Ever since the French government ceded the Alexandretta province of Syria to Turkey in 1939, its control by Ankara has been a sore, obstructing the two countries' relations and at times exacerbating crises between them, most recently in 1998.

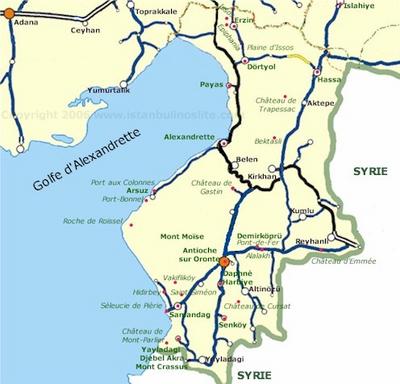

Hatay, a province of Turkey since 1939. Alexandretta (or Iskanderun) is its largest city. |

The question asked by Channel 2's analyst for Arab affairs, Ehud Ya'ari, brought a satisfied smile to the face of Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom at the joint press conference held last Tuesday in Jerusalem with Turkish Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul. Ya'ari asked the most interesting question at the press conference, which touched on the territorial conflict between Syria and Turkey. "Can Syria's recognition last month of full Turkish sovereignty over the Hatay province be seen as a precedent for the case of the Golan Heights?" Ya'ari asked.

Everyone waited suspense fully for an answer from Gul, who immediately perceived a trap. He answered with diplomatic finesse, without batting an eyelid: "The two cases are not similar, there is no territorial disagreement between Turkey and Syria, and in the second case, the United Nations determined that the territory is occupied."

The question illustrates the way in which Turkey's relations with Syria resemble Israeli-Syrian relations. On the territorial level, there is a long-standing conflict between the two countries, which was finally resolved last month, away from the eyes of the media. The conflict involved a region known as the Hatay province in Turkey and Alexandretta in Syria. Conquered in 1938 by the Turkish army, the Turks view it as an inseparable part of their country. The Syrians view it as a part of their homeland that was torn away with the consent of the French during the Mandate period, before the Syrians achieved independence. The Syrians point to the Arab residents of the region to bolster their claim.

Ever since Syrian independence in 1946, the area has been a source of constant tension. Until last month. Turkey and Syria spent a year and a half preparing a free-trade agreement between the two countries. Two Syrian prime ministers and the president - Mohammed Mustafa Mero, Naji al-Otari and Bashar Assad - visited Ankara. Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan paid a return visit last month and finally signed an agreement in Damascus.

Even more surprisingly, this Ha'aretz article was cited today as a source of information on the agreement by the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet, implying that the Turkish press knew nothing of this major accord, apparently signed on December 22.

Looking back on the coverage of that summit meeting, one finds just hints of such a deal. Here is Burak Akıncı's account for Agence France-Presse, dated December 22 and titled "Turkey, Syria sign free-trade accord amid warming ties on Erdogan visit."

Former foes Turkey and Syria signed a free-trade accord and said they had agreed to put their differences behind them during a visit Wednesday by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Erdogan, at the start of a two-day mission, and his Syrian counterpart Mohammed Naji Otri signed the deal, which had been under negotiation for several years. …

A Turkish diplomatic source said Damascus lifted its reservations to signing the trade deal "after a certain accord" was reached on Turkey's sovereignty in the southern province of Hatay, formerly Alexandretta, on which Syria had claims.

Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Syrian president Bashshar al-Asad, getting along. |

Comment: If the Syrians really have abandoned this claim, it was foreshadowed already four years ago. Here is Syrian Foreign Minister Faruq al-Shara, quoted in an Agence France-Presse report from February 5, 2001 (not online):

Asked about Damascus' claims over the southern Turkish province of Hatay, which is often shown as Syrian territory on Syrian maps, Shara said that "maybe several years" were needed to settle the problem. "Issues that seem sensitive today, could be easily resolved in the future when the bilateral climate reaches a level at which they will not pose difficulties," the Syrian minister said. "It is wrong to give priorities to such issues now becuase this could harm cooperation in other fields ... In the end they will be resolved, but we should not push more than we have to."

(January 10, 2005)

Jan. 24, 2005 update: Ehud Ya'ari, cited above, has fleshed out the picture in his Jerusalem Report column dated today, "Syrian Overture" (not online):

For years I've made it a rule to read every article that political columnist Rosanna Boumunsef writes in An-Nahar, Lebanon's most important daily. She knows what she's talking about and writes with precision.

So too with her column of December 28, following the visit of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to Syria. She quotes Lebanese Druse leader Walid Jumblatt, who of late has become the most vocal spokesman for opponents of Syrian rule in his country: "Syria has gotten over its Alexandretta complex," Jumblatt asserted, "and agreed to having Europe on its border." In other words, Syria has given up its 65-year-old claim to the sanjak (province) of Alexandretta (Iskanderun) on the Mediterranean coast, realizing that with Turkey due to join the European Union, there is no chance whatsoever of returning the province to Arab rule.

Alexandretta was given up by Syria's mandatory ruler, France, in 1939 and annexed by Turkey, which renamed the province Hatay. Turkish settlement in the region totally changed the demographic balance, reducing the relative size of the Arab minority. A year ago Syrian leader Bashar al-Asad visited Ankara for the first time, and he carefully avoided saying a word about the contested territory. Since then there's been a rapid rapprochement between the two countries, which as recently as 1998 were on the verge of war because of Syria's support for the Kurdish rebellion led by the PKK. Recently, when Erdogan visited Damascus in turn, an agreement was signed on jointly building a dam on the Orontes River on the border between Alexandretta and Syria - putting an official seal on Syria's acceptance of the loss of the sanjak.

Boumunsef quotes Asad as saying in private conversations with several of his guests that he is proud of his success at establishing warm ties with Turkey "despite the sharp territorial dispute." Asad added that "in this framework, Syria can reach peace with Israel as well." What did he mean by that? It's not clear, but Boumunsef cautiously asks, "Is the meaning of these statements that flexibility is possible in dealing with other issues, similar to his pragmatic approach to Alexandretta?"

That is: Could it be that one day Syria will deal with the Golan Heights as it is now dealing with Alexandretta?

Let's stress: Syria has not signed on to any concession concerning Alexandretta. In principle, it maintains its claim to sovereignty there. But one official commentator, Imad Shu'eibi, head of the Center for Strategic Studies in Damascus, has made clear that in fact it's been decided to "put off for coming generations" the dream of Syrian Alexandretta, and to not let the dispute prevent cooperation in other areas.

The Syrians have a very hard time explaining in public their surrender to the Turks. They are also signaling that the Golan is different. Foreign Minister Farouk Al-Shara has even made a point of correcting the impression that Asad is ready for negotiations "without preconditions," and has explained that insisting on a return to the June 4, 1967 lines is not a "condition" but a "legitimate necessity."

But one cannot avoid concluding from the Alexandretta business that Syria does not regard its borders as eternally sacred. And not only has it accepted the loss of Alexandretta, but in a border agreement signed last month with Jordan, Damascus adopted another principle: Demography can result in border corrections. Syria got Jordan's assent to annexing land along the Yarmuk River where Syrian peasants settled after the Syrian invasion of Jordan in Black September, 1970, and in exchange gave up land to Jordan in other areas.

Asad's pragmatic flexibility on borders may indicate that wider strategic concerns are getting preference over the old slogans about holding on to "every grain of sand" and the oaths never to forget "usurped" land. So there is reason to see whether the young president is willing to consider cautiously a change in Syria's stance toward Israel without demanding that withdrawal from the Golan be the first, immediate, topic on the agenda.

Ya'ari then goes on the consider the implications of the the Hatay recognition for the Golan Heights and Israel.

May 28, 2005 update: In a news item on a Syrian missile that malfunctioned and exploded in southern Hatay, Agence France-Presse gives a little background on Hatay: Syria and Turkey, it writes, "share a long border, and Hatay, which is claimed by Syria, is at its western end." Reiterating this point, AFP notes that, "Despite the improved ties between the two countries, two sticking points remain: the waters of the Euphrates River, which has its source in Turkey, and the status of Hatay."

Comment: Either Agence France-Presse has forgotten its own reporting (see its December 22, 2004 coverage from Damascus, quoted above) or the Syrians still are claiming Hatay. Which is it?

July 19, 2006 update: For a complementary entry to this one, see "'Greater Syria' in the News."

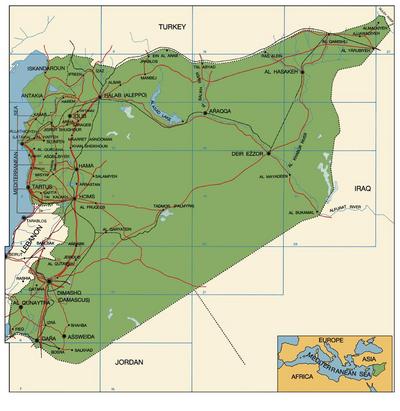

Dec. 22, 2006 update: Two years after the signing of this accord, the Syrian tourism ministry still shows a map that claims Hatay as an integral part of the Syrian Arab Republic.

Map on the Syrian Ministry of Tourism website. (This identical map appears whether one uses the English, French, or Arabic versions of the website.) |

Comment: Is Damascus playing the same game with Ankara that the Arabs do all the time with Jerusalem, that is, sign an agreement and then ignore it?

July 22, 2008 update: In a separate but related development, it appears Damascus will recognize Lebanon as a separate country.

Dec. 20, 2008 update: Four years after the supposed signing, Emmanuel Navon writes in a fine article, "Withdrawing from the Golan talks" that "Syria did not abandon its claims over Hatay, but it did abandon its demand for a return of the province to its sovereignty as a condition for ending hostilities."

Dec. 10, 2010 update: The website of Syria's rubbers-stamp parliament shows a map of Syria that includes Hatay.

Syria includes Hatay in this map on the website of Syria's parliament. |

June 24, 2011 update: The Syrian intifada that began in late January and continues unabated has badly damaged relations with Ankara, with some 11,000 Syrian refugees having crossed the border, tensions between the governments, and even the massing of troops. Hugh Eakin suggests a Hatay angle on these developments in "Will Syria's Revolt Disrupt the Turkish Borderlands?" He notes that, "With impressive speed, Turkey's Red Crescent has launched a large-scale humanitarian effort to provide a safe haven for victims of Assad's horrific crackdown," but then notes a puzzle:

while journalists seek to interview those who have fled, they have also had to confront a surprisingly recalcitrant Turkish government: for more than a week after the refugees arrived, access to the camps where they are being housed was denied; and Turkey has until now refused support from international humanitarian agencies to deal with the crisis. Still more puzzling, some Syrians who had taken refuge with expatriated relatives have also been moved to the camps where contact with their kin is difficult.

Eakin then proposes an answer: the ever-festering Hatay issue. He provides some local color on the province, then notes that

there has already been at least one protest in the Turkish border town of Samandağ by Turkish Alevis who are against allowing in (mostly Sunni) Syrian refugees to Turkey. With hundreds of Syrians crossing each day–and growing reports of Alawite-Sunni violence in Syria's northwest—such opposition in Hatay's border villages, several of which have concentrations of Alevis, could gain strength.

The Turkish government, he suggests,

may find reasons to be insecure in the not quite resolved legacy of the 1930s. … For Syria, the loss of Alexandretta is viewed as a dirty deal between the Turks and the French. Syrian officials have likened it for decades to the Golan Heights—territory that was taken away from Syria and should be reclaimed.

Paradoxically, one of Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan's foreign policy initiatives in the early 2000s was to quietly bring this dispute to an end, in part, it appears by proffering enhanced trade with and support for Syria—including, not least, an attempt to help mediate with Israel that other border dispute, the Golan. According to some reports, an unofficial deal was reached in the mid-2000s, whereby Syria would drop its claim to Hatay for the foreseeable future in exchange for getting a free trade agreement and water rights from Turkey, though it was never formally acknowledged by either side.

Now that Syrian forces are moving close to the border, reportedly cutting off the escape route for refugees, that rapprochement seems from a different era. And with the prospect of a possible military response by Turkey in the event of a further escalation across the border, it may be increasingly difficult to ignore Hatay's complicated history.

Comment: I agree with Eakin: If gloves are off between the two governments, the papered-over solutions of 2005 will prove insufficent and the Hatay issue returns with a vengeance.

Dec. 19, 2012 update: Eleven years after its publication, I have just become aware of Yücel Güçlü's important 368-page study, The Question of the Sanjak of Alexandretta: A Study in Turkish-French-Syrian Relations (Ankara: Turkish Historical Society Printing House, 2001).

Apr. 16, 2013 update: Turkish patronage of Syria's rebels means that they recognize Turkey's control of Hatay, Raja Abdulrahim reports for the Los Angeles Times:

In newly printed textbooks at dozens of Syrian refugee schools, a small piece of Middle East geography has been amended. Seventy-five years ago, Turkey annexed the northern Syrian territory of Hatay against the will of Syria, but maps in Syrian schoolbooks during the lengthy reign of the Assad family have continued to include Hatay inside Syria's borders. The maps in the new schoolbooks show Hatay in Turkey, one of a number of political changes made by the Syrian opposition group that published the books.