Daniel Pipes

There is a mood of student conservatism but it is not growing; today's students concern themselves far more with entering the established order than with changing it. But this mood does not represent a backlash against the activism of fifteen years ago; to the contrary, it signals a return to normality, for the historical record shows that American university students usually involve themselves very little in politics – far less than their peers in other countries.

Thus, 1960s radicalism, and not the recent quietism, is exceptional and requires explanation. College students born in the "baby boom" years after World War II grew up in a period of unique economic growth, world power and patriotic idealism in America: as a result, they came to assume financial well-being for themselves, their country's prowess, and – something often overlooked – the possibility of implementing the ideals taught them as children.

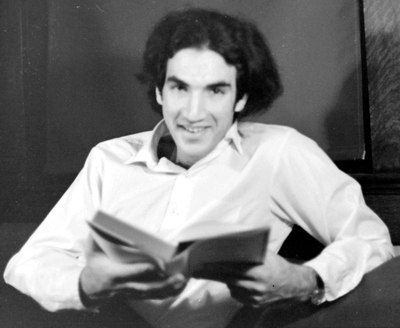

The author as a studious undergraduate. |

On reaching college, they looked around and found the United States to be much less perfect than what they had come to expect. Disappointed but fervently idealistic, the students tried to make their country as good as its claims. Obsessed with what was wrong, the activists became blind to the enormous achievements of the country (enormous relative to other places, paltry compared to the ideals). Unrealistic and impatient, they wanted radical improvement, regardless of feasibility. Eventually they burnt out, exhausted from idealism.

Today's students grew up in more sober times: economic stagnation began when they were children, American power declined about the same time, and the high ideals of the post – war period fractured. In short, normal conditions returned. Students responded by reverting to the pragmatic and personally ambitious goals which have characterized most of the preceding student generations.

By now, there is much facile nostalgia for the heady days of the late 1960s; those around then recall the excitement, those too young regret the dullness that has taken its place. But those were serious disturbances which harmed the universities, created social tensions, and caused loss of property and life. Duller it may be, but when students resumed their standard behavior, it benefited both them and society as a whole.

It may not be tactful to write this in a student journal, but I am on record saying the same when I was an undergraduate; college students rarely have the worldly experience, the savvy, to devote themselves to political causes which make much sense. Their mixture of idealism, lack of responsibility and rebelliousness usually leads to unrealistic programs; better to spend the college years studying and playing.