In an article published today, "Five Years of Campus Watch," I refer to the fact that professors often enjoy the unusual privilege of going through their careers without facing criticism. "Students must suppress their views to protect their careers; peers are reluctant to criticize each other publicly, lest they suffer this in turn; and the outside world lacks the competence to judge arcane scholarship. As a result, academics enjoy a perhaps unique absence of scrutiny."

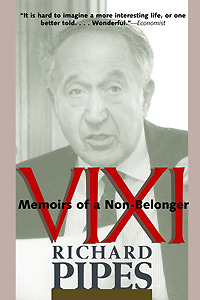

"Vixi" by Richard Pipes. |

Academic life is not all sweetness and light. Scholars are psychologically less secure than most people: by and large, once they pass the threshold of middle age they strike me as becoming restless. A businessman knows he is successful when he makes money; a politician, when he wins elections; an athlete, when he is first in sporting contests; a popular writer, when he produces best-sellers. But a scholar has no such fixed criteria by which to judge success, and as a consequence he lives in a state of permanent uncertainty which grows more oppressive with age as ambitious younger scholars elbow themselves to the fore and dismiss his work as outdated.

His principal criterion of success is approval of peers. This means that he must cultivate them, which makes for conformity and "group think." Scholars are expected to cite one another approvingly, attend conferences, edit and contribute to collective symposia. Professional associations are designed to promote these objectives. Those who do not play by the rules or significantly depart from the consensus risk ostracism. A classic example of such ostracism is the treatment meted out to one of the outstanding economists and social theorists of the past century, Frederick von Hayek, whose uncompromising condemnation of economic planning and socialism caused him to be banished from the profession. He lived long enough to see his views prevail and his reputation vindicated by a Nobel Prize, but not everyone in this situation is as fortunate. Such behavior, observed also in animal communities, strengthens group cohesion and enhances the sense of security of its individual members, but it inhibits creativity.

What particularly disenchanted me about many academics was [the way they treated] a professorship not as a sacred trust but as a sinecure, much like the run-of-the-mill Protestant ministers in eighteenth- or nineteenth-century England who did not even pretend to believe. The typical academic, having completed and published his doctoral dissertation, will establish himself as an authority on the subject of his dissertation and for the remainder of his life write and teach on the same or closely related topics. The profession welcomes this kind of "expertise" and resents anyone who attempts to take a broader view of the field because by so doing, he encroaches on its members' turf. Nonmonographic, general histories are dismissed as "popular" and allegedly riddled with errors – doubly so if they do not give adequate credit to the hordes who labor in the fields.

(September 20, 2007)

Dec. 16, 2008 update: The above situation is premised on the tenure system, whereby a professor is basically employed for life. But Mark Baulerlein, professor of English at Emory University, author of The Dumbest Generation, and formerly the director of research and analysis at the National Endowment for the Arts, argues in "Is Tenure Doomed?" that this system "has been deteriorating for years."

Administrations haven't directly taken it away. They simply let tenured professors retire and didn't give departments tenured or tenure-track replacement lines. Or, in responding to rising enrollments, they hired more part-time faculty than full-time faculty to fill classrooms. Indeed, according to the U.S. Department of Education, the portions of tenured and tenure-track faculty in the American professorate nose-dived in the last 30 years.

And according to a recent report by the American Federation of Teachers, "contingent faculty members teach 49 percent" all undergraduate courses (Reversing Course: The Troubled State of Academic Staffing and a Path Forward, i). The proportion doesn't include graduate student teachers, either, those doctoral candidates picking up courses as part of their training, which AFT estimates at 16-32 percent of the courses offered. That means tenured and tenure-track faculty handle only one-third to one-quarter of the undergraduate teaching load.

There are good practical reasons for this shift:

From a financial standpoint, tenure looks like a positive hindrance. Consider the relative costs as calculated by AFT. In 2003-04, part-time or adjunct teachers earned about $2,800 per course, while full-timers earned $11,000 per course. Add in the benefits full-timers receive (pension, health care) and the discrepancy widens. Administrators can't resist the temptation cut costs by hiring adjuncts. Mindful department chairs defy it, warning that the retirement of a senior colleague must be replaced with a tenure-track line or else the department will slip in academic prestige. But when the dean determines that immediate instructional needs of the college outweigh research needs, the decision is easy.

Comment: Higher education increasingly appears ripe for major changes.

July 4, 2010 update: Good news – tenure is evaporating from U.S. higher education, according to a report on a forthcoming report from the U.S. Department of Education with the dull title, "Employees in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2009." The Chronicle of Higher Education reports:

Over just three decades, the proportion of college instructors who are tenured or on the tenure track plummeted: from 57 percent in 1975 to 31 percent in 2007. The new report is expected to show that that proportion fell even further in 2009. If you add graduate teaching assistants to the mix, those with some kind of tenure status represent a mere quarter of all instructors. ...

The prominent shift in the makeup of the professoriate didn't occur overnight. It happened gradually, without any public endorsement or stated plan, as the byproduct of other concerns—primarily budget shortfalls and administrators' interest in gaining flexibility. Now, in whole swaths of higher education, including at many community colleges and at for-profit institutions, tenure is a completely foreign concept. And it is waning at many regional state universities and at less-elite liberal-arts colleges, as well. ...

higher-education watchers don't hold out much hope that the numbers on tenure will turn around. "In the end, these are financial decisions, and they are very hard to reverse," says Frank J. Donoghue, an associate professor of English at Ohio State University who writes about the professoriate.

Aug. 28, 2011 update: Mark Bauerlein provides some figures on "The Incredible Shrinking Tenure": In 2009, teachers at four-year colleges broke down as follows:

Tenure, full-time 25 percent

Tenure-track, full-time 11 percent

Non-tenure-track, full time 15 percent

Part-time 25 percent

Graduate assistants 25 percent

Note that tenure and tenure-track positions together amount to just over 1/3 of the teaching staff.

A second chart reveals the growth in numbers of teachers by tenure status trends over the previous decade. Numbers went up in every category but growth rates differed substantially:

Tenure, full-time 7 percent

Tenure-track, full-time 20 percent

Non-tenure-track, full time 56 percent

Part-time 49 percent

Graduate assistants 47 percent

Bauerlein sketches out what he calls not "abolition of tenure, just the reduction of it, slowly but steadily, with no real forces of resistance to stop it:

Because non-tenured instructors are so much cheaper than tenured and tenure-track instructors, the discrepancy is unlikely to change. And administrators can continue it in a process that is more or less painless to the most powerful instructors—those with tenure. If a full professor retires and the dean offers the department only a lecturer as replacement, are the other 50- and 60-year-old eminences going to protest? Unlikely, as long as their working conditions aren't affected. After all, lecturers, adjuncts, and graduate assistants make their lives easier.

June 21, 2013 update: The journal Academic Questions devotes its summer 2013 issue to the scholarly and political implications of peer reviewing. Robert Weissberg, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, explains in "The Hidden Costs of Journal Peer Review" how the opaque process of peer-reviewing articles and books stultifies debate:

The upshot of potential irresponsibly is for those submitting articles for review to play it very, very safe. The odds are against you in any case (top journals reject nearly everything), but an author should not create even more obstacles by angering anonymous reviewers or the editor. A wise and commonplace strategy would be to stay safely within the confines of accepted wisdom and use ample amounts of professional jargon to indicate familiarity with prevailing professional norms. Better to publish innocuous second-rate stuff in a first-rate peer-reviewed journal than to try to hit a scholarly home run and suffer rejection.

Academic Questions, Summer 2013 issue.

One can also up the odds of acceptance by heaping lavish praise on potential reviewers (however undeserved) while copiously citing friends who can be counted on to say "publish" if the submission comes their way. (These friends have probably read drafts, so the author will be known to them.)

Most important, in all instances avoid trouble by steering clear of anything even slightly "controversial." Don't kid yourself about speaking truth to power. If you are writing about urban politics and the prevailing orthodoxy insists that black electoral control has been a boon for African Americans in Detroit, don't disagree. You can never win an argument with an anonymous reviewer. Journal submissions are not evidence-based debates or marketplaces of ideas—once the essay is in editorial hands, you have no voice in the outcome, no matter how biased or wrong-headed.

The upshot of avoiding trouble is that whole areas of scholarship become dead zones where only the politically ultra-orthodox can survive. This is most obvious in anything having to do with "the groups"—African American studies, women's studies, Hispanic studies, queer studies, or any other subfield populated by clearly identifiable ideologues.

Even the choice of explanatory factors can lead to papers being DOA regardless of subject matter. Good luck to scholars who employ cognitive ability as measured by IQ when examining economic development or civil violence. How about submitting a paper that meticulously demonstrates that lack of impulse control explains poverty? Actually, when all these off-limits fields and subfields are added up, little remains open to anybody willing to challenge the bien-pensant crowd.

Feb. 1, 2023 update: Jacques Berlinerblau, a professor at Georgetown University and an opinion columnist for MSNBC, writes despairingly about the disappearance of tenure and, interestingly, blames the phenomenon on Ph.D.s who failed to get academic positions and went instead into academic administration.

A number of upper admins were hired to manage — some might say "rule" — the faculty. Some of those who accepted this task were scholars themselves. A novel hybrid creature, the everlasting tenured admin, was sparked to life. No three-year stint as vice dean and back to teaching freshman composition, for this guy! He was in it for the long haul.

The significance of this development is underappreciated. The decisions which ravaged the future for coming generations of Ph.D.s were made not just by consultants and suits, but by those with Ph.D.s and likely a few peer-reviewed publications. This was scholar-on-scholar violence.