I doubt that I was alone in being perplexed by the news from Lebanon during the summer of 1982. Even knowing the record of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) toward Israel had not prepared me to think that it terrorized Palestinians, too - yet such, it turned out, had been the case in South Lebanon from 1975 to 1982. This not only contradicted theories about the way in which guerrillas depend on the support of the local population among whom they live; it also made no sense that the PLO would alienate its own constituency

I doubt that I was alone in being perplexed by the news from Lebanon during the summer of 1982. Even knowing the record of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) toward Israel had not prepared me to think that it terrorized Palestinians, too - yet such, it turned out, had been the case in South Lebanon from 1975 to 1982. This not only contradicted theories about the way in which guerrillas depend on the support of the local population among whom they live; it also made no sense that the PLO would alienate its own constituency

Then, the PLO military defeat highlighted another anomaly: why was it that an organization enjoying massive international acclaim failed to achieve even a single one of its military objectives against Israel? Why did political successes not translate into strength on the ground?

The continued fever pitch of PLO rhetoric in the aftermath of Lebanon raised further questions: were PLO leaders not aware of the Israeli bulldozers at work on the West Bank, and the short time left before that region became irreversibly part of Israel? Were they oblivious to the absurdity of planning to destroy "the Zionist entity" when their fighters were holed up in camps many hundreds of miles from Israel's borders?

Finally, in perhaps the strangest anomaly of all, the launching of the Reagan initiative in September 1982 turned the world's eyes once more on the PLO, as though its response were the key to a peace settlement in the Middle East. Could it really be that an organization of refugees had the power to dictate the position of twenty sovereign Arab states, including some of the richest countries on earth, on so large and important an issue as Arab relations with Israel?

On reflection I reached the conclusion that these paradoxes all derive from one critical fact: support for the PLO comes much more from the Arab states than from the Palestinians themselves. It is Arab help that molds the PLO, that makes it unlike other irredentist movements, and that renders its role so elusive. To understand why the Arab rulers support the PLO, and what that support means, we must begin with pan-Arabism, the ideology that explains so much about political life in the Middle East.

Pan-Arabism

Public life in the modern Middle East is dominated by a contest between two political systems, the traditional and the modern, the Muslim and the Western. While similar contests are taking place in China, India, and Africa, nowhere are the two sides so evenly matched, and nowhere do the contestants disagree on so many issues, as in the Middle East. During the period of colonization Europeans often flattered themselves with the thought that Western ways had everywhere supplanted traditional attitudes and customs. But in most cases old practices had merely become less visible. Phrasing and appearances usually changed more than actual sentiments; despite the alteration of forms, feelings remained largely constant. What makes Middle East politics - including the politics of the PLO - perplexing to a Westerner is precisely the mix of these traditional Muslim elements with the more familiar Occidental ones.

This took many forms. For one, the Muslim legacy of a wide separation between ruler and ruled obstructed the adoption of democratic processes throughout the Middle East. In the course of adopting European ways, most twentieth-century Muslim leaders did in fact institute Western-style elections, but the difference in political background meant that they regarded citizen participation more as a way to prod the populace for support than as a means of creating legitimacy or stability. Practices which came into being after independence betrayed this tendency: one-party elections in Syria, ballots for lesser officials but not for the head of government in Egypt, political parties representing religious groups in Lebanon, democracy alternating with military rule in Turkey, and manipulated elections in revolutionary Iran. Muslim populaces understood the authorities' purposes and responded warily; they had modest expectations when they did show up at the polls.

As with elections, nationalism too underwent a metamorphosis in the Middle East. A product of special European circumstances, nationalism had developed out of the slow accumulation of common experience in England, France, Germany, and elsewhere in Europe. Shared language, religion, culture, territory, history, and racial characteristics all contributed to this process, with no single factor having decisive importance.

Nothing comparable to the nations of Europe existed in the Muslim world, especially not in the Middle East. There the guiding principle of political allegiance was pan-Islam, the doctrine that all Muslims should live together in one state under a single ruler, or, failing this, that all Muslim states live at peace with one another. Despite their historic inability to observe the ideals of pan-Islamic unity, Muslims always cherished this goal of brotherhood and emphasized the bonds of Islam. Differences of language, ethnic identity, and other traits did not prevent them from viewing one another as brethren in the faith (in contrast, non-Muslims usually appeared to them to be potential enemies). Muslims paid little attention to nations; loyalties tended to be directed either toward the whole brotherhood of Islam or toward the local community (village, tribe, city quarter, or religious order). Larger territorial units had little political meaning; even the most established of them, such as Egypt or Iran, were cultural abstractions like New England or Scandinavia, not political entities corresponding to existing boundaries.

Whereas nationalism glorifies precisely that mixture of local qualities that makes every people unique, pan-Islam ignores such qualities as language and folk culture and urges instead the unity of believers within a single state. Because Muslim and Western forms of allegiance took virtually opposite forms, nationalism was transmuted when it came into contact with pan-Islamic impulses.

Attracted to nationalism but wedded to pan-Islam, Muslims attempted to bridge the differences through compromise. Among Arabic-speaking Muslims, it was the drive to unify all Arabs within a single state, known as pan-Arabism, that won the greatest support. Believing that all Arabic-speakers form a single nation, pan-Arabists reject existing boundaries between Arabs as lines drawn by imperial powers to prevent the Arab nation from uniting and gaining its full strength. They hope some day to erase those lines and create a single Arab state reaching from Morocco to Iraq.

Pan-Arabism rather exactly includes both Muslim and Western elements; its appeal to the unity of Muslims recalls pan-Islam, while its stress on language as the definition of political identity recalls nationalism. (It may be hard to imagine, but even among Arabs, language had little political importance before the twentieth century and had almost no role in defining political loyalties; the very notion of an Arab people is thus a result of European influence.) In short, pan-Arabism is a "nationalized" version of pan-Islam. It became a major ideology by the 1920s and a powerful force during the 1950s.

Thanks to pan-Arabism, Arab leaders are uniquely embroiled in one another's affairs. Pan-Arabism sparks grand assertions of friendship, stimulates reciprocal claims, and justifies the habitual flouting of those restraints that normally exist among sovereign states. Thus Arabs find it unremarkable that Algiers should host a movement planning to overthrow the Egyptian regime, that Cairo should send soldiers to Iraq, that Baghdad should plot coups against Syria, that Damascus should occupy northern Lebanon, that Beirut should solicit Saudi advice on negotiations with Israel, that Riyadh should support North Yemen against South Yemen, that the two Yemens should discuss unification between bouts of war - and so on. Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi of Libya may be reviled for his mischief, but no one denies him the prerogative of involving himself in the affairs of his Arab brethren. Pan-Arabism, by inspiring the leaders of twenty-odd states to unite, incites unabashed interference in their mutual affairs.

The Arab states thus differ from the Spanish-speaking countries of South America which accept their separate political identities and do not dream of unifying; instead, these states resemble divided countries such as East and West Germany, North and South Korea, or Communist and Nationalist China, in the feeling of being unnaturally separated and in the expectation of eventual union.

The immense appeal of pan-Arabism helps explain many of the Middle East's most distinctive political qualities, including its volatility and the predominance of local conflicts over the Soviet-American rivalry. It also accounts for the involvement of the Arab states in Palestinian affairs, and the special role of the PLO. In the early part of the twentieth century Zionist efforts to build a Jewish community in Palestine, and eventually to establish a sovereign state in the area, stimulated the Arabs of the region to seek help from neighboring Arab states; their cry tapped the powerful vein of pan-Arabist feeling. (The support they received bore some resemblance to the support given by Diaspora Jewish to the Zionists, for Jews and Muslims emphasize similar bonds of community.) Pan-Arabists then seized on the Palestine conflict and made it the centerpiece of their program; in part they did so because the prospect of losing to the Jews was particularly ignominious, in part because Palestine had strong Islamic associations, in part because the Zionist challenge looked so easy to defeat.

Pan-Arabism then transformed what would have been an obscure clash over territory into one of the greatest, most significant land conflicts of the age. If not for the Arabs' impulse to engage in one another's affairs, the Palestinian cause would probably have remained as peripheral to world politics as that of the Armenians or the Eritreans. But the pan-Arabist focus on Zionism as the paramount enemy made the fate of the Palestinians a matter of direct concern to every government between Libya and Iraq. As the unifying element in pan-Arabism, the cause of the destruction of Israel acquired a symbolic importance out of proportion to the issues at hand. With time, it even took on independent existence, bearing its own mystique.

As the principal goal of pan-Arabist politics, the destruction of Israel also became a way for government to assert their legitimacy; many rulers - Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, the Syrian and Iraqi Ba'thists, and, especially, Qaddafi - made their involvement in the "Palestinian cause" a leading warrant of their worthiness to rule. Conversely, the credentials of Arab rulers who did not hew to the standard line on Israel were brought into question (indeed it was expected that any Arab leader who accepted Israel would pay with his life, in the manner of King Abdallah of Jordan, Anwar as-Sadat, and Bashir Gemayel).

The conflict with Israel thus came to bear on the authority of Arab regimes; giving aid to the Palestinian cause strengthened rulers against challenges from within or meddling from abroad. With the years, Israel's military prowess rendered the idea of destroying it increasingly senseless - yet the failure to find other sources of political legitimacy meant that Arab rulers continued to depend on anti-Zionism.

The PLO, Pan-Arabism's Child

The significance of anti-Zionism reached so far beyond Palestine that Palestinian Arabs themselves played for the most part a secondary, or lesser, role in it. It was the Arab states - Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq - that led the struggle against the Jews. From the handful of independent Arab governments in the 1920s to the more than twenty members of the Arab League today, the Arab states have controlled the Palestinian movement by providing massive financial, military, and political support. Even before 1948, Palestinians relied heavily on the money, arms, and diplomatic pressure of the Arab states. From the declaration of Israeli independence until the 1967 war, the states so dominated anti-Zionism that they even suppressed Palestinian efforts to organize. After 1967, when the states retreated in defeat, the Palestinians re-emerged as a distinctive force in the form of the PLO; but even then it was the states that contributed nearly all the resources.

The benefits to the PLO have been staggering. Financial statistics cannot be specified, for the PLO does not circulate its budget, but published reports indicate that in recent years the organization received about $250 million yearly from Saudi Arabia and smaller amounts from other oil states, including $60 million a year from Kuwait. At a summit conference in Baghdad in 1978, the Arab states promised another $100 million annually. Non-Arab governments (such as the Soviet bloc) also gave generously; and if these insisted on cash for arms, third parties might be induced to pick up the tab, as in April 1982 when the Saudis promised $250 million to pay for weapons from Bulgaria, Hungary, and East Germany. When the PLO requested help from the Arab states last summer, the Algerian foreign minister called in the Soviet ambassador in Algiers at four in the morning and gave him a check for $20 million; the weapons reportedly arrived in Beirut several days later by air.

King Fahd of Saudi Arabia (L) hugs Yasir Arafat. |

About 5 to 10 percent of the pay of the 300,000 Palestinians working in the Gulf states is withheld by the governments there and earmarked for the PLO; were all of this money to reach its stated destination (which is not the case), it would provide the PLO with about another $250 million a year. Aid also comes from the farther away, from radical and Islamic groups around the world: in January 1983, for instance, the Malaysian Islamic Youth Movement in Kuala Lumpur gave a check for $80,000 to the local PLO representative. Terrorist activities have also proved a source of funds; the PLO reportedly received $20 million in December 1975 for releasing the OPEC oil ministers it had helped take hostage.

With this capital, the PLO was able to start large-scale business enterprises. In Lebanon, it ran a conglomerate called Samad ("Steadfast") whose 10,000 employees and estimated $40-million gross revenues in 1980 made it one of the country's largest firms. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), an organizational member of the PLO, achieved a near-monopoly over steel products in South Lebanon during the late 1970s by importing steel from the Soviet bloc at concessionary prices and paying no import duties (the PLO controlled the ports of Sidon and Tyre). Its factory, the Modern Mechanized Establishment near Sidon, undercut competitors and drove them out of business; then it raised prices and reaped huge profits. Many Lebanese believed that predatory pricing was integral to the PLO's plans to retain control over South Lebanon. In addition to its local investments - a hotel in Lebanon, a chicken farm in Syria - the PLO owns a portfolio of investments in the industrial states, including a disco club in Italy and an airline in Belgium.

The PLO also controlled most of the approximately $30 million a year sent by the Arab governments to the West Bank and Gaza, though on some occasions Arab states themselves became directly involved. For example, Mayor Elias Freij of Bethlehem received $600,000 from Kuwait in 1977, reportedly in exchange for refraining from speaking of peaceful coexistence with Israel.

All in all, the PLO's annual budget in recent years has been estimated at about $1 billion, prompting Time to call it "probably the richest, best-financed revolutionary-terrorist organization in history." Its leaders could enjoy an unusually opulent style of life; on one occasion, three PLO directors lost $250,000 of the organization's money at the gambling tables. If Yasir Arafat maintained an abstemious way of life, other of the top PLO brass were notorious for high living; Zuhayr Muhsin, head of As-Sa'iqa, was assassinated while residing in a luxury hotel on the Riviera.

Yasir Arafat at the United Nations. |

Nor could any other liberation group dream of winning the diplomatic standing awarded to the PLO. Two milestones stand out, the 1974 Arab decision at Rabat to make the PLO the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people" and recognition of the PLO by the United Nations a year later, culminating in Yasir Arafat's appearance before the General Assembly. During the 1970s, most other international bodies granted observer status to the PLO, which also won the right to open diplomatic missions in several dozen countries. The pressure on its behalf was intense: any government that resisted recognizing the PLO was threatened with oil boycotts, trade sanctions, and the like. Allowing the PLO an office was a minimal price for countries like Japan or Turkey to pay for promised access to oil, employment opportunity, and greater foreign sales. Iraq reportedly offered Spain an oil shipment worth $18 million for a change in attitude toward the PLO.

Under the States' Thumb

Dependence on the favor of Arab rulers accounts for the paradoxes posed at the beginning of this inquiry: the illusion of power, extremist ideology, inefficacy, and brutality.

The Illusion of Power. Support from the Arab states explains the anomaly of a refugee organization seeming to signal twenty-odd sovereign states what moves to make. It is true that the Arab states listen to the PLO and key their policies to its decisions; but its decisions, in turn, are little more than statements of the consensus of Arab states, however confused a position this may be. Far from formulating policies which the Arab states then adopt, the PLO reflects their will. PLO power is illusory; on its own, it no more influences Middle East politics than does the moon generate light.

The illusion of power is augmented by the fact that, as a symbol of pan-Arabism, the PLO enjoys a special prestige in inter-Arab politics. For this reason, Arab leaders do make efforts to have good relations with the PLO; but these efforts rarely extend to the point of being willing to change policy to accommodate it.

Extremist Ideology. The fact that support for the PLO derived mostly from government had a price. To the extent that the Arab states strengthened the PLO materially, they distorted it politically. Because Arab rulers made the PLO richer and more visible than the scattered and divided Palestinians could have done, its behavior inevitably reflected inter-Arab policies more than Palestinian needs. When conflicts arose, the PLO leaders invariably gave priority to the wishes of Cairo, Amman, Riyadh, Damascus, Baghdad, and Tripoli over the interests of their ostensible constituency. The PLO flourished by becoming an organization answerable to rulers rather than refugees. Neither elected nor in some other manner chosen by the Palestinians at large, Yasir Arafat and his colleagues owed their power more to the interplay of Arab governments than to Palestinian approbation.

Dependent on kings and presidents, the PLO cannot afford to disobey; should it defy any of the six or seven most important Arab states, it can be punished in a variety of ways. The states can cut off funds and arms, deny it safe haven, promote certain member organizations of the PLO at the expense of others, found rival groups, or lobby against the PLO in inter-Arab councils. (Indeed, over the last twenty years every one of these actions has at some time been taken.) Indicative of the pressure Arab states exert is the fact that at the February 1983 meeting of the Palestine National Council, guests (who mostly came from Arab countries) outnumbered official delegates by a margin of 6 to 1. Aware of its vulnerability, the Palestinian leadership invariably adopts policies that will please the maximum number of its patrons. Only apparently free to do as they wish, Yasir Arafat and his colleagues must in fact express the weighted average of what the Arab states demand.

Until now, this average has always translated into an extremist position, namely, the military destruction of Israel. Both its founding document, the Palestine National Charter, and statements by leaders over the years have made it clear that the PLO plans to liquidate Israel through force of arms. To take one example from among hundreds, Yasir Arafat told an Egyptian magazine in very early 1983 that "we have not dropped and we will never drop the military option."

This hard-line policy has remained in place despite all the temptations that have repeatedly been placed before the PLO to recognize Israel's existence. The rewards of such recognition would be great. The United States government, which otherwise refuses to deal with it, would talk to the PLO and thus give it an opportunity to drive a wedge diplomatically between the U.S. and Israel; this would also improve the chances of halting Israeli settlement on the West Bank. Also, recognition would put the PLO in a better position to compete with Syria, Jordan, and Egypt to take over should the Israelis evacuate the Golan Heights, the West Bank, or Gaza.

Recognition of Israel would win enhanced international respectability for the PLO, and support from many countries at present reluctant to sanction the destruction of the Israeli state and people. The importance of this was made clear in January 1983 by Issam Sartawi, an adviser to Yasir Arafat, who stated that "at the top of our priorities is the need for us in the PLO to complete our recognition by the world." Sartawi went on to state that had the PLO enjoyed wider respectability in the summer of 1982, "Israel would have not dared invade Lebanon and announce that its objective was to slaughter us."

Indeed, little would seem to be lost by accepting Israel's existence. The PLO has no sensible hope of defeating Israel militarily, either on its own or with any combination of Arab states. The balance of forces is such that the old Arab dream of driving the Jews into the sea has become pure fantasy - for the foreseeable future, at least. Then why not take the commonsensical step of recognizing Israel? Why does the PLO refuse to compromise?

Western observers sometimes account for this apparently futile and counterproductive strategy by invoking stereotypes. One explanation holds that the Arabs have a tendency to get carried away with words; they confuse rhetoric and reality. According to this, the PLO is a captive of its own fiery speeches about the imminent Palestine revolution. But no one - and certainly not the PLO leadership - is so stupid. Enchantment with words can no better explain the PLO's unrealistic program than can the love of money explain America's wealth; both arguments reverse symptom and cause. Equally unconvincing is the notion that Arabs have a different logic from ours; there is only one logic and everyone shares it. Just because PLO behavior is not self-explanatory does not make it irrational. There are sensible reasons for the apparently counterproductive action of the PLO, and they tie in with the demands of the Arab states.

After the calamitous defeat of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in June 1967, the states retreated into self-interested nationalism, which implied less attention to anti-Zionism and more attention to raison d'êtat. Whereas Gamal Abdel Nasser had earlier used Israel as a means to stir passions across the Arab world, Anwar al-Sadat made peace with Israel for the sake of Egyptian interests. Abdel Nasser saw the destruction of Israel as a vehicle for uniting the Arabs; Sadat viewed the conflict with Israel as a drain on his country's resources. One stressed pan-Arabist dreams, the other Egyptian needs.

Nearly all the other Arab states also abandoned fervent pan-Arabism, though less dramatically than Egypt. In doing so, they passed the mantle to the PLO, which as a revolutionary movement was expected to succeed where hidebound governments had failed. Arab rulers came to rely on the PLO to maintain pan-Arabism; the organization became the symbol of Arab irredentism, leader of the hard-line position, and bearer of the burden thrown off by the states.

Were the PLO to give up the dream of destroying Israel, it too would be putting parochial interests ahead of the good of the entire Arab nation. It is difficult enough for Arab states to take this step. Were the PLO to do so, against the wishes of the states, its position in inter-Arab politics would be destroyed. So long as influential states such as Syria and Libya demand total rejection of Israel by the PLO, the Palestinian leadership can hardly do otherwise.

Thus, to the extent that the cause of the military destruction of Israel provides the PLO with backing from the Arab states, extremism is inherent in its mission.

Inefficacy. The involvement of the Arab states also explains PLO inefficacy; having to become party to inter-Arab disputes distracts attention from its anti-Zionist program. The more the Arab states disagree among themselves, the less power the PLO enjoys. An isolated Syria or a maverick Egypt reduces the pan-Arab consensus that makes the PLO prominent. Just as Israel would have the Arabs at odds, the PLO needs them brought together. But Arab rulers disagree so often that Arafat typically devotes more than half his time to patching up relations among them. Indeed, PLO relations with Arab states have at times soured to badly - armed wars with Jordan and Syria, spy wars with Iraq, cold wars with Egypt and Libya - that these have consumed much of the energy intended for the conflict with Israel.

The PLO has also been kept busy by the whole gamut of Arab enthusiasm and crises, such as Ba'thism, Nasserism, the trauma of 1967, the oil weapon, Egypt's peace with Israel, and the disintegration of Lebanon. It needs to fend off the interference of Arab states in its own designated territory: Syria and Jordan compete with it for control of parts of Palestine, and for nineteen years Egypt administered the Gaza Strip. Indeed, the Syrian government has such strong interests of its own in Palestine that, in the words of a PLO aide, "Syria would love to see Israel wipe out the PLO. If only the political shell of the PLO remains, they will be able to fill it with their own men." Finally, because pan-Arabism has made the Palestinian cause a critical element in the domestic politics of such countries as Iraq, Lebanon, and Libya, that cause has taken on a life of its own in those countries and led to their intimate involvement in PLO affairs. For all these reasons, Palestinian leaders from the Mufti Amin al-Husseini in the 1920s to Yasir Arafat have had to concern themselves no less with inter-Arab affairs than with fighting the Zionists.

After 1967 the PLO had to accept the responsibilities that went with being the conscience, symbol, and pivotal institution of pan-Arabism, even if this meant mobilizing fewer resources for battle against Israel. Pan-Arabist diversions impaired PLO capabilities and help to explain why it fared worse in the military fight against Israel than what its resources should have made possible.

Support from the states also exacts a cost by fostering an unjustified egoism in the leaders of the PLO. On this point they bear a curious resemblance to the shah of Iran, Mohamed Reza Pahlavi. Oil revenues freed the shah from taxing Iranians, and thereby released him from the normal political constraints that accompany the coaxing of money from subjects. Not needing his people's approval, he felt he could do anything he wanted. Seduced by dreams of grandeur, he drafted increasingly splendid plans for Iran which had less and less to do with the wishes of Iranians, until the whole edifice came crashing down. In like fashion, if less grandly, PLO leaders live in a world of their own making; spoiled by easy money from above, they run a guerrilla organization as though it were the decisive factor in Middle East politics., the linchpin of East-West relations, and the key to the oil market. By succumbing to illusions power, the PLO has become as isolated as the shah.

Hated By the Palestinians

Finally, PLO dependence on the Arab states also goes far to explain the paradox of PLO strength internationally and its wretched relations with ordinary Arabs and Palestinians. For the PLO is simultaneously the UN's most popular liberation front and the movement no Arab state wants to host; the toast of radical and Islamic groups around the world but widely resented throughout the Middle East. On the one hand, it enjoys a voice in Arab councils, wealth, vast military supplies, and a claim to be the political voice of the Palestinians. On the other hand, it regularly murders opponents, relies on mercenaries and children to do its fighting, and uses civilians as military cover.

Because meeting the Arab demand for ideological purity counts more than satisfying the interests of Palestinians, the PLO does not pressure Arab governments to enfranchise Palestinian refugees in the various Arab countries in which they have been living since 1948, it does not work to win them citizenship or the right to own land, nor does it take other practical steps to help them alleviate their plight. No wonder a 1980 poll revealed that only half of 1,200 Palestinian students in Kuwait considered the PLO to be their sole representative.

As for the Palestinians on the West Bank, the leaders needed to promote their interests will not be found in the PLO. While a group of mayors on the West Bank prepared a document in December 1982 calling for the "peaceful settlement of the Palestine problem" through the "mutual and simultaneous recognition" of the PLO and Israel, and while in that same month four lecturers from Bir Zeit University stated that most of the students at their university favored territorial compromise with Israel, PLO leaders were reconfirming their intent to destroy Israel militarily. But what do mayors and students matter when heads of state give money, arms, and diplomatic support? Despite the fact that Israel enjoys complete military superiority over the Arabs and will for years to come, despite the daily advance of Israeli settlements on the West Bank, the PLO sticks to its hopeless irredentism. To do otherwise would jeopardize its standing and perhaps even its existence. When a ruler like Muammar al-Qaddafi announces that "If the Palestinian resistance recognizes Israel, we will not do so," this cannot but influence PLO behavior.

Of many examples of PLO brutality toward the Palestinians (on the West Bank, in Gaza, Israel, and Jordan), the most dramatic took place in South Lebanon between 1975 and 1982, where the PLO enjoyed a nearly sovereign authority. As an illustration of its inability to win support from below, developments there repay consideration.

When PLO guerrillas were initially stationed in South Lebanon following the 1967 war, their struggle against Israel enjoyed the sympathy of local Lebanese, especially the Shi'is. Relations between residents and the PLO deteriorated, however, as Israel's overwhelming military superiority dashed hopes of the conflict being moved to Israeli territory. Instead, the PLO settled into South Lebanon. Its troops, better armed and organized than other militias in the area, compelled the Lebanese to supply sustenance, shelter, medical services, and money. By 1975, the PLO constituted an elite that effectively controlled South Lebanon, flouting local regulations and enforcing its will in capricious ways. PLO soldiers billeted themselves in the best houses, grabbed what they fancied, expelled property owners, availed themselves of local women, indulged in random violence, directed drug and prostitution rings, and ran protection rackets. Foreign mercenaries employed by the PLO became especially notorious for extracting whatever they could from South Lebanon, and the PLO's thirty autonomous groups, each with its own loosely disciplined troops, wrought havoc upon the civilian population.

The result was a reign of terror. For seven years the outside world heard little from South Lebanon - in part because the inhabitants feared retribution if they talked, in part because the PLO kept journalists from the region. When its control was broken and newsmen appeared in June 1982, stories of life under the PLO began to filter out. Everyone seemed to have a tale - Muslim and Christian, Sunni and Shi'i, Lebanese and Palestinian - and was eager to tell it.

Appalling accounts of cruelty and malevolence came to light. Any show of defiance of the PLO met severe punishments. A Muslim religious dignitary in Haruf, Sa'id Badr ad-Din, who refused to incorporate Palestinian themes into his weekly sermons, lost his son, murdered by the PLO. Mahmud al-Masri, a Shi'i religious leader in Ansar, led the opposition to PLO entry into the village in 1980; he was tied up and forced to witness the rape, execution, and mutilation of his fifteen-year old daughter. On October 19, 1976, about 1,000 PLO troops stormed Ayshiyeh, a small Christian village whose citizens were suspected of cooperation with Israel; the PLO forced all but 65 of the villagers into a church, guarding them with cocked guns while those outside were systematically executed in the streets. The villagers held in the church heard the whole massacre; when let out after two days, they found the bodies lying in pools of blood. To compound its cruelty, the PLO brought a fleet of trucks to the village and emptied the houses during those two days. After the residents buried the dead, all but a few abandoned their homes.

To maintain its reputation, the PLO acted with calculated ferocity. When a search squad in Sidon turned up Israeli money and clothing in a man's house, the PLO took the owner to Sidon's central square, chained his arms and legs to the bumpers of four cars, and ripped him apart; while the body was yet in its death throes the four cars dragged it around the square. Witnesses testified to the sadistic torture carried out at the PLO prison in Sidon, a former municipal school whose basements became notorious. Above its dungeons was an "entertainment center" for the prison commanders, consisting of an iron bed under Stars of David drawn in blood, used for gang rapes. Although the screams of young girls cold be heard all over the district, no one dared intervene. Unverified reports had it that when PLO hospital blood reserves ran low, new supplies were obtained by bleeding civilian patients to death. And so on: as the local population became intimidated by such atrocities, no one dared challenge the PLO.

Lebanese authorities stood helplessly by. In the words of Khalil Shamrayya, a shopkeeper in Sidon, "Arafat's gangs simply eliminated the rule of law and order and allowed sheer anarchy to reign." Police and politicians reported to work as usual, but handled only municipal services and other matters disdained by the PLO. As "People's Committees" replaced courts, elected Lebanese officials saluted PLO officers and violence went unpunished. "Ultimate authority was with the Kalashnikov [the Soviet gun] and they had it," observed a prominent Sidon doctor, Ramzi Shabb.

Unable to fight the Israeli army on equal terms, the PLO protected itself with the lives of innocent Lebanese, using civilian facilities - homes, churches, schools, hospitals especially - as shields against Israeli retaliation. Even the Roman ruins at Tyre were converted into a military base, with weapons stored in the seats of the hippodrome. When PLO missiles hit the Galilee, civilians in South Lebanon paid the greatest price, for Israel responded with tenfold punishment. A bitter joke has it that a sheikh once went over to the PLO fighters camped near his village and requested that they fire their rockets at his village rather than into Israel. Mystified, the PLO leader asked the reason; the Lebanese replied, "Every time you shoot three rockets at Israel, they fire back twenty; so do us a favor and shoot at us directly!" In what came to be known as the "last massacre" during the Israeli advance of June 1982, PLO fighters deliberately brought down maximum destruction in South Lebanon, provoking the Israelis into bombing anti-PLO villages (such as Burg-Bahal) by taking up military positions as close to them as possible.

The Lebanese were also harmed economically. A backward region, South Lebanon could not cope with the large sums of money the PLO dispensed. Severe inflation which began in the mid-70s cut into the real earnings of laborers and reduced the value of savings. It also made working for the PLO, with its high wages, more attractive.

Even Palestinians, who should have benefited from the activities of the PLO, were victimized, as the PLO's constant problems with recruitment demonstrate. Any male Palestinian in Lebanon could receive $150 to $200 a month - as much as an agricultural worker - just for joining a PLO militia; then he had only to train briefly in the use of weapons, participate in parades, and show up for an occasional operation. In addition, his wife got $130 a month plus a small amount for each child. Yet these high wages were not enough, even in combination with a shortage of employment and ideological fervor. So alienated were Palestinians living in Lebanon from the PLO that it had to take active measures to recruit sufficient numbers of soldiers; characteristically, it resorted to coercion. The PLO enjoyed the enthusiastic support of over twenty Arab states, two dozen other Muslim countries, most of Africa, and the Communist bloc, but it could not attract Palestinian men to fight for its cause.

In 1968, Muhammad 'Abd al-Ghani, a thirty-year-old assistant pharmacist, received a letter from Yasir Arafat threatening to expel him from his home and job unless he joined Fatah. Fearing for his life ("If I stay, they may kill me"), he joined As-Sa'iqa, one of Fatih's rival organizations within the PLO, becoming a recruiting agent until an opportunity arose to drop out, which he did. Although rounded up by the Israelis last summer and held in a camp, he said he was pleased with the destruction of the PLO in Lebanon. Now, "they will never catch me. There will be no more Yasir Arafat."

The cover of an Ashbal magazine from 1970. |

Palestinians who left the refugee camps hoping to become integrated into Lebanese society were harassed, forced either to serve in the Palestine Liberation Army or to buy their way out of duty. Several thousand mercenaries from a dozen or so countries, including the Arab states, Senegal, Turkey, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, took their money and replaced them in the field. Indian mercenaries in Lebanon in the fall of 1981 numbered nearly 1,000; according to a magazine investigation, most of them took up military service when they failed to get other work (they had entered Lebanon illegally), and they earned about $200 a month. So desperate was the PLO for fighters, it paid Lebanese beggar boys like young Haysam Muhammad Rabi'a $250 to enlist in the infantry. But such recruits made poor soldiers; Haysam was captured by Phalange troops in June 1982 as his unit attacked the town of Bhamdam while in a drugged and drunken condition.

The PLO's response to the Israeli invasion in the summer of 1982 illustrated the way its leaders distinguished their own interests from the Palestinians' as a whole. At a critical time in July, as the city of Beirut ran short of food supplies, the PLO commandeered a United Nations warehouse in West Beirut, blocking the distribution of flour, rice, sugar, corn beef, and milk powder to 30,000 Palestinians, including many homeless families from South Lebanon. Worse yet, according to Sa'd Milham, a seventy-eight-year-old Palestinian, the PLO used Palestinian civilians - their own people - as cannon fodder. When inhabitants of the Ein Hilwe refugee camp in Sidon took shelter in a mosque, the fighters pushed them outside to draw Israeli fire; those who refused to cooperate were shot at in the mosque. On a larger scale, the PLO used the entire civilian population of West Beirut as a shield, letting non-combatants suffer the worst casualties and hoping that civilian deaths would so upset world opinion the Israelis would be compelled to call off their siege.

The PLO as Dictatorship

Assessments of the PLO are often confused by the fact that it provides services to Palestinians, employs them, and even sometimes protects them. Can an organization that performs all these functions really be so harmful to its own people?

To understand this better, it is helpful to view the PLO as a government rather than as a guerrilla organization, for its behavior resembles that of "progressive" regimes in the Middle East far more closely than that of other "liberation movements." Certainly, PLO treatment of civilians in South Lebanon makes it unique among guerrilla groups: Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwean forces terrorized white Rhodesians but not the Zambians among whom for years they lived, and the Sandinistas did not harm Nicaragua's neighboring peoples. The Communist movement in China, the FLN in Algeria, and for that matter Menachem Begin's Irgun would have collapsed had they treated their own people as does the PLO.

The PLO can act as it does because it does not depend on support from below; so long as it satisfies the Arab rulers, it monopolizes the Palestinian national movement and can behave as an established government. The qualities it displays - disproportionate involvement in international politics, ideological extremism, grandiose ambitions, brutality - are the hallmarks of most Middle Eastern regimes; they are especially characteristic of the oil-exporting states which, like the PLO, live off money from outside sources. They, like the PLO, do provide basic services and do build economically - even as they threaten their people with force and intimidation. The Syrian authorities conquered their own city of Hama in early 1982 at the expense of thousands of civilian lives (estimates of the death toll vary between 3,000 to 25,000). The Sunni rulers of Iraq wage war on the Kurds and repress the Shi'is. South Yemen lives in a darkness so complete the outside world knows almost nothing about it. Qaddafi has turned Libya into a maelstrom.

In short, the PLO's acts of violence against its own people - grenades against laborers seeking work in Israel, bullets for those on the West Bank and Gaza who disagree with its policies, truncheons for those living in the camps - closely resemble the policies of the governments that champion it most fervently. Remove the framework of a "liberation movement," and what remains is the sort of dictatorial regime all too familiar in the Middle East. Only the fact that the PLO does not rule a territory endows it with the aura of romance lacking in "progressive" states already in power. But the PLO's record should make its character clear enough. Like other radical movements, this organization appeals to two groups primarily - the elite that it benefits and the distant admirers who stay far enough away to avoid the consequences.

Implications

Recognizing the critical role of Arab help has several implications for Middle East politics. First, it means that the PLO has very little of the political power so often ascribed to it. The PLO may appear to shape the policy of most Arab states, but in fact it reflects their wishes. It brings up the rear, echoing and rephrasing the weighted average of Arab sentiments. This suggests that it will moderate only when its Arab patrons want it to; so long as the Arab consensus needs it to reject Israel, the PLO must do so. Aspiring peacemakers in the Middle East must therefore not make settlement of the Arab-Israeli dispute contingent on PLO concurrence, for this is to give a veto to the organization least prone to compromise.

Second, while Arab rulers make the PLO rich and prominent, they also prevent it from becoming a representative body, an effective one, or a decent one. So long as it exists, the PLO will continue to ill-serve Palestinians by subordinating their interests to those of Qaddafi, Fahd, Assad, and Saddam Hussein. Do the Palestinians have an alternative to the PLO? Can they develop their own institutions, independent of the Arab states, which would cast off the PLO's illusory ambitions, discard its autocratic structure, accommodate Israel's existence, and promote practical interests? The "New Palestinian Movement" reportedly organized last fall in South Lebanon, the attempt of Palestinians living in the West to organize politically, or the efforts of West Bank mayors are moves in this direction. But their hopes of success must be slim, for no fledgling refugee organization has much chance against the weight of Arab consensus, which is still vested in the PLO.

Third, only the Arab states - and not Israel - can kill the PLO. By itself, Israeli force of arms, no matter how overwhelming, cannot crush this symbol of pan-Arabism; the PLO will last so long as it serves a purpose for the Arab states. The key Arab states (Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia) will join Egypt in recognizing Israel only when they have enough confidence in their own rule to dispense with hostility to Israel as a source of legitimacy; or when, as in Egypt, the endless futility of anti-Zionism makes it more of a political liability than a benefit. At that moment the PLO will lose both its support and its raison d'être.

Daniel Pipes, a Council on Foreign Relations fellow, is the author of Slave Soldiers and Islam (Yale University Press). His new book In the Path of God: Islam and Political Power, will be published by Basic Books in the fall.

June 11, 2022 update: I wrote this note to Mark Wortman, author of the just-published book, Admiral Hyman Rickover: Engineer of Power:

Mr Wortman:

I just read the interview with you in the Times of Israel and thought I'd tell you about my experience with Adm. Rickover.

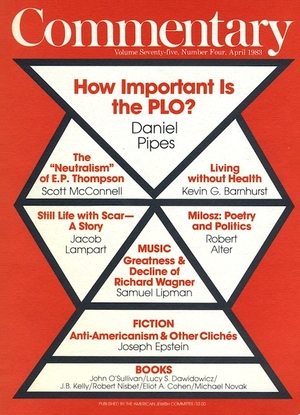

It was April 1983, I was working the State Department, and an article of mine had just appeared in Commentary magazine: https://www.danielpipes.org/documents/165.pdf.

The article received a fair amount of attention. See, for example, https://www.nytimes.com/1983/04/17/opinion/the-jordan-door-slams-shut.html.

The admiral called me out of the blue at the office and proceeded unceremoniously to chew me out for my completely misunderstanding the nature of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

Almost 40 years later, I hardly remember the specifics of his critique, but it was a unique moment in my career, having someone of his stature telephone me to give me a gratuitous verbal whipping.

Yours sincerely,

Daniel Pipes