Even after his many years in power, Libya's Col. Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi continues to exert his political will at a frenzied pace. The latest efforts include: the near crippling of President Carter's re-election campaign through payments to brother Billy; declaring political union with Syria; providing support to Iran shortly after Iraq attacked it; accusing Saudi Arabia of placing itself "under U.S. occupation" (provoking a break in relations); mounting a war of nerves against U.S. reconnaissance planes near the Libyan coast; threatening Malta over oil exploration rigs in contested waters; bribing the Cyprus government to accept a transmitter for Libyan radio broadcasts; and flying Libyan troops to southern Chad to control the country and impose political union on it. Most recently, Qaddafi has been connected with the outbreak of violence by a Muslim group in northern Nigeria that left over 100 people dead.

Even after his many years in power, Libya's Col. Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi continues to exert his political will at a frenzied pace. The latest efforts include: the near crippling of President Carter's re-election campaign through payments to brother Billy; declaring political union with Syria; providing support to Iran shortly after Iraq attacked it; accusing Saudi Arabia of placing itself "under U.S. occupation" (provoking a break in relations); mounting a war of nerves against U.S. reconnaissance planes near the Libyan coast; threatening Malta over oil exploration rigs in contested waters; bribing the Cyprus government to accept a transmitter for Libyan radio broadcasts; and flying Libyan troops to southern Chad to control the country and impose political union on it. Most recently, Qaddafi has been connected with the outbreak of violence by a Muslim group in northern Nigeria that left over 100 people dead.

These are only the latest details of a grand plan for Libya. Qaddafi has involved himself in every Middle Eastern conflict, in Muslim causes as far away as the Philippines, and in "liberation" movements around the world. Libya has a key role in OPEC, serves as an arsenal for Soviet arms, and aspires to nuclear weapons of its own. Such actions have not been without consequence; they have made Libya, a country of three million people, an unexpectedly powerful force in world.

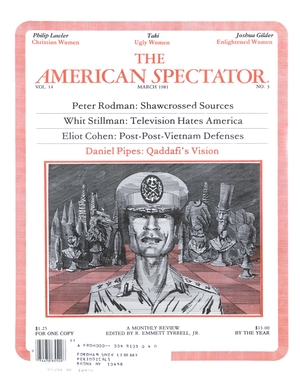

Qaddafi's Role

And Qaddafi can take credit for it. Before the discovery of oil in 1959, Libya was a primitive state, politically dependent on British and American aid and economically reliant on an unskilled workforce with an annual per capita income of $30. Libya's King Idris failed to wring any political and economic power from the country's oil, and so when Qaddafi took over the country in a bloodless coup on 1 September 1969, he inherited a sleepy state without international ambitions. Qaddafi lost no time stamping his vision on the country. Within a few months the new ruler felt secure enough to institute a provisional constitution, challenge the oil companies' control over petroleum production and pricing, and expel the British and Americans from their Libyan bases.

Exhilarated by these early successes, Qaddafi plunged into international affairs and overnight turned Libya into a significant actor on the world stage. Libya's new power flowed entirely from its oil, without which its influence would be no greater than that of, say, Chad or Niger. Yet billions of oil dollars alone do not account for Libyan strength: Kuwait and Abu Dhabi enjoy revenues comparable to Libya's but play smaller roles in international politics; their leaders lack the drive to push and fight. They lack Qaddafi's sense of mission.

Qaddafi looked normal when young. |

Qaddafi fights with unrelenting hostility against anything that obstructs Islam or Arabism. He can not forgive the Europeans for having colonized so much of the Muslim world and then imposing on it what he views as their weak, corrupt ways. He condemns the United States for exploiting Muslims economically and he regards Israel as the culmination of Western imperialism - not just the political control of a territory but its settlement by Europeans and their subsequent expulsion of its Muslim inhabitants. The continued existence of Israel symbolizes the impotence of Arabs and Muslims, a result of their internal divisions. Israel's destruction will be both the catalyst and symbol of Arab and Muslim unity.

To guide public affairs in Libya and around the world, Qaddafi has developed a political ideology of his own. He believes that the people's councils and Islamic socialism proposed in his Green Books can solve the perennial problems of the distribution of power and wealth. Neither bourgeois democratic nor Marxist authoritarian, neither capitalist nor Communist, his ideas constitute a "third theory." Since the introduction of his third way in 1973, Qaddafi has increasingly insisted on its application in Libya and in other countries where he carries influence; his enthusiasm for the Green Books may now even eclipse his devotion to the Qur'an. This accounts for the increasingly erratic regulations concerning Islam which emanate from Libya (such as a change in the first year of the Islamic calendar from 622 A.D. to 632). Although Qaddafi's antipathy to both capitalism and Communism might imply a neutral stance toward the great powers, in fact he favors the Soviet bloc, for the West is associated with colonialism and support for Israel, while the Soviet Union arms and helps Qaddafi's government.

Qaddafi occasionally does speak out about the plight of Muslim minorities in Communist countries, especially Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. He has not publicly discussed Muslims in the Soviet Union, however, though reports have circulated that he brought up this topic during a 1977 meeting with Brezhnev in Moscow: "Brezhnev reportedly raised the possibility of opening a Soviet consulate in Benghazi, whereupon Qaddafi said that would be all right if Libya could open one in Tashkent. When Brezhnev asked why Tashkent, Qaddafi was quoted as saving, 'Because I understand there are a lot of Muslims in that part of Russia [sic] and I would like to take care of them.' The matter was never raised again."

Finally, Qaddafi is drawn to revolutionary ferment; temperamentally he cannot endure tranquility. In his private life, in Libyan politics, in the world at large, Qaddafi constantly creates turbulence, upsets the status quo, and revels in action for its own sake. No ruler has resigned so many times, tried so often to unite with other states, or meddled so irresponsibly around the world. This personal inclination goes far to explain the effervescence of Libyan politics since 1969.

Translating these principles into action, Qaddafi helps Muslims against non-Muslims, Arabs against non-Arabs, revolutionaries against the status quo, republicans against monarchs, and absolutely anyone who hates Israel.

Difficult choices arise only rarely. Revolutionary Algeria supports the creation of a new independent Arab state of the Western Sahara by the Polisario; monarchical Morocco is battling to include Western Sahara within its borders. Qaddafi agonized for months; while he disapproves of dividing up the Arab world further by the creation of a new state, he instinctively sympathizes with the Polisario. In the end, Qaddafi followed his emotions and Libya for some years supplied most of the Polisario's matériel. Support for the Ethiopian government after 1975 against Eritrean secessionists also meant placing emotions ahead of ideology. But such dilemmas have been few; for the most part, Qaddafi's preferences have been completely predictable.

Global Activities

Indeed, the bizarre quality of Qaddafi's actions results from his utter certainty and constancy. He is completely determined and committed; he has a vision of truth and does everything in his power to advance it. The colonel, for example, encourages any measure against Israel, opposing the Jewish state in every international forum, however inappropriate, embracing terrorism without qualms, and even proposing such schemes as the torpedoing of the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth II as it carried Jews to Israel to celebrate that country's twenty-fifth anniversary. He is unquestionably fanatical but rarely erratic, unpredictable, or devious.

In some ways, Qaddafi resembles two other wildly eccentric African despots, Idi Amin and Jean-Bedel Bokassa. Like them, he has sponsored a long list of grotesque and malevolent activities and sneered at worldwide disapproval. Who but Qaddafi would unearth the bones of Italians buried in Libya, build a 200-mile concrete wall to protect himself from a neighbor (Egypt), or sign a mutual defense treaty with Guinea? Offtimes he appears like a character out of opera bouffe or an Evelyn Waugh novel.

Yet there is more to Qaddafi. Unlike Amin and Bokassa, he displays no personal taste for barbarism and cruelty. Since 1969 Libya has witnessed few atrocities and its repression is moderate by world standards. In fact, political executions appear not to have taken place until April 1977, more than seven years after Qaddafi came to power. Although domestic brutality increased in 1980, it is still very far from recent ravages in Uganda, Central Africa, or Equatorial Guinea, to say nothing of Indochina. Moreover, where Amin and Bokassa built up whimsical cults of self-aggrandizement, Qaddafi has an ideology and acts according to principles. In contrast to Amin's and Bokassa's splendiferous ways, Qaddafi lives modestly. Recently, however, a cult of personality has been building around Qaddafi; among other acts of adulation, he accepts veneration as a messiah figure from the Children of God, an American Jesus freak movement. Finally, equating Qaddafi with Amin and Bokassa wrongly implies that he is a figure of only regional importance. He is much more.

Libya has a huge income from oil (at one time it reaching $20 billion a year) but a miniscule, unskilled population of about three million people. From this odd blend, Qaddafi has devised novel methods of conducting an adventurous foreign policy based not on human resources, but on wealth and will power. Qaddafi's foreign efforts invariably involve giving money, buying alien services, and the energetic use of Libya's limited facilities.

Libya's aids government and opposition groups about equally. Over forty governments have received funds for non-military purposes; although most of them are Arab or Muslim, Qaddafi makes real efforts to reach other countries too. Some money goes to humanitarian causes, such as caring for flood and earthquake victims in Pakistan or feeding the peoples struck by famine in Somalia. Larger sums go for economic development; a pelletization plant in Sudan, and a wide variety of joint ventures (shipping companies, trading firms, factories, agribusinesses). Libyan joint bank offices have opened in eighteen countries; Islamic schools, cultural centers, and mosques have been built throughout the Muslim world with Libyan funds. Qaddafi even provided a loan for the construction of a mosque to American Black Muslims in return for their adoption of a less idiosyncratic form of Islam.

Small gifts win goodwill in remote places. The poorest countries in Africa (Burundi, Malagasy, Rwanda, Togo) receive development aid, Sri Lanka got $1 million for hosting the non-aligned conference of 1977, and Tonga plans to extend the main airstrip at the Fua'amotu airport with $3 million from Libya. Three near-bankrupt leftist governments in the Caribbean (Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica) recently accepted emergency aid, while Soviet clients nearer to Libya (Angola, Ethiopia, South Yemen) also profited from Libyan largesse. Libya's six contiguous neighbors have all taken its money for non-military purposes, as have all the countries bordering on Israel.

Military aid is also widely distributed. Although Qaddafi repeatedly assured France during the years 1971-74 that Libyan Mirage planes had not been made available to Egypt, President Sadat later disclosed that they had. When Israel shot down five Syrian MiGs in June 1979, Tripoli immediately offered to replace them. Turkish troops may have used Libyan arms during its 1974 invasion of Cyprus. Following the Egypt-Israel peace treaty, Qaddafi offered extensive military aid to the Sudan if Ja'far an-Numayri broke with Sadat. The Maldive Islands received two radar-equipped boats for its coast guard. A few up-to-date weapons have made a big difference for the armed forces of countries like Burundi, Central Africa, Mauritania, and Niger.

Qaddafi rewards governments in other ways as well. He sells oil, even at ever higher prices, as a favor to be exploited for political ends. Threats of an oil boycott convinced Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines to accept Libyan mediation in his struggle with Muslim rebels. Selling discounted oil to Malta kept Dom Mintoff subservient for years. An occasional small gesture of generosity can make a big impression: Qaddafi won favor in Sri Lanka by paying for four years' worth of tea in advance. Libyan authorities also win influence by paying premium prices for the vast array of foreign goods and services they purchase. When buying products such as steel, cement, and foodstuffs, which are homogeneous in quality and uniform in price, Libyan officials often choose the seller who is most politically cooperative.

Libya needs tens of thousands of technicians, educators, clerks, construction laborers, and unskilled workers; intense international competition to supply this labor again permits Qaddafi to extract political concessions. Egypt and Tunisia provided the most manpower for Libya during the 1970s, but crises with these two countries (peace with Israel, the Gafsa incident) led to a reduction of their workers in favor of laborers from Turkey, Pakistan, India, and other points east. Such diversification wins Libya influence and prestige in many countries while reducing its vulnerability to any one supplier.

Libya invests very little in the less developed countries, preferring the larger, more stable markets of the West. Here too Qaddafi exploits the power of his money, though usually with less success. For example, when the Italian newspaper La Stampa published a satire on Qaddafi in 1974, Qaddafi demanded the dismissal of its Jewish editor and threatened to break diplomatic relations with Italy if nor satisfied; he was not and the furor died down. Two years later, in perhaps a related development, Libya purchased $413 million worth of stock in Fiat, La Stampa's parent company.

True to his anarchistic bent, Qaddafi supports as many opposition movements as established governments. Here, the Muslim component of Qaddafi's ideology shows more clearly. In Chad, Muslim rebels who took up arms in 1966 against the central government run by Christians and animists received significant aid from Qaddafi from 1970. Eritrean secessionists portray their efforts as a Muslim movement in order to win Libyan aid against the central government of Christian Ethiopia. In the Lebanese civil war of 1975-77, Qaddafi of course backed the more Muslim faction, the National Front. Similar Muslim fellow-feeling impels Qaddafi to give unbounded support to the PLO. Further east, he helps Muslim rebels in Thailand and the Philippines.

Qaddafi also supports activists Muslims struggling against governments run by less zealous Muslims. He aids several subversive Muslim organizations in Egypt in the hope that one of them will either assassinate leading Egyptian politicians or carry out a coup. Before Libyan relations with the Turkish government warmed up, Qaddafi was accused of aiding its Muslim extremist opponents. Reports came to light that Qaddafi funded the armed group that took over the Great Mosque in Mecca in November 1979; the two Libyans present were his agents. Libyan support for the Islamic opposition to the shah began in the mid-170s, and Qaddafi now claims to have been the first leader outside Iran to aid Khomeini. And in a demonstration that Islam can be more important to Qaddafi than geopolitical alliances, Libyan weapons for a time were sent to the Islamic groups fighting the government in Afghanistan after the Soviet-backed coup in April 1978.

Many Arab regimes fail to meet Qaddafi's standards, so he has often instigated coups against them. He has been accused of trying to topple the governments of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, the Sudan, and Jordan-and in many cases, of trying more than once. Even though the Libyan government usually denied any involvement in these failed coups, it sometimes showed its hand while they were in progress. King Hasan of Morocco came close to losing his life in a 1971 conspiracy, at which time Qaddafi placed his troops on alert and announced their availability to aid the rebels should the "reactionary" forces challenge their rule; to Libya's acute embarrassment and disappointment, King Hasan quickly regained power. The conspiracy against the Sudanese government which unfolded in July 1976 was hatched in Libya, where the conspirators were trained, armed, and quartered; while the coup attempt was in progress, Qaddafi sent Libyan planes over Khartoum.

Tools of Global Influence

Qaddafi extends aid to virtually every West European separatist movement that turns to him, including secessionist groups of Canary Islanders, Basques, Northern Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Bretons, Corsicans, and Sardinians. Aiding these rebels gives Qaddafi some clout; but permitting outlawed groups-almost always non-European-to open offices, even headquarters, in Libya gives him even greater control.

Organizations represented in Tripoli have included the Polisario (Western Sahara), Union democratique republicaine du Mali, Tunisian Resistance Army, Frolinat (Chad), Ansar (Sudan), Front for the Liberation of Egypt, Palestine Liberation Front, Popular Front for the Liberation of Oman and the Arab [Persian] Gulf, Arabistan Liberation Movement (Iran), Pattani National Liberation Front (Thailand), Moro National Liberation front (the Philippines), as well as movements directed against the current regimes in Morocco, Mauritania, and Afghanistan.

Qaddafi funds these groups, arms them, and provides access to Libyan training camps and radio. Because he can take away all that he gives, these revolutionary organizations have to listen to Qaddafi. This became evident in December 1976 during negotiations between the Philippine government and the Moro National Liberation Front; to insure their success, Qaddafi virtually excluded the Front from the talks and came to terms on their behalf with the Manila regime.

Qaddafi exercises an even tighter rein over the foreign legions he sponsors. These three legions are staffed, even directed, by foreigners and they each have a distinct mission: religious, military, and terrorist. The Association for the Propagation of Islam, founded in 1970, trains Muslim preachers sympathetic to Qaddafi's intolerant Islam and sends them abroad with ample funds. By 1977, the Association fielded 350 missionaries, only two of whom were Libyans; most of them have been sent to sub-Saharan Africa, that last great battleground for souls between Christian and Muslim. Others have been sent to Malaysian in an attempt to upset that country's delicate religious balance.

The Bureau of Export Revolution (known also as Le Bureau arabe des liaisons) runs commando camps for foreigners in Libya; six near the Mediterranean coast, four on the border with Tunisia, and one in the heart of the country, at Sebha. Egyptians, Tunisians and other Arabs, sub-Saharan Africans, Pakistanis, Indians, Vietnamese, North Koreans, and West Europeans participate, but there are no Cubans or Soviets, and the organization is run by Palestinians. The troops, numbering about 7,000, are well paid, well trained, highly politicized, and strictly disciplined. Some soldiers sign up abroad, but most, threatened with expulsion for having entered Libya illegally in search of work, prefer military service for the Bureau instead.

Soldiers from the camps have often ventured outside Libya, assisting the Polisario (via a desert route dubbed the "Qaddafi trail"), occupying the Aozou strip in northern Chad, and fighting in Chad's civil war. Others staged a coup in the Sudan and aided three African tyrants: Amin, Bokassa, and Francisco Macias Nguemo of Equatorial Guinea.

Tanzanian troops threatened to overthrow Idi Amin in early 1979, so Qaddafi sent 1,500 Libyans and legionnaires to Uganda. (Before leaving Libya, the soldiers were told they were being sent to Malta to participate in celebrations marking the withdrawal of British troops.) When Amin's support melted away, they were overwhelmed and the 1,100 survivors captured. Qaddafi paid the Tanzanians $40 million for their return.

On the morning of 27 January 1980, three hundred legionnaires, soldiers of the Tunisian Resistance Army attacked the town of Gafsa in western Tunisia. Some had made their way by land from Libya, others had flown to Algiers from Libya and posed as a sports group before making their way to the border. Libyan propaganda had convinced them that as soon as they raised the flag of rebellion, massive popular support in Tunisia would help them to vanquish the Bourguiba regime. In fact, they found no local sympathy and the government easily regained control.

Until 1975, the Libyan government relied on independent foreign groups to undertake its terrorist missions. In that year, the establishment of a terrorist foreign legion, the Service special des renseignements, made it possible for Qaddafi to initiate and control hijackings, assassinations, sabotage, and kidnapping. As observed in Africa Contemporary Record, Qaddafi had become omnipresent by mid-1976:

In addition to the plan to kidnap Abdul Menim Houni at Rome airport in March, and the assassination plots in Egypt and Tunisia the same month, he was accused in May of planning sabotage in the Nile Delta and of arming terrorists in Iran. In July he was charged with masterminding the coups attempt in Sudan, and in August, with responsibility for bombings in Egypt and for an attack on an El Al plane in Istanbul. Also in August, Sadat claimed Gaddafi and George Habash of the PFLP had directed the Entebbe hijacking of an Air France plane at the end of June.

In a July 1976 interview, Qaddafi defended terrorism, arguing that the use of force by oppressed peoples fighting for liberation is proper.

Qaddafi provides terrorists with money, weapons, training, and false documents. The diplomatic pouches and secure cables of Libyan embassies afford an invaluable network for supplies and information. The Palestinians who killed eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics received their weapons through the Libyan diplomatic pouch (and those killed by the West German police received state funerals in Libya). Libya also serves as a favorite refuge for assorted desperadoes. According to President Sadat, Illitch Ramires Sanchez ("Carlos"), the world's most notorious terrorist, lived for two years in a small coastal hotel near Tripoli; the same hotel housed the five Japanese Red Army members who attacked the American consulate in Kuala Lumpur in 1975 as well as the German anarchist Hans Joachim Klein, who was wounded in the kidnapping of OPEC ministers in Vienna in December 1975. In addition, Idi Amin probably stayed there for a time after his overthrow.

Qaddafi does not restrict the use of terror to foreigners. During the spring of 1980, Qaddafi's agents hunted down Libyan exiles who opposed his regime. Their murder of four dissidents in Rome, two in London, and one each in Athens, Beirut, Bonn, and Milan aroused international opprobrium. Most were shot, but one was strangled and another decapitated. Threats against dissident Libyan students living in the United States led Washington to expel several Libyan diplomats and nearly caused a break in relations.

Qaddafi uses his international connections as an Arab and a Muslim to expand Libya's influence. Under the guise of working to forge a single Arab nation, he has attempted to unite Libya with a dizzying number of other countries, including the Western Sahara, Morocco, Mauritania, Malta (only Qaddafi sees Malta as Arab), Egypt, the Sudan, Syria, and Chad. In each instance, negotiations broke down when the other side began to appreciate Qaddafi's intentions to dominate the union.

Islam plays an even greater role in Qaddafi's foreign relations. By convincing them to convert from Christianity ("the religion of imperialism") to Islam, Qaddafi forged bonds with two African strongmen: Albert-Bernard Bongo, president of Gabon, in September 1973, and Jean-Bedel Bokassa, president (and later emperor) of Central Africa, in October 1976. Qaddafi was even present in the mosque in Bangui, Central Africa, when Bokassa converted. Subsequently, both Bongo and Bokassa wore their Islam lightly-confirming the political nature of their conversions. Libyan influence is also discernible in the Algerian National Charter of June 1976, which made Islam the religion of state, and in the Mauritanian decree of June 1978 which established Islamic precepts as the law of the land.

But Qaddafi has been even more unorthodox in his methods. During the November 1972 unity talks in Tripoli between North and South Yemen, he threatened to detain their diplomats until they reached an agreement (they did). He helped to foil a coup attempt against Sudanese President Numayri in July 1971, by forcing down a BOAC plane flying over Libya with the coup's two leaders on board. They were held in Libya and eventually turned over to the Sudanese government for execution. Musa as-Sadr leader of the Twelve Shi'is in Lebanon, disappeared while on a state visit to Libya in August 1978. Libyan authorities claim he left Tripoli on Alitalia flight 881 to Rome on 31 August, but investigations have clearly shown that he never left Libya. It appears that Sadr, an invited guest of state, was murdered by his Libyan hosts.

Qaddafi reacted with astounding greediness to the discovery of oil on the continental shelf between Libya and its oil-poor neighbors, Tunisia and Malta. In January 1975, Malta proposed to divide the shelf midway between the two countries. In response, Libya claimed everything beyond twelve miles of Maltese territorial waters. In May 1976, the two countries agreed to refer their dispute to the International Court in the Hague, as did Libya and Tunisia three months later. Since then, the Libyans have placed exploration platforms in the contested waters on four different occasions, one time nearly provoking war. In a tauntingly aggressive move, government maps of Libya published in September 1976 included about 7,500 square miles of Algeria,, a similar amount of Niger, and 37,000 square miles of Chad. Qaddafi made no effort to control the Algerian territory, but the northernmost portions of Chad (known as the Aozou strip) and Niger were at the time already under Libyan control.

When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan announced he would build an "Islamic bomb," Qaddafi readily volunteered to finance the research. Libyan participation ceased to be merely financial in mid-1979 when a truck in Niger carrying twenty tons of 70 percent uranate, known as "yellow cake," disappeared from its normal route to the sea. Weeks later, nomads found the truck, overturned and empty, in the part of Niger under de facto Libyan control. In return for research assistance and the uranate, Pakistan reportedly will give Qaddafi the first one or two bombs it produces. According to The Christian Science Monitor, Qaddafi "may use the bomb to blow up the Suez Canal as a personal gesture of hatred for President Anwar Sadat."

A Record of Futility

For all Qaddafi's hyperactivity, he rarely gets his way; empty promises and fanaticism on his part have repeatedly undermined his ceaseless efforts to project power. Talking big but paying small has disappointed many potential allies, particularly in Africa. Within two years of his conversion to Islam, Gabonese President Bongo abrogated all the cooperation agreements he had signed with Libya because Qaddafi had not honored them. "The [Arabs] are not serious people and they do not keep agreements signed by them," he concluded. More recently, Qaddafi convinced the Maltese to terminate 181 years of British military presence on their island by promising to make up lost revenues (which amounted to about one-third of the national budget). But when it came time to pay, Qaddafi subjected Dom Mintoff to a humiliating inquisition at the hands of a people's council. In the end, the Maltese received no money from Libya and blamed their economic plight squarely on Qaddafi.

But even when he does deliver, Qaddafi often alienates recipients by demanding too much as a quid pro quo. For example, he insisted that Nepal break diplomatic relations with Israel in return for $50,000 in disaster relief. Few states, even small ones, sell their foreign policy that cheaply.

Over the past decade Qaddafi's radical fervor has cost him nearly all his allies. He simply never knows when to desist. The Tunisians endured sabotage, assassination plots, and aggression over contested oil fields, until the attack on Gafsa finally expended their good will. Qaddafi's faction in Chad turned against him when Libya claimed a slice of Chad's territory. Attempts to unite with Egypt soured to the point that Qaddafi and Sadat sought to assassinate each other. Extreme anti-Israel sentiment did not prevent a break in relations with the PLO during 1979, and its expulsion from Libya. Khomeini cannot forgive Qaddafi for murdering Musa as-Sadr, his relative by marriage. Qaddafi is a national villain in Uganda, Central Africa, and the Philippines; only Algeria and Pakistan have managed to maintain steadily good relations. Even though international representation in Libya has tripled since 1969, the country is isolated; only oil revenues buy enough friends to keep it from becoming a pariah.

Qaddafi has won many battles but not a single war. The Polisario is losing, the Gafsa attack failed, Sadat persevered in making peace with Israel, Chad degenerated into anarchy, Idi Amin and Bokassa were overthrown, Eritreans and Ethiopians reached a stand-off, Israel withstood terrorism, the Mecca mosque gambit failed bloodily, the National Front in Lebanon disintegrated, Thai and Philippine rebellions ground down to a halt, and the Billy Carter caper came to nothing. Not one of Qaddafi's attempts at coups d'êtat has toppled a government, not one rebellious force has succeeded, no separatists have established a new state, no terrorist campaign has broken a people's resolve, no plan for union has been carried through, and no country save Libya follows the "third theory." Qaddafi has reaped bitterness and destruction without attaining any of his goals. Greater futility can scarcely be imagined.

Qaddafi had changed by 2010. |

News today, "Gadaffi to pay £2bn to victims of IRA bombs," symbolically captures both these thoughts. On the one hand, the funds go to Irish victims of his decades-ago all-points-terrorism; on the other, these payments argue for the pointlessness of all that activity documented in this article.