Imagine that an Islamist central command exists — and that you are its chief strategist, with a mandate to spread full application of Shariah, or Islamic law, through all means available, with the ultimate goal of a worldwide caliphate. What advice would you offer your comrades in the aftermath of the eight-day Red Mosque rebellion in Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan?

Probably, you would review the past six decades of Islamist efforts and conclude that you have three main options: overthrowing the government, working through the system, or a combination of the two.

Islamists can use several catalysts to seize power. (I draw here on "Waiting for the Other Shoe to Drop: How Inevitable is an Islamist Future?" by Cameron Brown.)

- Revolution, meaning a wide-scale social revolt: Successful only in Iran, in 1978–79, because it requires special circumstances.

- Coup d'état: Successful only in Sudan, in 1989, because rulers generally know how to protect themselves.

- Civil war: Successful only in Afghanistan, in 1996, because dominant, cruel states generally put down insurrections (as in Algeria, Egypt, and Syria).

- Terrorism: Never successful, nor is it ever likely to be. It can cause huge damage, but without changing regimes. Can one really imagine a people raising the white flag and succumbing to terrorist threats? This did not happen after the assassination of Anwar Sadat in Egypt in 1981, or after the attacks of September 11, 2001, in America, or even after the Madrid bombings of 2004.

A clever strategist should conclude from this survey that overthrowing the government rarely leads to victory. In contrast, recent events show that working through the system offers better odds — note the Islamist electoral successes in Algeria (1992), Bangladesh (2001), Turkey (2002), and Iraq (2005). But working within the system, these cases also suggest, has its limitations. Best is a combination of softening up the enemy through lawful means, then seizing power. The Palestinian Authority (2006) offers a case of this one-two punch succeeding, with Hamas winning the elections, then staging an insurrection. Another, quite different example of this combination just occurred in Pakistan.

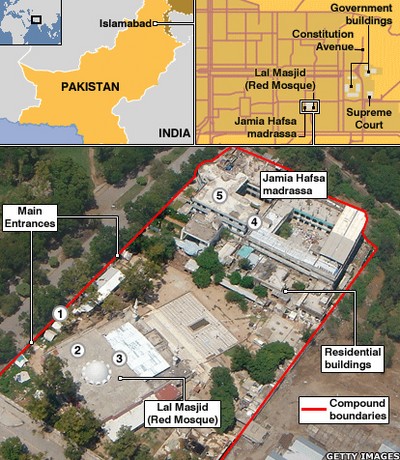

The Red Mosque (Lal Masjid) complex sits at the heart of official Islamabad, the capital city of Pakistan, amid the country's ruling institutions. |

In April, the mega-mosque's deputy imam, Abdul Rashid Ghazi, announced the imposition of Shariah "in the areas in our control" and established an Islamic court that issued decrees and judgments, rivaling those of the government.

The mosque then sent some of its thousands of madrassa students to serve as a morals police force in Islamabad, to enforce a Taliban-style regime locally with the ultimate goal of spreading it countrywide. Students closed barbershops, occupied a children's library, pillaged music and video stores, attacked alleged brothels and tortured the alleged madams. They even kidnapped police officers.

The Red Mosque leadership threatened suicide bombings if the government of Pervez Musharraf attempted to rein in its bid for quasi-sovereignty. Security forces duly stayed away. The six-month standoff culminated on July 3, when students from the mosque, some masked and armed, rushed a police checkpoint, ransacked nearby government ministries, and set cars on fire, leaving 16 dead.

This confrontation with the government aimed at nothing less than overthrowing it, the mosque's deputy imam, Abdur Rashid Ghazi, proclaimed on July 7: "We have firm belief in God that our blood will lead to a[n Islamic] revolution." Threatened, the government attacked the mega-mosque early on July 10. The 36-hour raid turned up a stockpiled arsenal of suicide vests, machine guns, gasoline bombs, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, anti-tank mines — and letters of instruction from Al-Qaeda's leadership.

Mr. Musharraf termed the madrassa "a fortress for war." In all, the revolt directly caused more than 100 deaths.

Mosques have been used as places for inciting violence, planning operations, and storing weapons, but deploying one as a base to overthrow the government creates a precedent. The Red Mosque model offers Islamists a bold tactic, one they likely will try again, especially if the recent episode, which has shaken the country, succeeds in pushing Mr. Musharraf out of office.

Our imaginary Islamist strategist, in short, can now deploy another tactic to attain power.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Oct. 14, 2007 update: The Lal Masjid story is not over, reports the Washington Post today in "Pakistan's Embattled Mosque Reopens With Fresh Momentum." An excerpt:

Three months after a bloody commando raid shuttered a haven for radicalism in the heart of this mild-mannered city, the Red Mosque is open again. And in some ways, little has changed.

At prayers this month, calls for Islamic revolution once again echoed from the minarets. Worshipers talked of overthrowing the Pakistani president, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, in favor of a Taliban-style government. Many wore the red knit prayer caps long favored by Abdul Rashid Ghazi, the firebrand cleric who was killed in the last hours of a nine-day standoff that transfixed Pakistan and seemed to embody the country's struggle with religious extremism.

But here's what was different at the Red Mosque: The crowd that turned out for prayers, relatively modest in size before the siege, spilled out of the mosque and into the courtyard. It continued down the street and filled an adjacent park. Afterward, impassioned worshipers talked about how they had come to honor the "thousands" who had died. (Government estimates put the number of dead at 103.) They walked the adjacent grounds where the girls' madrassa, or religious school, once stood, sifting the rubble for bits of bloodstained masonry. And they said a special prayer for the Red Mosque martyrs, at which point almost everyone began to weep.

The government had hoped that raiding the Red Mosque would strike a powerful blow against radical religious groups in Pakistan. Instead, the mosque has become a memorial, a rallying cry and a propaganda tool for those groups, giving them more recruits and fresh momentum to unleash vicious attacks. Al-Qaeda leaders Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri have both dwelt on the Red Mosque in recordings that call for jihad against Musharraf. Their pleas have been answered in a surge of violence that has claimed more than 1,000 lives and has turned even more Pakistani territory into hostile terrain for the country's army.

Until a couple of weeks ago, the government could at least boast about the tactical victory of retaining control over the mosque itself. But after an aborted reopening in July that ended with the government-appointed cleric fleeing an angry mob, the mosque was returned to the group that operated it before the raid.

On Oct. 3, policemen peeled back layers of barbed wire, and forklifts hoisted away the roadblocks that had encircled the mosque for months. Hundreds of followers of Ghazi and his brother, the imprisoned Maulana Abdul Aziz, streamed in, many flashing victory signs.

Apr. 18, 2009 update: The Lal Masjid imam, Abdul Aziz Ghazi, released from nearly two years of house arrest, returned to the mosque yesterday and renewed the call for the application of Islamic law in Pakistan. "If the government wants peace and stability, it should adopt the Islamic system," he said. "But if it chooses the path of aggression and force, it will further aggravate the situation." One can expect much more trouble ahead from this mosque.

Dec. 19, 2014 update: The massacre of 132 schoolchildren by the Taliban in Peshawar on Dec. 16 has led to unheard-of problems for the Red Mosque. Declan Walsh reports from Islamabad:

Only a week ago, the Red Mosque seemed a nearly untouchable bastion of Islamist extremism in Pakistan, a notorious seminary in central Islamabad known for producing radicalized, and sometimes heavily armed, graduates.

On Friday evening, though, the tables were turned when hundreds of angry protesters stood at the mosque gates and howled insults at the chief cleric — a sight never seen since the Taliban insurgency began in 2007.

What has changed is the mass killing of schoolchildren, at least 132 of them, slain by Pakistani Taliban gunmen in a violent cataclysm that has traumatized the country. …

Protest leaders believe that the public will support them. "This will become a protest movement against the Taliban," one organizer, Jibran Nasir, thundered into a microphone outside the Red Mosque on Friday. … The tide of outrage has encouraged progressive Pakistanis, increasingly marginalized for years, to speak up.

Outside the Red Mosque on Friday, protesters waved placards mocking the chief cleric, Maulana Abdul Aziz, who had enraged many by refusing to condemn the Taliban attackers during a television interview. "Run, burqa, run" read one sign, in a reference to Mr. Abdul Aziz's attempt to slip through a military cordon in 2007 while disguised in a woman's concealing garments. …

"The Red Mosque has become a factory of terror and hatred," said Bushra Gohar of the Awami National Party, a Pashtun political party that has suffered countless Taliban attacks.