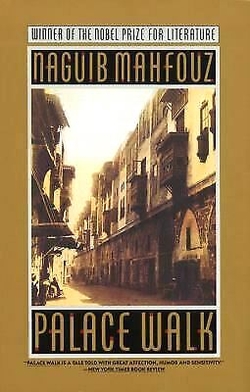

Palace Walk is the greatest novel of Naguib Mahfouz, the Noble Prize winner for literature in 1988; and it and the two other parts that round out the Cairo Trilogy may well be the masterpiece of Arabic literature in the twentieth century.

Palace Walk is the greatest novel of Naguib Mahfouz, the Noble Prize winner for literature in 1988; and it and the two other parts that round out the Cairo Trilogy may well be the masterpiece of Arabic literature in the twentieth century.

In Palace Walk (the name refers to a major street in the old part of Cairo), Mahfouz details the process of modernization in Egypt from the ground up through the story of a single Cairene family, the Abd al-Jawads, in the course of a single year, 1919. The implications are momentous and the tale is enthralling - at least until it weakens under the weight of its own symbolism two-thirds of the way through.

Ahmad, the father, is a prosperous 45-year-old merchant who lives a remarkable double existence. At home, he dominates his family through authoritarian rule and absolutist morality. Not only does he enjoy total jurisdiction over the family, but he routinely demands acts of servility of them: the children must kiss his hands when he is angry with them; his wife, Amina, sits by his feet each night when he returns home from his carousing to take off his shoes and socks. Ahmad's other personality comes out with customers, friends, and mistresses. With them he is witty and charmingly dissolute - the favorite lover of many chanteuses and ever the life of the party.

While deeply hypocritical, Ahmad does not feel so, and Western readers will undoubtedly find his unapologetic outlook one of the two most alien features of Egyptian life seven decades back.

The other is the astonishing position of women. It is one thing to know in the abstract that women were secluded and compelled to accept their husband's behavior, come what may; it is quite another to learn specifically about Ahmad's wife Amina. With a servant and a private bath, she had no need to go out of the house, and Ahmad simply forbade her to show her veil in public. In twenty-five years of married life, Amina stepped outdoors only to visit her mother on rare occasions, and even then was closely chaperoned by her husband.

Then there is the double standard. Ahmad went out every single night and often did not return until dawn, but no matter what the time, Amina awaited him and served him. Once, in the first year of their marriage, she expressed displeasure at Ahmad's outings, to which he replied: "I am a man. The matter is settled; I will not accept any comments on my behavior. You must obey me and take care not to compel me to discipline you." Amina then "learned from this and the other lessons that followed it to endure everything - even the presence of goblins - in order not arouse his anger. She was supposed to be obedient without restriction or condition; and she was."

Together, female seclusion and the double standard lead to the extremes of marital life realized in the Abd al-Jawad family. The husband spent days and evenings out, enjoying the cheerful company of male peers and loose women, while the wife for decades remained at home. This arrangement clearly could not survive modernization.

And indeed it does not. Each of the couple's five children challenges some aspect, large or small, of the parents' lives. The two most important points of friction concern family relations and sexual attitudes.

According to Mahfouz, the First World War signaled major changes in the traditional Muslim family structure. When Fahmi, the second son, refuses to comply with Ahmad's order to stop his nationalistic activities, he acts as a modern son. Fahmi is not merely disobedient; he is inspired by moral principles that Ahmad can neither share nor overrule through the force of personal authority. Such a conflict between generations was almost inconceivable in the more static society of earlier periods, when both father and son would have been similarly attuned to the traditional loyalties. Once the precedent has been set, one expects repetitions to recur with increasing frequency and diminishing justification. As Ahmad's power diminishes, family relations are on their way towards modernity.

Zaynab, briefly the wife of Ahmad's eldest son, wants changes in her position as woman. She insists on going out in the evening with her husband; Amina, the traditional woman, predictably leads the opposition to this notion (for otherwise her own decades of acceptance look wasted and foolish). More disruptive yet, Zaynab demands a divorce when she finds her husband with another woman. This may not sound like a surprising response, but it was to Ahmad, raised in an entirely different ethic. "There was nothing strange about a man casting out a pair of shoes, but shoes were not supposed to throw away their owner." The world is changing and each character, regretting this, changes with it.

Mahfouz can be compared to Honoré Balzac in his love for the life of a particular great city, high and low, and his tolerance for the ambiguity in the heart of each human. At its best, Palace Walk is full of insight about the human condition. Its triumph lies in the portrayal of character, particularly the complex figure of Ahmad, whom we might easily judge to be a moral monster. But Mahfouz makes plausible, through multiple points of view and the merchant's own interior monologues, the good opinion held of him by friends, family, and self.

Mahfouz's people are made plain by his great clarity of language, though his verbal strength is slightly hampered in this translation by a choice of words that often seems merely accurate.

The novel's most contemporary aspect, and its weakest, is its ending. Unlike Balzac, Mahfouz lets the story spin on inconclusively, stopping the action at a sobering climax but without giving closure to an event which might have been a satisfying measuring stick for the change in its characters.