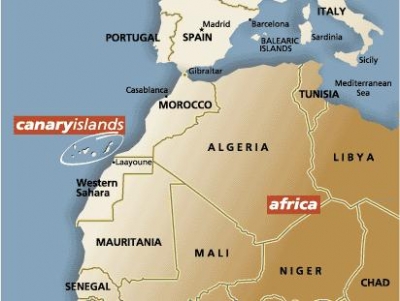

Mauritania, a country in West Africa far from Europe, has become the latest springboard for desperate would-be immigrants to reach Europe. They travel by boat for three days and nights to cover the 500 miles from Mauritania's long coastline to the Canary Islands, which is Spanish soil. Once in the Canaries, the whole of Europe lies before them.

The voyage is perilous and over a thousand Africans have died during the past four months while sailing the Atlantic Ocean in traditional wooden fishing canoes called pirogues, normally used for net-fishing expeditions. The vessels are uncovered, are usually powered by a single outboard engine, and rarely carry navigational or emergency equipment. Up to 40 per cent of those who attempt the crossing from Mauritania may not make it. Still, 8,519 Africans reached the Canaries in 2004, 4,751 in 2005, and over 3,500 so far in 2006. The Spanish government has detained at sea more than 1,000 migrants in the last 10 days alone.

Mauritania, one of the world's poorest countries, is unable to handle the influx. Its prime minister, Sidi Mohamed Ould Boubacar, said that the country. "can't control its borders and needs help against this massive wave of immigrants. We can't resist this growing pressure. We need help of all types: planes, boats, vehicles." He said the authorities arrested 3,900 migrants in 2005 and already 1,200 in the beginning of 2006. "What is arriving is unimaginable."

Migrants in a high-sided wooden boat that set out from Mauritania and was intercepted by the Spanish coast guard off the Canary Islands. (Gustavo Gonzalez/ AFP/ Getty Images) |

|

The increase appears to result from the crackdown at Ceuta and Melilla. Unable to reach there, the Canaries became the destination of choice. "The smugglers have just moved the boats south because the Moroccan police and border patrols are now stronger," says Manuel Pombo, a Spanish ambassador-at-large. Unable to travel from Morocco has made the journey much longer and more hazardous.

A delegation of Spanish officials has arrived for talks to establish an "urgent plan of co-operation" by which the Spanish government helps its Mauritanian counterpart patrol its coastline and establishes centers to process migrants in the country. Between 10,000 and 15,000 Africans, mostly from Senegal and Mali, are thought to be in Mauritania planning to get to the Canaries. (March 19, 2006)

Apr. 1, 2006 update: In an on-the-scene report, the Washington Post's Kevin Sullivan compellingly fleshes out this abstract problem by telling the story of a Senegalese electrician and father of two named Magat Jope, who made the three-day bus journey to Nouadhibou, a seatown of 90,000 people and the second-largest city in Mauritania:

Wealthy beyond belief in the eyes of destitute people almost everywhere, the European Union also draws an illicit flow of migrants from the former Soviet Union, China, Latin America and the Arab world. Together, these tides of people are adding up to one of the most significant migrations of current times. The new route from Africa appears to be far more dangerous than the older ones, but people keep coming. "If you are as poor as we are, you are not afraid of death," said Jope, 34, an electrician and polite father of two. "I want a house. I want to educate my children. The risk doesn't matter." …

On any day, the town's markets are filled with traders in flowing robes selling oranges and dates. There are nearly as many donkeys as cars on the rutted streets. Along the beaches, hundreds of open fishing boats deliver cargos of mullet, shark and bright-colored shellfish. Jope soon became aware there were many people like him in town, outsiders trying to blend in, avoid the police and find boats heading to the Canaries. They were from Mali, Gambia, Nigeria and other West African countries. A population boom and ballooning joblessness in many African countries, driven in part by a wave of subsistence farmers moving from their villages into cities, has caused thousands to risk the journey here.

Ahmed Ould Haye, local head of the Red Crescent, the Muslim counterpart of the Red Cross, estimated that about 15,000 migrants were milling around here waiting to go to the Canaries. Many work as laborers or fishermen to earn money for the voyage, which typically costs $1,200, Haye said. Some of them pool their funds and buy a narrow boat shaped like a canoe, pointed at both ends. Some pay fishermen to take them. Others deal with middlemen who arrange boat and skipper. Local authorities say a boat leaves nearly every night, jammed with as many as 60 people.

Finally, on Feb. 1, 2006, he began the sea journey:

he walked down to the beach in a cold winter breeze, paid about $10 for a worn orange lifejacket and stepped into a 40-foot fishing boat with 34 other people. He handed the captain $1,100. The canoe-like boat chugged away from shore powered by a 40-horsepower outboard motor and steered by the captain using a hand-held global positioning device.

Almost immediately, Jope said, passengers who were not used to being on the water began vomiting. The smell was overpowering. Jope, over six feet tall, found there was barely enough room for people to sit. His legs and ankles swelled so much that he couldn't straighten them. People prayed and talked quietly, he recalled. There was plenty of food and water, but no one could sleep, and the leaky boat needed constant bailing.

Four days out, they were intercepted by a Moroccan naval vessel. Sailors tied a line to the bow of the immigrants' boat and towed it for three days back to Nouadhibou. All the way, Jope felt devastated. When they approached the town, everyone on the boat jumped overboard and swam to shore, then ran away to avoid being detained and sent home. He never saw the captain again, and his $1,100 was gone.

Despite this experience, "Jope said he planned to go home to Senegal, pay his mother back, save some more, then come back to Nouadhibou to try again."

Rickard Sandell, an immigration specialist at the Real Instituto Elcano in Madrid, is quoted observing that "The frontier between Africa and Europe is turning into one of the most dangerous migratory passages ever seen." Further: "We are just seeing the start of something much, much bigger."

Apr. 12, 2006 update: "Spain to free 1,500 illegal immigrants into Europe" reads the Daily Telegraph headline. Some 3,800 illegal immigrants landed in the Canary Islands since the start of 2006 and Spanish authorities have been repatriating some of them to Mauritania by chartered aircraft.

But, under its liberal immigration laws, illegal migrants can be held for a maximum of 40 days. If officials then fail to establish their nationality, or discover that they come from a country such as Mali which has no repatriation agreement with Spain, they must be released. Most illegal arrivals will therefore have to be set free, officials said. Once released on the Spanish mainland, the migrants can make their way through continental Europe because of the border-free Schengen zone.

The paper indicates that most of them hope to make their way to Britain, France, and Italy.

Apr. 29, 2006 update: Mauritania finds itself hosting not only African-would-be-immigrants-to-Europe but also South Asians with the same ambitions, Heidi Vogt documents today in an Associated Press story today from the northern town of Zouerat.

Dozens of Indians, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis have turned up in Zouerat over the past 18 months, having been abandoned by the smugglers in the Sahara with little water, no food and no passports. No one knows how many others have died in the empty desert. … The Asians say they paid around $15,000 each to be smuggled to Europe. Now they are reduced to going from door to door offering to wash clothes and do odd jobs for food or money. Undocumented, many deep in debt to the smugglers who hold their passports, they have been living in a twilight zone between the homes they left and the homes they dreamed of finding. … The road to Europe is a long one - a 6,000 mile flight from India to West Africa, and then the illegal leg begins - some 1,000 miles over the Sahara in four-wheel drive vehicles and onward to a North African port from which the migrants will try to sneak into southern Europe in search of work.

Comment: That people who have $15,000 to spend on a one-way ticket will attempt such desperate means to reach Europe points to the depth of the problems the West as a whole now faces in controlling its borders. As I predicted nearly five years ago, the militarization of the frontiers and the use of force to fend off such immigrants is close to inevitable.

May 19, 2006 update: "The calmer seas of early summer [sic – it's still spring, DP] have seen a sharp rise in the numbers reaching the holiday islands," writes Mike Elkin in the Daily Telegraph. "More than 1,400 arrived in Tenerife and Gran Canaria in the past week, while 2,000 have landed this month, mostly from Senegal and Mali, compared with 4,751 in the whole of last year." The Spanish coast guard, which has 3 naval ships and 3 surveillance aircraft watching the seas between Africa and the Canaries, yesterday alone intercepted 7 boats carrying 483 people.

The Spanish government has responded with an urgent appeal for help and with an announcement that it is dispatching diplomats to several West African countries. Foreign Minister Miguel Angel Moratinos said a special ambassador and a team of diplomats would begin "three- to six-month" missions to such African countries as Cape Verde, Gambia, Verde, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Niger and Senegal. Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero sent letters to the leaders of Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, and Mali, asking for help to curb the flow of immigrants.

May 24, 2006 update: The European Union is hearing Spain's pleas. Franco Frattini, its justice and home affairs commissioner, said the Union "will provide operational support as fully as we can to the Spanish government to deal with an urgent and difficult situation." The EU's new external border security agency, Frontex, will send two emergency coordination teams, including surveillance planes, patrol boats, and rapid-reaction aid teams, to the Canary Islands. Eight EU member states (Britain, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Slovenia and Sweden, plus another two whose names are not presently known) will provide soldiers and police officers. Madrid also hopes other EU states will help it set up "reception centers" ("holding pens" would be a more accurate description) in such key transit countries as Mauritania and Senegal to stem the flow of illegals.

In addition, the Spanish government is in discussions with the Senegalese authorities to reduce the influx of illegals setting out for the Canary Islands. But the talks did not lead to a formal repatriation agreement, for reasons that echo the U.S.-Mexican negotiations and point to difficulties to come.

After talks in the Senegalese capital, the Spanish secretary of state for foreign affairs, Bernardino León, said his government believed that illegal immigrants should be sent back to their home countries. "The aim is to increase our cooperation on migration in all areas," León told reporters. "What we need at this time is to speed up these repatriations and for people to realize that we're in a moment of crisis."

But Foreign Minister Cheikh Tidiane Gadio of Senegal made clear that his country would not sign an accord to automatically repatriate those intercepted. Senegal did, however, agree to work with Spain to try to halt departures of boats carrying illegal migrants and crack down on people-smuggling gangs. "There is cooperation, but we haven't signed an agreement," Gadio said at a news conference. However, he said that Senegal's government was willing to assist its nationals stranded abroad, including bringing them home if necessary. A team of Senegalese officials will fly to the Canary Islands to interview illegal migrants held there.

The Senegalese Navy said in a statement Monday that it had seized 19 boats over the weekend carrying 1,500 would- be migrants, including 60 suspected migrant-traffickers.

May 25, 2006 update: "Europe has to wake up and stop staring at its belly button," says Miguel Becerra, a senior policy adviser in the regional government of the Canary Islands. Writing in the International Herald Tribune, Renwick McLean provides some important information on the situation:

First, although the Spanish government vows that all the migrants will be deported back to their countries of origin, illegals intentionally shed all ways of identifying them, so deportation becomes all but impossible. A Red Cross director in Tenerife, Rubén Fernández, concludes that "Most of them will probably be set free." Because of the colonial legacy, most Africans who speak a European language know French or English, so they often set off for France, Britain or Belgium.

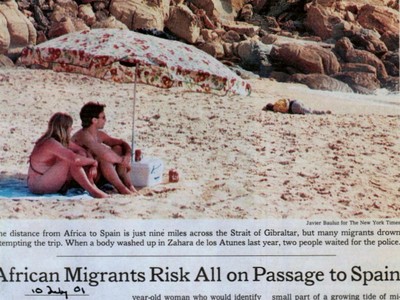

A picture from The New York Times of July 10, 2000, shows an African corpse washed up near bathers on a southern Spain beach. |

Second, a study by the Royal Elcano Institute in Madrid argues that Europe may be on the brink of a flood of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, with potentially historic implications. Rickard Sandell, chief investigator for demography and population studies at the institute, wrote in the report that

Both economic and demographic data provide evidence that this is only the beginning of an immigration phenomenon that could evolve into one of the largest in history. … the mass assault on Spain's African border may just be a first warning of what to expect of the future. The situation is so serious that the possibility of a mass exodus if the African states fail to absorb their rapidly increasing working age population should not be ruled out. Nor can we rule out the possibility of armed conflict as a result of the political unrest that is likely to follow from a lack of effective management of the unprecedented increase in the labour supply

Third, as the Mauritanian police begin to crack down, migrants have begun leaving from Senegal, even further south. This means that the sea journey to the Canaries that some months ago lasted a mere 12-24 hours from Morocco now requires 7-10 days.

Fourth, McLean gives some sense of the sociology of the exodus.

According to Red Cross officials, the migrants typically leave with a pile of life vests, a compass or global positioning system, limited supplies of food and water and a small outboard motor suited more for the gentle currents of a small river than for the waves of the Atlantic. One recent arrival packed 78 migrants into what looked like an enormous canoe. The only method of steering was a rusty piece of iron fashioned into the shape of a rudder and attached to the back of the boat.

"You generally find two types of social classes in the boats," said José Reyes, 31, a Red Cross official in Tenerife who has worked extensively in Africa. "There are the fisherman who don't know how to read, and the middle class ones from the cities, who always have books or magazines in their hands." The educated ones have no idea how to survive at sea or to command a boat, he said, and the fisherman could never afford an outboard motor and a global positioning system. So they come together, with the fishermen handling the boats and the others providing the supplies. …

"The motors are in terrible condition, and if they break, they are at the mercy of the currents and can end up anywhere," said Fernández of the Red Cross. "We have no idea how many have been lost, because the currents flow away from the islands and out towards the Americas," he said. "But surely many have been lost."

In a second International Herald Tribune article, Dan Bilefsky looks at the European Union's disarray in the face of the Canary Island illegals. In particular, the European Commission, for the second time in two years, could not agree on the African countries to which would-be migrants can be sent. Draft lists have included Benin, Botswana, Cape Verde, Ghana, Senegal, Mali, and Mauritius. But Mali will be excluded because of its practice of female genital mutilation.

May 30, 2006 update: I published a column today, "[West Africa:] New Route to the West," that reviews this problem and places it in its larger context.

Also today, 732 illegal immigrants reached the Canaries in eleven boats, a single-day record. And the joint Spanish-Mauritanian patrol launched on May 15 intercepted its first boat, with 37 would-be immigrants aboard, near the northern point of Mauritania.

June 7, 2006 update: For the first time, origin, transit, and destination countries have come together to seek solutions to the African-to-Europe immigration problem. Meeting for two days in Dakar, Senegal, senior officials from more than 50 Europe and Africa countries are working on an integrated multinational strategy and action plan. Of course, a tension exists between enforcement (the European priority) and root causes (the African priority), with the current draft calling for more of both. If all goes well, the plan will be adopted by European and African ministers at a migration summit July 10-11 in Rabat, Morocco.

Also of note: Senegal has suspended repatriation flights from the Canaries, saying its migrants had been mistreated by Spanish authorities, which Madrid denies.

June 10, 2006 update: Reporting on his conversations in Madrid, EU Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security Franco Frattini says that "in Mauritania some 50,000 people are concentrated to try to move north, and in Senegal another 20,000 are ready to go north, to cross the ocean to try to get to the Canary Islands." He also provides a startling statistic: "Only 4 or 5 per cent of asylum-seekers coming to Europe are genuine refugees and are accepted," he says. "More than 90 per cent are rejected, so they have to be repatriated."

A tourist gives water to an African immigrant landed on Tejita beach in Tenerife, Canary Islands. |

They were given first aid by holidaymakers and locals who took some of the most severely dehydrated to hospitals near the town of Granadilla in their cars. "It was totally spontaneous," a local police officer, Javier Melián, told El País newspaper yesterday. "Every immigrant must have had four or five people looking after them. The beach was full of tourists."

Foreign sunbathers, especially Germans, were among those who helped while Red Cross units and the local police made their way to the beach on the southern coast of Tenerife. The tourists helped the immigrants wade through the last few metres of water on to the beach, gave them water to drink, dry clothes and held towels over them to keep them in the shade. Several children were among those who had to be looked after until the Red Cross arrived.

"We handed out surgical gloves to people in case the immigrants had illnesses, but they didn't really care about that," Mr Melián said. "I was especially impressed by the young people, who gave them their things and helped, even though they could not understand a word they said."

Aug. 22, 2006 update: The rising numbers of illegal African immigrants arriving in the Canaries – 512 on August 18, 324 on the 19th, 432 on the 20th – is exacerbating the crisis, prompting the Spanish government to undertake urgent diplomatic initiatives in Africa, including a doubling of development aid from the present 650 million.

Sep. 1, 2006 update: An anti-Spanish backlash is in the making, writes David Rennie in the Daily Telegraph's blog:

the European Commission finally turned round and said Spain should take some of the blame for the surge in illegal African migration to the Spanish Canary Islands. It was high time, frankly, to call for a reality check in Spain's months-long campaign of demanding EU aid, EU boats, planes and police patrols, to help try to control this year's unprecedented influx of migrants from Mauritania and further south (first written about, as far as the British press is concerned, by this paper).

The EU justice commissioner, Franco Frattini, gave a joint interview to several Spanish papers, and said – in a nutshell – that the Socialist government helped cause this crisis, with its amnesty for hundreds of thousands of illegal migrants, last year. Spain granted the amnesty without first controlling black-market labour or consulting EU leaders, enraging countries like Germany, who suspected that many of the regularized migrants would soon be turning up in their country, thanks to the border-less Schengen zone. It also seemed likely to be what immigration officials call a "pull factor" for fresh migrants.

To quote Mr Frattini: "If a member state opens a process to make immigrants legal without controlling black market labour, it encourages illegal migrants to enter this country and move on to another." Spain introduced a three-month amnesty for illegal immigrants in February 2005, saying it was the only way to regain control of a chaotic situation. Around 600,000 people took part in the plan.

Comment: The extremism and recklessness of the Zapatero government – so evident in other areas of public policy – are finally getting exposed with respect to immigration too.

Sep. 5, 2006 update: Records exist to be broken. Twelve boats (or more) of illegals reached the Canary Islands in the span of 36 hours this past weekend – 674 people on Saturday and 522 on Sunday. More than 20,000 Africans and others have arrived, including around 6,000 in August, compared to 4,751 for all of 2005.

Sep. 9, 2006 update: Muammar al-Qaddafi has added his own unique take to the illegal immigration problem, telling European states to pay 10 billion a year to Africans "if it really wants to stop migration toward Europe."

Sep. 13, 2006 update: As illegals are arriving to the Canaries in 2006 at five times the rate they did in 2005, Madrid government has declared they will all be repatriated. In this spirit, Spain's secretary of state for foreign affairs, Bernardino Leon, has held urgent talks in Dakar with the Senegalese president, Abdoulaye Wade, and Interior Minister Ousmane Ngom to find ways to stem the flow immigrants. Leon specifically called for a crackdown on people-smugglers. But when asked if the Spanish authorities plan to repatriate Senegalese, Leon demurred.

Sep. 15, 2006 update: The Canaries having become famous as the weak link in Europe's immigration fence, a first boat carrying 216 Asian immigrants, apparently Pakistanis, is about to land there.

Also of note: the Spanish interior minister, Alfredo Perez Rubalcaba, said 59,000 illegal aliens have been expelled from Spain in 2006, with the pace ever-accelerating.

Oct. 11, 2006 update: The Spanish government has signed agreements with Guinea and Gambia in the effort to stem illegal immigration by persuading young Africans to stay at home. Each West African state will receive £3.4 million to prevent migrant departures and support long-term development. In return, Madrid expects the two governments to help identify their nationals, so they can be repatriated. The agreements met with derision, however, when it became known that only 156 of the illegals arriving in the Canaries in 2006 are thought to originate from Guinea and 500 or so from Gambia. La Razón (the Spanish daily where my articles appear every Sunday) calculated that repatriating each Guinean costs the Spanish taxpayer £22,000.

Nov. 19, 2006 update: The misery and dangers facing African would-be immigrants as they make the 1,250-mile crossing by pirogue from Senegal to the Canaries comes vividly to life in Hannah Godfrey's report from a Senegalese seacoast village called Diogue, in the Casamance region of southern Senegal. She writes in the Observer, "On a voyage of peril to the mirage of Europe":

Edward and Isaac managed to get on a boat leaving from Diogue, and were off the coast of Mauritania when a huge storm blew up. Everyone in the boat - including the 'captain' - was so terrified that they decided to head back to Senegal. Two people died in the course of the voyage from exhaustion and sickness. Their bodies were thrown overboard. 'It was like we had become animals,' Edward says afterwards. 'I realised that it wasn't worth degrading ourselves, and risking our lives just to get to Europe, even though it means the end of our hopes of finding a way out of the dead end we are in. There is no work for us back home.' They know that the jobs they left in Gambia to go to Diogue will have been filled by others.

Not only have they lost their dream of a better life, Edward and Isaac have also lost the money that they had worked for a year to save up - the man who organised the voyage refused to reimburse them. Now they set off on the long journey back to Ghana. Isaac has a Spanish phrasebook tucked into his plastic bag. Will they make another attempt, once they have got some more money together? 'When we were on that boat we saw into the pit,' he says. 'We were so tightly packed in there that no one could move. There were a number of us who couldn't speak to anyone, because we didn't share the same language. After the storm the supplies of food and water began to run out. Most of us had never been at sea before. We were ill and scared, and then the people started dying...' His voice trails off. 'I can't describe how awful it was. Nothing is worth that.'

Comment: Not for nothing does a 20-year-old in Diogue dub attempts to get to the Canaries "Europe Madness" and "a way of committing suicide."

Nov. 30, 2006 update: Frontex, the European Union new external border security agency, is not proving a great success – in the Canary Islands, Italy has contributed one airplane and one boat, Portugal has contributed one boat. Therefore Franco Frattini, vice president of the European Commission, is talking about the creation of a Europe-wide coast guard. This has obvious advantages, making it possible for Italy, Malta Spain, and other frontline countries to coordinate schedules, pool resources and exchange information. But it faces the EU problem of member states reluctant to relinquish their sovereign control over such a delicate matter as immigration.

Dec. 4, 2006 update: Christopher Caldwell has a 6,000-word essay on this topic in the Weekly Standard, "Europe's Future: The Senegalese (and the Malians, Mauritanians, Gambians, et al.) are coming to Spain—and staying," the first in-depth analysis of this topic in English, so far as I know. Some highlights, starting with the scope of the problem:

Thus far in 2006, 30,000 "boat people" have landed on Canary Island beaches—already six times last year's tally. The great majority come from Senegal. There are also Malians and Mauritanians, Gambians and Guineans, Congolese and Cameroonians, and others whom Spaniards don't usually think of as their neighbors, but who now consider Europe just a hop, skip, and a jump away. There are occasional boats full of Chinese and Bangladeshis, too. Spain isn't the only destination for boats pouring out of other continents. The Italian islands of Lampedusa and Pantelleria have received well over 10,000 boat people this year. Migrants from East Africa, Pakistan, and India are beaching boats launched in Libya on the shores of Malta and Greece. And boats are not the only way to bust into the E.U.—there are also land routes through Eastern Europe, and the majority of immigrants to Europe still get there by flying in as tourists or students and then overstaying their visas.

Then the special Spanish situation:

Spaniards have started to note that, in contrast to previous waves, these migrants seem to be coming to, not through, their country. Spain, which a decade ago thought it had an emigration problem, now finds itself the top immigrant destination on the entire continent. Its population has jumped to 44 million people, thanks to almost 4 million new immigrants. … Spain is now about 10 percent first-generation immigrant, and this has happened overnight. Much of the present migration is to cities. Foreigners make up 19 percent of the population (and 28 percent of the workforce) in Madrid. The Valencia region is 14 percent foreign-born. The Raval area of central Barcelona, where immigrants were exotic up until the early 1990s, is now a "majority minority" neighborhood.

Not only is immigration to Spain more sudden but it is also more severe than elsewhere in Europe:

Its population seems to have lost the appetite for procreation altogether. The average woman has 1.32 children, a figure that would have looked like a misprint to any social scientist before the 1980s. As a result, Spain's native-born population will begin contracting with shocking rapidity after 2014, and it is too late to do anything to stop it. Already Spain has gaping holes in its labor supply. The strawberry fields and clementine groves of Andalusia require tens of thousands of pickers every year. The tomato-growing greenhouses near Almería rely on Moroccan labor, and Eastern Europeans staff many tourist hotels.

In part, this is because

Spain's immigration controls are, by European standards, uniquely lax. Spain is the unlocked side-door of the European Union's house. And since the E.U.'s Schengen agreements eliminated old frontiers between member states almost a decade ago, once you get into Spain, there are no border guards to keep you out of the Netherlands, Germany, or wherever you choose to settle. If you imagine that Senegalese tend to gravitate towards France, where they speak the language and have a big established community, you are wrong. Experts at ENDA Tiers Monde, a Dakar-based think tank, say that France, while still popular for students, is far down on the list of desired work destinations, owing to its rigid labor market and relatively tough immigration laws. Italy and Spain are the countries most attractive to the latest wave of newcomers. …

Spanish laws towards foreigners are generous, and punctilious about human rights. They also invite chicanery. You cannot detain an immigrant for more than 40 days unless you charge him with a crime, and you cannot deport an immigrant unless you know where he comes from. If he can keep his mouth shut for a month or so, or if he can misdirect the bureaucracy until his 40 days have elapsed, he's in like Flynn. A common way to throw authorities off balance is to pretend to be from somewhere else. Since Spain does not have an extradition treaty with strife-torn Ivory Coast, for instance, many of the Senegalese who have arrived by boat in recent weeks have claimed to be from there (even though the two countries speak mutually exclusive sets of African languages). In October, Pakistan demanded that a half dozen boat people (out of hundreds taken off a rusty old freighter and "repatriated" there) be sent back to Spain. They turned out to be from Indian Kashmir, not Pakistanis at all. You have to be pretty unlucky to get repatriated. Of the 30,000 Senegalese who have arrived this year, only 4,000 have been sent back. The others are put on flights to the Spanish mainland, with an expulsion order in their pocket. Such orders are virtually never enforced. For a migrant, this is roughly a 7-out-of-8 chance of settling in Spain indefinitely: excellent odds.

In early 2005, Spain's Socialist prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero made life much easier for Spain's undocumented immigrants. He proposed to amnesty roughly a million of them, provided they could show they had been working in the country for several months. The opposition whittled the number down to about 700,000. Such amnesties were not new. The Aznar government had passed five of them since the mid-1990s. But Zapatero's was simpler and more open to abuse, and bigger than all previous amnesties combined. What is more, by announcing it many months in advance, he opened a window that would lure new immigrants into the country in order to set up a paper trail that would render them undeportable. And because of free movement between European states, the amnesty harvested the fury of politicians abroad, including the French interior minister and presidential hopeful Nicolas Sarkozy. …

But that does not exhaust the reasons to come to Spain. Under a 2000 law, registering with the local census (the padrón municipal) permits access to health care and other services. An immigrant can be eligible for welfare services while existing below the radar of the enforcement authorities. The upside of such registration is that Spain may have a more accurate count of its immigrants than other countries. The downside is that it has rapidly mounting welfare dependency--300,000 immigrants now live off of social benefits. All told, the combination of easy admission and generous welfare has created what the newspapers call an efecto llamada. The most graceful way to translate the term is to say that Spain is not just accepting immigrants, it is summoning them.

Even the refugee camps in the Canaries—while overwhelmed by the waves of newcomers—are welcoming. Authorities have been easygoing about allowing Senegalese elders to organize camp life, and have done their best to ease overcrowding. In addition to the three centers in Tenerife and one in Gran Canaria, other facilities have been adapted to accommodate the overflow. The camp at Hoya Fría had gigantic circus tents erected outside it for much of the summer. A military barracks at Las Raices was converted to migrant housing. So was a discotheque in La Gomera.

Caldwell then looks at the dangerous passage:

There have been 600 cadavers pulled out of African waters this year, according to Froilán Rodríguez, the immigration minister for the Canary Islands. In August, the European commissioner Franco Frattini of Italy alluded to a possible 3,000 dead. Angel Acebes, secretary-general of Spain's opposition Popular party, has thrown out the figure of 6,000. Some boats are lost altogether. The Canary current is where the Gulf Stream turns abruptly south along the African coast and then rushes west, back across the Atlantic. This past spring, a boat filled with immigrants who had left Senegal in January and suffered an engine failure was found floating, its passengers long dead, in waters off Barbados.

Even if everything goes perfectly, crossings are harrowing. These boats run at 5 or 10 knots, which will get you to the Canaries in 7 to 8 days if the weather is good and the seas are calm. There are no toilets and the stink, naturally, is unimaginable. There is no place to lie down and the benches offer nothing to lean back on. This means an almost sleepless week for many people.

But if you get on a bad boat, as 17-year-old Malang Kalela of Ziguinchor did, all bets are off. I met him at the Machado Escuela Hogar, a school for troubled teens near the village of Esmeralda that has been converted into a camp for underage migrants in Tenerife. Both motors on Malang's boat conked out, and only a good captain kept it, and the 80 passengers aboard, from drifting westward into oblivion. It arrived in Tenerife on its thirteenth day at sea, after the food, fresh water, and seasickness pills had run out. Worse, two people had leapt off the boat in the middle of one night, and drowned. Such incidents are common. Many of the migrants have never been at sea before and don't know how to swim..

A few more details on Frontex:

Spain asked for help from Frontex—the European Union border guard launched in 2005. Frontex has two big problems. The first is that it is a Potemkin agency, with a budget of only 15.8 million ($20 million). This makes it a coalition of the willing, and the coalition has not been very willing. Under Frontex's aegis, Spain has deployed one Guardia Civil helicopter to Mauritania and two more to Dakar. There was supposed to be an Italian boat, but as of this fall it was getting repaired. Finland promised to send a plane. There was a Portuguese destroyer operating far out to sea in the Cape Verde Islands..

May 14, 2007 update: As the seas calm and the warm season begins, the Spanish authorities say they are prepared for the immigrants from West Africa.

"Compared with last year, the situation is much more under control," said Marlene Menesis, a spokeswoman for the central government in the Canary Islands, who said efforts by the Spanish Civil Guard and Coast Guard, as well as the European immigration force, Frontex, had helped cut in half the number of arrivals so far this year to just under 3,000. "Many of the boats have barely left ports and reached international waters when they are turned around," Menesis said. José Segura, the central government's representative in the Canary Islands, said the Interior Ministry was planning to send two large ships to help police the archipelago's waters and the ministry issued a statement saying that it had intensified the rate at which it was repatriating illegal immigrants, sending 168 home over the weekend.

Aug. 11, 2007 update: That Spanish confidence appears justified. Only about 6,000 migrants have landed in the Canaries through July 2007, compared to 13,000 a year earlier, apparently the result of improved Spanish maritime surveillance, cooperation from Senegal and other African countries, and rougher seas.

In addition, the Spanish government has implemented a program of legal immigration for African workers. As described by Victoria Burnett in the New York Times, the program "aims to bring hundreds of workers to Spain this year with renewable one-year visas and jobs. Workers on one-year permits may have their contracts extended, at which point they have the right to bring over their immediate family. Ultimately, officials here say, the plan is to bring in thousands of immigrants through the program." The United Nations special representative for migration, Peter Sutherland, called it "advanced thinking in terms of migration policy" and "trailblazing."

Comment: Sutherland may be impressed by the program, but it brings to mind Germany's failed Gastarbeiter agreements starting in 1955 – failed because many of the migrant workers decided not to return home but stayed in Germany.

Aug. 26, 2007 update: A look at Italy and Greece in addition to Spain finds that African immigration has lowered in all three countries, as well as the deaths associated with the hazardous sea crossings. From a New York Times report:

as of the end of July, Fortress Europe reported the number of arrivals to Italy at 5,200 people, compared with 9,389 in the same period in 2006, a drop of 45 percent. … Spain has reported an even greater reduction: official numbers for this year show 7,934 arrivals through July, compared with 17,433 in the first seven months last year. Greece, another major destination for immigrants, is also reporting a drop of 20 percent from last year.

July 13, 2008 update: A new summer means new patterns and new tragedies, report Graham Keeley in Barcelona and John Hooper in Rome for the Observer:

Human rights agencies find a a sharp increase in the numbers of would-be immigrants crossing by sea from Africa to southern Europe, many of them from conflict zones such as Eritrea and Somalia. Indeed, as refugees embark on ever-more perilous routes in ever-smaller boats, 2008 could witness a record-breaking death toll. The port of Almería, almost at the easternmost point of Spain's southern coast, appears to have emerged as the new favorite destination because of its inadequate coastal detection monitors. But the 100-mile journey across the Mediterranean Sea from Morocco means an estimated one in three boats does not reach its destination.

Another growing destination is Lampedusa, the Italian island at its closest just 120 kilometres from the African coast. Most of the refugees landing in Lampedusa, however, make much longer journeys in very primitive craft consisting of two inflated units, a crude wooden deck, and a modest engine sent out by the traffickers without any trained personnel. The migrants rarely know how to operate the craft and often lose their way or sink without a trace.

Aug. 7, 2008 update: The number migrants caught trying to enter Spain illegally in 2008 has declined 7 percent compared to 2007

July 11, 2010 update: The Spanish government is cracking down hard, reports the New York Times today.

The Spanish government, prompted by its partners in a Europe of dissolving borders, has been taking strong measures, doing all it can to seal its southern coast, though. It is installing a $120 million radar system that will form a sort of electronic wall across the strait. The government has also ringed Ceuta and Spain's other enclave on the north African coast, Melilla, with double razor-wire fencing and infrared cameras to keep people from crossing the border illegally. And it has stepped up patrols along the coast.

After anti-immigrant sentiment in southern Spain set off rioting last year, the government began cracking down on Spanish citizens who help the immigrants. Juan Antonio López, a 24-year-old taxi driver from Zahara de los Atunes, a town near Tarifa, spent 15 days in jail earlier this year for giving a ride to three undocumented immigrants. Fellow taxi drivers went on strike to protest the government's actions. Mr. López still faces a six-year sentence if convicted of the charges against him.

June 28, 2012 update: The West Africa topic may have left Europe's headlines but the grisly topic has by no means gone away. Here are excerpts from an article in Germany's Speigel magazine, "Destination Europe: The Sahara Desert's Forgotten Refugees," by Horand Knaup reporting from Tamanrasset in southern Algeria:

Surrounded by nothing but sand and rocks, Tamanrasset, with its population of 100,000, has been a way station for emigrants from sub-Saharan Africa for two decades. At first a few dozen people passed through the city each year, then suddenly it was hundreds, and now tens of thousands. Are they refugees, migrant workers, immigrants? Definitions are fluid here. They stay for weeks or months, often even years.

Tamanrasset, marked with a red flag, is a long, long way from Europe.

But then they move on, because ultimately, they all have the same goal: Europe, the continent that draws them north like iron filings pulled toward a magnet. Estimates say only around 15 to 20 percent actually arrive there. But these refugees don't let anything stop them from trying, not barbed wire or border guards, not bandits or the reports of the many hundreds of people who drown each year trying to cross the sea. They want to escape the hardship back home, so they chase after the dreams that satellite TV has planted in their minds. …

The last residential neighborhoods at the western edge of the city give way directly to the desert. Another kilometer further out, slightly uphill from the city, is where the undocumented immigrants live. They have a few blankets, which get rolled up and stored under rocks during the day. There's some firewood and a couple of cooking pots, water bottles and a great deal of garbage. Other than that, they have no possessions beyond their own miserable living conditions.

Mar. 28, 2013 update: A news report headline at a near-random moment: "Italian coastguard intercepts more than 470 migrants." In it, we learn that the past two days' haul included eight boats, an indication that spring has sprung. Most of the boats, one with 98 passengers, one with 131, and a third with 31, were heading for Lampedusa. In addition, the Maltese authorities intercepted 90 migrants in their waters.

No governments or aid organizations provide help. Algeria doesn't want to support migrant workers. A few good-hearted nuns occasionally bring blankets, an Italian organization donates money for medications and two or three doctors at the hospital will treat patients for free. There's no aid beyond that. …

Once they've saved enough money for their onward journey, these refugees could choose to board a bus for a comfortable ride to Algiers. Instead, armed with a bit of bread, a few cans of food and a water canister, they climb aboard a truck in the back courtyard of a building, setting out at night to avoid patrols. Once outside the city limits, the driver leaves the paved road and trundles northward on dirt tracks.

The journey to Morocco costs €4,000 ($5,000), Varny says, or €6,000 including the crossing to Spain, and Nigerians have a firm hold on this line of business. Women have it easier, he says, though there's the not insignificant drawback that they have to work off their debts in Spanish brothels. …

Tamanrasset is one of the few stopovers for refugees from sub-Saharan Africa, because there aren't many options when it comes to crossing the Sahara. And since the civil war in Libya closed off that route to the Mediterranean, only two other possibilities remain. One way is to follow the western coast of Africa through Senegal and Mauritania to Morocco, then cross the sea to Spain. The other way is to try crossing the Sahara through the middle, a route that passes through Tamanrasset. …

So they find themselves blown about like drifting Saharan sand, partly because they know so little about Europe. In the best cases, they have a friend or a relative there, or at least a telephone number they can call when they arrive. But in most cases, they have and know nothing at all.

For these refugees, Europe is a secret cipher that stands for their dreams of a better life, for work and education and wealth. Europe is the promised continent they know from TV, where African soccer players can make it big, where supposedly there are jobs for everyone and always enough food, hospitals and good schools.