ROME – Italy is in the news these days for two main developments. First, Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has – against massive opposition from the media, the judiciary, and the church – shut the country's ports to illegal migrants and thereby reduced the number coming from the Mediterranean Sea by 97 percent between 2017 and 2019. Second, his civilizationist party, the League (Lega in Italian), went from winning 6 percent of the votes in the 2014 European parliamentary elections to 34 percent in those same elections last month, making it by far Italy's most popular party.

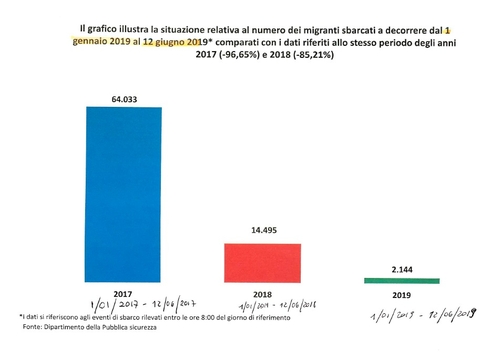

A comparison of sea-borne illegal migrants entering Italy between Jan. 1 and June 12 in 2017-19. Source: Italy's Department of Public Safety. |

Seen from outside Italy, these dramatic developments suggest that growing numbers of Italy's 61 million inhabitants have stopped denying their country's apocalyptic immigration and Islamization problems and are ready to confront the country's existential threats. But is this really the case, have Italians turned a corner in the battle to control their destiny? What do the port closures mean and how significant is the rise of the League?

To research these questions, I spent a week in Rome, meeting with 25 politicians, diplomats, journalists, and intellectuals espousing a wide range of views; Salvini was compared to everyone from Juan Perón to Margaret Thatcher. I came away impressed by the scope of the battle underway, one in which the civilizationists enjoy a momentary and vulnerable advantage that missteps could quickly reverse.

The red drop marks the Italian island of Lampedusa, Europe's territory closest to Libya. |

Worse, the two dominant cultural forces in Italy – the Communist Party and the Roman Catholic Church – are both universalist, with little appreciation for what makes Italy a distinct nation. Naturally, both favor large-scale immigration, as expressed by Pope Francis' ardent statements. On May 27, for example, he called the presence of migrants "an invitation to recover some of those essential dimensions of our Christian existence."

In addition to these lofty reasons, other Italians have more practical ones to want an unceasing flow of migrants. Italy's Left cannot but notice how the migrant vote helps its counterparts in other countries (e.g., France). State-funded migrant services, which employed some 36,000 people, let go of 5,000 employees when the number of illegals dropped, with another 10,000 expected to be laid off. Corruption, including embezzlement and prostitution, is endemic to those services, with the Mafia making "vast profits off the backs of migrants."

On the other side stand those who wish to celebrate not just the nation of Italy and its glorious national culture but also its many distinctive regions, with their long histories, mutually-unintelligible dialects, and renowned cuisines. Venice, for example, enjoyed independence through eleven centuries (697-1797), developed a unique method of glass-making (Murano), and has its own school of music composition. Civilizationist pride in this heritage stands in direct contrast to universalist attitudes.

The person of Matteo Salvini, 46, drives the civilizationist impulse to preserve. A career politician who joined the then-marginal Northern League at age 17, he became a Milan city councilor at 20 and rose through the party ranks, finally taking on and defeating the party's long-time boss in 2013. As the new leader, he quickly turned a regional party into a national one (dropping "Northern" from the name) and made control of immigration his central message.

Interior Minister Matteo Salvini often wears local jerseys to emphasize regional pride even, as here, in Italy's south. |

Salvini so dominates the League and drives Italy's politics that the country's future course depends in large part on his priorities, skills, depth, vision, and stamina. Should he succeed in turning the ports closure into a long-term solution to the problems of immigration and Islamization, his current electoral success presages a watershed for Italy. But if he fails in this attempt, Italians will not soon again have an opportunity to control their borders and assert their identity and sovereignty.

In larger terms, Italy has the potential to join Hungary in leading Europe out of its current decline; but this happy prospect requires enormous skill and more than a pinch of luck.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2019 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

June 17, 2019 addenda: This article is considerably more upbeat than the one I published a year and a half earlier, "Italy's Apocalypse."

(1) Paolo Quercia of Perugia University points out to me that in past years, "Italy spent more than half of its defense budget on rescuing and then maintaining the basic costs of illegal migrants coming from Africa." It then spent much more on training, education, and cultural integration.

(2) In addition to winning 34 percent of the European Union parliamentary vote in late May, Lega also caused the Left to lose some long-time strongholds in Italy's May-June municipal elections (Forlì, 50 years; Ferrara, 69 years). The town of Riace, whose leftist mayor became globally famous for eagerly welcoming migrants from Africa and South Asia and whose population at one point was nearly a half immigrant, now voted in a Lega-supported mayor.

Riace, a village in Calabria. |

(3) Not surprisingly, given their diametrically opposed views on illegal migrants, the pope and Salvini bitterly criticize each other. Salvini directly addressed "His Holiness, Pope Francis," telling him that barring illegal migrants reduces the number who drown: "the policy of this government is eliminating the dead in the Mediterranean with pride and Christian charity." Pope Francis forthrightly replied: "We hear the plea of persons in flight, crowded on boats in search of hope, not knowing which ports will welcome them, in a Europe that does open its ports to ships that will load sophisticated and costly weapons capable of producing forms of destruction that do not spare even children."

(5) A Rome-based criminologist told me that "there has been no terrorism in Italy in 25 years." When I reeled off a number of incidents – the 2003 synagogue attack in Modena, the 2004 McDonald's incident in Brescia, the 2016 planned attacks on the Vatican and the Israeli embassy, the 2018 arrests of jihadis in Rome, Latina, Turin, and Foggia – he went completely silent. In other words, Italy faces the usual problem of the 6Ps (police, politicians, press, priests, professors and prosecutors) living in denial.

Sep. 5, 2019 update: I emphasized in the article above that "civilizationists enjoy a momentary and vulnerable advantage that missteps could quickly reverse" and that Italy's future course "depends in large part on [Salvini's] priorities, skills, depth, vision, and stamina." Well, Salvini's ambitions outpaced reality and today the Lega finds itself excluded from government. This could prove to be positive in the long term but right now it rates as a terrible mistake.

Sep. 26, 2022 update: Salvini has been pushed aside by Giorgia Meloni, head of the civilizationist party, Brothers of Italy, winner of yesterday's election, and likely next prime minister of Italy.