I first met Nizar Hamdoon in mid-1985, when he was Iraq's immensely popular ambassador in Washington. He promoted the thesis that Iran had started the war with Iraq and bore the onus for its continuation, therefore the U.S. government should help Baghdad. Nizar made these points with a competence, reasonableness, and self-criticism rare in any diplomat, and extraordinary in one representing a brutal totalitarian thug.

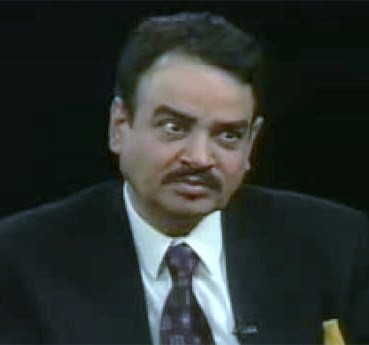

Nizar Hamdoon, 1944-2003. |

Nizar's method brought him great success. During his glory years as Iraqi ambassador in Washington, 1984-87, he had a reach, a public presence, and an impact that fellow ambassadors could only envy.

With me, as with so many others unsympathetic to the regime he represented, Nizar went out of his way to establish a rapport. He telephoned on a regular basis and visited my homes, first in Newport, R.I., then in Philadelphia. When my wife and I traveled to Kuwait in 1987, he arranged a side trip to Baghdad. He invited me to dinner at his Washington residence and in 1992 hosted a bus full of my organization's board members at his mission.

Nizar disappeared from view after he finished his second stint in the United States (as Iraq's United Nations ambassador) in 1998. I idly wondered from time to time how he was faring as the war unfolded in March-April of this year; I did not know even if he was still part of the regime. So an e-mail I received on May 15, 2003, just two weeks after major hostilities in Iraq had ended, from "nizarhamdoon@yahoo.com" certainly caught my eye, as did its enigmatic text:

Dear Daniel:

I have been here in NYC for a while under Chemo treatment. My cell phone if you like to call is 917-325-9252. I will be staying until first week of June.

Thanks, Nizar.

How did he get to the United States and how long had he been in New York? What would he reveal of his career and the regime he worked for now that Saddam Hussein was deposed? I had many questions built up over the nearly twenty years I had known him. Hoping to interview him for the Middle East Quarterly, I carried a list of twenty-eight questions and a tape recorder to our meeting on May 21 at (his choice) the Starbucks on the corner of 78th Street and Lexington in Manhattan.

We talked for nearly one and a half hours. I learned that he had had a medical emergency in March 2003, so he traveled without family to Amman, where ten days later he received a U.S. medical visa. He arrived in New York and underwent a chemotherapy treatment, then planned to rejoin his family in Iraq in early June. On arrival in New York, he told me, he moved into the Iraqi ambassador's residence (and his own home during 1992-98) on 80th Street, invited there by the then-Iraqi ambassador to the United Nations, Muhammad ad-Duri. When war broke out and ad-Duri fled the country, Nizar remained, inhabiting just one room, relying on a single local hire to take care of the place.

How could he travel to the United States when his regime was at war with the United States? Nizar said he was not at liberty to speak but would do so in time. The same applied to his experiences; I did not have a chance to ask any of the questions burning a hole in my pocket. But he did reply to several of my inquiries in a manner that amplifies the public remarks he made three weeks later to the Middle East Forum.

How could you, I asked him, a civilized person, represent the barbaric regime of Saddam Hussein? He pointed to two factors: fear and loyalty. Fear I understood, but loyalty? Yes, he replied, the ethic of loyalty is very deep in Iraqi society and even obtains in a case like this. He tried to explain but realized at a certain point I could not understand and we left it.

Were you tempted to defect? No, he likes it in the United States but feels rooted in Iraq – the society, the food, the atmosphere – and would not want to live here.

You took risks in your subtle presentation of the Iraqi case – conceding certain points in order to gain credibility; was this approved by Baghdad? No, and it got him in trouble on occasions. He was constantly instructed to bluster like other ambassadors.

He then told me of a 20-page personal letter he sent to Saddam Hussein in 1995 in which he told his boss what was on his mind. Why would you send such a letter? Nizar did not offer an explanation. To his surprise, Saddam widely distributed the letter for discussion among the leadership and eventually sent Nizar a personally-signed 75-page letter. Why would Saddam Hussein spend a day writing you a letter, I asked incredulously. Nizar shrugged: "That's what he decided to do." In the response, among many other points, Saddam accused Nizar of sending a copy of his letter to the CIA. That should have been the end of your career, at the least, I asked; why wasn't it? Again, Nizar did not convincingly reply; he said that Saddam sensed his loyalty and sincerity, and so did not punish him.

Nizar assured me that he had these letters; they and other documents formed an archive he would make public at the right time.

His career effectively ended in 2001, when a new Iraqi foreign minister pushed him out of the ministry. He was kicked upstairs to the president's office, where he served former foreign minister Tariq Aziz. But it was a purely ceremonial job; Aziz's only foreign portfolio was dealing with the Baath parties abroad and other friendlies. As Nizar oversaw the North American desk, that meant he handled minor-league matters like the anti-sanctions group, Voices in the Wilderness. He spent two hours a day in the office, surfed the Internet there, and went home. But he received his old salary and benefits.

The fact that Saddam Hussein remains on the loose meant that Nizar was both fearful and still burdened with a sense of loyalty to his old patron. In combination, these made him careful about what he said in public. But he raised the idea of giving a talk to the Middle East Forum, which he did on June 4, 2003. I believe it was his last public appearance. (An edited text of his presentation and the ensuing discussion was published in the Fall 2003 issue of the Middle East Quarterly.)

Daniel Pipes (L) and Nizar Hamdoon, June 4, 2003. |

Nizar Hamdoon died on July 4, 2003.

Daniel Pipes is publisher of the Middle East Quarterly.

Oct. 27, 2005 update: According to the Volcker report investigating corruption in the UN oil-for-food program, as summarized by the Houston Chronicle, Texas oil tycoon Oscar Wyatt Jr. curried favor with the Saddam Hussein regime by, among other things, "donating furniture to the country's mission at the United Nations and a car to the Iraqi Embassy in Washington. The report said that when Nizar Hamdoon, Iraq's one-time representative to the United Nations, became ill, Wyatt picked up some of his medical bills."

Oct. 4, 2011 update: I received a note today from Feisal Amin Rasoul al-Istrabadi, a former Iraqi ambassador to the United Nations and now director of the Center for the Study of the Middle East at Indiana University's Maurer School of Law in Bloomington:

I served as ambassador and deputy permanent representative of Iraq from 2004 until 2010, though I was on leave from that post after 2007.

On my arrival at Iraq Mission to the UN, the head of the Mission secretariat was a local hire who had been in that position since the days of the previous regime, and had served with Nizar Hamdoun. He told me that at one point, Hamdoun did indeed send a fifty-page letter addressed to Saddam Hussein criticizing Iraqi government policy at the time. He also told me that Saddam responded with a very long letter, on the order of the length you mention in your piece, apparently part of the gist of which was that Nizar himself was not entirely innocent of some of the accusations he leveled at Saddam, or something to that effect.

While I neither ever saw Nizar's letter nor Saddam's response, I felt it appropriate to confirm that what I was told about that particular correspondence confirmed what Nizar said to you.

Feb. 8, 2024 update: Over twenty year's after Nizar Hamdoon's death, his memoir has appeared in both Arabic and English. The English version, The Middleman: Ambassador Nizar Hamdoon's unpublished documents, correspondence, and reflections on his diplomatic role between Saddam Hussein's Iraq and the United States, runs 684 pages. He mentions me once:

On 9/12/1992, my old friend Daniel Pipes came to the mission. I knew him in academic political research circles since the 1980s, and he brought around thirty people of various ages and fields for me to speak with. The most challenging questions were related to Iraq's stance on the Arab-Israeli peace process. I said, based on my own thoughts unrelated to the current reality in Baghdad, that Iraq is besieged, not allowed to move, and no one listens to its opinion. Therefore, these circumstances must change if Iraq's opinion on the matter is required. Also, Iraq may reconsider its position in light of its understanding of the return on investment within the framework of a comprehensive deal, including lifting the embargo.