News reports about the Michigan Militia and other extreme-right groups belonging to the so-called Patriot Movement, allegedly connected to the bombing in Oklahoma City, portray them as a phenomenon of the past few years. A New York Times story, for instance, traces the groups back no further than 1983.

But their political views and psychology are part of a much longer history. The Patriot groups primarily see the world in terms of conspiracy theories: the Federal government is conspiring to deny Americans their constitutional freedoms; Zionists are conspiring to control the government, as are foreign states. Typical of this outlook, right-wing extremists claim that the Federal government staged the Oklahoma City blast, as a way of winning sympathy and justifying a crackdown on Patriot groups.

This obsession with conspiracies derives from a very old legacy of European and American thinking. Only by seeing the groups in this light can we understand who they are, what menace they pose, and how to deal with them.

The West hosts two main conspiracy theories: one, mainly right-wing, fears that Jews seek world hegemony; the other, mainly left-wing, worries about secret societies such as the Jesuits and the Freemasons. Each of these phobias, in its furthest, most murky reaches, goes back to the Crusades, the Christian wars between 1096 and 1291 that sought to conquer the Holy Land.

The Crusades vastly increased the incidence of anti-Semitism in Christian life; about this time, enduring defamations against Jews - such as their ritual murder of Christian children and desecration of Christian cult objects - took hold. Anti-Semites eventually developed a unified conspiracy theory that began with Herod and included everyone from medieval rabbis to Karl Marx. They came to believe that Jews seek control of the world.

At the same time, the Crusaders' eventual failure to hold on to the Holy Land aroused conspiracy theories about those secretive Christian military orders, and most notably the Knights Templar. Many suspected the Templars of treachery; and in later centuries this fear of betrayal extended to such diverse groups as the Philosophes, international financiers, and the Council on Foreign Relations.

The two conspiratorial traditions crystallized into their current form in Russia during the 1890s. Two publications had a key role: on the right, the tsar's secret police forged The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the standard text of anti-Semitism; on the left, Lenin produced his main theoretical writings on imperialism. These writings had a very substantial role in motivating Hitler and Stalin, respectively, both of whom were obsessed with plots; conspiracy theories thereby substantially contributed to the single most awful event in human history, the Second World War.

But conspiracy theories are not just a European phenomenon. Even in the United States, this most remote and favored of countries, the list of suspected conspirators is long. As the historian David Brion Davis explains, Americans have been "curiously obsessed" with conspiratorial fears "of the French Illuminati, of Federalist oligarchs, of Freemasons, of the money power, of the Catholic Church, of the Slave Power, of foreign anarchists, of Wall Street bankers, of Bolsheviks, of internationalist Jews, of Fascists, of Communists, and of Black Power."

These perceived threats inspired a host of conspiracy-mad institutions in the nineteenth century - the Antimasonic Party, the Know-Nothing Party, and the Ku Klux Klan, among others; the Michigan Militia's roots go back to those organizations. Fear of Communism spawned McCarthyism; the John Birch Society then isolated and institutionalized the most paranoid strain of McCarthyism; in one memorable campaign, it portrayed the adding of fluoride to drinking water, intended to prevent tooth decay, as a Communist conspiracy.

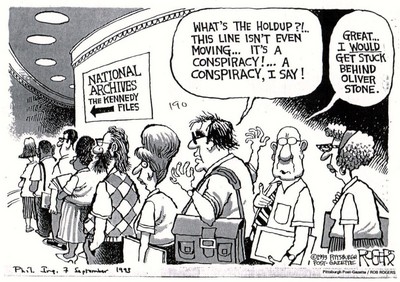

The assassination of John F. Kennedy in November 1963 shocked Americans, leaving many unable to come to terms with an event so senseless, and especially with the notion that a single gunman could so easily rupture the state. This disbelief opened the way for a multitude of conspiratorial explanations attempting to fit Kennedy's death into a larger scheme, thereby rendering it more acceptable. Time has not closed this wound. Opinion polls show that during the 1960s some two-thirds of Americans suspected a conspiracy; in 1992, partially due to the controversy surrounding Oliver Stone's JFK, a conspiracy-saturated film about the assassination, polls showed 77 percent of the American population believing Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone; and fully 75 percent believed in an official cover-up of the case.

Oliver Stone's conspiracism makes him the butt of jokes. |

Today, Americans may be more inundated with conspiracy theories than at any time since the heyday of Joseph McCarthy forty years ago. Suspicions circulate that two presidents out of the last seven (Johnson and Reagan) reached office through plots most foul. Susan Faludi's feminist best seller, Backlash, holds that women are the victims of a massive conspiracy perpetrated by the government, lawyers, the media, fashion designers, and Hollywood. A disproportionate incidence of drugs and AIDS among American Blacks prompts a widespread perception of conspiracy; survey data indicates that 60 percent of Blacks believe that the U.S. government deliberately spreads drugs in their community, while 29 percent believe the same in the case of AIDS. In brief, American culture is permeated with conspiracy theories.

Widespread as they are, conspiratorial ideas they have little operational importance these days. After long centuries of increasing importance, culminating in World War II, the West has in fact mostly shaken off the curse of conspiracism. Thanks in large part to Hitler and Stalin, who showed the grotesque price of conspiracy theories run rampant, the long Western fascination with conspiracy theories has dimmed. Voters and politicians in democratic countries no longer act on the basis conspiratorial beliefs; the core is solid. With the exception of Russia, these ideas very rarely drive government policy.

Instead, conspiracy theories have come to fill two roles in the United States. They serve as a kind of political pornography, titillating but without consequence. We enjoy feature films about conspiratorial themes (such as The Manchurian Candidate, Three Days of the Condor, and Wrapped in the Flag) and we unendingly buy books on the subject (in February 1992, five books on the Kennedy assassination made the best-seller lists); but these have almost no operational importance. Second, conspiracy theories serve as a refuge for the disaffected and the disturbed. For those who hate the existing order, at the left or right fringe, conspiracy theories offer a world view. Yesteryear's commonsense has turned into pathology.

This history has a positive and a negative implication. On the plus side, it suggests that large numbers of Americans will not adopt the evil ideas of the far right. On the minus side, the warped ideas of the Patriot Movement cannot be dismissed as the ravings of crazed minds; rather, they must be understood as the head of a beast with a nine-hundred-year long tail. Fortunately, its fangs have lately been filed down. But it deserves the serious treatment due a force that has wrecked terrible destruction over the centuries. Accordingly, right-wing extremists need to be battled not just in terms of law enforcement, but also on the level of ideas.

This history has a positive and a negative implication. On the plus side, it suggests that large numbers of Americans will not adopt the evil ideas of the far right. On the minus side, the warped ideas of the Patriot Movement cannot be dismissed as the ravings of crazed minds; rather, they must be understood as the head of a beast with a nine-hundred-year long tail. Fortunately, its fangs have lately been filed down. But it deserves the serious treatment due a force that has wrecked terrible destruction over the centuries. Accordingly, right-wing extremists need to be battled not just in terms of law enforcement, but also on the level of ideas.

Mr. Pipes is editor of the Middle East Quarterly and a senior lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania's Fels Center.