In a 1995 op-ed, "It's Not the Economy, Stupid," that I expanded in early 2002 as "God and Mammon: Does Poverty Cause Militant Islam?" I took issue with the widespread assumption that socio-economic distress drives Muslims to radical Islam, finding that this "is not a response to poverty or impoverishment .... The factors that cause militant Islam to decline or flourish appear to have more to do with issues of identity than with economics."

It has been gratifying to see that several studies have since confirmed this conclusion, though they tend to look more at terrorism than at militant Islam. The most recent entry is Alan B. Krueger and Jitka Maleckova in "Does Poverty Cause Terrorism? The economics and the education of suicide bombers," in the New Republic. There, they state:

That poverty is a scourge that the international aid community and industrialized countries should work to eradicate is also beyond question. There is also no doubt that terrorism is a scourge of the contemporary world. What is less clear, however, is whether poverty and low education are root causes of terrorism.

(June 24, 2002)

June 15, 2003 update: In "Seeking the Roots of Terrorism," Alan B. Krueger and Jitka Maleckov conclude more forcefully that "any connection between poverty, education, and terrorism is, at best, indirect, complicated, and probably quite weak."

Marc Sageman, author of "Understanding Terror Networks."

July 1, 2004 update: Most Arab terrorists are "well-educated, married men from middle- or upper-class families, in their mid-20s and psychologically stable"; that's how Knight Ridder Newspapers summarizes the findings of Marc Sageman, a psychiatrist formerly of the U.S. Navy and CIA, now at the University of Pennsylvania, in his forthcoming book, Understanding Terror Networks.

Oct. 1, 2003 update: Scott Atran summarizes his research, reaching similar conclusions, in Discover. In reply to the question, "what's the root cause of suicide terrorism?" he replies: "As a tactical weapon, it emerges when an ideologically devoted people find that they cannot possibly obtain their ends in a sort of fair fight, and when they know they're in a very weak position, and they have to use these kinds of extreme methods." Throughout the interview, he stresses the sanity, education, and high-status of suicide bombers.

A surprising number have graduate degrees. And they are willing to give up everything. They give up well-paying jobs, they give up their families, whom they really adore, to sacrifice themselves because they really believe that it's the only way they're going to change the world

Oct. 3, 2004 update: Marc Sageman concludes in book Understanding Terror Networks – reports the Los Angeles Times – from the study of 172 case studies of mujahidin (fighters of jihad), and that social bonds have more of a force than religion in molding extremists. One excerpt:

Most of the accused or convicted extremists Sageman studied were middle-class or wealthy rather than poor, married rather than single, educated rather than illiterate. With the exception of Persian Gulf Arabs raised mostly in devout households, many extremists became religious as young adults, Sageman found. This reinforces his view of the decisive role of the loneliness and alienation of the immigrant experience. Whether expatriate engineers studying in Germany or second-generation toughs on the edges of French cities, young Arab men find companionship and dignity in Islam. The social connection usually precedes their spiritual engagement, he says. In mosques, cafes and shared apartments, religion nurtures their common resentment of real and imagined sufferings, Sageman says.

I would argue that ideas play a more important role than Sageman allows, but the key point is that economics are next to irrelevant in the formation of terrorists.

Oct. 13, 2004 update: I have now seen the Sageman book myself and note that he finds that three quarters of his sample of Al-Qaeda members are from the upper or middle class. Moreover, he notes, "the vast majority – 90 percent – came from caring, intact families. Sixty-three percent had gone to college, as compared with the 5-6 percent that's usual for the third world. These are the best and brightest of their societies in many ways." Nor were they unemployed or isolated. "Far from having no family or job responsibilities, 73 percent were married and the vast majority had children.... Three quarters were professionals or semiprofessionals. They are engineers, architects and civil engineers, mostly scientists."

Nov. 4, 2004 update: Alberto Abadie, an associate professor of public policy at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, has found – contrary to his expectations – that terrorist violence, both international and domestic, is not related to a country's economic advancement and is related to it political freedom. He reached this conclusion in a research paper that examines the connection between terrorism and such variables as wealth, political freedom, geography, and ethnic fractionalization.

He noted two other points of interest. (1) Terrorism is less frequent in truly free and truly repressive societies. It is those in the middle, such as Iraq and Russia at present, that experience this scourge the most. "When you go from an autocratic regime and make the transition to democracy, you may expect a temporary increase in terrorism," Abadie told the Harvard Gazette.

(2) Geography matters. "Failure to eradicate terrorism in some areas of the world has often been attributed to geographic barriers, like mountainous terrain in Afghanistan or tropical jungle in Colombia." This correlation does not surprise Abadie: "Areas of difficult access offer safe haven to terrorist groups, facilitate training, and provide funding through other illegal activities like the production and trafficking of cocaine and opiates."

Jan. 26, 2005 update: The Middle East Media and Research Institute (MEMRI) published a survey of three Arab columnists today, all of whom argue that terrorists are motivated by cultural and religious factors, not poverty. The three (Muhammad Mahfouz, in the Saudi Gazette; Abdallah Rashid, in Al-Ittihad, and Abdallah Nasser al-Fawzan, in Al-Watan) cite the role of cultural and religious factors in motivating terrorism, and particularly the incitement by sheikhs who encourage young men to conduct terror operations.

August 1, 2005 update: An extremist British Muslim, Hassan Butt, rejects the economics argument in an interview, "A British jihadist." Asked if the rise of Islamic extremism among British Muslims is rooted in economic disadvantage, he replies:

I think that's a myth, pushed forward by so-called moderate Muslims. If you look at the 19 hijackers on 9/11, which one of them didn't have a degree? Muhammad Atta was an engineer [he was actually an architect and town planner] at the highest level. His Hamburg lecturer said, "I didn't have a student like him." These people are not deprived or uneducated; they are the peak of society. They've seen everything there is to see and they are rejecting it outright because there is nothing for them. Most of the people I sit with are in fact university students, they come from wealthy families. ... this myth - that the only reason these people go for Islam is because they have nothing else to do - is a lie and a fabrication. People who say that should be very careful. Even Osama himself, Sheikh Osama, came from wealth that I could never dream of and he gave it all up because it had no value to him. Who can say he came from an economically deprived condition? It's rubbish.

Jan. 6, 2006 update: Elegantly confirming Hassan Butt's view is the news that Shehzad Tanweer, a 22-year-old 7/7 suicide bomber who killed eight Londoners, left an estate worth £121,000 after loans, debts and funeral costs had been paid. The origins of his fortune are a bit of a mystery, given that he had worked part time in his family's chip shop in Beeston, Leeds.

Nov. 6, 2006 update: Claude Berrebi of Princeton University summarizes his 76-page research study, "Evidence about the Link Between Education, Poverty and Terrorism Among Palestinians," as follows:

This paper performs a statistical analysis of the determinants of participation in Hamas and PIJ terrorist activities in Israel from the late 1980's to the present, as well as a time series analysis of terrorist attacks in Israel with relation to economic conditions. The resulting evidence on the individual level suggests that both higher standards of living and higher levels of education are positively associated with participation in Hamas or PIJ. With regard to the societal economic condition, no sustainable link between terrorism and poverty and education could be found,

Dec. 6, 2006 update: Broader research by Jean-Paul Azam and Alexandra Delacroix in the Review of Development Economics, "Aid and the Delegated Fight Against Terrorism," finds "a pretty robust empirical result showing that the supply of terrorist activity by any country is positively correlated with the amount of foreign aid received by that country." Taken out of jargon, they are saying that an increase in foreign aid means an increase in terrorism.

Aug. 28, 2007 update: Alan B. Krueger, Bendenheim professor of economics and public policy at Princeton University, has turned his essay (see the June 24, 2002 entry above) into a book, What Makes a Terrorist: Economics and the Roots of Terrorism (Princeton University Press). From its introduction:

Although there is a certain surface appeal to blaming economic circumstances and lack of education for terrorist acts, the evidence is nearly unanimous in rejecting either material deprivation or inadequate education as an important cause of support for terrorism or of participation in terrorist activities. The popular explanations for terrorism—poverty, lack of education, or the catchall "they hate our way of life and freedom" —simply have no systematic empirical basis.

Sep. 7, 2007 update: Steven Stotsky of the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America shows an uncannily close relationship in "Correlating Palestinian Aid and Homicides 2000-2007" between foreign funding to the Palestinian Authority and numbers of homicides. He is cautious about drawing a causal connection from this pattern ("These statistics do not mean that foreign aid causes violence; but they do raise questions about the effectiveness of using foreign donations to promote moderation and combat terrorism") but it sure does look like giving the PA another each US$1.25 million means an additional death within the year.

Oct. 1, 2007 update: Diego Gambetta and Steffen Hertog put another nail in the poverty-made-them-do-it thesis. Here is the abstract of their impressively researched 90-page paper, "Engineers of Jihad":

We find that graduates from subjects such as science, engineering, and medicine are strongly overrepresented among Islamist movements in the Muslim world, though not among the extremist Islamic groups which have emerged in Western countries more recently. We also find that engineers alone are strongly over-represented among graduates in violent groups in both realms. This is all the more puzzling for engineers are virtually absent from left-wing violent extremists and only present rather than over-represented among right-wing extremists. We consider four hypotheses that could explain this pattern. Is the engineers' prominence among violent Islamists an accident of history amplified through network links, or do their technical skills make them attractive recruits? Do engineers have a 'mindset' that makes them a particularly good match for Islamism, or is their vigorous radicalization explained by the social conditions they endured in Islamic countries? We argue that the interaction between the last two causes is the most plausible explanation of our findings, casting a new light on the sources of Islamic extremism and grounding macro theories of radicalization in a micro-level perspective.

Sep. 10, 2009 update: More on Steffen Hertog, professor at the Institute for Political Studies in Paris, who discussed his research findings at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He noted that Islamist terrorists are generally better educated than the population as a whole, with engineers and engineering students making up about 40 percent of those involved in high-profile attacks. "There is a positive correlation between the degree of education and the level of extremism," Mr. Hertog said. Engineers made up about a third of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorists and two thirds of the Bali attack. His research will appear in a book titled, Engineers of Jihad.

By way of explanation, Marc Sageman suggested that engineering, as an especially prestigious career in the developing world, attracts "action-oriented" types. "Engineers are more action-oriented than, for example, lawyers. We don't see any lawyer getting involved in a radical extremist group."

Feb. 7, 2010 update: Eli Berman, professor of economics at the University of California, San Diego, has written a dissent to the prevailing not-economics school of thought. In a new book, Radical, Religious, and Violent: The New Economics of Terrorism (M.I.T. Press) he argues that Islamist terrorists are economically rational actors. Excerpts from an article by Devin Leonard in the New York Times

Professor Berman says that some of the most effective and resilient groups with terrorist links are in some ways economic clubs, run by "radical altruists." He puts Hamas, Hezbollah and the Taliban (the United States has tied all three to terrorism) in this category. Some of these militant soldiers of Islam may sometimes commit atrocities. But Professor Berman contends that they genuinely want to help their members. They raise money from foreign governments — or, in the case of the Taliban, by selling opium — and provide social services and jobs to adherents.

The author notes that in South Lebanon, Hezbollah operates two private hospitals and a number of schools. It collects garbage, provides water and even manages an electricity grid. He says the Taliban operate 13 "guerrilla law courts" in Afghanistan where locals can have disputes resolved.

On this basis, "radical Islamic groups extract sacrifices from their members that have economic consequences." He offers specifics:

Families are encouraged to have lots of children, and the women are less likely to get jobs and have money to spend. Professor Berman says that these organizations also prefer that their members send their children to Islamic schools, whose graduates are less likely to obtain jobs that pay them enough money to explore the market and its temptations. Indeed, he says, these are some of the ways that radical believers ensure that their followers remain loyal.

Berman draws a policy conclusion from this: "we need to do more to stop their revenue streams. He recommends that we discourage gulf states from contributing money to Hamas and cut off the Taliban's inflows of cash from illegal activities." Also, he believes the U.S. government should compete with the terrorist organizations by offering social services in Iraq and Afghanistan. "In the long run, those constructive approaches may well be cost-effective for the United States and other developed countries that are subject to international terrorism."

Comment: Berman's interpretation makes no sense to me. Indeed, it sounds like an academic version of the notorious 2002 statement by Sen. Patty Murray (Democrat of Washington State), explaining Usama bin Ladin's appeal in the Middle East and Africa: "He's been out in these countries for decades building schools, building roads, building infrastructure, building day care facilities, building health care facilities and people are extremely grateful. He's made their lives better. We have not done that."

May 23, 2011 update: Interestingly, a parallel assumption that crime increases when the economy slides also seems to be incorrect, judging by an article today, "Steady Decline in Major Crime Baffles Experts," by Richard A. Oppel Jr. Excerpts:

The number of violent crimes in the United States dropped significantly last year, to what appeared to be the lowest rate in nearly 40 years, a development that was considered puzzling partly because it ran counter to the prevailing expectation that crime would increase during a recession.

In all regions, the country appears to be safer. The odds of being murdered or robbed are now less than half of what they were in the early 1990s, when violent crime peaked in the United States. Small towns, especially, are seeing far fewer murders: In cities with populations under 10,000, the number plunged by more than 25 percent last year. ...

Criminology experts said they were surprised and impressed by the national numbers. ... "Remarkable," said James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University. ...

some experts said the figures collided with theories about correlations between crime, unemployment and the number of people in prison. Take robbery: The nation has endured a devastating economic crisis, but robberies fell 9.5 percent last year, after dropping 8 percent the year before. "Striking," said Alfred Blumstein, a professor and a criminologist at the Heinz College at Carnegie Mellon University, because it came "at a time when everyone anticipated it could be going up because of the recession."

Mar. 16, 2013 update: The Economist summarizes Clerics of the Jihad by Richard Nielsen of Harvard University. He

has examined the books, fatwas (religious rulings) and biographies of 91 modern Salafi clerics, as well as of 379 of their students and teachers. He found that the main factors behind radicalism are not poverty or the ideology of their teachers (as might be assumed) but the poor quality of their academic and educational networks. Such contacts determined the clerics' ability to get a good job as imam or teacher in state institutions. In Saudi Arabia and Egypt, where most of the 91 came from, the government has long co-opted religious institutions.

Those who failed to land a job were more likely to avow violence as a tool for political change. The figures are startling. Clerics with the best academic connections had a 2-3% chance of becoming jihadist. This rose to 50% for the badly networked.

From Nielsen's book abstract: "Clerics who are central in the network are substantially less likely to adopt Jihadi ideology than their less-networked peers."

Mar. 18, 2013 update: Sultan Mehmood, an advisor to the Dutch government on macroeconomic policy, offers an important analysis. He begins with a theoretical point: Because Gary Becker and others have established a correlation between poverty and crime, many have assumed a similar link between poverty and terrorism. He cites Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, King Abdullah of Jordan, the archbishop of Canterbury, Tony Blair, and Jessica Stern as subscribing to this view. Indeed, I add: it is well-nigh universal.

But, Mehmood notes, neither the START Global Terrorism Database nor researchers have validated such an assumption. Indeed, a recent review of the literature by Martin Gassebner and Simon Luechinger of the KOF Swiss Economic Institute, established this absence of a link:

The authors estimated 13.4 million different equations, drew on 43 different studies and 65 correlates of terrorism to conclude that higher levels of poverty and illiteracy are not associated with greater terrorism. In fact, only the lack of civil liberties and high population growth could predict high terrorism levels accurately.

Mehmood then turns to Pakistan which, he argues, has a unique importance because the death toll from terrorism there "exceeds the combined terrorism-related deaths for both Europe and North America." Hence, understanding terrorism means understanding its dynamics and causes in Pakistan. He finds several indications that the same lack of linkage between poverty and terrorism holds there:

Christine Fair from Georgetown University documents a similar phenomenon for Pakistan. By utilising data on 141 killed militants, she finds that militants in Pakistan are recruited from middle-class and well-educated families. This is further corroborated by Graeme Blair and others at Princeton University. They too find evidence of a higher support base of terrorism from those who are relatively wealthy in Pakistan. In a robust survey of 6,000 individuals across Pakistan, it is found that the poor are actually 23 times more averse to extremist violence relative to middle-class citizens.

My own work too comes to a similar conclusion. Exploiting the econometric concept of Granger causality and drawing on data from 1973-2010 in Pakistan, I document a one-way causality running from terrorism to GDP, investments and exports. The results indicated that higher incidence of terrorism reduced GDP, investments and exports. However, higher GDP, exports and investment did not reduce terrorism. The bottom line: when the economy was not doing well, terrorism did not increase and vice versa.

So, what moves individuals to adopt terrorism?

Mehmood cites Alan Krueger of Princeton University who

observes another pattern in data: a systematic relationship between political oppression and higher incidence of terrorism. He relates terrorism to voting behaviour and concludes that terrorism is a "political, not an economic phenomenon". He defends his results by arguing at length that political involvement requires some understanding of the issues and learning about those issues is a less costly endeavour for those who are better educated.

Just as the more educated are more likely to vote, similarly they are more likely to politically express themselves through terrorism. Hence, political oppression drives people towards terrorism. To understand what causes terrorism, one need not ask how much of a population is illiterate or in abject poverty. Rather one should ask who holds strong enough political views to impose them through terrorism.

It is not that most terrorists have nothing to live for. Far from it, they are the high-ability and educated political people who so vehemently believe in a cause that they are willing to die for it.

The solution to terrorism, writes Mehmood, "is not more growth but more freedom."

Comments:

(1) This conclusion comports generally with my view that terrorists are motivated by politics rather than economics. But if freedom is the key, why do Muslims living in the West disproportionately engage in terrorism? I would argue that there is no single key, that taking up terrorism results from an unquantifiable mix of personality, outlook, and circumstances beyond the reach of social scientists.

(2) Read again this phrase: "the poor are actually 23 times more averse to extremist violence relative to middle-class citizens": that decisively sums up the topic.

Apr. 4, 2013 update: The Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, N.Y. has just published a 56-page study, The Fighters of Lashkar-e-Taiba: Recruitment, Training, Deployment and Death that looks at 917 biographies of Lashkar members killed in combat. It provides important insight into the characteristics of Pakistani terrorists. Looking into their educational background, it finds:

There is a lingering belief in the policy community that Islamist terrorists are the product of low or no education or are produced in Pakistan's madrassas, despite the evolving body of work that undermines these connections in some measure. Our work on LeT continues to cast doubt upon these conventional wisdoms. As we demonstrate in the following section, LeT militants are actually rather well educated compared with Pakistani males generally.

Then, about employment, the study's authors make three points:

First, LeT militants are typically low‐income workers who come from the poor or middle‐lower classes. The top five occupations of the militants, as revealed by the data, are factory worker, farmer, tailor, electrician and laborer. This finding corroborates Mariam Abou Zahab's observations: "Although the LeT claims that the mujahidin are recruited from all social classes, most of them belong to the lower middle class . . ."

Second, the number of LeT members on whom we have this type of data and who previously served in Pakistan's armed forces is remarkably small, only 7 out of 270, or less than 3 percent.

Third, only two people in our dataset of over nine hundred biographies were associated with a religious group as a previous form of employment.

June 9, 2014 update: Jeff Burdette notes in "Rethinking the Relationship Between Poverty and Terrorism" that "a substantial amount of scholarship casts doubt on the purported nexus between poverty and terrorism," or what he calls the poverty-terrorism hypothesis. Despite this, he argues that while

Poverty does not cause terrorism, but neither is it irrelevant. Numerous empirical and anecdotal studies demonstrate that there is no direct connection between poverty and terrorism. However, poverty can still have an important, if indirect, role in contributing to an individual or group's predisposition to participate in terrorism. Poverty can help spur radicalization by reinforcing other sources of disaffection and can also increase opportunities for terrorism by hampering the ability of governments to effectively employ counterterrorism measures. ... Indeed, by contributing to radicalization and expanding opportunities for political violence, poverty still bears on terrorism in three important, if indirect, ways.

Those three ways:

- socioeconomic deprivation relative to the expectations of a group or individual can be a significant grievance. ...Notably, the economic factors by themselves are less important than their role in substantiating and reinforcing existing grievances.

- economic deprivation can also indirectly foster radicalization by producing and emphasizing status dissonance. ... unrealized expectations of success often drive radicalization by compelling young men with limited opportunities to seek status through participation in terrorism.

- poverty can contribute to terrorism by increasing opportunities for violent political action.

Burdette concludes:

a review of the literature suggests that poverty is not a direct and immediate cause of terrorism. At the same time, it can have an important, albeit indirect, role in producing political violence. Most importantly, it can promote radicalization by reinforcing other sources of disaffection or facilitate terrorism by weakening state capacity and offering greater opportunity for violent political expression.

This has policy implications:

Broad poverty reduction programs, while admirable in their own right, are unlikely to be an effective counterterror tool. On the other hand, more targeted assistance – including measures aimed at reducing discrimination against minority groups, promoting positive paths to self-esteem for potential terrorist recruits, or bolstering indigenous counterterrorism security forces – may have a more significant impact.

Apr. 3, 2015 update: Nicolai Sennels reports on a study by Marion van San of Erasmus University in Rotterdam that "Muslims are not radicalized by poverty, racism or lack of integration. Muslims are radicalized by Islam. The fact is that Islam is the only religion where its followers become more violent the more they follow their religion."

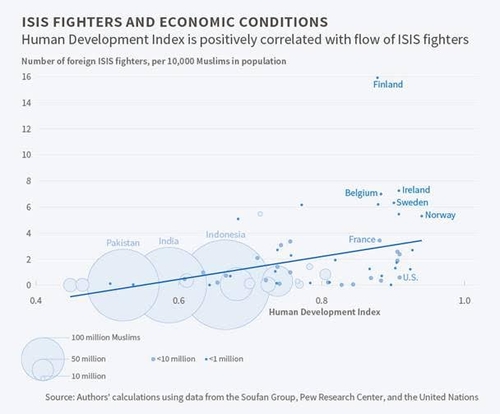

July 1, 2016 update: The World Economic Forum shows that the "Human Development Index is positively correlated with the flow of ISIS fighters to Syria.

Nov. 19, 2016 update: Giulio Meotti takes another crack at this topic at "Islamic Terrorists not Poor and Illiterate, but Rich and Educated."

Jan. 2, 2017 update: Khaled Montaser, an Egyptian intellectual argues, in paraphrase, that Islamism "does not stem from poverty or ignorance" but from an interpretation of religion that conflicts with modernity."

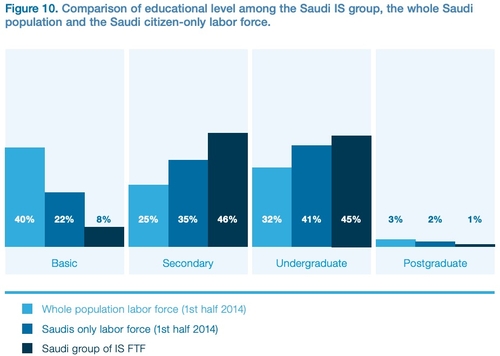

socioeconomic factors hold limited explanatory value when it comes to the radicalisation of this group of Saudis, since the majority of them were neither social outcasts nor educational underachievers.

The following chart reveals how would-be ISIS members are more educated than Saudi workers as a whole (FTF stands for "foreign terrorist fighter").

July 2, 2020 update: So many years later, wealthy jihadis still manage to surprise. Here is Samanth Subramanian writing the New York Times on the affluent Ibrahim brothers of Sri Lanka who joined others in a suicide bombing rampage in April 2019, killing a total of 269 people:

Of all the bombers, these two young men proved the most baffling to other Sri Lankans. There have always been well-off terrorists, even wealthy ones. Still, when new examples emerge, they force us to re-examine a tenet of modern life: our belief that security and economic comforts are the rudiments of a peaceful community, and that people turn against strangers only when they face some material peril or privation. Most of us associate violence with desperation. What did the Ibrahim brothers have to be desperate about?