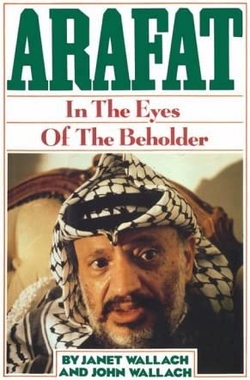

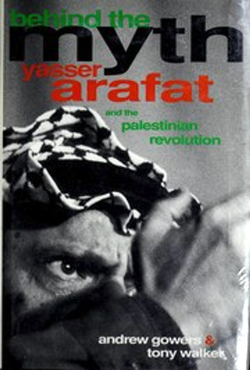

It is not surprising that two major biographies of Yasir Arafat have just appeared, for both were inspired by identical events in late 1988, and then it took a couple of years to be written and published. The heady moment when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) declared a Palestinian state, Arafat renounced terrorism, and the U.S. government opened a dialogue with the PLO. All this seemed to augur a Palestinian state around the corner. To these four authors, it looked like a good time to bet on President Arafat.

It is not surprising that two major biographies of Yasir Arafat have just appeared, for both were inspired by identical events in late 1988, and then it took a couple of years to be written and published. The heady moment when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) declared a Palestinian state, Arafat renounced terrorism, and the U.S. government opened a dialogue with the PLO. All this seemed to augur a Palestinian state around the corner. To these four authors, it looked like a good time to bet on President Arafat.

The passage of time has been cruel to this expectation. Washington broke off the dialogue in June 1990 on account of the PLO's attempted terrorist operation on an Israeli beach. Now that the PLO has announced plans to fight "in one trench" with Saddam Hussein, further diplomatic progress seems unlikely, to put it mildly. Also, the confrontation in the Persian Gulf has severely reduced the PLO's importance.

Still, bad timing notwithstanding, these two biographies are solid studies informed by serious research and extensive interviews. While Arafat's spokesmen boast that fifty-seven books are currently being written about their boss, only two of note have previously appeared in English. Thomas Kiernan's Arafat: The Man and the Myth covers the PLO chairman's early period better than anyone else, but it appeared fifteen years ago. Alan Hart's 1984 study Arafat: A Political Biography is as unreliable as it is sychophantic.

As their titles indicate, both pairs of authors consider Yasir Arafat an enigmatic figure. They portray him as a frenetic, monomaniacal leader who excels at chameleon-like changes. In fact, both books - the Wallachs on page 87 and Gowers and Walker on page 65 - use precisely the same expression, "All things to all men," to describe him. The accounts complement each other in other ways too, sometimes amusingly. When Arafat finally decided to proclaim the "magic words" so long awaited by the U.S. government - "we totally and absolutely renounce all forms of terrorism" - his nervousness caused him to mispronounce his English text. While the Wallachs heard him say "I announce terrorism," Gowers and Walker heard him say the even more silly "I renounce tourism."

As their titles indicate, both pairs of authors consider Yasir Arafat an enigmatic figure. They portray him as a frenetic, monomaniacal leader who excels at chameleon-like changes. In fact, both books - the Wallachs on page 87 and Gowers and Walker on page 65 - use precisely the same expression, "All things to all men," to describe him. The accounts complement each other in other ways too, sometimes amusingly. When Arafat finally decided to proclaim the "magic words" so long awaited by the U.S. government - "we totally and absolutely renounce all forms of terrorism" - his nervousness caused him to mispronounce his English text. While the Wallachs heard him say "I announce terrorism," Gowers and Walker heard him say the even more silly "I renounce tourism."

The main difference between the two books has to do with their agendas. The Wallachs acknowledge that they write as American Jews committed to Israel's security and Palestinian rights; and their goal is to establish (against the great bulk of evidence) that Arafat "wants a peaceful solution [with Israel], a reconciliation of territory for peace." Although they share with the Wallachs an evident bias against the Israeli government, Gowers and Walker do not carry this political baggage, so their goal is to assess the totality of Arafat's achievement and his place in history. The result is friendly but skeptical: "Despite his turbulent career, his life of perpetual motion, Arafat in his early sixties is in some ways a curiously static individual. . . . It may be that he is caught in a holding pattern, like Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, forever condemned to seek and not to find."

The two books read very differently. The Wallachs's account - racing from one country and one year to another, interrupted by breathless updates of their own travels - suffers from an almost comic lack of organization. It also demonstrates an all-encompassing sloppiness: names, foreign words, and historical events regularly get garbled. Anwar al-Sadat was not "a relatively obscure colonel" when he succeeded to the presidency of Egypt (but the country's vice president); the Munich massacre did not take place on the last day of the Olympics (6 days were left); and their dramatic account of a small child in Beirut who pulls the trigger of a Kalashnikov as his father holds the gun, thereby scaring off Israeli war jets, ignores the fact that hand guns can do virtually no damage against modern fighter aircraft.

In contrast, Behind the Myth tells a coherent story. Most fascinating is Arafat's transformation from a nerdy, self-promoting ward captain, racing about Beirut in 1965 in a battered Volkswagen, foisting on journalists press releases with details of imaginary battles with Israel, into what he is today - the leader of the richest irredentist movement in the world, one of the most newsworthy men alive, a dignitary widely treated with the honor due a head of state. Gowers and Walker trace his ascent with skill and dispassion; if you want to understand Yasir Arafat, they tell the story.

Unfortunately, while the Wallachs' study has been published to considerable acclaim in the United States (even President Bush found time to read it) Behind the Myth has not yet found an American publisher. It should.