The United States faces a new adversary, the radical fundamentalist Shi'i Muslim. He first appeared with the rise to power of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1978 and has grown more dangerous in subsequent years. His ideology, tactics, and goals make this enemy dissimilar to any encountered in the past. The scope of the radical fundamentalist's ambition poses novel problems; and the intensity of his onslaught against the United States makes solutions urgent.

Attacks on Americans

Initially, problems caused by the radical fundamentalists were confined to Iran. These began during the revolt against the Shah of Iran in 1978, when they occasionally assaulted Americans. (Best known of their American victims were two employees of Ross Perot's Electronic Data Systems who were thrown in a Tehran jail without charges and eventually rescued by a private team hired by Perot.)

Although most Americans had left Iran by the time Khomeini took over, the few who remained faced increasingly unpleasant circumstances. In particular, the U.S. Embassy in Tehran became the symbol of fundamentalist hostility; seized briefly by Khomeini's followers in February 1979, it was then taken for a second time in November and held for 444 days.

The hostage problem received enormous attention in the United States, but Iran was quickly and gratefully forgotten the instant that specific issue was resolved. Bad memories, limited access, and a barrage of hostile propaganda caused Iran to disappear from the national consciousness. The reverse, however, did not take place; Iranians retained their obsession with the United States. The radical fundamentalist ruling Iran, it soon became apparent, saw the eviction of Americans from Iran as only a first step in a more extensive campaign.

Soon after it came to power, Khomeini's regime began fostering and aiding radical fundamentalist groups in other countries; these have since emerged as a force to be reckoned with in several parts of the Middle East. Foremost are Ad-Da'wa in Iraq, the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain, and several organizations in Lebanon, including Hizbullah ("The Party of God" in English), Islamic Amal, and Islamic Jihad. In addition to their efforts to win power for Shi'i fundamentalists, several of these groups have taken up arms against the United States.

Although Iranian-backed attacks on Americans have been attempted in many places, they have succeeded just in Lebanon, and for obvious reasons. Lebanon offered the radical fundamentalists, as it had the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) a decade earlier, the unique advantage of freedom from state control. Anarchic conditions in Lebanon made it an ideal base for Iranian terror against the United States. With enough determination, forceful groups could operate as quasi-sovereign bodies in Lebanon.

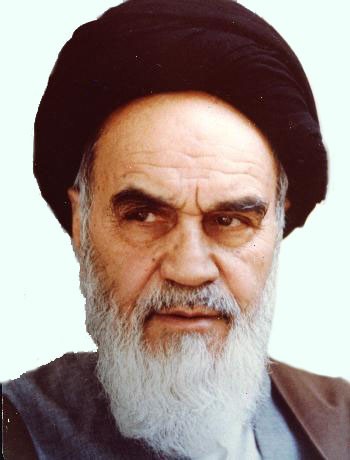

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini |

- 2 bombings of the U.S. embassy in Beirut on 18 April 1983 and 20 September 1984;

- bombing of the embassy in Kuwait, on 12 December 1983;

- a plot against the embassy in Rome just barely foiled in November 1984;

- destruction of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut on 23 October 1983, killing 241 soldiers;

- kidnapping of David S. Dodge, president of the American University of Beirut for one year (17 July 1982 - 21 July 1983);

- assassinated of another AUB president, Malcolm Kerr, on 18 January 1984;

- abduction of at least five Americans off the streets of Beirut between March 1984 and January 1985;

- torture and murder of two Americans on a hijacked plane in Tehran in early December 1984.

A fundamentalist group claimed responsibility for the violence in the aftermath of almost every incident. Fundamentalists also struck targets of other states, especially those of France and Israel.

These assaults raise three principal questions. What do the fundamentalists expect to achieve by attacking Americans? What is Iran's role in the violence? And what steps can the United States government take to protect its citizens?

The Assault on Western Civilization

Attacks on the United States are intended to achieve nothing less than the extirpation of Western civilization from the Middle East. This is so audacious, it may sound implausible; indeed, the alien nature and ambitious scope of fundamentalist aspirations does make it difficult for many Westerners to take them as seriously as they deserve. But few took Ayatollah Khomeini at his word when he declared his plans to build an Islamic society in Iran, and he did carry through. If nothing else, the radicals' savage record argues for very close attention to their plans.

Fundamentalists approach public life with two characteristic concerns. First, they draw strict dichotomies in every sphere of life, dividing everything into the Islamic and the non-Islamic, the Muslim and the non-Muslim. This applies, for example, to food, culture, individuals, and governments. Second, they painfully feel the weight of Muslim decline. Glories of the medieval period, real and imagined, are often conjured up and compared with the backwardness, poverty, and weakness of today. Confronted with this predicament, fundamentalists are obsessed with the challenge to make God's faithful once again great.

They advocate that Muslims seek solutions in Islam and believe Muslim supremacy will be regained only with strict adherence to Islamic doctrine and regulations. Fundamentalists ascribe the Muslims' tribulations in modern times to misguided efforts at emulating the West. They note that many Muslims began to adopt Western practices from about the year 1800, hoping to attain what the Europeans had by doing as they did. In the process, of course, these Muslims distanced themselves from Islam, a critical mistake from the fundamentalists' point of view.

But enshrining Islam as a guide to modern life entails complications. Although fundamentalists insist that they are only returning to old ways, the solutions they demand from Islam go far beyond the religion's traditional scope. In particular, they seek Islamic guidance concerning the distribution of economic and political power. Fundamentalists turn Islam into an ideology, a full-blown alternative to liberalism, communism, fascism, democracy, and other ideologies from the West.

America and West Europe, whose influences have had so wide and deep an impact in Muslim countries, are viewed by fundamentalists as the principal obstacle to the application of the Islamic ideology. Fundamentalists regard the ways of the West as seductive and evil, luring believers from the true religion, deceiving and debilitating them. To save Muslims, they strive to remove the temptation of Western civilization. Elimination of the Western, and especially the American, presence from Muslim lands, therefore, represents a fundamentalist priority.

America stands out due to its size, dynamism, and moral foreign policy; due to its unparalleled economic, military, and political power; and due to its cultural pre-eminence. America stands so often at the leading edge of civilization, the fundamentalists almost inevitably choose it as their premier target.

Although the powerful appeal of American culture disturbs all fundamentalists, few of them are in a position to combat it. Most devote the bulk of their attention to preaching in mosques and staying out of the authorities' way. Only in Iran, where radical fundamentalists have gained power, can the issue of America's cultural threat receive the requisite attention. And Iran's leaders do take this struggle very much to heart. Ashgar Musavi Khoeiny, leader of the 1979 attack on the U.S. embassy in Tehran, for example, recently defined the main objective of the Iranian revolution as the "rooting out" of American culture from Muslim countries.

Terror Against the United States

But how to do so? Diplomatic, economic, moral, and other methods of peaceful suasion cannot work, for Americans obviously will not readily pack up and leave the Middle East. Khomeini's followers therefore resort to coercion; and the coercive means most suitable for them is terrorism. Terror reduces differences in power between Iran and the United States, and enables Tehran to take steps not available to Washington. In the words of a Saudi prince: "These small countries know that only people who have stopped the American superpower have been terrorists. They stopped you in Vietnam. They stopped you in Iran. They are stopping you in Lebanon. That is why they attack you. It is the only way." The many deadly attacks on Americans since 1979 make it clear that Iranian leaders intend to make full use of this advantage.

A pattern emerges as anti-American incidents recur. Fundamentalist Muslims direct terror primarily against those Americans associated with major institutions. Note the affiliations of the five Americans plucked off the streets of Beirut and taken hostage in the year after March 1984: William Buckley, a political officer at the United States embassy; Jeremy Levin, a correspondent for the Cable News Network; Peter Kilburn, a librarian at the American University of Beirut; the Rev. Benjamin Weir, a Presbyterian minister; and the Rev. Lawrence M. Jenco, a Roman Catholic priest. Each of these men represents an institution deemed threatening by the Iranian rulers and their agents: the American government, media, schools, and churches.

Not surprisingly, the U.S. government looms as the largest enemy of the fundamentalists. Official American installations have therefore been the target of preference for fundamentalist attacks. The media are intensely resented for what is perceived as anti-Islamic bias; better that they leave the Muslim world and not have information to distort. Universities present special dangers by virtue of the profound influence they exert over young Muslims. As Ayatollah Khomeini explained, "We are not afraid of economic sanctions or military intervention. What we are afraid of is Western universities." Missionaries are seen as spearheading centuries-old Christian efforts to steal Muslims away from their faith.

Assuming that their hatred for the West is reciprocated, radical fundamentalists suspect that all Americans living in the Muslim world engage in espionage. Thus, Islamic Jihad accused the five American hostages in Lebanon of "subversive activities." "These people are using journalism, education and religion as a cover, and they are in fact agents of the CIA." The radicals believe that their efforts threaten the West as much as the West threatens them. They have as much difficulty imagining American indifference to them as Americans have imagining fundamentalist obsession toward themselves.

The fundamentalists do not hide their intentions to continue and even accelerate their aggression against Americans. In November 1984, a member of Islamic Jihad threatened to "blow up all American interests in Lebanon." The spokesman made clear who would be targeted: "We address this warning to every American individual residing in Lebanon." Two months later, this threat was renewed: "After the pledge we have made to the world that no Americans would remain on the soil of Lebanon and after the ultimatum we have served on American citizens to leave Beirut, our answer to the indifferent response was the kidnapping of Mr. Jenco.... All Americans should leave Lebanon." In reply, a spokesman for the Department of State declared that "the U.S. is not going to be forced out of Lebanon." Islamic Jihad then answered, the five American hostages "are now in our custody preliminary to trying them as spies.... [They] will get the punishment they deserve." Such trials may well be held.

Future attacks on Americans will probably be directed against all those institutions already hit as well as a significant addition-multinational corporations. American banks, oil producers, airlines, gasoline retailers, and the like are widespread in the Middle East, exposed, and controversial; this makes them an inevitable mark. Attacks on commercial organizations will be severely felt for they cannot absorb many blows. They will leave as soon as the expense and effort of coping with terrorism exceeds the benefits to be gained by staying.

Embassies, news bureaus, schools, and churches have no such clear measure; they will presumably remain longer in the Middle East. But they will stay only by becoming more discreet and by adding multiple layers of protection. Such steps work, to be sure, but unlisted numbers and barricades diminish the effectiveness of these institutions-exactly what the fundamentalists want.

Unless steps are soon taken, they will be in a position to force Americans to retreat from many parts of the Middle East. This would not only strengthen the forces of radical fundamentalism, but it would also create extraordinary opportunities for the Soviet Union. What could be more to Soviet advantage than for America's influence to dissipate in this critical region and for its institutions go into hiding?

Iranian Responsibility

Not every terrorist act against Americans can be directly or unequivocally connected to the Iranian government, but circumstantial evidence compellingly suggests that strong ties exist between Tehran and the radical fundamentalists.

Radical fundamentalist Muslims first arrived from Iran in the Baalbek region of Lebanon in December 1979. Although dispatched to fight Israel, their small numbers and poor training rendered them ineffective. A second contingent of Iranians then went to Lebanon in June 1982; rather than try to take on Israel, these soldiers took advantage of the turmoil following the Israeli invasion to organize and galvanize the Shi'is of Southern Lebanon. They formed alliances with Lebanese organizations such as Islamic Amal and eventually established an Islamic government in Baalbek along Iranian lines. More Iranians were sent to Baalbek; by the end of 1982 they numbered about 1,500. Money and arms provided by Iran brought in Lebanese; according to the Lebanese newspaper An-Nahar, one fundamentalist organization alone, Hizbullah, disposed of about 3,000 fighters in September 1983. Recent estimates put its numbers at about 5,000.

The Lebanese movement publicly proclaims that it is inspired by Khomeini. In the words of a young member of Hizbullah, "We are an Islamic revolution... Iran was a big influence on us." When Hizbullah's troops left Friday prayers in Baalbek during September 1983, Tehran television noted that "their procession was led by Muslim religious authorities who were carrying banners proclaiming the necessity to spread the Islamic revolution [of Iran] and fight against the enemies of Islam." More succinct is the graffito found on many walls of Beirut: "We are all Khomeini."

The Lebanese Shi'is frequently adopt the rhetoric and goals of the Iranian government. A member of Hizbullah was recently quoted as saying, "Our slogan is 'death to America in the Islamic world'." Another was even more ambitious: "The future is for the Muslims. The Soviet Union and the U.S. want to take over the earth. With Imam Khomeini, we can succeed to take these forces out, to destroy these forces."

The two sides agree on the value of terror against the United States. Husayn Musawi, the leader of Islamic Amal, called the 1983 attack on the Marine barracks "a good deed." For its part, the media in Tehran portrayed this attack as an act of "popular resistance." An Iranian editorialist wrote that "the American soldiers had died like Pharaohs under the rubble of their temple," and the Iranian government conspicuously avoided condemning this and other suicide attacks. In the Kuwaiti Airlines hijacking, collusion between the Iranian government and the terrorists appeared almost certain. With regard to this incident, the President of Iran, Sayyid 'Ali Khamene'i acknowledged that "the Islamic movement and the anti-Zionist and anti-U.S. stance of the Lebanese nation is supported by the Islamic Republic of Iran."

Control from Iran, though hard to trace, is unmistakable. Much of the movements' funding, arms, and organizational expertise comes from Iran. In the words of a Hizbullah leader in Lebanon: "Khomeini is our big chief. He gives the orders to our chiefs, who give them to us. We don't have a precise chief, but a committee."

Diplomatic Solutions

Fundamentalist terrorism represents a new challenge for Americans. Other enemies of the United States employ terror to change specific government politics; but the fundamentalists seek nothing less than the expulsion of Americans-private individuals and organizations as well as government officials-from the Middle East and the Muslim world. As Husayn Musawi explained, "we are not fighting so that the enemy recognizes us and offers us something. We are fighting to wipe out the enemy."

Precisely because fundamentalist Muslim goals are so extravagant, strategies against the Iranian campaign of terror are difficult to formulate. Appeasement, usually the wrong response anyway, is completely out of the question here. The United States government cannot abandon the Middle East, much less can it force American citizens to do so. Further, a great majority of Middle Eastern Muslims would not want Americans to depart.

Other than purely defensive measures or appeasement, what steps can the United States take to prevent further incidents? Two approaches offer possible answers: diplomacy and retaliation.

Diplomatic efforts directed toward Tehran or the fundamentalist groups in Lebanon are almost certainly futile, for neither will accept less than the ousting of Americans from the region. Instead, diplomacy has to concentrate on finding allies in the battle against the radical fundamentalists among those who fear their power. Many Frenchmen have been killed by them and their violence has spread to Kuwait and Italy; the Israelis, to their shock, find Shi'i groups in South Lebanon more ferocious than the PLO; other factions in Lebanon dread the prospect of increased Shi'i power; and Lebanese Shi'is who are not radical fundamentalists reject the aggressions of their coreligionists.

This list is formidably long, but one must doubt that any of the states would be willing to expend much treasure or blood in Lebanon; and the other Lebanese have shown that they can no longer contain the fundamentalists.

Only one country could and would intervene: Syria. Were the Syrian authorities inclined to do so, they could crack down on Lebanese fundamentalist power in a number of ways. The conduits that bring money, arms, and other forms of aid from Tehran could be cut. Other Lebanese factions could be assisted against the Shi'is. Or Syrian forces could be used to the same end.

But why should Hafiz al-Asad choose to interfere? For two reasons. Since the Lebanese civil war broke out in 1975, Syria's guiding concern has been to prevent any faction from controlling the country. When Maronites ruled in 1975, Damascus supported the rebel forces; as the rebels, including the PLO, threatened in 1976 to take over, it made an abrupt volteface and supported the Maronites. As the Maronites emerged with new strength in 1976, the Syrians again backed the rebels. One of the rebel factions, the Shi'is, now threaten to control most of Lebanon, and the Syrian leaders must surely be preparing to prevent them.

Shi'i control threatens in another way too. Led by the Muslim Brethren organization, fundamentalists in Syria constitute the most dangerous opposition to the Syrian government. So feared were the Brethren that the authorities made membership in the group a capital crime in July 1980. In December 1980, Syrian military forces attacked a Muslim Brethren camp at Ajloun in Jordan, bringing the two countries near war. Given this apprehension, Damascus must be extremely concerned that fundamentalists in Lebanon might funnel aid to their Sunni colleagues in Syria. The January 1985 declaration of an amnesty for members of the Muslim Brethren may indicate that the government, fearing a coalition of fundamentalists, seeks to appease its opposition. Should this be the case, Damascus would have clear reason to turn against the Shi'i fundamentalists in Lebanon.

An American deal with President Hafiz al-Asad would not be easy to arrange, if for no other reason than that their policies have for years run in opposite directions. Nonetheless, these two governments-as well as other states and most Lebanese citizens-many find they have a common interest in suppressing the radical Shi'is of Lebanon.

The United States might encourage the Syrian authorities in this direction, perhaps by indicating a willingness to deal with Damascus on issues outstanding. Inquiry into Syrian desires could produce areas for cooperation. Or the United States could show flexibility about revising the Reagan Initiative to include Syria or more actively mediating between Syria and Israel.

Retaliation

Diplomatic efforts should be tried but not counted on. They cannot substitute for a willingness to oppose force with force. In contemplating the use of violence, the American objective must be to find steps that discourage further terrorist incidents. As ever, many constraints tie American hands. To begin with, three considerations rule out a direct strike against Iran.

First, the United Stats cannot take actions that risk bringing the Soviet Union into Iran, for this would facilitate Soviet control of the Persian Gulf and render that region's oil flow even more vulnerable than it already is. Restrictions on the free flow of oil could have the gravest implications for the United States and its allies, possibly leading to the neutralization of Japan and the breakup of NATO. Keeping the Soviet Union out of Iran and the Persian Gulf must have highest priority in United States policy. This being the case, Washington cannot take chances with measures that might lead to Iran's territorial disintegration. However obnoxious the ayatollah's policies, American interests require that the government in Tehran retain firm control over the entire country. All actors-the Iraqi military provincial rebels, exile opposition groups-who reduce Tehran's authority contradict those essential interests. Frustrating as it is, the United States must not harm the Khomeini government's grasp of power.

Second, Iranian military targets are off-bounds. Attacking them would mean in effect joining Iraq's war effort against Iran, entailing many undesirable consequences. This would align Washington with the aggressor in the Iraq-Iran war and tie it closely to one of the most repressive regimes in the Middle East; it would impel Iran further into the Soviet camp; and, far from reducing acts of terror against American citizens, cooperation with Saddam Husayn would increase them. For these reasons, all Iranian targets with military value, regardless how insignificant or remote, and all important economic facilities, such as the oil-exporting port of Kharg Island, must be inviolate.

Third, the United States is restricted by its own standards of morality; it cannot imitate the Iranians and strike out blindly against civilians. The United States must uphold certain standards of behavior, even when its enemies do not.

These three restrictions effectively exclude American actions against Iran. Striking some targets could endanger the stability of the government; others would make the United States the ally of Iraq; and still others would contravene American ethical standards.

If Iran itself escapes retaliation, its agents abroad-and especially those in Lebanon-need not. Striking the radical fundamentalists in Baalbek avoids the risks associated with striking Iran itself. It would not destabilize the government in Tehran, and the Iranians in Lebanon are not involved in the war with Iraq. But they are actively engaged in terror.

The United States government has often threatened retaliation against the radical fundamentalists, but not yet carried through. Philip Taubman explained in The New York Times why nothing happened after the September 1984 bombing in Beirut:

Officials said today [4 October] that President Reagan and his senior aides had not authorized a retaliatory strike against the Party of God [Hizbullah] both for practical and policy reasons.

Military and intelligence aides, according to the officials, have advised the White House that because the group's leaders and followers do not ever assemble in one place, an air raid would be ineffective and would risk killing innocent civilians.

The White House was told it would also be difficult to introduce American forces covertly into the Bekaa to carry out a commando raid.

Equally important, the officials said, is a widespread belief among Mr. Reagan's aides that a retaliatory strike against the Party of God or Iran would only produce an escalation in terrorist attacks against the United States.

These reasons for inactivity no longer suffice. If the United States lacks the capabilities for air strikes or commando raids, these must be developed immediately. The enemy's practice of surrounding himself with innocents cannot be allowed to inhibit all American use of force. And the fear of provoking more terrorist attacks carries no weight in the aftermath of the Tehran hijacking outrage. As Secretary of State George P. Shultz has noted, "a great power... must bear responsibility for the consequences of its inaction as well as for the consequences of its action."

The only serious hesitation with regard to attacking fundamentalist installations in Lebanon has to do with efficacy. Would exacting a heavy price for atrocities against Americans provide a disincentive for the enemy? Or are the means and the will there to rebuild the facilities?

This question is difficult to answer in the abstract, for the adversary is elusive and his means uncertain. Instead, the reverse point should be strongly emphasized: the absence of punishment encourages fundamentalist to challenge the United States. How can they but despise a power that can be hit time after time without fear of retribution, that does not protect its citizens, that does not go beyond verbal indignation?

Time has come for the United States to retaliate. Punishment of the terrorists who are most implicated and most vulnerable-those in the Baalbek region-presents the best opportunity to protect Americans and their interests in the Middle East. If the Syrian government can be induced to cooperate, so much the better; but if this fails, the United States must gird to undertake a costly and unpleasant conflict.

To the editor:

Americans living in Lebanon are surprised and disturbed by the article of Daniel Pipes (Vol. IV, No. 1). The article is misleading and harmful to American interests, not only in various details but also in its general tone.

1. On page 4 he mentions several terrorist attacks for which he accuses Shi'i groups without any solid evidence. An anonymous telephone call claiming responsibility on behalf of a certain group may be authentic, or it may be that the name of the group was invented to conceal the true identity of the terrorists. (For example, in 1954 Israel attacked U.S. interests in Cairo and Alexandria, hoping that America would blame Egypt). In particular, the murder of Malcolm Kerr was not claimed by any group, and his death was deeply mourned by Shi'i students who considered him their friend. Moreover, it is generally accepted in Beirut, as well as by William Quandt, who is at least as qualified as the author, that the crime was committed by extremists at the opposite end of the political and religious spectrum from the fundamentalists.

2. On pages 4-5 Pipes attributes America's vulnerability to its "moral foreign policy" and "cultural pre-eminence." A foreign policy which has long condoned and even supported suppression of human rights in several parts of the world can hardly be called moral. In particular, U.S. backing of the Shah against the people of Iran and of Israel's brutal treatment of Palestinians and Lebanese has unleashed a reaction against amoral policies. As for American culture, most of the world sees only its materialistic side. For example, tobacco companies required by law to warn American customers boldly export cigarettes to other countries without including the Surgeon General's warning. And anyone who has seen commercials on Lebanese television knows that the tobacco industry clearly portrays its deadly product as an essential ingredient of American culture.

3. On pages 5-6 Pipes draws attention to the fact that the Americans abducted in Beirut represent the U.S. government, media, schools, and churches. Since any American in Lebanon nowadays would almost certainly be in one of these categories, this fact is of little significance to the author's thesis. For example, an American businessman or laborer or entertainer would be virtually impossible to kidnap here.

4. Worst of all, the author states that the possible loss of innocent lives should not deter the U.S. from retaliating against terrorists. But this mentality is indistinguishable from that of the terrorists, who believe that their cause is noble enough to justify human sacrifice. However, fanaticism is not stopped by physical force. The blood of the martyrs will win new converts, and the situation will only worsen.

The correct solution is to find ways of making fanaticism and terrorism unnecessary. For example, if the U.S. had stood against the Israeli war on Lebanon instead of cynically trying to reap some political spoils, it would have made many more friends than it lost. If it had insisted on an unconditional Israeli withdrawal instead of forcing the "agreement" of May 17, 1983, the danger to U.S. Marines would have been considerably reduced, and the Lebanese government would have been strengthened. If it would take a moral stand in the U.N. Security Council instead of casting mindless vetoes against Lebanon, its prestige would be greatly enhanced. In this connection, some Americans in Beirut publicly stated in March that they stood with the oppressed Lebanese people rather than with their own government. Precisely because their government had no moral foreign policy which would have protected human rights as well as the lives of its Marines and other citizens, they felt that they had to lead the way.

Peter Yff

American University of Beirut

Beirut, Lebanon

Daniel Pipes replies:

I shall take up Peter Yff's points in order.

First, do I accuse the Shi'i groups of terrorism "without any solid evidence"? The leaders of the major Shi'i fundamentalist groups (such as Mussavi and Fadl Allah) condone terrorism, even while distancing themselves from responsibility. So too does the government in Iran. The police in several countries, such as Spain and Denmark, accept Shi'i claims for responsibility for terrorism in their territory. The pattern of events confirms this: until a few years ago, when the radicals came to power in Iran, Americans were not murdered and abducted as they are now. Finally, there is a question of purpose: I tried to explain in my article why fundamentalist Muslims would want to kill the president of A.U.B. and abduct its U.S. faculty; the burden rests on Mr. Yff to demonstrate why other groups would wish to do so.

Second, I call American foreign policy "moral" because I see it as the single greatest force for democracy and freedom. Support for the shah of Iran and Israel are entirely consistent with this goal. For proof, compare the situation under the shah and under Khomeini; compare the situation in Israel and in any of its neighbors.

Of course, the materialism of American culture has vast influence. My article devotes some space to this, and specifically mentions "machines, clothing, foods, and furnishings." But there is more, as someone working at the American University of Beirut should know well; there is the attraction of American culture. On the matter of American tobacco companies and the warnings on cigarette boxes: Not only is this irrelevant to American standing in the world, but it would defy human nature for the same companies that strenuously object to the Surgeon General's warning in the U.S. voluntarily to include it in Lebanon.

Third, Mr. Yff claims that almost all Americans in Lebanon today are affiliated to the government, media, schools, or churches. He is contradicted by The New York Times. In an article published on June 16, 1985, Ihsan A. Hijazi writes that there are about 1,000 Americans in Lebanon and about 60 in West Beirut. He estimates that 30 Americans are at A.U.B., 30 with the U.S. embassy, and 10 engaged in relief and charitable work. The vast majority of Americans in Lebanon do not have institutional affiliations and I argue that they are left alone precisely for this reason.

Fourth, the notion that retaliation against terrorism makes the U.S. "indistinguishable from ... the terrorists" implies that the only acceptable defense is acquiescence. Mr. Yff would cede all use of force to the enemy and rely on its good will. His knowledge of history is weak; fanaticism has often been stopped by force. How does he think the Baader Meinhoff gang and the Red Brigades were broken?

Mr Yff's concluding remarks on the proper direction of U.S. policy in the Middle East are as ill-informed as the rest of his diatribe. But one thing he mentions is most revealing: the

statement in March 1985 by Americans living in Lebanon that they stood with the "oppressed Lebanese" rather than with their own government. This is a clear instance of the "Stockholm Syndrome," the tendency of hostages to advocate the aims of their captors. They

desperately want their own government to accept the captors' demands, for the obvious

reasons that acceptance will help them survive. Similarly, the Americans in Lebanon—

including Mr. Yff if he is American or could be mistaken for one—advocate radical anti‑

American policies for their own safety. Self-preservation, not the best interests of the United States or Lebanon, explains the distorted views Mr. Yff promotes.