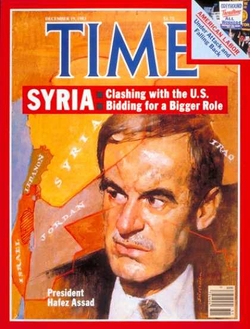

Hafiz al-Asad on the cover of Time magazine, Dec. 19, 1983. |

Since 1979, the Syrian government has blocked relations between the Arabs and Israel because this boosts its domestic and international standing. Damascus actively led the opposition to Egypt's peace treaty in 1979, worked against Jordanian acceptance of the Reagan plan in 1982-83, split the PLO in 1983 when Arafat showed interest in negotiations, and forced the Lebanese government to abrogate the May 1983 agreement.

Syria makes its opposition to Jordanian negotiations with Israel very clear. It has already vowed "to use all forms of struggle to confront [the Jordanian] regime's policy" and threatens to replace King Hussein with a "progressive" government.

Damascus could achieve so much because it possesses powerful instruments of influence. Advanced Soviet materiel makes its armed forces stronger than any Arab rival's and its close relations with Moscow mean it can count on Soviet backing. Syrian sponsorship of a rump PLO gives Asad a vehicle for rejecting negotiations with Israel, while Palestinian forces do his dirty work. Alliances with Libya and Iran place Syria at the heart of a radical anti-American triad. In conjunction with all the above, Damascus sponsors a large proportion of Middle East terrorism.

Arab leaders who disagree with Asad's policies know that he is brilliant and ruthless. In recent years he has destroyed Hama, a rebellious Syrian city, and subjugated two-thirds of Lebanon. Most important, the Syrian government assassinates its enemies, including Kemal Jumblatt, the Druze chief; Bashir Gemayel, president-elect of Lebanon; and Issam Sartawi, the PLO softliner.

How can King Hussein and Arafat stand up to such power? Jordan's monarchy is fragile, its armed forces small, its population fractured. Hussein long ago learned to suppress his desire for accommodation with Israel in deference to Syrian wishes. Yasir Arafat is even weaker. The Palestine Liberation Organization is divided, it lacks an autonomous base, and it just took another severe battering in Beirut. While Jordan and the PLO gain strength acting together, they cannot defy Damascus on an issue so central as the conflict with Israel.

The active support of other Arab states does not balance Syrian power. Egypt lost clout when it opted out of the conflict with Israel; a Lebanese government no longer exists; Iraq is consumed in war with Iran; Saudi Arabian influence declines in step with its oil revenues.

Even with plus the backing of all these states, plus Israel and America, it is of all these it is still doubtful whether King Hussein could resist Syrian pressures. Were he to sign with Israel, Syria and its allies - Iran, Libya, the rejectionist PLO, the Soviet Union - would exert a variety of pressures on Jordan to renege. They might incite Palestinians in Jordan to revolt, deploy terrorists against Jordanian officials, harass Jordan's northern border, and plot coups d'etat. However attractive the prospect of agreement between Jordan, the PLO, and Israel, this venture entails serious risks for King Hussein, and endangers one of the few consistently pro- Western Arab rulers.

Attempting to solve the Arab-Israeli conflict with Jordan is like ending the nuclear arms race by reaching an agreement with Yugoslavia. To be sure, Belgrade is friendlier than Moscow and more susceptible to American influence; but it does not make decisions on nuclear weapons and cannot end the arms race. Likewise, Jordan does not determine the Arab position on war and peace. Only one relationship decisively affects the Arab-Israeli dispute: that between Syria and Israel. Syrian unwillingness to accept Israel's existence perpetuates strife; conversely, were Syria to follow Israel's other three neighbors and resign itself to Israel's existence, the conflict would rapidly come to an end. Real progress requires a change in policy not by Jordan or the PLO, but by Syria.

Daniel Pipes is associate professor at the Naval War College, and the author, most recently, of In the Path of God: Islam and Political Power.