As the title of this study suggests, Allan and Helen Cutler believe that the tendency of medieval Christians to see the Jew as an ally of the Muslim was the decisive factor in the development of anti-Semitism. In making their case, the Cutlers challenge conventional wisdom, which holds that anti-Semitism originated in the charge of deicide (that Jews killed Jesus) and the Jews' anomalous socio-economic status in Europe. Although the Cutlers' study is poorly written and far too lengthy, it offers an intriguing and ultimately convincing argument.

The logic of their case can be reduced to a syllogism: (1) Medieval Christians feared and hated Muslims. (2) Medieval Christians saw Jews as the allies of Muslims. (3) Therefore, medieval Christians feared and hated Jews.

On the first point, the Cutlers are correct to note the presence of a pervasive fear of Muslims among medieval Christians. That fear began with the emergence of Islam and lasted until the 19th century. In 634, just two years after Muhammad the Prophet's death, for example, the patriarch of Jerusalem referred to the Muslims as "the slime of the godless Saracens [which] threatens slaughter and destruction." This early view was later echoed many times over; for centuries, the role of arch-enemy, in myth and literature, was filled by Muslims.

On the first point, the Cutlers are correct to note the presence of a pervasive fear of Muslims among medieval Christians. That fear began with the emergence of Islam and lasted until the 19th century. In 634, just two years after Muhammad the Prophet's death, for example, the patriarch of Jerusalem referred to the Muslims as "the slime of the godless Saracens [which] threatens slaughter and destruction." This early view was later echoed many times over; for centuries, the role of arch-enemy, in myth and literature, was filled by Muslims.

This is understandable, for Muslims, who inhabited a belt of territories extending from Morocco to Egypt to Turkey to Siberia, physically surrounded medieval Christendom. Muslims were also the most constant enemy: with only one exception (the Mongols), every serious military threat against Christian Europe after the 10th century was launched by them. The Muslim danger continued to preoccupy the Christians of Europe for more than a millennium, until after the second siege of Vienna in 1683.

Muslims also differed from the other invaders - Germans, Bulgars, and Hungarians - in presenting a religious and cultural danger as well as a military one. Hungarians would eventually accept European culture and convert to Christianity, but Muslims brought with them a rival civilization which not only withstood Christianity but even seduced Christians from their faith. For all these reasons, Muslims were the outstanding enemy of Christendom.

Second - and this is the heart of the Cutlers' study - Jews were seen as close associates of Muslims. There was some justice to this view: the Hebrew language shares much with Arabic, and Judaism shares much with Islam; on the most abstract level, both are religions of law, while Christianity is a religion of faith. More specifically, they share many features such as circumcision, dietary regulations, and similar sexual codes. Further, because the Muslims were preeminent in the medieval centuries, "Jews themselves associated Jew with Muslim." When this became known among the Christians, it much harmed the Jews' position. Most damaging of all, Jews on occasion helped Muslim troops against Christians (as in the initial Arab conquest of Spain) and some Jews held prominent positions in Muslim governments at war with the Christians. Even when they did not actually take part in the fighting, "Jews usually rejoiced when Christian territory fell into Islamic hands."

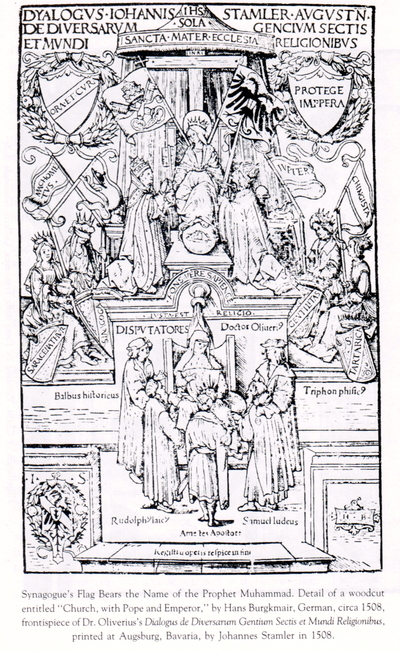

The Cutlers marshall a variety of textual and pictoral proof to make their case that medieval Christians saw a deep connection between Jew and Muslim. To take one of each: An influential twelfth-century Christian text includes the bizarre statement that "A Jew is not a Jew until he converts to Islam." The woodcut in a book of religious disputation published in 1508 pictures a Jewish and a Muslim figure: while the Jewish figure carries a banner with the name "Machometus" (Muhammad), the Muslim's banner depicts a Jew's hat. The Cutlers conclude:

The Cutlers marshall a variety of textual and pictoral proof to make their case that medieval Christians saw a deep connection between Jew and Muslim. To take one of each: An influential twelfth-century Christian text includes the bizarre statement that "A Jew is not a Jew until he converts to Islam." The woodcut in a book of religious disputation published in 1508 pictures a Jewish and a Muslim figure: while the Jewish figure carries a banner with the name "Machometus" (Muhammad), the Muslim's banner depicts a Jew's hat. The Cutlers conclude:

Since the rise of Islam, the primary (though by no means the only) factors in the history of anti-Semitism have been the following: the association of Jew with Muslim, the longstanding European tendency to equate the Jew, of Middle Eastern origin, with the Muslim, also of Middle Eastern origin; the intensely held Christian feeling that the Jew was an ally of, and in league with, his ethnoreligious cousin the Muslim against the West; the deep-seated Christian apprehension that the Jew, the internal Semitic alien, was working hand in hand with the Muslim, the external Semitic enemy, to bring about the eventual destruction of Indo-European Christendom.

Third, Christian fear of Muslims affected the view of Jews. In order to prove this thesis, the Cutlers must show that Christian anti-Semitism varied in response to Christian-Muslim relations. The status of Jews had to decline as Christian animosity toward Muslims increased; conversely, Jews had to be better off when wars against Muslims ceased. The authors do establish this point in a broad-brush sort of way, more by assertion than through a close look at the record. They argue that far fewer anti-Semitic outbreaks occurred in 700-1000, when Muslims were still a distant concern, than in 1000-1300, when they had become the victims of intense hostility. The Cutlers date the transition to about 1010, when rumors spread through France that the Jews had helped the Fatimid rulers of Egypt destroy the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. In retaliation, the Jews of Orleans were made to pay with their lives.

When viewed in the context of the age, the Muslim role in medieval anti-Semitism is not surprising, for Muslims had a profound impact on diverse aspects of medieval European civilization. Indeed, little took place in Christendom between the eighth and fifteenth centuries that was not influenced by Muslims. Prominent consequences include: Muslim victories using stirrups on horses compelled the Christians to imitate them and develop a social order which placed great emphasis on fighting horseman; in short, responding to the Muslim menace led to a reordering of European society along feudal lines. Muslim domination of the Mediterranean cut southern Europe from its traditional trading partners, inducing increased cultivation of northern Europe. Muslim intellectuals of Spain made Greek philosophy available, and in so doing contributed importantly to the Renaissance. Modern European imperialism originated in the Crusades, while Portuguese and Spanish naval discoveries were stimulated by the desire to circumvent the Muslims. Ottoman threats diverted the Catholic states and inadvertently facilitated the rise of Protestantism.

Muslims also affected smaller developments: the Mafia began as an anti-Muslim league, the Vatican was built to withstand Muslim attacks, and the Acropolis was ruined in the course of its use as an arsenal by Ottoman forces. Muslim influence pervaded the diet, clothing, and art of many Christian cultures.

This list could be extended much further; the key point is that Muslims touched on myriad aspects of Christian civilization of Europe. As the historian R. W. Southern has observed, "the existence of Islam [was] the most far-reaching problem in medieval Christendom. It was a problem at every level of existence." In this light, it is hardly surprising that the Muslims also affected the way Christians viewed Jews.

The authors strongly believe that medieval Christian perceptions remain a force today, that the notion of Jewish-Muslim alliance still fuels anti-Semitism. They even go so far as to argue that "Israeli antagonism toward Arabs may in part be affected by a Jewish desire (perhaps more subconscious than conscious) to disprove the historic Christian belief that the Jews are in league with the Muslims against the West." Christian anti-Semitism will endure so long as Christian anti-Muslimism remains potent. To combat anti-Semitism, the Cutlers therefore propose that "American and world Jewry should be ready and willing to put much more of its community-relations time, money, energy, and imagination into urging Christians and Muslims to enter into genuine dialogue and reconciliation."

This is a radical new approach; does it hold? In my view, the Cutlers' analysis of the medieval situation makes great sense; indeed, it adds a whole new dimension to our comprehension of the way Christian-Jewish relations developed. But I am very skeptical about the applicability of their insight to current circumstances. The reason is obvious: since World War I, conflict, not alliance, has dominated relations between Muslims and Jews. Indeed, the Arab-Israeli dispute has so overwhelmed earlier bonds between Muslims and Jews that the latter have virtually disappeared from view in the West. This change means that the old association of Muslims and Jews no longer holds.

Take the case of the Arabs' success in raising the price of oil in the 1970s. During the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, the Arabs emphasized their use of oil as a weapon against Israel. Each side then tried very hard to put the onus of blame for the price increases on the other. Under these conditions, it hardly seems likely that the Christian West would see Muslims and Jews as allies. To the contrary, the two parties have acquired a reputation of being even more hostile enemies than they in fact are. Only scholars recall the ties they had in centuries past.

Further, in a terrible twist of fate, Muslims have themselves become the leading international patrons of a Christian-style anti-Semitism in recent years. To take just one example among many, the defense minister of Syria, Mustafa Tallas, has recently published a book titled The Matzah of Zion in which he dredges out the classic accusation of blood libel. Tallas has adopted a position with which no prominent figure in the Christian West would still identify himself. The notion of Muslim-Jewish alliance in the face of such Muslim anti-Semitism is preposterous.

This is not to say, however, that the Cutler's thesis has no contemporary importance, for it does. To the extent that anti-Semitism results from Muslim-Jewish relations, it is transient and therefore malleable. The less critical the charge of deicide proves to be, the easier Christian-Jewish reconciliation becomes. If deicide is in fact not the historic core of the Christian persecution of Jews, anti-Semitism looks somewhat less permanent.

The Jew As Ally of the Muslim is a peculiar book. The second chapter is an arcane page-by-page commentary on another recent scholarly book. The final chapter suggests that the Pope should "transform his office and mission from a more narrowly Christian into a broadly Abrahamic one ... to create a new spiritual and institutional unity between Jews, Christians, and Muslims." But these shortcomings are more than made up for by the fact the Cutlers have an important new idea, one now available for others to build upon.

Jan. 1 2023 update: And now, someone has built on that premise. David M. Freidenreich, Pulver Family Professor of Jewish Studies at Colby College, has written Jewish Muslims: How Christians Imagined Islam as the Enemy. He explains his outlook compared to that of the Cutlers:

Jan. 1 2023 update: And now, someone has built on that premise. David M. Freidenreich, Pulver Family Professor of Jewish Studies at Colby College, has written Jewish Muslims: How Christians Imagined Islam as the Enemy. He explains his outlook compared to that of the Cutlers:

The argument of this chapter inverts that of Cutler and Cutler, Jew as Ally of the Muslim. As reviewers of that book uniformly observed, Allan and Helen Cutler failed to support their thesis that "anti-Muslimism" was the driving force behind Christian hatred of Jews. These authors did, however, provide an invaluable service by drawing scholarly attention to the relationship between Jews and Muslims in medieval Christian thought and to many of the primary sources that associate these groups with one another. Chapters 9-11 of the present book offer fresh analyses of these sources, among others.