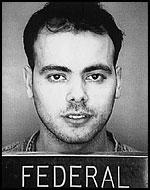

Mohamad Youssef Hammoud, an 18-year-old Shiite Muslim from Lebanon, arrived at New York's Kennedy Airport on June 6, 1992. He had come, accompanied by two close male relatives, from Caracas, Venezuela, where each of them had plunked down $200 for a counterfeit U.S. visa. American border guards caught the fraud, and the trio did not exactly begin their American careers with distinction; but they did begin them in character - with a crime. The U.S. government also responded in character, just as it would many times over the next eight years: It allowed them into the country.

Mohamad Youssef Hammoud |

The resourceful Hammoud then went underground. In May 1997, he married a second American, Jessica Wedel. In September 1997, while still married to Wedel, he took a third wife, Angela Tsioumas. (That she was already married to another man perhaps evened the score.) The INS, not too adept at record-keeping, mislaid its file on Hammoud's earlier marriage fraud and never noticed that both of the nuptial pair were married to others; so, on the basis of Hammoud's marriage to Tsioumas, the agency granted him conditional residency in July 1998. Only in October 1998 did Hammoud get around to divorcing Wedel.

To make matters even more interesting, the Hammoud-Tsioumas bond turns out to have been a complete fiction, just a way for him to acquire citizenship and for her to earn a few thousand dollars. Hammoud appears to have (truly) married a woman in Lebanon in 1999; Tsioumas has bragged that, as soon as Hammoud no longer needs her, she will marry other would-be Americans "for the right price."

One might imagine that Hammoud's desperate efforts to remain in the U.S. signaled his deep affection for the land of the free; or, at any rate, his longing to walk our streets paved with gold. One would be wrong. Like so many other Shiites from the shantytowns south of Beirut, this young man has adopted the Ayatollah Khomeini's brand of extremist Islam and virulent anti-Americanism. As a member of Hezbollah, the main Islamist terrorist and political organization of Lebanon, Hammoud came here not as an immigrant, to become American - but as a missionary, to bring Hezbollah's message into enemy territory.

Information about Hammoud is available in a powerful and detailed 85-page federal affidavit filed in late July in the U.S. District Court in Charlotte, North Carolina, based on the reports of six cooperating witnesses and five secret informants, physical surveillance, financial records, and much else. Hammoud, it seems, received military training in Hezbollah camps in Lebanon and boasts of being "well-connected" to Hezbollah leaders. One informant calls Hammoud "100 percent Hezbollah." Another thinks him dangerous because he "would likely assist in carrying out any action against United States interests" if Hezbollah asked him to. A third says Hammoud "would not hesitate" to commit a terrorist act in the United States for Hezbollah.

He's hardly the first of this type, nor the most famous (that distinction probably belongs to New York's blind sheikh). In a bitter and ironic development little noted by Americans, many recent immigrants arrive, as Martin Peretz puts it, "not with the immigrant's psychological one-way ticket, not with the immigrant's love for America, but with a peculiar immigrant's hatred of America." Islamists like Hammoud are perhaps the most significant of this breed, intensely hating the U.S. and all it represents, but also savoring the country's freedom of expression and of movement, its rule of law, its open institutions, its fine communications and transportation, and its superpower status. They also appreciate its affluence. As Iran, Saudi Arabia, Libya, and the other once-rich Middle East states curtail spending, Islamist groups like Hezbollah increasingly seek funding from coreligionists in the West.

Hammoud settled in Charlotte, and was busy on behalf of Hezbollah from the moment he arrived there. He organized his two brothers and three cousins, plus other Shiites from his old neighborhood in Lebanon, into what one informant terms "an active group" of Hezbollah members. They arranged nocturnal meetings in one another's houses several times a week and engaged in morale-boosting activities. They sang rousing Hezbollah songs (downloaded by Hammoud from the Internet), heard inspiring speeches of Khomeini and Hezbollah's leader, watched videotapes of Hezbollah victories over Israel, and discussed Hezbollah "activities and operations." One person who attended these meetings - the most recent of which took place on July 13, 2000 - calls their atmosphere "extremely anti-United States."

Having heated their emotions, Hammoud solicited donations for Hezbollah from his group and worked with them on a simple but audacious fundraising scheme for Hezbollah. It happened that these Muslims lived in North Carolina, home to the American tobacco industry and a state whose government adds a tax of just five cents per cigarette pack. Many of their Lebanese Shiite buddies live in the Detroit area, where the State of Michigan charges 75 cents per pack. All they had to do was drive a van the 680 miles from Charlotte to Detroit, a 13-hour trip, carrying 800 to 1,500 cartons of cigarettes, and they would net upwards of $3,000. The scam required no special skills, and it made good use of existing pro-Hezbollah networks.

By early 1995, the smuggling operation was in place. The Hezbollah group bought tens of thousands of cigarette cartons at North Carolina's many tobacco outlets, loaded these into rental vans, made a quick round trip to Detroit, and returned the van. In the period 1996-99, Hammoud alone bought nearly $300,000 worth of cigarettes on ten credit cards. The smugglers spent some of the earnings on themselves; Hammoud lived in a middle-class neighborhood, another suspect bought himself two luxury cars, and still others started what the affidavit terms "semi-legitimate" businesses: a tobacco shop to acquire cigarettes in bulk and a Lebanese restaurant to launder the resulting funds.

Starting in 1996, they also sent large sums to Hezbollah. No estimate is available for the total amount transferred, but the affidavit charges Hammoud and four others with smuggling currency and indicates that just one suspect, Ali Hussein Darwiche, sent over $1 million. In addition, several of those arrested stand accused of sending technical materials such as digital photo equipment, computers, global positioning systems, and night-vision goggles to Lebanon. Not surprisingly, one informant states that Hezbollah "sanctioned" the Charlotte group's criminal activities.

But the cigarette scam was too obvious, especially as the smugglers kept getting arrested for driving offenses, and having large numbers of cigarettes (121,500, 436,500, 1,412,400) and dollars ($17,000, $45,922) confiscated. By 1996, the authorities figured out what was going on. A slew of local, state, and federal agents investigated, and made further discoveries.

First, cigarette-running turned out to be just a part of a larger pattern of criminal activity. Nearly all of the Lebanese suspects reached the U.S. through deception, either visa forgery or bribing a State Department official. This bunch lied about everything - claiming to speak English when they could not, creating children out of thin air, asserting the existence of close relatives living in the U.S. They nearly all contracted fake marriages, with one man arranging for himself, his brother, his sister, and her husband each to marry Americans. (Curiously, the Lebanese men paid around $3,500 each to the American women, but a Lebanese woman paid just $1,500 to an American man.)

Once settled, the Lebanese suspects began a minor crime wave. They relied on fraudulent Social Security numbers, passed bad checks, used stolen credit cards, passed stolen goods via mail drops, and engaged in forgery. One gang member, known for his ability to take on multiple identities, used so many false names that he had to pull a book out of a friend's safe and study it before going to the bank. He also became a specialist in "busting out" of credit cards - making half a million dollars since 1995 by getting a high credit limit, charging on it to the maximum, then disappearing without paying it off.

Tax returns from gang members were virtuoso exercises in creative accounting: Hammoud and his fake wife Tsioumas made bank deposits in 1997 totaling $737,318, but reported total wages of just $24,693. The next year, another conspirator deposited $90,903, but listed no income at all. Hammoud's cousin owned a house-painting company; naturally, he employed illegal aliens to staff it, paid them under the table, and skipped on taxes. These are not just crooks, but a whole subculture steeped in criminality.

Also, law enforcement observed a preparation for violence. Associates of the suspects built up an arsenal, including a fully automatic AK-47-style assault rifle, with which they, along with Hammoud, regularly practiced-in what a witness described as "paramilitary-style training" in a remote shooting range east of Charlotte.

Finally, on July 21 of this year, about 250 law-enforcement officers swooped down on the group, arresting 17 in the Charlotte area and one in Michigan. Eleven are Lebanese Muslims, seven are the American citizens who took money for phony marriages. Charges include conspiracy to launder money, conspiracy to traffic in contraband cigarettes, immigration-law violations, and attempted bribery. Pending the results of a search now under way of businesses, cars, computers, and the like, other expected charges include RICO fraud and providing material support to Hezbollah, a designated foreign-terrorist organization. These are serious charges: Cigarette smuggling carries a maximum sentence of five years in prison per charge and a $250,000 fine. Money-laundering carries a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison per charge and a $500,000 fine.

The arrests were top news in Lebanon, where Hezbollah predictably dismissed the charges: "Hezbollah does not have any organized group" in the United States, declared Na'im Qasim, its deputy leader. He attributed the arrests to American officials' "need to create an imaginary victory" to make up for their defeats.

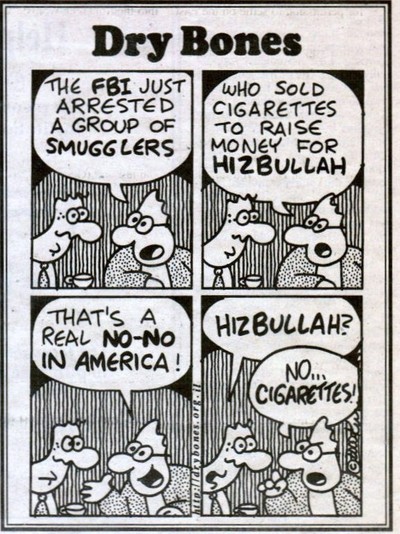

Dry Bones brings his usual cynicism to the Charlotte cigarette case. |

First, it confirms the inaccuracy of Islamist whining about American bias against Muslims. (One friend of the suspects told reporters, "The FBI took the Koran from my home. It just shows the real reason they are doing this"; the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee warned that their treatment "could lead to discrimination and hate crimes.") Immigration and law-enforcement authorities were excessively lenient; note how Hammoud kept beating the system.

Second, the Charlotte case again confirms that Islamist money is flowing from North America to the Middle East, not the other way around. Besides Hezbollah, other organizations funded from here include Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and the Algerian radicals. Middle Eastern governments note this pattern with alarm (Tunisia's president protests that the U.S. has become "the rearguard headquarters for fundamentalist terrorists"), but it has yet to be taken seriously by American leaders. How many more Charlotte-like webs are out there?

Third, the Lebanese suspects showed a contempt toward the U.S. that bordered on the bizarre. Though acting on behalf of a devoutly Muslim organization, they felt entitled to break American laws at whim, without taking even elementary precautions. One defendant charged $45,677 to one credit card for cigarette purchases in a single calendar year; on trips to Detroit, the alleged smugglers paid for gasoline along the way with charge cards, not even trying to hide their movements. Even after arrest, they remained arrogantly unconcerned; according to the Charlotte Observer, at their court hearing, the defendants "smiled, laughed and made jokes. They asked which of their homes, cars and bank accounts had been seized by the government." This nihilism, quite common among uneducated Islamist immigrants, portends trouble.

Fourth, in this case, as in so many other instances of would-be terrorist violence, the authorities bungled matters; if not for alert local officers piecing suspicious activities into a pattern, the scam would still be going on. The INS showed itself to be hapless, not seeing through one fake marriage after another, losing records, and allowing deportees to disappear without a trace. The State Department proved susceptible to bribery. The FBI knew nothing until late in the game. This is frequently the pattern: In at least five cases over the past 15 years, the local cop with eyes open was the key to stopping a major terrorist action. And while lucky breaks are very welcome, it is dismaying to see national institutions caught off guard.

It is even more dismaying to look at this bunch of criminal aliens and political extremists, many of whom have been expelled more than once from the U.S., and find them still here. Given this history, it's a pretty safe bet that most of them will still be here another eight years from now, probably joined by an even larger number of their like.

June 21, 2002 update: A jury in Charlotte convicted Mohamad Hammoud, 28, and his brother Chawki, 37. Mohamad faces up to 155 years in prison and Chawki faces up to 70 years.

July 5, 2006 update: Mohamad Hammoud has spent nearly six years behind bars, serving a sentence that runs through 2135. But he hopes to leave prison in a few months. That's because his case is among hundreds the U.S. Supreme Court sent back to courts following its decision in 2005 to abandon federal sentencing practices. The Supreme Court said federal judges no longer have to follow the guidelines that Congress designed in the 1980s to make prison terms tougher and more uniform. The guidelines are now merely advisory—not mandatory, as before.

U.S. District Judge Graham Mullen in February 2003 sentenced Hammoud to 155 years in prison but must review his sentence, likely within a few months. "I imposed the sentence that was called for at the time by the guidelines," Mullen told the Charlotte Observer. "I don't know what I'm going to do this next time."

Oct. 6, 2007 update: A person identifying himself as Chawki Hammoud, one of the convicted members of the Charlotte group, has written into this page to give his views on the case. Mar. 7, 2009 update: He has written many more times to explain his position, often in argument with Hilda E. Davis.

May 5, 2010 update: Michelle Malkin establishes the pattern of fake marriages at "The jihadists' deadly path to citizenship."

June 12, 2010 update: And Deroy Murdock establishes the pattern of tobacco tax fraud funding terrorism in the New York Post at "How tobacco tax feeds terror."

Jan. 27, 2011 update: Mohamad Hammoud's sentence was reduced from 155 to 30 years in prison on his arguing that he helped the non-terrorist side of Hizbullah (i.e., helping orphans and poor people) and his expressing remorse. "I made a huge mistake," he told Judge Mullen. "I'd betrayed the country that gave me a lot. I'm sincerely sorry. I paid a big price for this. I lost everything but hope and faith. ... Give me a chance to go back to my elderly mother and get a wife and have a family." Hammoud, 37, has spent about a decade in prison.

May 16, 2012 update: Not content with the reduction from 155 years in prison to 30, Mohamad Hammoud says that even 30 years is disproportionately heavy in comparison with other, similar cases. Federal prosecutor David A. Brown Sr. replied at the hearing that the the 30-year sentence is too light: "We think the facts, the record, warrants a life sentence."

Feb. 3, 2016 update: The cigarette-running scam by Middle Easterners continues: The U.S. Attorney's Office of the Eastern District of North Carolina announces today that "Nine Arrested for Conspiracy to Traffic in Contraband Cigarettes."

June 15, 2023 update: Hammoud walked out of prison after serving 23 years of his sentence, announcing that he "would be proud" to send money again to Hezbollah.

Feb. 14, 2024 update: A ban on menthol cigarettes is expected to profit Hezbollah, as Adam Kredo explains in "Biden Admin Has No Plan To Prevent Hezbollah From Cashing In on Menthol Cigarette Ban."