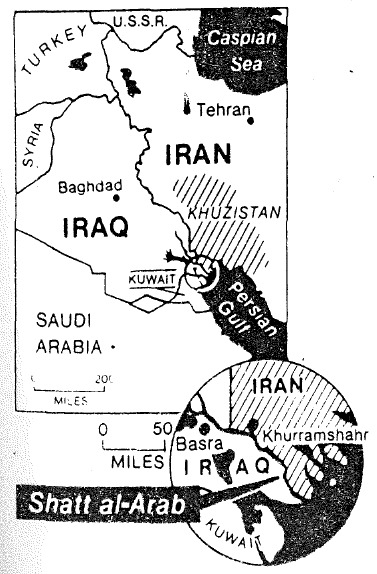

For over 50 years, one issue has prevented Iraq and Iran from enjoying good relations; Control of the Shatt Al-Arab waterway. This is the object of their current fighting. Shatt Al-Arab is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at the south if Iraq, about 100 miles from the Persian Gulf. It is a river of charm and exotic beauty, home of Sinbad the Sailor and the marsh Arabs. Its importance today arises from the fact that its final 40 miles mark the border between Iraq and Iran.

Two Justifications

WSJ map accompanying this article. |

There the matter rested for several decades, though the Iranians did not like the fact that their two key ports of Abadan and Khurramshahr could be reached only through Iraqi waters. In 1965, Iranian oil-loading facilities were moved from Abadan to a site in the Persian Gulf, Kharq Island, to stall further Iraqi meddling. But still, trade to Khurramshahr, through which most imports to Iran came, was subject to Iraqi interference; moreover, heavy-handed Iraqi officials made use of the Shatt Al-Arab waterway increasingly unpleasant for Iranians. Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi threatened in 1965 to renounce the 1937 treaty if Iraqi provocations continued, and in 1969 he did so, demanding a new border along the median line of the river.

To pressure Iraq into agreement, the shah aided Kurdish rebels in northern Iraq, supplying them with arms, money and sanctuary. The tactic worked; in March 1975, the Iraqis agreed to a new border down the middle of the Shatt Al-Arab in return for cessation of Iranian support for the Kurds. The Kurdish movement collapsed within months.

This 1975 agreement won internal peace for Iraq but at a cost of bitter, vengeful feelings among the Iraqi leadership. The ruling Baath Party pays enormous attention to the integrity of the "Arab nation" and the sacredness of its land. Allowing even half a river 40 miles long to fall under the control of Iran rankles deeply. The Iraqi rulers accepted the changes in the waterway temporarily in order to purchase peace with the Kurds, but they hoped eventually to win back all they had conceded.

The opportunity to do so came more quickly than they may have expected – the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1978 – 79 overturned the balance of power.

The fall of the shah and his replacement by Ayatollah Khomeini led to intense animosity between the two countries. Khomeini's policies also caused the collapse of Iranian military power. Iran's new leaders fomented trouble among Iraqi Shi'is, calling for Muslims in Iraq to overthrow their "atheistic" rulers. The Iraqis, in turn, have aided many enemies of Khomeini's regime – Shahpur Bakhtair, General Oveissi, a movement seeking independence of Khuzustan, and Kurdish rebels. Gunman from Iraq attacked the Iranian embassy in London at the end of April.

As the shah's massive military machine fell apart, Iran became an increasingly tempting target. Troops deserted, officers were purged, foreign technicians fled. A ban on weapon sales to Iran by the U.S. after the embassy seizure forced cannibalization of aircraft for spare parts. Civil war and sabotage have been widespread. Military expenditures are only a fraction of what they once were, and the military has declined from its lofty status under the shah to a suspect organization with severe morale problems.

Given the hostile Iraqi feelings about the 1975 accord and the impotent aggressiveness of Khomeini's regime, it was only a matter of time until the Iraqis would renounce the 1975 agreement and claim jurisdiction again over more than half of the Shatt Al-Arab. They did so last week. It was also clear that they would probably go beyond this to control more Iranian territory, in particular the province of Khuzistan.

Khuzistan is the southwestern region of Iran, and borders Shatt Al-Arab. It has two qualities that make it unique in Iran: It contains virtually all Iran's oil reserves and until recently a majority of its populace spoke Arabic.

Until 1938, the area was known as Arabistan. The Arab element gives the Iraqis a justification for meddling and possibly even for laying claim to the oil-rich province. In addition, Khuzistan's fine ports would provide Iraq with much-needed deep-water harbors.

The Iran war supports Saddam Hussein's ambitions. |

For Iranian politics, the implications of war with Iraq look much less pleasant. It must be remembered, however, that Iran is still consumed by its revolution and events there follow a logic of their own. Of the two parties contending for power in Iran, the nationalists and the activist Muslims (represented by Bani Sadr and Mohammed Beheshti, leader of the Islamic Republican Party), the latter seems to be winning. Its first concern does not lie with the Shatt Al-Arab waterway, the Iranian armed forces or national unity. Rather, it is trying to transform Iranian life along Islamic lines. Consequently the government's concerns recently have mostly had do to with culture and morality. Iran fell into war with Iraq due to emotional fervor and preoccupation with domestic matters, not for reasons of calculated gain. Iran escalated the war by bombing Baghdad and Iraqi oil installations out of desperation, not as a result of a clear battle plan.

There is very small chance that the war with Iraq will lead to release of the American hostages. Quite the contrary. On Tuesday the Majlis (Iranian parliament) shelved the hostage issue indefinitely. That action may have come in response to a very clever Iraqi move the day before. Baghdad Radio announced that the hostages had been freed and pointed to this as proof that the Iranian government is in collusion with the CIA. In fact, the Iraqis fear that if the hostages are released Iran will make peace with the U.S. and receive the spare parts it so desperately needs. This false announcement from Baghdad makes a reconciliation much more remote; the Khomeinists would never allow themselves to be out-anti-Americaned so easily.

Prolonged Captivity

The United States stands to gain little. The war will probably prolong the hostages' captivity and it will certainly disrupt oil supplies for ourselves and our allies. An Iraqi victory will increase the influence of a radical state that execrates the Camp David accords, threatens stability in the Middle East and increasingly supports revolution around the world.

Moreover, an Iraqi victory is a Soviet victory; the Russians supplied most of their arms and are now in the position to tighten their hold over Iraq. An Iraqi success boosts the standing of the Soviet Union internationally while making the Baath regime more vulnerable to Soviet pressure.

Our first concern now is not which of these anti-American states wins but that oil shipments leave the Persian Gulf with as little disruption as possible. To assure that, the U.S. may have to position warships at the Straits of Hormuz to guarantee the trade lane leading into the gulf.

Beyond that the U.S. has few options; the Russians hold nearly all the cards. An Iranian defeat in this war will open that country to further divisions and make it ever more susceptible to Soviet intrigues.

Mr. Pipes, an Islamic historian at the 'University of Chicago, is writing a book on the role of Islam in recent world politics.