What is going on in Central Asia and in Turkey has completely changed the region's geo-politics.

-- Akbar Torhan, Iran's minister of defense and armed forces logisticsThe very emergence of Central Asia onto the scene of world politics exerts a strong ripple effect on such states as Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, and others, potentially unleashing regional conflict, wars, separatist or irredentist movements, and religious extremism that affect the broader stability and security of the surrounding states.

-- Graham Fuller

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of six mostly Muslim republics from the former Soviet Union has prompted much concern about their falling under Middle Eastern influence. But Middle Eastern states have attained little power over those republics; ironically, the impact goes the other way. The independence of republics in the Transcaucasus (Azerbaijan) and Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan), has profound implications for the Middle East, and especially for their four immediate neighbors - Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Turkey's former prime minister Süleyman Demirel exaggerated only slightly when he called the independence of these states (called henceforth the ex-Soviet Muslim republics or the Southern Tier) "the event of our era." Indeed, the Southern Tier's resumption of history may well have enormous consequences for the Middle East.

Middle Eastern Impact on the Southern Tier

Reporting from Central Asia and Azerbaijan since late 1991 has concentrated on the competition for influence over them among Middle Eastern states. The rivals include primarily Turkey and Iran, as well as Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Ankara sees success at wooing the Southern Tier as a means of advancing Turkish secularism as a model, while Iran's success would win support for that country's anti-Western Islamic model.

To be sure, this competition does exist: Many Middle Eastern states saw an opportunity in about 1990 to gain influence in what seemed a virgin territory. Turks swooned at the prospect of leading a substantial bloc of Turkic speakers. Iranians jumped at the opportunity to reassert their historic cultural influence, now laced with Khomeinist Islam, over the Southern Tier. Pakistanis looked to Central Asia as a place to do business and establish a strategic hinterland versus India. Some Tajik and Uzbek Afghans looked to the region for allies. Saudi Arabians quickly geared up their Islamic apparatus to operate in a new region. Both Israelis and Syrians actively sought out friends in the Southern Tier. The ensuing competition had political, strategic, economic, ideological, and cultural dimensions. All these states dispatched diplomats to the Southern Tier; signed cultural, trade, or security protocols; beamed radio and television broadcasts; provided loans; and trained students.

But activity alone does not guarantee influence. Indeed, the Middle Eastern states have so far exerted little real authority in any area of Southern Tier life, from military affairs to religious practice. This generalization holds especially in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the Southern Tier's most populous and powerful states; it also applies to Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, where Turkey and Iran, respectively, enjoy greatest strength.

Why so little impact? Because Middle Eastern states are weak and divided, while the Southern Tier is proud and wary.

Middle Eastern weakness. Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan all suffer from severe limitations. Not one of them has the cultural, economic, or military means to carve out a sphere of influence. In addition, each state has its own special shortcomings. Although Iran's location will surely mean commercial and transportation links to the Southern Tier, the country's international isolation much reduces its attraction for states just emerging from three generations of colonialism and political quarantine. Also, its severe, unremitting Islamic order puts off peoples accustomed to secularism. Saudi Arabia competes, but its flimsy manpower base, remote location, and alien religious customs make it a less than formidable contender. As for Pakistan, it suffers from perpetual instability and wrenching poverty, and so can neither project power nor serve as a convincing model for others.

The Southern Tier. |

Of all the Middle Eastern actors, Turkey has the most active program for the Southern Tier and is widely seen as the most plausible influence over that region; its weaknesses therefore deserve more detailed consideration. Western notions to the contrary ("Turkey has the strongest historical and cultural links"), not only is Turkey geographically remote from Central Asia, but it enjoys few historical or cultural ties to that region. Istanbul never ruled Central Asia; conversely, Central Asia ruled Anatolia only momentarily (under Tamerlane) six centuries ago. Ottomans concentrated attention on their vast empire from Hungary to Yemen, not on distant Turkestan. Consequently, they had little cultural impact there until the decades just before World War I. The Soviets broke communications between the two areas, so that Kemal Atatürk's Westernizing reforms in Turkey during the 1920s and 1930s had almost no effect in the Southern Tier.

Turkish politicians sometimes portray their country as a middleman between the former Soviet republics and the West. Turks hope their Western orientation will strongly appeal to peoples emerging from three generations of totalitarianism. But how well can Turks serve this function if they themselves have not been let into the European Community ? And even if they can, why should the newly emerging states look to a peripheral member of the West rather than approach the key players directly?

Anecdotal evidence suggests Central Asian disappointment in Turkey. Students report poor conditions for study, businessmen find capital limited, and religious figures don't care for the country's secularism. All of them encounter a language more difficult to understand and a culture more remote than expected. And while the Turks have extended their media - television and newspapers especially - to the Southern Tier, they do not custom-design materials for these new audiences. Once the novelty of their media fare wore off, this severely restricted its appeal.

Turks lack the capital to carry through on their ambitious economic plans. Utbank, a joint Turkish-Uzbek commercial bank established in Tashkent to considerable fanfare, had a meager $2 million capitalization. In by far the biggest deal so far, the Turkish company BMB signed an $11.7 billion deal to operate four oil fields in Kazakhstan. But a few months later it was reduced to making a public appeal for an $800 million loan over four years ("and $200 million of it very urgently") because its own funds would not permit it to carry through the contracted prospecting in Kazakhstan. In general, Turkish entrepreneurs have become active in small-scale efforts (commerce, training, transportation), but have forfeited the larger undertakings (in oil, gas, gold) to Western and Asian corporations.

Further, the business that has actually transpired is pretty paltry: in 1992, Turkey's total trade (imports and exports) with the five republics of Central Asia amounted to a mere $300 million. Nor is it likely to go much higher soon, for the two sides produce many of same goods. Turkey neither offers much of a market for Southern Tier products nor supplies what the Southern Tier most wants to buy.

By late 1992, Southern Tier republics had begun complaining about Turkish activities. For example, the Azerbaijani authorities disliked the fact that Turkish joint ventures were attached not to manufacturing but to - as in the old, bad Soviet days - exporting raw materials. In December 1992 Kazakhstan's ambassador to Turkey accused Turkish businessmen of "lacking the courage to initiate investment," though he may have been confusing courage with capitalization. More broadly, as Patrick Clawson of the National Defense University argues, the Turkish example does not inspire ex-Soviet Muslims.

The "Turkish model" looks rather uninviting to those who see Turkey as at best a second-class economy, with profound problems-a foreign debt that has had to be rescheduled several times in recent decades, a growth record well below that in East Asia, continuing macroeconomic imbalances (budget deficits and inflation), etc.

Assessing Turkey's current economic capabilities, William Ward Maggs holds that it cannot "do much more than ship typewriters and television programs" to the Southern Tier. In Martha Brill Olcott's words, Turkish efforts have proven to be "more air than action." The new "great game" for power in Central Asia, Boris Rumer of Harvard comments, brutally but accurately, "is unfolding not so much among the old colonial powers as among their former minions, many of whom are themselves just emerging from colonial domination and seeking to define their roles."

Then there is the Azerbaijan fiasco. As the Southern Tier republic closest to Turkey both spatially and culturally, Azerbaijan served as a showcase for Turkish efforts to help ex-Soviet Muslims leave the Russian sphere of influence and find their way to stable democracy. But Ankara did little to help Azerbaijan in its war with Armenia. The Turks warned Yerevan in 1992 that Armenia's attacks on Azerbaijan forces "would inevitably affect Turkish politics, and could even destabilize the country." A year later, as Armenian aggression intensified, so did Turkish rhetoric, with Prime Minister Demirel going so far as to warn the Armenians, "If you are enemies of Azerbaijan, so you become enemies of Turkey." Many observers expected that fighting between Azeris and Armenians would spur Ankara to come to the aid of its brethren. Heated words aside, however, Ankara basically stayed out of the conflict; it strenuously asserted that "Not a single Turkish soldier serves in the Azerbaijan Armed Forces" and admitted only to sending humanitarian aid and training Azeri officers. For its part, Baku acknowledged just Turkish deliveries of fabric for its troops' field uniforms and a retired Turkish general of Azeri origins.

The election of Ebulfez Ali Elçibey as president of Azerbaijan in June 1992 brought a passionately pro-Turkish politician to power. Elçibey hung a portrait of Atatürk in his office , appointed Turkish citizens to high positions in his government, and spoke ardently of Turkey as a "light of hope for all Central Asia Muslims and Turks." His comments even took on a maudlin quality, as when he explained how Azeris become "tearful when Turkey is mentioned. These tears are the tears of estrangement and longing of a hundred years." Turks replied to these extravagant statements in kind. For example, President Turgut Özal told Elçibey: "This is your second country and Azerbaijan is our second motherland." When Haydar Aliyev removed Elçibey from power in June and July 1993, however, Ankara did not lift a finger to rescue Elçibey's presidency. Turkish politicians merely pointed out the illegality of Aliyev's rule and fretted about his "Stalinist" methods.

This combination - not protecting Azerbaijan from Armenian predations or swaying Azerbaijan's domestic politics - drastically reduced Ankara's reputation as a force to be reckoned with in the Southern Tier.

Lack of interest. The Western press contains many statements to the effect that Southern Tier countries are looking to the Middle East for a model to follow. In a typical assertion, Colin Barraclough held that the "Central Asians are searching the outside world for a model for change." Middle Easterners also promote this notion. Umut Arik, chairman of the Turkish Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), which doles out Turkish aid to the Southern Tier, contended that the new republics are "in search of a model."

But a close examination of sentiments among the ex-Soviet Muslims suggests they are not looking to the Middle East. To begin with, they recognize the weakness of their neighbors. With some disdain, they dismiss as "second hand" the technology proffered them by Turks and Iranians, pointing out that it really comes from Germany or some other Western country.

Southern Tier leaders also express skepticism about coming under the sway of another state. "We reject foreign influence, whether Turkey's or Iran's, in our lives and politics," Foreign Minister Khudoyberdy Kholiqnazarov of Tajikistan has asserted. "After years of Russian imperialism we just want to live free in an independent country called Tajikistan." Ex-Soviet Muslims have plenty of diurnal problems without getting involved in faraway regions. Falling right back under what Southern Tier residents consider the tutelage of another distant capital holds out few charms for them. And visionary schemes of any sort have little appeal for peoples emerging from decades of corrupted ideology.

Ties to Russia remain strong; indeed, in many respects the independence of the Southern Tier states is more formal than real. And Russia shows keen and growing interest in reasserting its influence over the former Soviet republics (now known as the "near abroad"). To associate too closely with Middle Eastern states, then, could make trouble with Moscow.

Finally, ex-Soviet Muslims take pride in their own accomplishments. They see themselves as no less civilized than their southern neighbors and reject notions that they need to learn from the latter. Where are infant mortality rates lower and literacy rates higher? Who hosts a cosmodome and advanced military industries? And which countries until recently contributed to the Soviet superpower? Southern Tier Muslims feel culturally and technologically at least the equal of Turkey. Azimbay Ghaliyev, a Kazakh demographer, sees the balance this way:

Turkey is a developing country. Internal conditions and internal stability are inadequate; religious and nationalist fundamentalism and powerful Kurd and Arab nationalities are increasingly important factors. The light and food industries and tourism are well developed in Turkey. On the other hand, non-ferrous metallurgy, chemistry, and machinery construction technology are just now becoming established. Sectors such as space research, astrophysics, nuclear physics, mathematical physics, and chemical medicine are mostly nonexistent. They are striving to learn these from us. Likewise, it would be more suitable for us to learn the banking system from the United States, Germany, and Japan. In this area, we must look at the Turkish example with critical eyes.

Symbolic of the ex-Soviet Muslims' pride, Tashkent in August 1992 announced the granting of a hundred scholarships for Turkish students to study in Uzbekistan, signaling that aid will not go in just one direction. At the same time, the Uzbekistanis (and Kyrgyzstanis) took advantage of only some of the two thousand spots awarded their students at Turkish institutions.

Azerbaijan's experience confirmed the hesitations of ex-Soviet Muslims about Turkey in another way. Elçibey's extravagantly pro-Turkish policies and statements led to criticism that he had replaced the Russian "big brother" (starshyi brat) with a Turkish one (agabey). The pro-Turkish program alienated so many constituents that by the time Elçibey faced a military rebellion in June 1993 he lacked a strong base. His old-guard opponents easily overthrew him, brought in communist-era practices, and replaced the Turkish orientation with a Russian one.

Nevertheless, Southern Tier leaders are willing to play along with Middle Easterners - for a price. The Southern Tier urgently needs capital and training; flattery is a small expense to pay for these benefits. As Maqsudul Hasan Nuri puts it, referring to the states of the Southern Tier, "these 'six brides' are going to use all their charms and wiles and guile to extract maximum aid and the best business terms for themselves." The apparatchiks yet running the Southern Tier made their way up the slippery hierarchy of the Communist Party by pleasing their superiors, and they have few scruples about pleasing new potentates. It is simply a matter of adapting their verbiage: democracy takes the place of socialism, Islam replaces atheism, the market replaces central planning, Turkish and Persian languages replace Russian. Reality changes very little, however.

Thus, the deputy prime minister of Uzbekistan had no problem appealing to Turks, "Teach us the Turkish language and culture." Islam Karimov, the tough ex-communist leader of Uzbekistan, referred unblushingly to "the holy land of Iran" on arrival in Tehran. If Turks wish to suffuse their politics with emotions, Southern Tier Muslims happily respond in kind. When Demirel told a Central Asian audience, "Your name will be registered in a golden page in the history of the great Turkic community," Uzbekistan's president replied with a rousing "Long live the unity of Uzbeks and Turks." The right prize will prompt almost any words. On the other hand, these words will cease if suitable rewards are not forthcoming.

Southern Tier Impact on the Middle East

If Middle Eastern states have little influence over the Southern Tier, influence emanating from the latter has greatly affected the Middle East. In the language of social science, the causal arrow goes from Central Asia to the Middle East. Opinion polls confirm this observation. Southern Tier residents consistently show great curiosity in and high expectations of the West and Russia, and much less of both concerning Turks, Iranians, Arabs, and Pakistanis. When asked in January 1992 which country they would like to visit, a representative sampling of almost 900 adults living in the Uzbekistan capital of Tashkent placed the United States a strong first, followed by India, Japan, and Turkey. The same poll revealed that six in ten Uzbekistanis want Western countries to help them "build democracy." In contrast, a sampling of 1,000 Turks in November 1992 revealed very strong interest in Central Asia; for example, more Turks sought social and cultural relations with Central Asia than with Western Europe, the Middle East, or the United States.

Southern Tier independence has already had a variety of consequences for the Middle East. For example, the Iranians had planned to construct a pipeline across Turkey to Europe but scuttled this plan in April 1992, choosing instead to lay the line via Azerbaijan, Russia, and the Ukraine. This change in route (which is yet to be financed) clearly reflected the Iranian rivalry with Ankara for influence in the Southern Tier. Turks understood this change of mind in light of that competition and threatened to retaliate by encouraging Turkmenistan not to build a pipeline through Iran, but instead under the Caspian Sea, then through Azerbaijan and along the Armenia-Iran border. Ankara raised the stakes in August 1993 when it retaliated for Iranian obstructionism by charging 1,600 German marks for each Iranian truck crossing through Turkey. The Turks made it clear that they would rescind the charge if given access to Azerbaijan via Iranian territory.

Most consequences are larger and vaguer than this, however. The remainder of this chapter looks at two especially dangerous theaters, the Azeri and the Tajik-Pashtun, and assesses the ways in which they can disrupt the Middle East. Then it considers Turkey and the other Middle Eastern states affected by Southern Tier independence. It concludes with some speculations for the long-term future. First, however, some background on the Southern Tier.

Background

Muslims of the former Soviet Union number some fifty-five million and live primarily in six southern republics, one in the Transcaucasus (Azerbaijan) and five in Central Asia. Muslims make up a majority in all these Southern Tier republics except for Kazakhstan, where they constitute just 42 percent of the population (Russians constitute about 36 percent). Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have by far the largest populations (20.7 and 16.8 millions, respectively), followed by Azerbaijan (7.2 million), Tajikistan (5.4 million), Kyrgyzstan (4.4 million), and Turkmenistan (3.7 million).

Fifty million residents of the Southern Tier speak various forms of Turkic, some quite intelligible to a resident of Istanbul, others not. The languages of Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan present him with few troubles, but Kazakh is another matter. A native of Istanbul can communicate basic ideas in Kazakh but little more. Conversing requires several months of residence and study. While it is true, as Paul Henze of the RAND Corporation points out, that su means "water" from the Adriatic to China, most other words change across that vast distance. The gradations of difference might make it possible, however, for the Kazakh to pass on his message via a Kyrgyz to an Uzbek, to an Azeri, then to the Istanbul native.

The other five million Muslims of the Southern Tier speak Tajik, an Iranian language intelligible to Tehran's residents. Tajik closely resembles Dari, the Persian language of Afghanistan.

Russian conquest of the Southern Tier began with the conquest of Azerbaijan by 1828. The tsar's forces then needed another forty years to conquer Central Asia, from 1847 to 1885 - which was about the same time as the British and French empires reached their maximum extents in Africa and Asia. Indeed, Russian settlement in Central Asia resembled that of the British in Rhodesia or the Portuguese in Angola. But it most closely mirrored French control of Algeria. Algeria and the Southern Tier are both lands of ancient civilization and high Muslim civilization. Like the French in Algeria, Russians settled in Central Asia in substantial numbers. They built new European cities alongside the old Muslim ones. They appropriated the best land and monopolized the key jobs. The main differences are three: Russians used far more brutal methods than the French or any other European colonial power; blue water divides Algeria from France, while the Southern Tier is connected by land to Russia, thereby obscuring the colonial quality of Russian rule; and the Soviets gave colonialism a modern cast, turning it into a seemingly altruistic enterprise for the sake of "younger brothers" in the Southern Tier.

During the Soviet period, and especially before 1980, this colonized Muslim body experienced a nearly total isolation from its coreligionists to the south. With very few exceptions, borders were completely closed. This meant, for example, that travel between Baku and Tehran, just 350 miles apart, required going via Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport, a detour of 2,400 miles. (In American terms, that is like going from Boston to Baltimore via Houston.) Moscow manipulated scripts to reduce communications, imposing the Cyrillic alphabet to distance Soviet Turcophones from the Latin script used in Turkey and the Arabic script used elsewhere in the Muslim Middle East. Bombarded by Marxism-Leninism, Soviet Muslims could not participate in the culture of Islam. Only a handful of them made the pilgrimage to Mecca or studied at Islamic institutions of higher learning in Cairo or Fez. At the same time, glossy propaganda featured peoples called "Muslims of the Soviet East" and a steady parade of third world delegations was routed through Tashkent to witness the wonders of Soviet civilization in Islamic garb.

Seventy years of isolation (and one hundred fifty years of Russian dominance) came abruptly and unexpectedly to an end in late 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union. One anecdote captures the astonishing speed of this transformation: On his arrival in Turkey on the morning of 16 December 1991, President Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan received no official honors, for Ankara viewed his republic as part of the Soviet Union; that very afternoon, the Turks recognized all the Soviet republics as independent states, changing Karimov's status. On leaving Turkey three days later, he received the 21-gun salute reserved for heads of state.

Liberation and independence came not only quickly, but also nearly unasked for. Soviet Muslims did very little to bring about the end of communism or to break up the U.S.S.R.; they simply benefited from actions taken elsewhere. Bakhadir Abdurazakov, a Soviet ambassador of Uzbek origins, captured the general astonishment this way: "The disintegration of the empire was God's gift. Really, it is enough to make one believe." Not only were the Southern Tier leaders not involved in winning their independence, but in many cases they did not even welcome it, remaining loyal to the old order longer than did the Russians themselves! Kazakhstan's government, for example, never declared its withdrawal from the Soviet Union. As Martha Brill Olcott writes, "Few peoples of the world have ever been forced to become independent nations. Yet that is precisely what happened to the five Central Asia republics."

These unusual circumstances explain why the new Southern Tier governments were so woefully unprepared for sovereignty. Abdurrahim Pulatov, leader of the opposition in Uzbekistan, ruefully looks back on this experience and declares, "Independence came to Central Asia too quickly and too easily." A Central Asian economist expressed this even more strongly, comparing the new republics to "a baby who has lost his parents." The apparatchiks who still make most decisions knew how to execute economic and social orders from Moscow, not how to incubate a free market or solve ethnic problems; and they certainly have little experience in making foreign policy.

The abruptness of Central Asian independence spawned many problems. Thus far, two stand out as the most dangerous, one concerning Azeris, the other Tajiks.

TWO DANGEROUS THEATERS

Azeris and Tajiks have several features in common. Both populate and control small republics at the edge of the former Soviet Union. Both connect linguistically and religiously to several neighboring countries, and Iran in particular. Both are in the throes of violent upheavals that threaten their entire regions.

The Azeri Theater

While the travails in the Caucasus impinge on many countries - Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Turkey, Iran - they center on Azerbaijan for two main reasons. Twice as many Azeris live in Iran as in Azerbaijan, raising acute tensions between Tehran and the newly independent government in Baku; and Azerbaijan's war with Armenia tempts Turkey and Iran to intervene, with potentially cataclysmic results.

A map of "north" and "south" Azerbaijan dating from the Elçibey era. |

Iranian Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan is a nation divided in two, with the independent Republic of Azerbaijan (capital, Baku) in the north and the traditional Iranian province of Azerbaijan (capital, Tabriz) in the south. A mere 6 million Azeris live in independent Azerbaijan, versus some 12 million in Iran (where they constitute by far that country's largest ethnic minority). Moscow conquered northern Azerbaijan by 1828; from then until January 1990, the two halves of Azerbaijan had no serious hope of uniting, except in 1945-46 period, when Stalin controlled Iranian Azerbaijan.

Baku's emergence as an independent capital has fundamentally changed the equation, inspiring Tabriz to dreams of independence and union. With the election of Ebulfez Ali Elçibey as president of Azerbaijan in June 1992, nationalist Azeri ambitions to unite Azerbaijan increased dramatically, only to decline a year later when Elçibey lost power. Elçibey referred to his country as "northern Azerbaijan" and regularly called for the cultural autonomy of Azeris living in Iran, the uniting of the Azerbaijani region of Iran with his country, and even the overthrow of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Especially during the Soviet era, Azeris living in Iran had little desire to join their northern confrères. ("When the Tabriz residents interviewed in 1952 were asked about sentiment for union with Azerbaijanis now in the Soviet Union, their... unanimous response was one of incredulity.") Even today, they feel unsure of their identity - Turcophones who happen to live in Iran or Iranians who happen to speak Turkic. But the emergence of an independent Azerbaijan has an impact. If ex-Soviet Azeris are politically independent of Moscow, why do those living in Iran remain subject to Tehran? Nationalist appeals coming from Baku resonate. Northerners fleeing their troubles move south and take with them nationalist ideas. They win rapturous receptions in the south, especially when the two sides connect culturally (for example, through poetry) or politically (through anti-Armenian slogans).

Even with Elçibey out of power, the Iranian authorities rightly worry that independent Azerbaijan will eventually try to wrest away Iranian Azerbaijan. Loss of this area would have several major consequences for Iran. It would reduce the country's population by about one-fourth. It would provide a land bridge between Turkey and northern Azerbaijan, now separated by Armenia, strengthening the Turcophone bloc to the north. It might inspire Iranian Kurds and Turkmens (also known as Turkomans) to break from Iran to join their brethren across the border, leading to a breakup of the Iranian polity.

To protect against these developments, Iranian leaders strongly denounced Elçibey and helped the opposition forces in his country. They moved Nakhichevan, an autonomous and geographically separate portion of Azerbaijan, toward the Iranian orbit by maneuvering politically and building up trade relations. They helped Haydar Aliyev topple Elçibey in June 1993. More defensively, they split Iranian Azerbaijan into two provinces (Sabalan and East Azerbaijan, with capitals in Ardebil and Tabriz ), in an apparent effort to reduce a sense of Azeri nationhood. These efforts succeeded in containing Azeri nationalism to the point that Tehran felt confident enough to relax long-standing prohibitions against Azeri Turkish in 1992, allow an Azerbaijan consulate in Tabriz in June 1993, and open a direct Tabriz-Baku flight one month later. But it could yet lose control.

War with Armenia. War between Azerbaijan and Armenia poses even greater dangers. Fighting began in early 1988 when the Armenian leadership in Yerevan, sensing the decline of Moscow's power, launched a military campaign to seize control of Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous area populated by Armenians but located within Azerbaijan's borders. Azeris resisted, and the conflict escalated into a brutal struggle of mutual sieges, embargo, and massacre. While Armenians have suffered terribly from hunger and cold, their forces have fared well on the battlefield; by late 1993, they held nearly 20 percent of Azerbaijan's territory.

Turks have a strong visceral sympathy for Azeris, an emotion that Azeris reciprocate. The two speak almost the same language and have a history of close relations. Symbolic of this, Azeris (alone of the ex-Soviet Muslims) have actually taken steps to adopt the Latin alphabet, have chosen to be represented abroad by Turkey, and have asked Ankara "to be a center for our country's relations with the outside world." They proclaimed an adherence to "Atatürk's way." Also, Turks and Azeris share a history of conflict with Armenians. In addition, Turkey counts many citizens of Azeri origins.

Not surprisingly, Turkey's leaders feel strong popular pressure to join the battle on Azerbaijan's side. Mustafa Necati Özfatura, a Pan-Turkic nationalist, pushed for alliance with Azerbaijan, stating that "an attack on Azerbaijan would be considered an attack on Turkey." Özal called for Turkey to help Azerbaijan fight the Armenians. A May 1992 poll showed one-third of the Turkish electorate supporting armed intervention. Pressure also came from Azerbaijan, where leaders use a kind of code, calling on Turkish support to help the Azerbaijanis "consolidate" their independence - that is, control the territories contested by Armenians. Prime Minister Tansu Çiller subsequently warned that "If one spot of Nakhichevan is touched," she would ask parliament to authorize war on Armenia.

Although 1,600 Turkish military experts were sent to Azerbaijan (where they were joined by 200 pan-Turkic militants of the Nationalist Action Party), Turks generally maintained what Demirel characterized as a "coolheaded approach," resisting the temptation and the pressure to intervene. They did so for very good reasons. In the first place, Turkey needs Armenia for access to Azerbaijan and Central Asia - be it transportation links or oil pipelines. Second, Turkey has enough problems with neighbors (Aegean islands and Cyprus with Greece, ethnic Turks with Bulgaria, water with Syria, Kurds with Iraq and Iran) without needing another hostile state. Third, siding with Azerbaijan could jeopardize Turkey's carefully nurtured relationship with the U.S. government. When arguing for restraint, Demirel explicitly acknowledged the danger of an erosion in his country's international position:

When I was received by U.S. President Bush in Washington on 11 February [1992], I told him that if the United States and Western countries back Armenia in this conflict, then we will have to stand by Azerbaijan, and this will turn into a conflict between Muslims and Christians that will last for years.

On another occasion, Demirel commented, "The world will move against Turkey if we close all our doors and move against Armenia." To this, Foreign Minister Hikmet Çetin added: "The people in the United States would create an uproar if the Armenian people die of hunger and cold."

Fourth, the Caucasus could explode if Turkey joined Azerbaijan's war against Armenia. Russia, Iran, and some Western countries might respond by assisting Armenia. Russia, the Armenians' traditional protector, explicitly raised the possibility of intervention. In a May 1992 statement, Marshal Yevgeny Shaposhnikov of the Commonwealth of Independent States warned that, were Turkey to join the conflict, "we shall be on the brink of a new world war." While exaggerated, this threat did have a sobering impact in Turkey. For good measure, the Armenian foreign minister two days later threatened to take recourse to its CIS security pact if Turkey intervened militarily in the Caucasus. To prevent a Russian-Turkish confrontation, Çiller traveled to Moscow in September 1993 and the two sides set up a hot line.

These reasons impelled Turkey's leadership to exercise admirable restraint toward Armenia. It has even made goodwill gestures, such as supplying one hundred thousand tons of grain, thus helping that country circumvent the economic blockade imposed by Azerbaijan. More surprising yet, Turkey contracted in November 1992 to sell 300 million kilowatt-hours of electricity to the Armenian energy grid at a lower rate than that paid by Turkish consumers. (The electricity was to be supplied, ironically, via power lines installed during the 1980s to carry Soviet electricity to Turkey.) Foreign Minister Çetin justified this aid by arguing that it shows "Ankara is not Yerevan's enemy." In addition, Turks worried that, cut off from outside supplies of energy, the Armenians would reactivate their Chernobyl-style nuclear reactor at Medzamor. But Azeris vehemently objected to this sale, calling it a "stab in the back " and a "betrayal" of their cause, and their Turkish partisans protested loudly. In the end, the Turks sent heating fuel to Armenia , though these supplies (and all other humanitarian aid) were cut as a result of Armenia's breaking out of the Nagorno-Karabakh area in March 1993 and capturing large amounts of Azerbaijani territory.

Armenia also had compelling reasons to maintain good relations with Turkey. Having lost its historic Russian protector and being nearly surrounded by Turcophone Muslims, it needed to get along with the strongest of its neighbors. Also, Turkey provided its best access to the outside world. In gratitude for Turkey's goodwill gestures, the Armenians offered "to open all our roads" for transporting humanitarian aid to Azerbaijan. To encourage Turkey to remain neutral, Yerevan ignored the vehement anti-Turk sentiments of its own population and downplayed the issue of genocide during World War I. When asked about the latter, Deputy Foreign Minister Arman Kirakosyan replied, "Armenia wants to look forward in its relations with Turkey. Genocide does not concern the Armenia government. ... Any incidents took place before the republic in Turkey was established." Yerevan even asked its diaspora brethren, much to their annoyance, to ease up on the anti-Turkish campaign. Strangely, then, the Caucasus war has so far led to an improvement in Turkish-Armenian relations, a testimony to the maturity of the leaders on both sides, and it enhanced Turkey's lagging reputation in the West.

Unfortunately, the strength and patience of moderates has limits. Should atrocities against Azeris continue or Armenians succeed in taking more and more of Azerbaijan's territory, Turkey could intervene militarily, with disastrous results for nearly everyone. On the Armenian side, continued war, isolation, and impoverishment reduces the appeal of President Levon Ter-Petrosian's middle course, while winning support for the extremist Dashnak Party.

As for Tehran, it formed a quasi-alliance with Armenia, helping this Christian nation against its Muslim neighbor. This may explain why Armenian forces pushed their offensive toward Azerbaijan's border with Iran in August 1993. Tehran moved extra troops to the area of its border with Turkey and sought to undermine Azerbaijan's control of Nakhichevan. The Iranians did so because they share key concerns with Armenians about Turkey and Turcophone unity, though for different reasons. They also can help each other. For example, Armenia's leaders offer themselves as a bridge to the West and make their scientists available for Iranian employment. James M. Dorsey claims, with only some exaggeration, that the Armenian-Iranian alliance "could reshape the political map of the Middle East."

Because fighting in the Caucasus so closely touches on Turkish and Iranian interests alike, it could embroil them in a conflict neither seeks. "If there is to be a major war between these two," Maggs writes, "it will come in Armenia and Azerbaijan, where their interests will most actively collide." In sum, while Azerbaijani independence creates problems for both Turkey and Iran, it also presents opportunities for the former.

The Tajik Theater

Central Asia is a cauldron of real and potential troubles. Afghanistan's civil war began in 1979 and continues on; Tajikistan's civil war began in 1992. Border problems could cause as much trouble in Central Asia as in the Caucasus; ten territories are in contention. One observer calls these a "time bomb" for the region. Religious, ethnic, and ideological problems afflict the region. Religion's cutting edge concerns Sunnis and Shi'is. Leading ethnic groups include Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Pashtuns. The first three came to blows in Osh, a corner of the Ferghana Valley. The second three are engaged in Afghanistan. As for ideology, fundamentalist Islam constitutes the main force. It comes in several varieties (Khomeinist, Pakistani, Tajik). Communism used to offer an alternate vision, but with the collapse of the Soviet Union, that is now reduced to the common background of a self-interested group that benefited from the old system.

These conflicts threaten the stability of the entire region between Iran and China, but we concentrate here on the impact on Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Afghanistan. As in the Caucasus, ethnic mixing bedevils politics in the Tajik-Pashtun theater. From the birth of Afghanistan in the eighteenth century until the Soviet invasion, Pashtuns (also known as Pathans and Pukhtuns) constituted more than half of the population and ruled the country. As a result of massive emigration during the 1979-89 war, mostly to Pakistan, today they make up just one-third of Afghanistan's population, or about five million. In contrast, Pakistan now hosts twice that number of Pashtuns, though they constitute less than 10 percent of Pakistan's population.

Similarly, more Tajiks live in Afghanistan (about 5 million) than in Tajikistan (about 3.3 million), although they make up a smaller percentage of the population in the former (35 percent vs. 62 percent). Additionally, some million Tajiks live in Uzbekistan, 100,000 in Kazakhstan, and 30,000 in the Sinkiang province of China.

These figures point to two main sources of trouble. First, the imbalance in populations (Afghanistan hosts more Tajiks than Tajikistan, Pakistan hosts more Pashtuns than Afghanistan) is a sure-fire recipe for instability. As elsewhere (Iran hosts more Azeris than Azerbaijan, more Turkmens than Turkmenistan; Jordan hosts more Palestinians than "Palestine"), a national group that lives primarily outside its own primary region is virtually foreordained to irredentism.

Second, Tajiks hope to take advantage of their new numerical strength in Afghanistan to wrest power from the Pashtuns. Each of these peoples constitutes about one-third of Afghanistan's 15 million inhabitants; the rest of the population divides among Hazara (about 15 percent), Uzbeks (about 12 percent), and Turkmens (about 5 percent). Afghanistan's civil war has produced military leaders from the two largest ethnic groups and from the Uzbeks.

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the leader of Hezb-i Islami, represents the Pashtun determination not to cede power in Afghanistan. As is so often the case with nationalist leaders, he was born outside his ethnic heartland, in the predominantly Tajik area of Kunduz. Though widely seen in the West as a fundamentalist Muslim extremist, Hekmatyar's record reveals him to be an opportunist of the first rank. The Pakistani government, working through its Interservices Intelligence (ISI), found Hekmatyar an ideally pliable agent of its power during the war and used him as a way to bring the mujahidin under its control.

Ahmed Shah Mas'ud, the hero of the anti-Soviet resistance and defense minister of Afghanistan, represents the ethnic Tajik intent to win power from Pashtuns. Although an immensely capable leader who united the Tajiks under his command and made common cause with Uzbeks, he has been unable to extend his ministry's mandate to the Pashtun areas; also, he has repeatedly lost ground to Uzbeks. Indeed, Mas'ud could not even hold on to Tajik regions. Again, Mas'ud's reputation in the West belies reality; though widely seen as religiously moderate, he is the genuine fundamentalist.

General Abdurrashid Dostam ("the most powerful man in Afghanistan today") represents the interests of the largest people in Central Asia, the Uzbeks. And, as befits a former military leader fighting for the Soviet-sponsored regime, he represents the forces of anti-fundamentalism. For both these reasons, Dostam has particularly close relations with Karimov of Uzbekistan; his family lives in Tashkent and the two leaders have discussed his going independent. This is a realistic possibility, for, based in the northwestern Afghan city of Mazar-i Sharif, Dostam has managed to carve out for himself "virtually a separate state" or "a state within a state." Indeed, Mazar-i Sharif already boasts consulates of Iran, Uzbekistan , and Pakistan.

Rival forces have thus effectively divided Afghanistan into three zones: Pashtuns under their chieftains and Hekmatyar control the south of Afghanistan, Uzbeks under Dostam rule the north, and the government of Iran enjoys predominant influence in the west, where it controls a grouping of Shi'is, the Hezb-i Wahdat. (Tajiks under Mas'ud have been restricted to the northeast, largely squeezed out of the country's power politics.) Each of these powers looks to bring its region of Afghanistan in closer association with a state beyond the border-Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and Iran, respectively. (And the Tajiks look to Tajikistan.)

The civil war in Afghanistan directly affects surrounding countries. For example, the fall of Afghanistan's President Najibullah to fundamentalist Muslims in April 1992 inspired fundamentalists in Tajikistan just a month later to bring down their own Communist ruler, Rakhmon Nabiyev.

Afghanistan's northern border has been highly porous for a decade. During wartime, official Afghanistan forces virtually ignored the formal lines separating their country from the Soviet Union, and the mujahidin imitated them, laying mines in Soviet territory and recruiting among Muslims in the Soviet Union. The mujahidin also directed radio broadcasts to the north. Today, the old border hardly exists, as Dostam's ethnic Uzbek militia routinely crosses into Tajikistan to protect fellow Uzbeks there. The authorities in Uzbekistan blame the proliferation of weapons among ethnic Tajiks in their country on smuggling from Afghanistan. Going in the other direction, over 100,000 Tajiks have braved the frigid waters of the Amu Darya River to flee the war in Tajikistan and seek refuge in Afghanistan. On arrival, the young men among them are armed and some return to battle the government in Tajikistan.

This disappearing border gives substance to the hope of many Tajiks, including Mas'ud, to join northern Afghanistan and Tajikistan in a unified Tajik state. As my colleague Khalid Duran notes, the process is fairly far along: "the reunification of Tajikistan - one Afghan, the other formerly Soviet - has progressed considerably since 1988, even though it did not make headlines as Germany did." In all likelihood, such a state would enforce an extreme fundamentalist Islamic vision of society comparable to that in Iran-but in this case Sunni.

The fate of Tajikistan influences the course of events in Afghanistan, which in turn influences politics in Pakistan. To the north, Tajikistan influences Uzbekistan, which influences Kazakhstan, which has a potentially major bearing on Russia. In a sense, then, Tajikistan stands at a pivot, capable of creating problems from the Indian Ocean to the North Pole. For these reasons, Boris Rumer rightly suggests that a Greater Tajikistan "must be a nightmare for [Uzbekistan's President Islam] Karimov. But such prospects ought to disturb [Russia's President Boris] Yeltsin as well. Indeed, such prospects ought to be unsettling for Western states."

Peace and stability in the region depend in large part on Afghanistan, and its future will be determined largely by developments in Tajikistan. Protracted civil war in Tajikistan means Central Asia will burn.

Pakistan. Conceptually, Pakistan lies distant from Central Asia. Geographically, however, it is a near neighbor. Pakistan's capital city, Islamabad, is closer to Tashkent than to its own port city of Karachi; Lahore is closer to Dushanbe than to Karachi. Pashtuns and other peoples of the country's north look more to Central Asia for trade and culture than to India.

Pakistan has substantial interests in Central Asia. Fundamentalist Muslims from Pakistan have their own variant of Islam to promote; the radical group Tabligh-i Jama'at is especially active in Central Asia.

As other doors have closed, Central Asia has taken on major importance as a place for skilled Pakistani emigrants to exercise their talents. They operate as traders, professionals, and executives in Central Asia, a culturally familiar environment in which they feel at ease. As Russians departed, Pakistani entrepreneurs quickly found niches for themselves, especially connecting Central Asia to the outside world. They opened banks and hotels, trained business personnel, and established an airline. They work as doctors and college instructors. In one display of raw financial power, Pakistanis responded to a request from Kazakhstan's prime minister by raising a $100 million loan within three days.

Yacub Tabani, a young entrepreneur, may head the list of Pakistanis active in Central Asia. He helped set up Uzbekistan Airlines and provides management assistance to nearly all the new airlines of the region. Tabani handled fertilizer, chemicals, and cotton for the governments; he set up garment and cigarette factories; and he built a hotel in Tashkent.

Finally, the Pakistan state has a perceived need to develop strategic depth against India; Central Asia offers geographic vastness and a sizable population. This defensive concern may imply grand nationalist ambitions, as Hafeez Malik of Villanova University explains: "Pakistanis have started to speculate that Pakistan's natural habitat includes Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and the Central Asia Republics." Sometimes called "Islamistan," this region gets counterpoised against the Arabic-speaking south.

The Pakistani government has tried hard to establish close relations with the Southern Tier states through diplomacy and transportation links. By late 1991, Islamabad had offered unconditional support for Azerbaijan's cause against Armenia. It recognized the Southern Tier republics just days after Turkey did, then sent a large delegation to Central Asia to establish cultural and economic ties. The Pakistani authorities strenuously tried to establish special relations with Kyrgyzstan. To win favor in oil-rich Turkmenistan (dubbed by some "the second Kuwait"), Islamabad offered $10 million in credit.

Pakistan's government plans ambitious transport connections to Central Asia. It has proposed building a railway across Afghanistan to link up to the trains of the former Soviet Union. A new road along the Amu Darya River connects Mazar-i Sharif in north Afghanistan with Chardzhou, the second largest city in Turkmenistan , but unsettled conditions have much reduced traffic. For now, once-weekly PIA flights to Tashkent and Almaty (Kazakhstan's capital) constitute the sole transportation link between Pakistan and Central Asia. This air connection does not suffice, however; for Pakistanis fully to exploit the Central Asian connection, they need a land route via Afghanistan.

A land link in turn implies the need for peace in Afghanistan, which partially explains why Pakistan's policy dramatically changed in late 1991, when Islamabad abandoned Hekmatyar. (Another imperative for seeking a settlement was to induce the Afghan refugees to go home.) With Hekmatyar in power in Kabul, the Pakistani government would have gained its long-sought strategic hinterland. But Islamabad diminished its support for Hekmatyar because it had an eye on Central Asia. As Central Asia beckoned, using Hekmatyar to establish a military hinterland lost priority.

In sum, Central Asia's independence has fundamentally altered the civil war in Afghanistan, adding new elements, and altering Pakistan's calculations.

IMPACT ON TURKEY

"Turkey is like a strong castle in a tempestuous sea," President Özal confidently declared in late 1991. But the abrupt independence of tens of millions of Muslims in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Balkans has caused some leakage in the Republic of Turkey. The stolid pro-NATO course of recent decades is giving way to an unfamiliar exhilaration and confusion. The Southern Tier's independence has affected politics in Turkey, with large and unpredictable consequences, making this country particularly deserving of attention.

Changed Politics

Thanks to the Soviet bloc's collapse, a new and excited tone pervaded the Turkish body politic in 1991 and 1992. "Heady days for Turks, these." The Turkish population got engaged in foreign policy in new ways and the government adopted an unheard-of activism. Mainstream politicians articulated ideas about Pan-Turkic nationalism that had been the exclusive preserve of the fringe right. In all, the situation led Turks to see themselves as a more active force in the world.

Foreign policy activism. For decades, Ankara avoided taking foreign policy initiatives, preferring to follow its allies. This held doubly true in policy vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. The Soviet collapse inspired Turks quite suddenly to see themselves as a major regional power, relatively stable, militarily potent, and economically strong, roles enhanced by the Turkish role in Operation Desert Storm. They variously portrayed Turkey as the natural leader of the Balkans, the Black Sea area, the northern Middle East, and world Turcophones. The Turkish decision of mid-December 1991 to recognize all the republics of the former Soviet Union as independent states, possibly the most daring Turkish choice in decades , marked the emergence of this new confidence. One newspaper commentary viewed this as the first time ever Turkey had acted "without considering the decisions of other countries."

Nineteen ninety-two also saw a stunning series of regional initiatives. President Turgut Özal announced that "Three important areas, the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Middle East, have opened in front of Turkey," and the government followed up on this vision. Ankara conceived the Black Sea Economic Cooperation Zone and hosted a summit meeting of member states in June. It hosted a summit conference of Turcophone leaders in October, not coincidentally on Turkey's independence day. And it hosted a Balkan summit in November. Further, the Turks infused new life into the Economic Cooperation Organization, which links Turkey to Iran, Pakistan, and other states. Perhaps most interesting were the attempts to reach out to long-time adversaries (Greece, Armenia, the Kurds), inspired both by a practical need to improve the country's diplomatic position and international reputation and by a sense of power that implied largesse.

Turkish diplomacy took on a slightly frenzied quality - new embassies, huge delegations traveling to many countries, and lots of visitors. On a single day in January 1992, for example, no fewer than three presidents - those of Albania, Serbia, and Azerbaijan - found themselves in Ankara. Some guests came from places only Ankara cared much about, such as Tatarstan. After years of acceding to Arab wishes, Ankara boldly invited Israel's President Chaim Herzog to participate in the quincentennial anniversary of the arrival of Sephardic Jews from Spain in 1492.

The 1993 dispatch of a Turkish unit to Somalia and the appointment of a Turkish general to the mission constituted a small but revealingly far-flung endeavor of a sort that would have been unlikely in previous years.

But then the mood passed almost as quickly as it arose. An October 1992 summit of Turcophone leaders in Ankara signaled the troubles ahead; Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev refused to go along with the Turkish agenda out of concern not to upset Moscow. The June 1993 collapse of Elçibey's government finally punctured the romance with the new states. Turkish leaders realized the limits of their influence and retreated to a more passive foreign policy.

Ethnic identification. In this century alone, substantial numbers of immigrants have come from Bosnia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Iraq, Iran , the Russian Empire/Soviet Union, Afghanistan, and China. Numbers are hard to come by and are probably exaggerated: Turks of Azeri origins, for example, are said to number six million, while nearly ten million Turks trace their origins to the Balkans. Taking inflated figures into account, the descendants of these immigrants probably number about twelve million, or one-fifth of the Turkish population.

While immigrants assimilated into Turkish life, they yet remembered their ancestry. During the Cold War, the authorities in Ankara suppressed connections to the old countries for the simple reason that most of them had communist governments. The Soviet bloc's collapse ended that suppression and raised the specter of heightened ethnic consciousness within Turkey. As Caucasian peoples like the Abkhaz, Chechen, and Ossetians asserted their identity, Turkish citizens of such origins found their ethnic affiliations newly important. Graham Fuller notes that "In 1991, for the first time ever, Turks began to start talking about their own various geographic origins as Turks from diverse areas."

In one case, that of Bosnia, an actual ethnic lobby emerged in 1992. Serbian efforts at "ethnic cleansing" suddenly gave the four million Turkish citizens who trace their origins to Bosnia (twice as many as the Muslims in Bosnia itself ) a special political cause of their own. From the time the war began in early 1992, "they lived with the rhythms of combat in the ex-Yugoslavia, crying for the deaths, indignant about the general indifference for their former patrimony, and trying to soften the lot of refugees stranded in the former Ottoman capital." Folk dancing gave way to refugee absorption efforts. Özal referred to Balkan immigrants creating a "bridge of obligation" between Turkey and their lands of origin. Even the loss of the Serbo-Croatian language did not dim the sense of ethnic solidarity. The mother of Mesut Yilmaz, a former prime minister, came from Bosnia, which helps explain why he was especially vocal on the situation in ex-Yugoslavia. Indeed, Çetin repeatedly mentioned the Bosnian element as one of the reasons his government took special interest in former Yugoslavia.

This fracturing of the Turkish body politic seems likely to continue and to gain in importance.

Worries about immigration. Turmoil in the Balkans, the Caucasus, and Central Asia sent waves of emigrants into Turkey. The Bulgarian campaign of assimilation in the late 1980s prompted 320,000 of its Turkish population to move to Turkey. (With the fall of the communist regime, however, half of these returned to Bulgaria.) In 1992 the Turkish assembly unanimously accepted 50,000 Meskhetian Turks from southern Georgia and indicated a readiness to take in the Akhista (or Akhaltsikhe) Turks of Kyrgyzstan. By November 1992, 15,000 Bosnians had newly arrived in Turkey, of which fully 14,000 settled near relatives. Serbian aggression could cause these numbers to multiply many times; Muhammad Cengic, the deputy prime minister of Bosnia-Herzegovina, announced in May 1992 that about one million Bosnians hoped to emigrate to Turkey.

Like Germans, many Turks feel "the boat is full" (that is, their country has reached full capacity) and actively try to discourage future immigrants by subsidizing them in their places of origins. Ankara is explicit about this: "We aim to provide incentives for Turks to stay where they were born," acknowledged Minister of State Orhan Kilercioğlu. Toward this end, it provides courses on marketing, management, and public administration, and it encourages Turkish businesses to invest in Bulgaria.

Changed Ideas

In the course of establishing the Republic of Turkey, Kemal Atatürk explicitly renounced two types of claims: to form a union with distant Turcophones and to regain the lost Ottoman Empire. His doctrine of disengagement from international affairs ("Peace at home, peace in the world") guided Turkish politicians for seventy years. But the collapse of the Soviet bloc has suddenly opened the possibility of a more ambitious foreign policy. Some Turks have thought through the possibilities of Pan-Turkic nationalism and reasserting Ottoman connections. Together, these ideas have created a new sense of Turkey's importance in the world.

Pan-Turkic nationalism. Pan-Turkism, the belief that Turkic speakers from Albania to the farther reaches of Siberia form a single people and should form some kind of union, has been rediscovered. Extremist figures like Alparslan Türkeş of the Nationalist Movement Party (MCP) found themselves relegated to virtual irrelevance during the era of Soviet strength. But in 1992 his call for Turcophone countries to unify on the basis of "Unity in language, idea, and work" found a new, larger audience.

Süleyman Demirel. |

Returning from a tour of the Turcophone republics: "My head is turning. I am very excited."Meeting a leader of the Crimean Tatars: "You were never alone, and you are not alone now; we are all together."

Addressing an audience in Kazakhstan: "Your name will be registered in a golden page in the history of the great Turkic community."

Dedicating a new bridge between Turkey and Nakhichevan: the bridge meant "the two countries became one again."

Demirel announced that "a new Turkic world has emerged" or even more ambitiously, "a new world has emerged and a new map is taking shape." He proclaimed that Turcophones inhabit an area of ten thousand square kilometers and noted that "Five new flags with crescents have been added to Turkey's crescent-and-star flag. The great Turkic world extending from the Adriatic to the China Sea should intermingle." Demirel enjoyed his new role as chief Turcophone leader. After Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan called him "big brother" (agabey), a highly pleased Demirel often repeated this title.

Of course, others shared Demirel's excitement about Turkey's Turcophone hinterland. "We were all alone; now there are five others," a senior Turkish official explained. To which an intellectual added: "It has been a great thrill for Turks to realize that they are no longer alone in the world." This thrill, more than dreams of glory, lay behind the statements of Demirel and other politicians. It's also important to underline that these statements did not have operational consequences.

Neo-Ottomanism. Nostalgia for empire grew noticeably with the Soviet collapse. After three generations of living the prosaic reality of the Turkish Republic, memories of the Ottoman Empire revived and appear to exert a strong, if slightly illicit allure. Dreams of recapturing the grandeur of the old empire found new expression. Çengiz Candar, who dubbed these sentiments "Neo-Ottomanism," stated, "The time has come to reconsider [Atatürk's] policy. We cannot stick to the old taboos while the world is changing and new opportunities are arising for Turkey. We have to think big."

Many in Turkey echoed this view. Özal announced that "Current historical circumstances permit Turkey to reverse the shrinking process that began at the walls of Vienna [in 1683]." He saw the inhabitants of former Ottoman lands outside Turkey as "children of those who yesterday were our countrymen and the kinsmen of our present countrymen." Re-establishing relations with them is "a natural right and duty." Özal asked, "How could it be otherwise, when we have lived 800 to 900 years together and have been cut off from each other only for the last 70 or 80 years!" Nur Vergin of Bilkent University eloquently captured the sense of longing for empire:

Place names that we sealed away in our subconscious as a result of collective amnesia and which we tried to remember as ordinary geographic areas have begun to reappear in our daily lives: Bosnia, Macedonia, Kurdistan, the Caucasus, and beyond that, Transoxiana [i.e., Central Asia].

Even a Pan-Turkic nationalist like Özfatura incorporated elements of Neo-Ottomanism. On the grounds that the former Ottoman subjects look to Turkey as their liberator, he called on Turkish troops to intervene in Nakhichevan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Macedonia.

Turkey's importance. Turkish politicians, with Süleyman Demirel again leading the way, made audacious statements about Turkey's new importance. Demirel asserted that "The presence of an additional five flags beside the star and crescent boosted our prestige and that of the Turkic republics." "A new world is being born," he declared, "and Turkey is a window on it.... This is a centuries-old dream." "Everyone has to take Turkey more seriously," he told Azerbaijanis in Baku. In part, the prime minister premised these assertions on economics. "When we take a collective view of the economic potential of our [Turcophone] region we can see that it is one of the world's most promising regions.... if we pool our resources then there is no obstacle we cannot surmount." Demirel let his imagination get carried away when he declared that "the oil and natural gas reserves in Central Asia and the Caucasus are bigger than all the world's reserves," an obviously false assertion.

Nor was Demirel alone in these grandiose declarations. Özal asserted in his 1993 New Year's message: "Turkey's region is the most critical region in the world." The writer Attila Ilhan stated, "Turkey can extend its region of influence all the way to the Yellow River [in China]." Husamettin Cindoruk, speaker of the parliament (the Turkish Grand National Assembly), announced that "Turkish unity will bring peace, tranquility, and stability to the world." In perhaps the most extravagant statement of all, Kamran Inan, a minister of state, averred that "Turkey is a candidate to be the strongest state in the West in the period following the year 2010."

Turks not only made lofty statements about the future, but sometimes convinced themselves that Turkey had already attained more than was the case. As Mikhail Gorbachev announced the demise of the Soviet Union, Hikmet Çetin declared:

Turkey is no longer the peripheral country it used to be during the cold war. It has gained a more central position on the map. ...Indeed, in an area that extends from the Atlantic to the Chinese border, Turkey is at the focal point of the sensitive balances.

Çetin also made the astonishing statement that "If you look at world problems, you can see that none of them could be tackled without Turkey." State Minister Ikram Cayhun declared that Turkey's progress in the 1980s made it "one of the developed states of the world," which it plainly did not.

So far, this rhetoric about Pan-Turkic nationalism, a revived Ottoman sphere, and Turkey's importance has not caused any problems. Quite the contrary, realistic policies and sober actions have been the order of the day. Further, Prime Minister Çiller has been almost silent on these topics. There is no immediate danger that Turks, taking inflated statements by politicians to heart, will get carried away with a sense of their own power, leading to serious errors. But these statements sow seeds that, while not harmful in themselves, could unsettle Turkey in the future. Many problems surround Turks and involve them - Bosnia, Greece, Armenia and Azerbaijan, northern Iraq, Syria, Cyprus - so the stakes are very high. An unnamed Western diplomat in Ankara summed up this concern: "We're heading into uncharted waters. It's very difficult, very dangerous and alarming."

OTHER EFFECTS ON THE MIDDLE EAST

Turkey's connections to the Southern Tier are fairly obvious, having to do with the Turkic language, immigrants, and customs (such as a shared cuisine). Iran's connections are deeper but also more subtle, and so call for more explanation. The Arabs and Israel have also become involved, at least at the margins.

Iran and the Turko-Persian Tradition

History. Central Asia and the Transcaucasus have for a thousand years been included in the "Persianate zone," a large cultural area marked

by the use of the New Persian language as a medium of administration and literature, by the rise of Persianized Turks to administrative control, by a new political importance for the 'ulama [Islam's rabbis], and by the development of an ethnically composite Islamicate society.

The Southern Tier had for millennia participated integrally in the development of Iranian culture. The Shahnameh, Iran's national epic, takes place mostly on what later became Soviet territory; the region's cities have a larger presence in the classics of Persian poetry than do those of Iran proper. Bukhara and Marv are two of the oldest and most important cities of Iranian civilization. Samarkand boasts the Gur Emir, Tamerlane's tomb, as well as many other great Islamic structures. Tashkent hosts ancient schools. Medieval figures such as the philosophers Alfarabi and Avicenna, the geographer Albiruni, the poet Ali Sher Navai, and the astronomer Ulugh Beg all lived in what we term the Southern Tier.

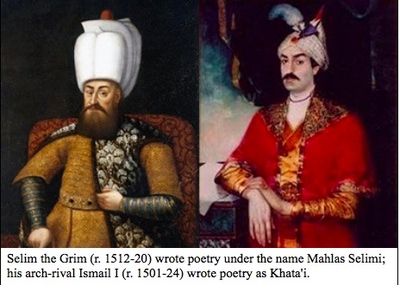

The Turko-Persian tradition developed in the Seljuk period (1040-1118) and reached its fullest florescence in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, when it prevailed in an area stretching from Anatolia to southern India, from Iraq to Sinkiang. The Ottoman, Safavid, Chagatay, and Mughal empires all subscribed to this civilization. Their prestige caused it to spread even beyond their boundaries, for example, to Hyderabad in southern India. The Turko-Persian tradition declined in the eighteenth century, when Europeans began to encroach and land trade declined. Still, Persian remained the language of culture in the Central Asian cities until the Russian Revolution.

Islam set the parameters in the Persianate zone, Turcophones ruled, and Iranians administered. As this implies, each of the three classical languages of Islam had a distinct function: Arabic belonged to religion; Turkish to the military; and Persian to administration, polite society, and the arts. In short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers. This mix led to unlikely juxtapositions: for example, shortly after 1500, the Iranian ruler Shah Isma'il wrote poetry in Azeri Turkic (under the pen name Khata'i) while his Ottoman counterpart in Istanbul wrote poetry in Persian.

Islam set the parameters in the Persianate zone, Turcophones ruled, and Iranians administered. As this implies, each of the three classical languages of Islam had a distinct function: Arabic belonged to religion; Turkish to the military; and Persian to administration, polite society, and the arts. In short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers. This mix led to unlikely juxtapositions: for example, shortly after 1500, the Iranian ruler Shah Isma'il wrote poetry in Azeri Turkic (under the pen name Khata'i) while his Ottoman counterpart in Istanbul wrote poetry in Persian.

The elites had much in common, from education to home life to styles of dress. But that was not all, as Robert L. Canfield of Washington University in St. Louis explains:

People on many levels of the society had similar notions about the ground-rules of cooperation and dispute, and in other ways shared a number of common institutions, arts, knowledge, customs, and rituals. These similarities of cultural style were perpetuated by poets, artists, architects, artisans, jurists, and scholars, who maintained relations among their peers in the far-flung cities of the Turko-Persian Islamicate ecumene, from Istanbul to Delhi.

Today. The Southern Tier's connections to Iran would seem to be moribund, overtaken by the delimitation of nation-states, Russian colonization, the Soviet experiment, and the Islamic Republic. But they are not: on both sides of the old Soviet border with Iran, the Turko-Persian tradition lives on.

On the northern side, the Turko-Persian tradition remained a source of pride and hope through seven decades of Soviet rule. In 1967 Olaf Caroe, the British administrator and author, explained that "it would be a profound mistake to imagine that the Sovietization of Central Asia and its populations has wiped clean the earlier drawings on the slate." In 1990, Graham Fuller reiterated the point: "the Persian legacy still runs deep in those republics, profoundly shaping their basic culture." Ex-Soviet Muslims have various connections to Iran. Tajiks share with it ethnic and linguistic bonds; Azeris share the Twelver Shi'i religious tradition; Armenians look to it for a potential balance to the Turcophones; and the whole region celebrates Nowruz (the Iranian New Year's festival in March ). Much else - music, cuisine, crafts - is also similar.

Today, dispirited by the devastation about them, many ex-Soviet Muslims see Persianate culture and Iran as sources of hope. Symbolic of this, the Tajiks have replaced a statue of Lenin with one of the poet Ferdousi, author of the Shahnameh. Turkmenistanis considered changing their currency unit to the dinar or tuman, though they eventually settled on the manat. Turkmenistan's President Saparmurad Niyazov told the foreign minister of Iran that he was "personally interested" in learning Persian and would facilitate its teaching in his country. On a visit to Iran, Kazakhstan's Minister of Culture Yerkegeliy Rahkmadiyev referred to the two countries' thousand-year relations and declared, "We consider Iran as our own home."

While today's republics have won a utilitarian acceptance, the old khanates of Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand live on in the imagination. The Great Ariana Society in Tajikistan advocates a Greater Khurasan, which would incorporate a Persian-speaking belt from the far end of Afghanistan to the Persian Gulf. Graham Fuller speculates that such a unit could become a counterpoise against a Turcophone belt to the north.

On the Iranian side, too, the Turko-Persian tradition survives. Government officials are generally cautious in their public statements, disclaiming interest in political influence, seeking only a softer kind. According to Foreign Minister 'Ali Akbar Velayati, "the export of revolution means the export of culture and ideas, no more." As a sign of the kind of influence Iranians hope to have, Velayati himself delivered a lecture at the Turkmen Academy of Sciences on the poet and thinker Mahdum Kuli. President Hashemi-Rafsanjani contented himself with bland statements. "The newly independent countries to the north are very dear to us," he declared in late 1992.

Still, indelicate expressions - betraying the Iranians' excitement - sometimes get articulated. Velayati spoke of Central Asia's "Iranian identity" and noted that it is impossible to look at the region "without making reference to Iranian culture and to the Iranian language." The religious leader of Isfahan, Ayatollah Taheri, held that "some of the newly independent republics of the former Soviet Union do not agree to the ignominious Turkmanchai Treaty between Iran and the former Soviet Union [actually Russia] and consider themselves part of Iran and regard the esteemed leader [Khamene'i] as their own leader."

An Iranian journalist explains this impulse: "In our heart of hearts, we know that Azerbaijan and Turkmenia [Central Asia] were once part of the Persian empire." Some Iranians explicitly say as much; Sarhadizadeh, a former minister of labor, predicted that independent Azerbaijan would eventually "become part of Iran." The prayer leader of Mashhad echoed, "The Treaty of Turkmanchay expired several years ago, and these countries are now parts of Iran."

Interestingly, Iran's political "moderates" articulate these dangerous dreams more than its "radicals." That's because the radicals have only Islamic aspirations, while the moderates have Persian nationalist ones as well. For the latter, Shahram Chubin notes, the new states "could in theory become a new constituency or audience, widening the strategic depth of the Islamic republic and deepening its base." Powerful elements within Iran, in short, appear to want to create a sphere of influence that includes Azerbaijan and Central Asia.

In asserting their claims, these Iranians dismiss Turkey's claimed connections to Central Asia and Azerbaijan. Iran's deputy foreign minister reacted with scorn when asked about possible rivalry between Turkey and Iran in the area: "What rivalry? Turks have nothing in the area but local idioms close to Turkish. History, civilization, culture, literature, science - everything is Iranian."

The Arabs and Israel

Saudi activities in the Southern Tier consist in large part of building mosques, distributing Qur'ans, finding local agents, subsidizing pilgrimages to Mecca, and establishing a range of Islamic institutions. Tajikistan had just sixteen working mosques in the mid-1980s; thanks to Saudi largesse, some five hundred mosques a year were built over the next four years. According to The Washington Post, Riyadh has spent over $1 billion just on Islamic centers and efforts to promulgate the Arabic language. The response was mixed. Kyrgyzstan declined an invitation to the Saudi-dominated Organization of the Islamic Conference in October 1991, but a year later signed an accord to accept aid and an Arab information-cultural center. Realizing the weakness of their position, the Saudis quickly deployed their resources best to block Iranian influence over the Southern Tier by supporting Turks. As Khalid Duran observes, "These days the Saudis appear pleased when the Turks defeat the Iranians, and it doesn't matter if the Turk is a Kemalist or a Wahhabi" - a secularist or a fundamentalist.

The Syrians joined the fray by establishing connections to Armenia. It helped that President Levon Ter-Petrossian was the son of a Communist Party leader in Syria, but a shared hostility to the Republic of Turkey provided the real basis of cooperation. Yerevan opened an embassy in Damascus during the depths of its siege in April 1993. In turn, Syria's President Hafiz al-Asad promised 7,000 tons of fuel oil gratis to the starving Armenians. In early 1993 Azerbaijan's President Elçibey announced that five hundred terrorists had arrived in Armenia from Lebanon, while his ambassador in Ankara asserted that Syrian citizens fought with Armenia against Azerbaijan. The Turks permitted a scheduled Aleppo-Yerevan flight until early April 1993, when Armenian aggression in Azerbaijan caused the Turks to cancel this and all other flights between the two countries. Accordingly, when the Armenian foreign minister visited Syria a few days later, he traveled via Paris.

Southern Tier independence has stirred much interest in Israel, including a hot debate whether it is a positive or negative development. Chief of Staff Ehud Barak expressed a pessimistic view about the emergence of the Southern Tier states: "new Muslim republics in Asia don't seem to me something that will add to our health, at least in the long term." When fundamentalist Muslim demonstrators took to the streets of Tajikistan in April 1992 carrying Khomeinist signs proclaiming "Death to Israel ," this worry seemed to be borne out.

But this agitation proved to be very much the exception. Most voices from the Southern Tier insisted that religious differences or the Arab-Israeli conflict not obstruct good relations with Israel. For the leaders, ties with Israel symbolized an anti-fundamentalist orientation. A pro-Israel outlook was understood to enhance one's standing in the West. Jewish immigrants from the Southern Tier were expected to invest in their countries of origin. For their part, Israelis responded with alacrity. In addition to the usual reasons for seeking good relations, they particularly welcomed warm ties with predominantly Muslim states; and they looked ahead to setting up networks for the day when the region's 200,000 Jews might need to leave in a hurry.