji Yamamoto elaborated on Western clothing with bold lines, striking colors, and loose, flowing garments; the whimsical results produced a distinctive hybrid effect.

Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons was the most unconventional of the major designers, the one most dedicated to experimenting at the outer limits of the possible in clothing design. Kawakubo turned clothing inside it, exposing seams; added holes for third arms and second necks; used only four monochromatic colors (black, navy, charcoal, and white); avoided decoration; and molded the clothes to the body in a highly characteristic manner. Her sparse stores emulated modern art museums. As one admirer, Leonard Koren, noted, "if self-enlightenment were possible in the context of a clothes boutique, surely it would happen in this one."

Comme des Garçon's 2011 line takes clothing to its limits. |

Several Japanese couturiers opened branches in Paris; others bought up such French designer labels as Courrèges. That Jürgen Lehl, a designer specializing in textiles, lived in Tokyo further attested to the international quality of Japanese fashion.

In the Meiji period, Japanese and Western clothing - wafuku and yofuku - had been utterly distinct. Women wore either kimonos or dresses. Men wore kimonos, or they wore suits, ties, hats, and shoes. But then two things happened: Western clothing evolved in new ways, and Japanese designers actively participated in that evolution. As a result, the old lines, once so clear, became blurred beyond recognition. Fashion offers an example of an area in which the tension between Japanese and Western ways has been nearly resolved, leading to a new synthesis.

Other

Philosophy and religion. The most profound Western interest in Japan was philosophical in nature. Rationalist Europeans of the eighteenth century, looking outside Europe for confirmation of their belief that civilization did not require religious foundations, found in China and Japan what they were looking for. More broadly, Confucian states for three centuries have offered an attractive alternative to Westerners discontent with their own society. Geographic remoteness and cultural dissimilarity also enhanced the utility of the Confucian countries as proof in many arguments. The specific East Asian virtue has changed many times - secularism, aesthetics, lotus-land, purity of revolutionary spirit, or management style - but the underlying quest remained the same.

Zen Buddhism enjoyed several vogues in the West, particularly as interpreted by Daisetu T. Suzuki and Alan Watts. What was dubbed "Zen for Westerners" had a major influence on American college students and existentialist thinkers. Zen crystallized an interest in alternatives to Western religion in the 1960s, especially in the United States.

Food. In addition to the standard fare of Japanese cuisine - sushi, sashimi, miso, soy sauce, teriyaki, tofu - much of which found a favorable reception in the West, the mix of styles has had a broad influence. The lightness and delicacy of nouvelle cuisine, along with its emphasis on fresh ingredients and spare, stylized presentation, showed an unmistakably Japanese touch. Faddish restaurants in the United States prepared pizza with wasabi (a horseradish normally eaten with sushi), health food stores sell seaweed, and dried noodle soups (ramen) could be found on market shelves in many countries. Tofu found a niche, and even became the basis of an ice cream-like desert. Coriander and Shiitake mushrooms found followers among the gastronomically ambitious. It is probably only a matter of time before bento boxes (portable lunches packed in small wooden cases) turn up outside Japan, and other new influences will quickly follow.

Dry beer has succeeded internationally. |

Athletics. Mutual influences between Japan and the West in athletics are unique. While many non-Western countries took up soccer, the Japanese learned a great number of sports, including baseball, golf, tennis, volleyball, and skiing. As with more serious pursuits, so too with sports; when the Japanese adopted an activity, they did so with determined thoroughness. Sometimes their skills shocked foreigners; in 1896, after years of Japanese importuning, Americans living in Yokohama agreed to a Japanese-American baseball game. Although expecting to overwhelm the Japanese high school students, the American businessmen and sailors lost by a score of 29-4. They then dropped the subsequent two games by equally lopsided scores (32-9, 22-6). Coming at a moment of acute self-doubt among Japanese, the effect on the victories was electric. As the students' president said, "This great victory is more than a victory for our school; it is a victory for the Japanese people."

But the Japanese have not just learned Western sports; equally noteworthy, they (and, to a lesser extent, the Chinese) alone spread their athletics to the West. Judo, jujitsu, karate, and other martial arts became widely practiced. FBI and Secret Service agents in the United States studied aikido, a technique for evading and disarming attackers. Judo became an Olympic sport in 1964, the only event of non-Western provenience at the games. (Interestingly, Soviet - not Japanese - athletes won the greatest number of medals in judo.) A relay running race called ekiden was invented in Japan in 1917 and first performed outside the country in 1988, when a major contest was staged in New York City.

A Japanese team first went to the Olympic games in 1912, before any other non-Western state except India and Egypt. Japan's athletes have won a total of 237 medals, far more than any other non-Western state. Turkey comes in distant second with 45, followed by China with 32 and Iran with 29. India has only 14.

Miscellaneous. Some Japanese products spread widely, including paper lanterns, bonsai (dwarf) plants (and more rarely, bonkai, or tray scenes, which replicate whole landscapes in miniature), hot tubs, kite-flying, the game of go, and futons. A few practices found devotees in the West, including communal bathing, origami, and the tea ceremony (cha no yu). The careful arrangement and appreciation of natural forms exemplified by flower arrangement (ikebana) and rock gardens offered an alternative to traditional Western perceptions of nature.

On a different note, Japanese popular culture has begun to spread abroad. The fad of getting lost and finding one's way out of large, wood-paneled mazes can be pursued in several countries. Transformers (the children's toy) and Nintendo video games became extremely popular; can Japanese-style comic books be far behind?

Loan words in English from Japanese stand out for their references to significant, even admirable cultural features. They include: banzai, bonsai, futon, geisha, go, haiku, hibachi, judo, jujitsu, hara-kiri, kabuki, kamikaze, kimono, mikado, noh, origami, ramen, rickshaw, sake, samurai, soy, sukiyaki, sumo, sushi, tatami, tempura, teriyaki, tofu, tsunami, tycoon, zen. Just as "China" came to mean porcelain, so "Japan" after 1688 referred to lacquerware, porcelain, and silk. One Japanese word has even become slang: "just a skosh" comes from the Japanese word sukoshi (a little).

The Japanese have even created words in English that have gained currency, such as the just-in-time factory system and OA (office automation).

The Future

Already by the 1920s, the Japanese had caught up with the West in some areas of endeavor, including scientific research and artistic experimentation, and were exerting an influence abroad. Today, the Japanese are ahead in a wide variety of institutional, scholarly, and artistic fields. Probably, this is just a foretaste of the influence yet to come. In good part, the size, affluence, and modernity of Japan propels Japanese culture outward; but so too does the Japanese' deep appreciation of things Western.

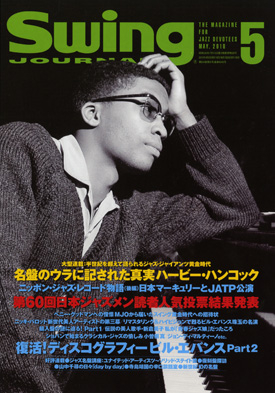

Jazz offers an excellent example to demonstrate the second point. The Japanese contribution to jazz has until now been modest, as composers and musicians did little more than imitate the styles of foreigners. But there exists an intense interest in jazz music in Japan that has two implications for the future. First, Japanese involvement is affecting music produced in the U.S. elsewhere. Jazz coffee shops (which play wide selections of music on state-of-the-art equipment) have proliferated, and Japan hosts three international jazz festivals a year. The Japanese Swing Journal sells 400,000 copies a month (compared to only 110.,000 copies of the best-known American publication, Downbeat) and roughly half of some American jazz albums are bought by Japanese. Indeed, according to one American producer, Michael Cuscuna of Blue Note Records, "Japan almost single handedly kept the jazz record business going during the late 1970s. Without the Japanese market, a lot of independent jazz labels probably would have folded, or at least stopped releasing new material." This is too big a market to lose, so American and other artists must increasingly pay attention to Japanese taste.

Jazz offers an excellent example to demonstrate the second point. The Japanese contribution to jazz has until now been modest, as composers and musicians did little more than imitate the styles of foreigners. But there exists an intense interest in jazz music in Japan that has two implications for the future. First, Japanese involvement is affecting music produced in the U.S. elsewhere. Jazz coffee shops (which play wide selections of music on state-of-the-art equipment) have proliferated, and Japan hosts three international jazz festivals a year. The Japanese Swing Journal sells 400,000 copies a month (compared to only 110.,000 copies of the best-known American publication, Downbeat) and roughly half of some American jazz albums are bought by Japanese. Indeed, according to one American producer, Michael Cuscuna of Blue Note Records, "Japan almost single handedly kept the jazz record business going during the late 1970s. Without the Japanese market, a lot of independent jazz labels probably would have folded, or at least stopped releasing new material." This is too big a market to lose, so American and other artists must increasingly pay attention to Japanese taste.

Second, the existence of a large and increasingly sophisticated home market offers fertile ground for Japanese musicians to experiment and then to lead. Attempts to combine jazz with traditional Japanese music have already begun; these blendings are likely to influence jazz as they have architecture and clothing. It seems safe to predict that the Japanese before long will become a major force in jazz, as in a wide variety of other activities.

Some observers feel that Japanese culture holds the key to the future. One contrast that keeps coming to mind is with France. A French architect living in Tokyo, Richard Bliath, observed that Tokyo "is the only city with an architecture of the here-and-now. The past does not exist, much less the future. Paris is still imbued with the spirit of 1789, whereas here there is constant construction and demolition." According to Jay Specter, a New York interior designer: "The future belongs to the Japanese. When I am in France, I am fascinated by the culture, by the decoration, the furniture, the art. But I can't help feel that a great deal of it belongs to yesterday. Japan, to me, looks like tomorrow." For him, "a simple approach to elegance, a beautifully edited point of view... in many ways looks like a view into the twenty-first century." Bernard Portelli, a French coiffeur who redid his Washington salon along Japanese lines agrees: "French style - it's over. There's nothing new, nothing in food, nothing in clothes. They're following the Japanese; that's all they can do." This sentiment is not new: decades ago, Frank Lloyd Wright is said to have told an aspiring architect he met on a ship going to Rome, "Sir, you're headed in the wrong direction."

In all areas of culture - not just business, science, and technology - the Japanese have an eclectic, unfettered approach which, combined with the prosperity of the country and the cosmopolitanism of the populace, permits explorations that others admire and imitate. As Herbert Passin put it, "Japanese no longer simply copy the modes of the outside world; they now participate actively in the development of international styles." Japanese scientists are fettered by a rigid system, but artists are free to follow their interests, unrestricted by conventions. Having mastered Western forms no less well than their own, the Japanese are now free to experiment. The tension between Japanese and Western models has already proven to be a fertile one; it also promises to be deeply influential.

Further Reading

Leonard Koren, New Fashion Japan (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1984).

Earl Miner, The Japanese Tradition in British and American Literature (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1958).

Kuniko Miyanaga, The Creative Edge: Emerging Individualism in Japan (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books, 1991).

Hiroyuki Suzuki, Reyner Banham, Katsuhiro Kobayashi, Contemporary Architecture of Japan 1958-1984 (New York: Rizzoli, 1985).

D. Eleanor Westney, Imitation and Innovation: The Transfer of Western Organizational Patterns to Meiji Japan (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press: 1987).

Daniel Pipes, director of the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia, recently published The Rushdie Affair (Birch Lane Press) and Greater Syria (Oxford University Press).

Sep. 1, 1998 update: Music comes up in passing in the above analysis; I look into it in much greater detail in "You Need Beethoven to Modernize" in the Middle East Quarterly.

Sep. 1, 1998 update: Music comes up in passing in the above analysis; I look into it in much greater detail in "You Need Beethoven to Modernize" in the Middle East Quarterly.

Oct. 1, 2014 update: China has similarly been accused of lacking creativity. Shaun Rein disproves this myth in The End of Copycat China: The Rise of Creativity, Innovation, and Individualism in Asia (Wiley).