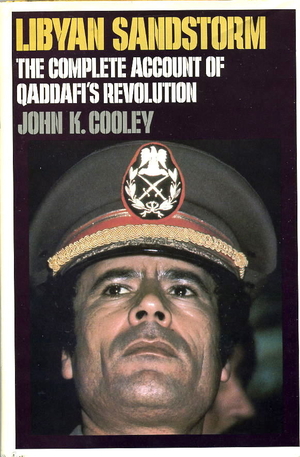

From the moment he came to power in September 1969, Muammar al-Qadhafi has mounted a sustained challenge to America and its world-wide interests. As John K. Cooley shows in Libyan Sandstorm (Holt, Rinehart & Winston. 320 pages, $16.50), within a year of Qadhafi's taking power, he expelled U.S. and British forces from Libya, acquired Soviet tanks, engaged East Germany security forces, tried to buy a nuclear weapon from the Chinese, and broke contacts with the (predominantly American) oil companies operating in Libya.

From the moment he came to power in September 1969, Muammar al-Qadhafi has mounted a sustained challenge to America and its world-wide interests. As John K. Cooley shows in Libyan Sandstorm (Holt, Rinehart & Winston. 320 pages, $16.50), within a year of Qadhafi's taking power, he expelled U.S. and British forces from Libya, acquired Soviet tanks, engaged East Germany security forces, tried to buy a nuclear weapon from the Chinese, and broke contacts with the (predominantly American) oil companies operating in Libya.

Subsequent Libyan actions remained no less hostile, including enthusiastic patronage of international terrorism, subversion of pro-Western Arab governments, and armed aggression against almost all neighbors.

Despite the persistence of anti-American actions – a full record of which takes up most of Libyan Sandstorm – the U.S. not only tolerated Qadhafi but protected him. Mr. Cooley's research establishes a starting but indisputable pattern of American efforts to keep Qadhafi in power. Consider the following:

In November 1969, Qadhafi suspected two Libyan ministers of plans to overthrow his government; in early December, a CIA agent in Libya "warned Qadhafi that there was indeed a conspiracy brewing against him" and confirmed the names of its leaders. The ministers were arrested within a few days and imprisoned.

In mid-1970, "the CIA, working with British and Italian services, thwarted an elaborate, well-planned plot to assassinate Qadhafi. Libyan opposition leaders had hired mercenaries to land on the coast near Tripoli, then to free political prisoners from Libya's main prison, arm them, and dispatch them to attack Qadhafi's residence in nearby barracks. Code-named "the Hilton assignment" this operation was foiled at least three times by Western police, and it eventually collapsed. According to Mr. Cooley, the conspirators concluded that "the United States, Britain and Italy were all hostile to the Hilton assignment, and might go to any lengths to keep Qadhafi out of harm's way."

About the same time, the CIA dissuaded the Israelis from supporting an opposition group planning to attack Qadhafi from a base in Chad. When Qadhafi began to squeeze the American oil companies in September 1970, they needed their government's aid to unite and withstand his pressure; but "the U.S. State Department was not inclined to take a strong stand in support of the American companies, feeling that existing good relations with Qadhafi ... ought to be preserved" – and the companies' position soon collapsed.

In later years, the CIA gave Edwin Wilson and Frank Terpil virtual free reign to run guns and recruit agents for service in Libya. The White House took a benign view on Billy Carter's relations with Libyans: on one occasion, Rosalynn Carter asked him to intercede with the Libyans top representatives in Washington to a meeting in the White House, as late as May 1981, after many years of public concern about Libyan efforts to acquire an atomic bomb, a U.S. government survey showed that 3,000 out of 4,000 Libyans students in the United States were learning nuclear physics!

John Cooley documents but does not explain why the U.S. responded to Libyan provocations with such astonishing timidity. But herein lies a key to American actions in the Middle East; and the two factors behind this pro-Libyan stance – Islam and oil – continue to distort U.S. policy in the area.

Qadhafi's emphatic Islamic orientation lulled Americans into thinking that he had to be anti-Communist and anti-Soviet; but it should be clear that no religious faith, Islamic or otherwise, determines political orientation, much less a country's relations with the great powers. Despite massive evidence to the contrary – starting with Soviet tanks and East German advisers in 1970 – a blind belief persisted until late 1977 that Qadhafi would someday forward Western interests against the Soviet bloc.

Second, Libya's oil exports twisted American policy, as profits ran roughshod over security needs and moral concerns. There is at present no truer test of a nation's foreign policy than its ability to maintain principled relations with the oil states. Compared to many other countries the U.S. has done well, but not well enough to maintain its integrity; time and again, the lure of easy money overwhelmed other considerations.

The strength of Libyan Sandstorm lies in its documentation of Qadhafi's frenetic reign; its weakness lies in Mr. Cooley's unwillingness to draw conclusions and in his carelessness. After 25 full pages about Libya as "Terror, Inc.," he concludes on this meek note: "On Muammar al-Qadhafi and his final place in the history of world terrorism and guerrilla warfare, the final verdict is not yet in."

A casual disregard for detail pervades the book: misspellings, mistranslations, wrong dates, wrong facts, and lapses of logic around. Three times, for example, the dates of the start of the Yom Kippur war in 1973 is mistaken. Also distressing is Mr. Cooley's occasional tendency to lapse into chaotic presentations of unconnected facts.

These reservations aside, Mr. Cooley has written the fullest account of Libyan history in the age of Qadhafi and provided important insights into American foreign policy in the age of oil.

Daniel Pipes is an International Affairs Fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations.