Most nuclear physicists these days lead a fairly humdrum existence; but not if they live in Iraq. Khidhir Hamza, born in that country in 1939, and fascinated by electricity from a young age, attended Baghdad University before receiving a master's degree from MIT and a Ph.D. in theoretical nuclear physics from Florida State University in 1968. After beginning his teaching career at an American college, he was summoned back to teach in Iraq in order to pay off his educational debts.

Most nuclear physicists these days lead a fairly humdrum existence; but not if they live in Iraq. Khidhir Hamza, born in that country in 1939, and fascinated by electricity from a young age, attended Baghdad University before receiving a master's degree from MIT and a Ph.D. in theoretical nuclear physics from Florida State University in 1968. After beginning his teaching career at an American college, he was summoned back to teach in Iraq in order to pay off his educational debts.

Invited to join the nascent Iraqi nuclear effort in 1972, Hamza did so with some enthusiasm, considering it a wonderful professional challenge. At the time, he did not rate very highly the prospects of a bomb actually being built; and, he reasoned, even if that should somehow come to pass, surely the weapon would be used as a negotiating chip vis-à-vis Israel and nothing more. "The mission," he writes here, was in any case "breathtaking: build a nuclear bomb from scratch, starting on a dining-room table."

Hamza soon began a long march through the bureaucracy, manifesting, in addition to his talents as a scientist and scholar, a finely tuned aptitude for staying out of trouble. Of Iraq's three original nuclear scientists, he alone in those early years managed to escape the capricious wrath of Saddam Hussein, who was still making his way toward the absolute power he would gain in 1979. By 1981, Hamza was working directly for Saddam; by 1987, he had reached the position of director general of Iraq's nuclear-weapons program.

His new status inevitably brought head-turning benefits: a high salary, fancy cars, travel to the West, even a residence within the presidential compound. "All that loot was softening me up, I don't deny it," Hamza writes in Saddam's Bombmaker. "But it was the project itself, the enormity of the task, and the pure, scientific challenge of cracking the atomic code, that excited me more."

Even as he rose through the ranks, however, Hamza worried about surviving his contact with Saddam. With time, indeed, his absorbing intellectual venture turned into a descent into a kind of Stalinist hell. Not only did colleagues begin to turn up murdered, but it was becoming increasingly clear that Saddam Hussein actually intended to use the bombs Hamza was working on developing. Though himself untouched by torture or other barbarities, and still benefiting from occasional trips abroad ("just walking down Broadway [in New York] and breathing free air was invigorating"), Saddam's chief nuclear scientist saw enough to want out.

In 1987, he began trying to extricate himself not just from building the bomb but from Iraq. He achieved the first goal three years later, leaving active administration and returning to the classroom. In 1994, although feeling "too old, too comfortable, [and] too scared," he managed to accomplish the second. After a particularly stressful year in limbo, mostly in Libya, he was finally joined by his wife and three sons. The family settled quietly in the United States, and Hamza underwent a comprehensive debriefing.

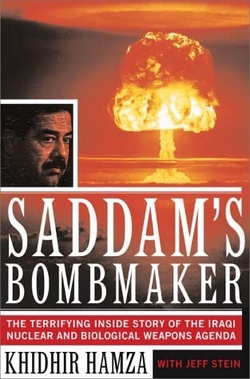

Today, rightly fearful that Saddam wants him dead, Hamza lives in a semi-underground manner, partly by means of tactics taught him many years earlier for evading Israeli agents. Although he has been well-known in the circles of Iraq-watchers, Saddam's Bombmaker represents his most sustained effort to go public. A memoir, and a compellingly written one (thanks in large part to his co-writer Jeff Stein), it also contains important and reliable information, from a credible author, on two quite distinct topics of current interest: the inner workings of the Iraqi nuclear-weapons project, and life at the highest levels of the Iraqi regime. It is hard to say which is scarier.

Hamza establishes that Iraq's nuclear-weapons program has followed two principal stages. The initial one, lasting from 1972 until 1981, involved a relatively small investment of money and depended heavily on imported (mostly French) technology. The second one began with the Israeli destruction of Iraq's Osirak reactor in June 1981, an event that spurred the regime to rethink and radically expand its whole program. Hamza thus agrees with Shimon Peres's controversial assessment that, from Israel's point of view, the attack on Osirak was a mistake.

After 1981, in any event, and proceeding more or less indigenously, the Iraqis devoted 25 times more resources than previously to the bomb. Their headlong effort culminated in 1990 with (in Hamza's words) "a crude, one-and-a-half ton nuclear device"-not quite yet a bomb, and far too large to be carried on a missile, but an important step along the way.

As Hamza documents, the outside world was slow to recognize the change from stage one to stage two, and this had important consequences in the aftermath of the Gulf war. Not realizing how much the Iraqis themselves had accomplished, those leading the disarmament efforts after 1991 focused not on Iraq's capabilities-both material and intellectual-but on actual weapons. Destroying those weapons would have made sense had Saddam's regime depended on imported material and talent; as things stood, it was a nearly futile undertaking, for they could always be rebuilt. Only in mid-1995, when the U.S. government simultaneously debriefed Hamza and his former boss (and Saddam's son-in-law) Hussein Kamil, did it realize the true scope of Iraq's program.

According to Hamza, it was his identification of the 25 or so key nuclear scientists in Iraq, and where they could be found, that drove Saddam to close down international inspections in mid-1998. Today, Hamza estimated at a recent presentation in New York, Iraq is "undoubtedly on the precipice of nuclear power," and will have "between three to five nuclear weapons by 2005." What it will do then is a nice question, the answer to which depends in part on circumstances but in much larger part on the designs, and the character, of its president.

This is where Hamza's second topic comes in: Saddam Hussein's personality and the nature of the regime he has built up. One thing we learn from this book is that, in common with other despots of recent times, he is a man who sees danger truly everywhere. Thus, he has "a terrible fear, perhaps paranoia, about germs"; any visitor to a room where he is present must undergo an eye, ear, and mouth inspection before entering. Stalin, one recalls, had his regime's top figures sample his food; Mao suspected his swimming pool was poisoned, and refused medical care at the hands of doctors he was sure would do him in.

Saddam also has a taste for virgins - who, among other desirable qualities, are thought to be less disease-prone. In one anecdote related by Hamza, a young woman who pleaded with the president for aid after the death of her father ended up losing her virginity after having been given a beauty makeover and left naked on a bed to await his (wordless) pleasure. Although she was let go with an envelope of money, other "young, beautiful, and flirtatious" women who have serviced Saddam find themselves retained as virtual slaves to clean the apartments of his nomenklatura. Or else not retained at all; Hamza tells of one who was discovered in a bathtub with her throat slit.

Hamza likewise confirms the picture of Saddam as someone "incalculably cruel," a man whose taste for personal brutality is exercised frequently and unpredictably. Once, listening to suggestions he considered defeatist, the president pulled out a revolver and simply shot dead the military officer making them; at a meeting with his top leadership, he abruptly had a general whisked off to the torture cells; a guard who incautiously confided the president's whereabouts - to a personal friend of the president - was shot on the spot for indiscretion. Hamza's phrase for Saddam is "an expertly tailored, well-barbered gangster"; the description fits. To the woman who told about losing her virginity to Saddam, his yellow eyes "were the eyes of death. He looked at me as if I were a corpse."

A nuclear bomb, in the hands of such a man, is bound to be cataclysmically dangerous, rendering him, as Hamza has put it in a recent television interview, all but "invincible": the "hero of the Arab world" and readier than ever to indulge his well-proven appetite for recklessness. The result - for Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and of course Israel - is almost too frightening to contemplate.

What then is to be done? In Hamza's view, there are only two ways to stop the current train of events from unfolding toward catastrophe. Best by far would be to get rid of Saddam himself. But this can only happen if the U.S. government either acts on its own to bring it about or provides the necessary lethal aid to the Iraqi opposition. Second best would be to begin an emergency program to deprive Saddam of the skills of his 25 top nuclear scientists, preferably by getting them out of the country.

Unmentioned by Hamza but certainly valuable are such initiatives, currently being considered or implemented by the Bush administration, as boost-phase missile defenses to protect our allies, energy substitutes to deprive Saddam of oil revenues, and a renewed embargo. But in the end, as this truly alarming book shows, which path we take is less important than recognizing how late the hour has grown, and how urgently we need to move the question of Iraq to the very top of our foreign-policy agenda.