The misty ambiguity of words presents a major obstacle to grasping the history and politics of the Middle East. Geography, peoples, and cultures of the area are hidden by terms used in unfamiliar and inconsistent ways. Accordingly, four key terms are taken up in the following pages; with each, I attempt (1) to sketch the different ways it is used and (2) to propose a practical, common-sense definition for it.

The misty ambiguity of words presents a major obstacle to grasping the history and politics of the Middle East. Geography, peoples, and cultures of the area are hidden by terms used in unfamiliar and inconsistent ways. Accordingly, four key terms are taken up in the following pages; with each, I attempt (1) to sketch the different ways it is used and (2) to propose a practical, common-sense definition for it.

The Middle East. British colonial administrators coined this term just before 1900 to refer to regions of the British Empire which lay between the Near and Far Easts, between the Levant and East Asia. The India Office administered this area; when the British left India and the India Office closed its doors, the Middle East lost its precise, administrative definition and passed into common speech as, vaguely, an area centered in southwest Asia. "Near East" and "Middle East" lost their distinctiveness and conflated into a single meaning, so that today the two terms are virtually identical.

As a geographic term, "Middle East" is not a happy phrase; it betrays a Eurocentric bias out of keeping with today's realities; on a map of Eurasia, this region is not in the middle east but in the middle west. But it has by now gained widespread recognition in the titles of countless institutes, journals, book titles and government offices. Also, it has been adopted not only in nearly every language used outside the Middle East, but also in the languages of that region (Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Kurdish, Armenian, Assyrian, etc.). Despite its inaccuracy, the "Middle East" is here to stay; we therefore need an exact definition for it.

My own informal survey shows that no two persons agree on the precise boundaries of the Middle East. Some extend it as far as Mauritania in the west and India in the east, from the Balkans and Central Asia in the north to the Horn of Africa in the south. At the other extreme, some narrow the region down to the Fertile Crescent (Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan), the Arabian Peninsula, and Egypt.

Choosing sensible borders for the Middle East requires first that one define what wields the area together as a unit – its ecology and culture. Although any definition of the Middle East produces an ungainly and misshapen area, lacking geographic coherence, it does have common ecological elements: all of it lies in the hot arid zone. As a result, certain features are found through much of the area: deserts, camels, oases, and oil deposits. The Middle East also has cultural characteristics which come readily to mind: Islam, a multiplicity of minorities, suqs, veiled women, harems, famous hospitality, coffee drinking, and so forth.

A sensible, if small, definition of the Middle East. |

More important, this area has always formed a single large cultural unit, from the most ancient times until the present, a period of some five thousand years. Its history divides into three long eras: the ancient, the Greco-Roman, and the Islamic. In the earliest period, the whole Middle East shared in the civilization which first developed in and then spread from Mesopotamia to Egypt. In the Greco-Roman period, it was the area conquered by Alexander the Great: for centuries, the Middle East came under strong Hellenistic influences.[2] In Islamic times, the Middle East constitutes the heartland of Islam, an area in which Islam has had the longest and most pervasive influence and in which Muslims make up the overwhelming majority of the population.

Arabs. By "Arabs" three different groups are meant; Arabic-speaking peoples who live (1) in Arabia, (2) the Middle East, or (3) anywhere.[3] These three categories are invariably confused and used indiscriminately.

The first kind of Arab lives either himself in the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula (in Saudi Arabia, Oman, the Persian Gulf statelets, or the Yemens) or lives elsewhere but traces his ancestry to there. The Arabic language developed in Arabia; its inhabitants have been called "Arabs" for thousands of years. Although the English word "Arab" closely resembles the word used in Arabic for these people, 'arab, English also has a clearer and more specific term for them: Arabian. Much less ambiguous than "Arab," Arabian should be used to refer to the peoples of the peninsula; they number about twelve million persons.

A second meaning of "Arab" includes both Arabians and Arabic speakers in adjacent countries – the Fertile Crescent, the Yemen, and sometimes Egypt. If Egypt is included, this embraces all the Arabic speakers of the Middle East,[4] who number about eighty million (forty-two million without Egypt).

Lastly, "Arab" is used to refer to Arabic speakers everywhere, both in the Middle East and in northern Africa. In Africa, they predominate in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt; they are also numerous in Mauritania, the Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia. All the Arabic speakers together number about 140 million persons.

Even in this widest definition, not every Arabic speaker is known as an Arab. Members of minority groups sometimes identify more with their group than with the Arabic language; these include Arabic speaking Jews, Druse and Baha'is. A more exact definition of the third meaning might read: a native Arabic speaking Muslim or Christian.

These three types of Arab fill lopsided concentric areas: (1) Arabia; (2) Arabia, the Fertile Crescent, and possibly Egypt; (3) Arabia, the Fertile Crescent, and the northern third of Africa. Caveat emptor: in speech and in writing, the various meanings of Arab are used without definition and sometimes interchangeably; it is important to ascertain which group the word refers to.

How did such three parallel but distinct meanings evolve? Arab as Arabian is the original usage, ancient and indigenous; the other two usages are more recent and require an explanation. Both terms date back about a century, to the first stirrings of Arab nationalism. The concept of an Arab people – a people bound together by the common use of the Arabic language - arose only in the late 19th century.

Strange as it now seems, no such idea ever existed before then. In prior centuries, Arabic speakers identified themselves by religion and by region, almost never by language. Language became an important element of identity only under the impact of European political thought. The idea of language defining a people aroused a strong response among Arabic speakers of the Middle East. Christian Arabs picked it up first: by emphasizing language, they found a way to bridge the religious differences that existed between themselves and the vast numbers of Arabic-speaking Muslims around them. The Christians' stress on Arabic as the basis of nationality spread rapidly to the Muslims, who associated it with Islam. Before long, the idea of a single Arab people gained widespread acceptance in the Middle East.

From the 1890s until World War II, Arab referred to Arabic speakers of the Middle East (the second definition discussed above). The third meaning grew later from the second; inexorably, Arab grew to include everyone who speaks Arabic. Egypt became Arab at the close of the Second World War (an event marked by the establishment of the Arab League headquarters in Cairo), followed by the North African countries in the 1950s, Mauritania in the 1960s, and Somalia in the 1970s. This third meaning is now so firmly entrenched that it is hard to imagine how few of these peoples considered themselves Arabs until recently.

Of the three competing meanings, which is the most useful? The first can always be replaced by Arabian; the third meaning is too broad; for most purposes, Arab refers most accurately to the Arabic speakers of the Middle East (in Arabia, the Fertile Crescent, Egypt) just as it did in the early part of this century. Middle Eastern Arabic speakers share enough in common to warrant a single name for them, while the grand totality of Arabic speakers does not.

The geography, history, anthropology, economics and high culture of Middle Eastern Arabic speakers show cohesion. They share an ecology (the arid zone close by deserts), a common civilization going back five thousand years (long antedating the fifteen hundred years or so many of them have spoken Arabic), and a political legacy (four hundred years of Ottoman rule, 1517-1915). Middle Eastern Arabic speakers have always been in close contact with each other; their folk customs and high culture alike vary comparatively little.

Egypt is hard to place within this schema; its population has often equaled that of both Arabia and the Fertile Crescent combined. It stands apart; although Egypt has always been in close contact with the rest of the Middle East, it has also had both the isolation and the size to constitute its own original and distinctive culture.

Whereas the Arabic speakers of the Middle East, with or without Egypt, share many aspects of life in common, the same cannot be said for African Arabic speakers. The North Africans shared little in pre-Islamic times with either each other or with the Middle East; in Islamic times too, they came under different rulers, developed strikingly different folk cultures, economic patterns, and religious emphases.

Arabic speakers of Africa share only three important features with those of the Middle East: religion, high culture and antipathy to Israel.

1. Since most Arabic speakers are Muslims, they share all that Islam brings (on this, see below about Islam). Yet Islam has nothing to do with language: all Muslims, whether or not they speak Arabic, share Islam. Islamic characteristics are not associated with speaking Arabic.

2. Whereas spoken dialects of Arabic differ widely from each other, standard Arabic is everywhere virtually the same in both its spoken and written forms. Having divergent vernaculars and a universal high language has the effect of isolating the culture of the educated from local influences, making it the preserve of all literate Arabic speakers. Just as medieval Europe shared a Latin culture subject to few local influences, so is Arabic high culture the common heritage of cultivated Arabic speakers, regardless of location.

3. On a political level, a unified hostility toward Israel serves as the main vehicle for expressing Arabic speaking solidarity. On this one issue the Arab identity has inspired nearly similar feelings (if not similar policy); for this reason, a break in the ranks vis-à-vis Israel provokes howls of protest among Arabs. Yet, even here, Arabic speakers of Africa (in Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt) distinguish themselves from Middle Easterners by their flexibility.

Two final points follow from this assessment of Arabs: first, there is no historical basis for an "Arab people" and even less for an "Arab race". Arabic speakers count among themselves diverse peoples such as Arabians, Yemenis, Egyptians and Berbers. Sharing a language implies nothing about the ethnic or racial qualities of these peoples.

Second, a noisy campaign to unite all Arabic speakers has captured wide international attention during the past twenty years. Pan-Arab nationalist ideology ignores existing national boundaries in favor of a single nation comprising all Arabic speakers, ideally stretching from Iran to the Atlantic. A universal Arab state has widespread appeal but is utterly futile; Arabic speakers are too heterogeneous, too spread out, too fractured politically for them ever to unite. The total failure of repeated attempts at merger since 1958 (the most recent being between Libya and Syria) implies that future efforts will also collapse. Pan-Arab nationalism has had an unfortunate influence on Arab political life, despite its evident failure. It prevents nations from devoting full attention to domestic affairs in favor of sterile foreign adventurism; it has inspired intransigence and war against Israel; and it embroils relations between the Arab governments. For example, the ideals of pan-Arabism gave foreigners (Syrians, Iraqis, Libyans, Egyptians. Saudi Arabians) a stake in the Lebanese civil war of 1975-77 and justified their actions there, although these transformed a local feud into a national conflagration.

To sum up: in modern[5] high cultural and political life, Arab means "all Arabic speakers"; otherwise the term makes most sense as "Arabic speakers of the Middle East."

Semites. The Semites - primarily Jews and Arabs but also other peoples who speak Semitic languages - are thought to be ethnically and racially related on two grounds: the Biblical account in Genesis x- xi and the common elements in their languages.

The term Semite derives from the proper name Shem, son of Noah and ninth generation ancestor of Abraham. Abraham in turn fathered Isaac and Ishmael, progenitors of the Jews and Arabs respectively. Thus, according to the Bible, Jews and Arabs share common ancestors.

Even if one takes this Biblical account as literal truth, it says little about Jews and Arabs today, four thousand years later. Few present-day Jews are descended only from the ancient Hebrews; and we have already noted that the term Arab, which originally referred to peoples of the Arabian Peninsula, came to mean a much larger group of peoples. Family bonds between Jews and Arabs in the ancient past mean almost nothing today.

August Ludwig von Schlözer invented the term "Semite. |

But severe problems arise when the term is applied to persons. As a shorthand, "speakers of Semitic languages" are called "Semitic peoples" or merely "Semites" - and herein lies the danger. This transfer of meaning implies that people who speak related languages are genealogically or ethnically related too. But languages do not provide a reliable guide to race, for the simple reason that they get changed around. Some languages spread, others are forgotten. Linguistic flux makes it usually impossible to characterize a people's ancestry by its language or language family. Two examples should make this clear.

Until about the 12th century. English was spoken exclusively by a small insular people inhabiting southeastern Britain; over the next centuries, it spread around the world and become mother tongue to persons on every continent. While all English speakers did once share an ethnic bond, no one can claim this today around the world, or even just in the United States. Imperialism was the key to the spread of English; as the British conquered and settled in America, Africa. India, Australia and elsewhere, they imparted their language to new peoples.

The imperial career of Arabic took place about a millennium earlier. Arabians settled in all the regions where Arabic is presently spoken soon after their conquests in the 7th century. With time, Arabic supplanted other languages and became mother tongue to diverse peoples. Other Semitic languages spread in similar, if less spectacular ways. While few non-Jews adopted Hebrew, the racial composition of the Jews changed substantially over the centuries; and Semitic languages in Ethiopia supplanted non-Semitic tongues. Even if the Biblical genealogy linking Arabs, Jews and other ancient peoples to Shem were exactly correct, this tells us virtually nothing about the peoples who speak Semitic languages today.

There are, in short, no Semites, no Semitic race, no Semitic mentality, or a Semitic nose. The noun Semitic should never be used and the adjective Semitic refers properly only to language and some aspects of culture. Anti-Semite also makes no sense, for a person may be anti-Jewish or anti-Arab, but presumably he does not hate the languages those peoples speak.[6]

Islam. "Islam" refers either to a religion or a civilization.[7] In its first, more narrow sense, it is a monotheistic faith, comparable to Judaism or Christianity; in the second usage, it compares with the Chinese, Indian, or European civilizations. These two meanings of "Islam" imply disagreement over the extent of its sway; is it confined to matters spiritual or is it a whole way of life?

This argument reduces to a debate over the shared elements of Muslim life. Advocates of Islam as civilization point to the many common features of Muslim life and conclude that Islam must play a role; those who think not explain those features without reference to Islam or stress the manifold differences in detail and spirit.

Proponents of Islam as a religion only argue that it does not help to understand the economics, warfare, urban life, social organization or other facets of Muslim life; these depend entirely on factors of time and space, on specific historical developments. As proof, they point to the wide diversity among Muslims ranging from the early tribes of Arabia to today's metropolises, from the savannahs of West Africa to the tropics of Indonesia. They note that the Muslims of a given region, say southern India, share more with the non-Muslims living around them than with the Muslims of some remote place, say the Balkans. They are impatient with attempts to seize on Islam and ascribe almost everything to it.

Those who favor a wide usage of Islam accept the importance of time and space but note that the influence of Islam is felt in many domains beyond the strictly spiritual. In the first place, Islam includes a code of law, the Shari'a, which regulates virtually every aspect of human endeavor. Second, Islam has historically brought with it a large number of customs, attitudes and institutions which, though not required by the Shari'a, have become characteristic of Muslim life. These include methods of education, the place of women in society, relations between ruler and ruled, and reactions to the modern West. The more thoroughly Islamized a community, the more it shares with other Muslims in these regards. Despite many variations, key themes do constantly reappear among Muslims from West Africa to Indonesia, from the seventh century until the present.

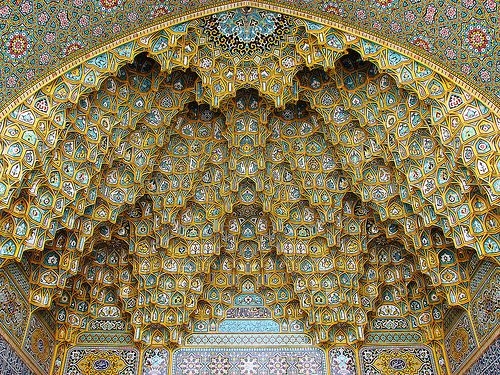

The muqarnas is uniquely Muslim and found in many parts of the Muslim world. |

Daniel Pipes, the author of Slave Soldiers and Islam (New Haven, 1981) and frequent contributor to the national press on current developments in the Middle East and the Islamic world, is currently associated with the Department of History, The University of Chicago.

[1] The buffer zones include: the Mediterranean Sea, the Sea of Marmara, the Black Sea, the Caucasus Mountains, the Caspian Sea, the Kazakh Steppe, the Hindu Kush, the deserts of Afghanistan, Rajasthan, Sistan, and Baluchistan, the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the Nubian Desert, and the Libyan Desert.

[2] Hellenism lasted the shortest period in Iran (until the early third century A.D.) and the longest in Anatolia (a full millennium more).

[3] Two other meanings also exist: Arabic speaking inhabitants of the desert (this is commonly used among Arabic speakers themselves but rarely in English) and Muslims. Although the identity of Arabs and Muslims occurs commonly, it is utterly inaccurate; some Arabic speakers are not Muslims and most Muslims do not speak Arabic.

[4] Including also small numbers in Iran, Turkey, Central Asia, and elsewhere.

[5] In pre-modern times, the widest meaning of "Arab" had no validity at all. Needless to say, Israel did not exist, and the Arabic speakers had no political identity whatsoever. On a cultural level too, the term serves no purpose, for although all Arabic speakers then as now shared a common high culture, so too did many other Muslims. Until recently, educated Muslims learned Arabic to study religious and legal texts; knowledge of the language then opened the way for them to participate in high Arabic culture. Belles lettres and abstract thought expressed in Arabic remained a part of the common Islamic heritage until modern times, when most non-native Arabic speakers abandoned it for European languages.

[6] Of course, anti-Semitic is just a modern way of saying anti-Jewish and few people understand it as anything else; still the inaccuracy of this term does cause mischief. Some anti-Semites point to their affection for Arabic speakers to prove they are not anti-Semitic; and Arabs themselves can even claim that they are incapable of being anti-Semitic since they are Semites themselves.

[7] Some, illogically, also use "Islam" as a geographic expression.

Jan. 4, 2005 update: For another discussion of terminology, see today's "Palestinian Word Games."