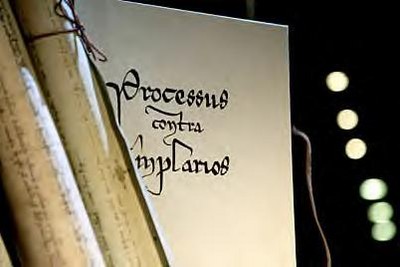

In a sensational bit of sleuthing, Barbara Frale, a medievalist at the Vatican's Secret Archives, stumbled in 2001 on Processus Contra Templarios, a compilation of original documents dating from 1307-12 on the French trial of the Knights Templar and the Vatican's response.

Here is some background on of this longest lived of all "secret societies" from my book, Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes, and Where It Comes From (Free Press, 1997), pp. 57-59, to explain why this piece of medieval news still matters intensely to some people today:

Early in 1119, a French nobleman named Hugues de Payns and nine of his companions dedicated themselves to protect Christian pilgrims on their way to and from Jerusalem, solemnizing this oath by adopting the monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The group adhered to a rule not much different from that of other monastic orders, with the exception of provisions that permitted them to make war. Theirs was a new, remarkable, and confusing development that merged two utterly different callings: the clergy (absolutely forbidden to engage in conflict) and the soldiery (which did so incessantly). A group of soldiers, renowned for their anarchism and their devotion to plunder and women, had become soldiers for Christ. In effecting this combination, they "invented an absolutely novel figure, that of the monk-knight." This radical notion turned out to be both powerful and threatening.

The king of Jerusalem welcomed the help provided by Payns and his companions; symbolic of this esteem, he installed them on the holiest spot in Jerusalem, the Temple Mount, where they lived in Al-Aqsa Mosque. The group came to be known as the Military Order of Poor Knights of the Temple of Solomon, or Templars for short. The Templars also won the fervent backing of Bernard of Clairvaux, an immensely influential cleric, and through him, the sponsorship of popes and noblemen as well as nearly universal acclaim in Catholic Europe. Their model inspired the founding of other Christian military orders, including the Knights Hospitallers of St. John and the Teutonic Knights.

As men engaged in fighting, always an expensive activity, the Templars had a constant need of funds that made them different from other monastic orders. Combined with their far-flung military power and their reputation for probity, this spurred the Templars to offer proto-banking practices at a time when deposit banking did not yet exist. Before long, they held vast sums in deposit; for example, they became bankers to most of the French royal family. Combined with their noble patronage, this occupation made the Templars very wealthy. But banking practices also made them morally suspect, for such financial activities transgressed deeply held feudal norms and were seen as contradicting their professed piety.

Another problem arose when Acre, the last Crusader stronghold, fell in 1291. The Templars had so active and prominent a role in the Crusaders' wars that their prestige, more than that of any other order, depended on the situation in the East, and the fall of Acre caused their reputation to suffer. The failure of these fighting monks to hold the Holy Land from the Muslims, when combined with their secrecy, great wealth, and arrogance, fueled resentment of their power as well as rumors about their having hidden goals.

In 1307, as the Templars were planning yet another Crusade to return to Palestine, this resentment boiled over. King Philip IV of France struck against the order, seizing its members and confiscating their wealth. After a seven-year legal process in which the prosecutors relied heavily on torture, humiliation, and other psychological inducements to get the answers they sought, the Templars were finally found guilty of apostasy. In a great show of power, Philip had their grand master, Jacques de Molay, burned at the stake [in 1314]. Rulers everywhere in Europe but Iberia followed Philip's example and succeeded in completely suppressing the order. Centuries later it is clear that, however powerful and perhaps even out of control the Templars were, they never engaged in heresy nor posed a threat to the existing order.

Oh, and the arrests took place on October 13, 1307, exactly 700 years ago tomorrow. So much for history, now as to why all this still captivates conspiracy theorists:

Several features about the Knights Templar make them enduringly enigmatic. They had a conspiratorial air about them; for example, at the initiation ceremony, a candidate was told that "of our Order you only see the surface which is the outside," implying that something very secret took place behind closed doors. At the end of the initiation, each knight kissed the adept on the mouth, an act with obvious homosexual overtones. Further, the brutal suppression by Philip had an air of mystery about it. To this day, "the accusations of heresy are unproven and the evidence for internal decline impossible to assess."

Together, the spectacular rise, great power, and grisly end of the Templars turned them into a permanent feature of European conspiracy theories. The Knights Templar stand out as the original and most omnipresent of secret societies. Looking back, even those conspiratorial groups in the hoary mists of antiquity take definite shape only with the Knights Templar. Looking ahead, virtually all secret societies in recent centuries are seen as deriving from them: "The Templars have something to do with everything." Occultists imbued them with magical powers, and Enlightenment rationalists turned them into an anti-Christian conspiracy. In addition, many romantics fell under the spell of the Templars' sensational tale, wasting untold hours in search of their idols, secret rule, and hidden treasures, speculations that amount to nothing more than "a wild fantasy" of "mystagogy and obfuscation."

"Processus Contra Templarios" in replica, 799 copies available at €5,900 each. |

The Vatican Secret Archives, in collaboration with the Scrinium cultural foundation, is publishing 799 copies of a replica of the document, to be officially presented on October 25. The replicas cost €5,900 each because they come "in a soft leather case that includes a large-format book including scholarly commentary, reproductions of original parchments in Latin, and—to tantalize Templar buffs—replicas of the wax seals used by 14th-century Inquisitors. One parchment measuring about half a meter wide by some two meters long is so detailed that it includes reproductions of stains and imperfections seen on the originals."

According to Reuters, the Knights Templar will be "partly rehabilitated" by these documents. In particular, the so-called Chinon Parchment

contains phrases in which Pope Clement V absolves the Templars of charges of heresy, which had been the backbone of King Philip's attempts to eliminate them. … Frale said Pope Clement was convinced that while the Templars had committed some grave sins, they were not heretics. Their initiation ceremony is believed to have included spitting on the cross, but Frale said they justified this as a ritual of obedience in preparation for possible capture by Muslims. They were also said to have practiced sodomy. "Simply put, the pope recognized that they were not heretics but guilty of many other minor crimes—such as abuses, violence and sinful acts within the order," she said. "But that is not the same as heresy."

Despite his conviction that the Templars were not guilty of heresy, in 1312 Pope Clement ordered the Templars disbanded for what Frale called "the good of the Church" following his repeated clashes with the French king. Frale depicted the trials against the Templars between 1307 and 1312 as a battle of political wills between Clement and Philip, and said the document means Clement's position has to be reappraised by historians. "This will allow anyone to see what is actually in documents like these and deflate legends that are in vogue these days," she said.

But deflating legends will not be easy. One conspiracy theorist, Vortex, reacted to these developments with doubts that are probably typical of the mentality: "I wonder just how much has been censored by the Holy Sea [sic], or tucked back away not to see the light of day that runs against some teachings or puts a 'guilty' light on Rome." And an organization called Ordo Supremus Militaris Templi Hierosolymitani claims "more than 5,000 Knights and Dames of the Knights Templar worldwide," so in some fashion, the Templars live on. (October 12, 2007)