The war between Iraq and Iran has renewed Washington's hopes for the release of the 52 American hostages being held in Tehran. Even before Iran's military deficiencies had become apparent in the battles over its oil ports, President Carter hinted that the United States might resume shipping military spare parts and other aid upon the hostages' release.

This tactic would appear to make sense; the Iranians certainly need all the help they can get. Why wouldn't the prospect of military assistance lure them into ending the hostage crisis?

Unfortunately, Carter's hope ignores the realities of political life in Iran. The challenges of the war have probably lessened the likelihood of early release of the captives, for both the war and the hostage drama are being played out in the context of Iranian politics, a world unfamiliar, and normally of little concern, to Americans.

But Iranian politics is worth learning about in order to comprehend why the hostages were taken in the first place, why they are still in captivity, and what must happen before they are let go.

The key fact about politics in Iran today is that two distinct factions came to power with the success of the Islamic revolution: nationalists and activist Muslims. Although they agree on general goals (especially the vital importance of Iranian national independence and the restructuring of Iranian society along Islamic lines), the primary concerns of the two sides differ. Simply put, while the nationalists stress Iran, the activist Muslims stress Islam. The nationalists want to remake social and economic life, whereas the activist Muslims are most concerned with cultural and moral matters.

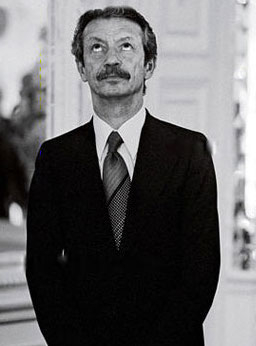

Shapour Bakhtiar, the shah's last prime minister, tried to stay on under Khomeini but failed. |

Activist Muslims know much less about modern culture or the West and wish to remain ignorant. Few of these men have left Iran or speak foreign languages; they learn about Western ideas only second hand through Persian or Arabic writings. To them, the West looms large as a source of wickedness and the United States presents Iran's greatest danger. In their eyes, not only did the United States rule Iran for 25 years after 1953, but Washington is still trying to overthrow the regime of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini; worse, they see American culture as the key corrupting element in Iranian life.

In the 20 months since Khomeini returned to Iran, nationalist and activist Muslims have battled for control of the country. They fight in the streets, control rival armed forces, argue on the airwaves and in the press, debate in Parliament, and conspire in Khomeini's reception rooms. Equipped with a vision of Iran's future, each faction hopes to impose its ideals on the rest of the country. The battle for Iran is on; will it maintain links to the modern world or will it turn away in the attempt to recreate traditional patterns of life?

Put another way, will Iran have one revolution or two? Nationalists prefer to call it quits at just one, the political overthrow of the shah; now they want to return to business as usual. But activist Muslims insist on a second revolution, a social, economic and cultural upheaval directed toward creating an Islamic order. To attain their goals, the activist Muslims were determined to take control of the government into their own hands; one by one, the non-mullahs have been excluded from power by members of Ayatollah Mohammed Beheshti's Islamic Republican Party.

This process was considerably helped by the embassy seizure, for holding the hostages strengthens the hand of the extremist Muslim elements against the nationalists. Keeping guard over the Americans bestows startling power on motley students and rabble-rousers, power they have kept now for nearly a year. They issue frequent declarations denouncing the nationalists, and these are aired on national television; mobs rally quickly to their defense; and relations with Washington cannot improve unless the activist Muslims allow it.

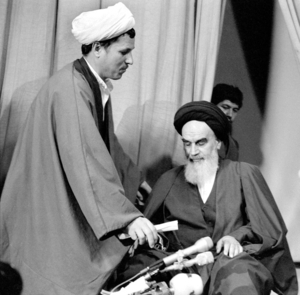

Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (L) with Ayatollah Khomeini immediately after their return to Iran in February 1979. |

The activist Muslims who are now nearly in control of Iran, have domestic priorities even more important than defeating Iraq. For this reason, American attempts to pry the hostages free will continue to be futile. No pressures or gestures – economic or political, threatening or cajoling – will impel the activist Muslims into releasing their precious American booty until doing so serves their needs – their domestic needs. The best strategy for America, in the face of Iranian politics, is either to say nothing or to do something forceful: bluster or apology will get Washington nowhere.

Daniel Pipes, a historian at the University of Chicago, specializes in Middle Eastern and Islamic affairs. He is writing a book on the role of Islam in current politics and the ramifications of the oil boom of the 1970s.