Approaches

"Military slavery" refers to the systematic use of slaves as soldiers. It does not include all slaves who fight in war but only those acquired and trained in an organized setting and then professionally employed as soldiers. In contrast to these military slaves, I call those who are normally engaged in other activities and only fight as a result of specific circumstances "ordinary slaves."

"Military slavery" refers to the systematic use of slaves as soldiers. It does not include all slaves who fight in war but only those acquired and trained in an organized setting and then professionally employed as soldiers. In contrast to these military slaves, I call those who are normally engaged in other activities and only fight as a result of specific circumstances "ordinary slaves."

Ordinary slaves fought in wars all over the world, helping their masters in various support, auxiliary, and emergency capacities. They brought occasional assistance but never constituted a decisive military weapon; nor did they make up the mainstay of any army. In all, ordinary slaves fighting in war are only a minor phenomenon.1

By contrast, military slaves have had real importance. As well-trained and professional soldiers they served their masters over years, formed the mainstay of numerous armies, and often had a decisive military role. Further, by virtue of their military importance, they acquired a power base which allowed them on occasion to wield an independent political role; sometimes, this even ended in their taking over the government and appointing one of their own as ruler.2

The attempt to explain the rationale behind military slavery must take into account its distribution. Military slavery did not occur here and there around the world but, it would seem, only in Muslim countries. Muslim rulers alone systematically recruited their soldiers through enslavement. Not only this, but Muslims made very heavy use of such slave soldiers, for they may be found in nearly every Muslim dynasty between the ninth and the nineteenth centuries, between Spain and Bengal, Central Asia and Central Africa. A close look at almost any Muslim dynasty before 1850 turns up countless slaves in the army and many in positions of power and prestige. Although not everywhere (not east of Bengal) nor at all times, (not in the seventh, eighth, or twentieth centuries), military slavery existed so frequently in Muslim armies that it can be considered their single most distinctive feature.

The profusion of military slavery in the Muslim countries and its absence elsewhere suggests that its rationale must be connected to Islamic. culture. How else can one explain the existence of a single institution (with admitted variations) in so many Muslim dynasties, regardless of political, geographic, economic, or social conditions? Islam alone ties these many dynasties together; hence the surmise that the rationale of military slavery can only be found in Islamic culture. Something in Islamic culture calls military slavery into being: what is it?

Possible Connections to Islam

The connection to Islamic culture might be tied tither to the religion or the civilization of Islam. For while Islam is at base a religion, it is also more, a legal system and a way of life. Like Judaism and unlike Christianity, Islam includes a sacred law which regulates in detail the activities of believers. It touches everything, starting before sunrise when the Muslim rises for the first prayer and ending when he goes to sleep m an approved position.

Of course, few Muslim communities adhere strictly to all the laws, yet the laws remain important even when unfilled. They represent an ideal and exert a similar pull on divergent communities. The web of relations, attitudes, and patterns which follow make up the distinct and unique civilization of Islam. It does not follow directly from either the religion or the sacred law but exists because of them.

Returning to the question at hand, is military slavery connected to the religion or to the civilization of Islam? If to the religion, that would imply that military slavery is part of the Islamic religio-legal system, a characteristic, non-functional feature of the religion, comparable to the presence of Sufi (mystical) brotherhoods or the wearing of turbans. This, however, cannot have been the main connection, for military slavery has no religious or legal sanction, it meets no doctrinal need, and it is not even unambiguously legal. It does not accompany the Islamic religion as part of an Islamic package.

Therefore, military slavery must be somehow related to the general civilization of Islam. What aspect of Islamic civilization could call this institution into being? Nearly all attempts to answer this question arrive. at the same conclusion: the need for agents. Social thinkers and historians of Islam alike stress this explanation.

Montesquieu appears to have been the first writer to reflect on the arming of slaves,4 but H. J. Nieboer may have been the first to explain the phenomenon. In his comparative work on primitive slavery published in 1900, he states that "the owners of numerous slaves, who form the aristocracy, will often be inclined to rely on their slaves for the maintenance of their power over the common freeman."5 Nieboer's view reflects the first influence of Marxist analysis at the very end of the nineteenth-century. He sees soldiers of slave origins as a consequence of class conflict; slaves serve as a political tool in supporting the aristocracy against the masses.

Max Weber considers slave armies in the context of patrimonial authority and explains their development through political advantage. Just as a patrimonial ruler prefers to recruit administrators from his household personnel, because they are most loyal, so he will find the most devoted troops in his own household.6 Slave soldiers serve primarily as agents of the ruler's will.

S. Andreski explains military slavery in reference to alienated officebearers; among other countries, the Islamicate ones experienced

a violent struggle [which] went on continuously between the rulers and the magnates. In the deadly struggle against the magnates, the rulers often employed slaves and mercenaries recruited from the lowest strata. These troops revolted frequently and, on some occasions, deposed the rulers, decimated and despoiled the nobility, and put themselves in their place.7

Andreski too emphasizes military slaves serving the ruler as agents in his internal political relations.

Like the sociologists, historians of Muslim countries also find a political rationale. The Fishers emphasize military slavery as a means to increase centralization even to achieve despotism,8 while Papoulia sees it as a force to resist decentralization.9 Vryonis stresses the "multi-sectarian, polyglot, and multi-racial" nature of major Muslim dynasties and interprets military slavery as a method of coping with this situation.10 Sadeque notes that the geographic and sectarian fracturing of Islamicate polities weakens the governments and accounts for the need for slave soldiers.11 Meyers similarly points to the fact that "Muslim conquerors were normally small and internally segmented groups."12 A. Lewis attributes it to the "anarchic individualism of social and particularly political patterns" in Muslim life.13 Hrbek echoes Nieboer's explanation by writing that the appearance of military slavery results primarily "from the fact that the rulers could not trust their own subjects and could not build an army from among their ranks."14

All these explanations of military slavery, most clearly articulated by Andreski, imply that it serves a ruler by bringing lowly elements into the government. Through enslavement, the Muslim leader attaches to himself men from the humblest stratum of society who become his trusted agents in his struggles with domestic rivals. Faced with incessant internal opposition, the ruler enrolls slaves; their complete devotion helps him stave off all challenges. Military slavery is a political manouvre to acquire agents against internal rivals.

In my view, the possibility of using military slaves as agents added to their value but did not constitute their raison d'être; for agents served political purposes and military slaves were foremost soldiers. While they often had non-military functions too, these slaves were acquired, trained, and employed on the strength of their ability to fight. Other functions only followed from their successes on the battlefield. So, though military slaves served their master well as agents, their rationale lies elsewhere, in the benefits they brought to him as soldiers. What were those?

To answer this question, we must look at the characteristic needs of Muslim armies, which alone depended on military slaves. Did they have needs not found in other armies? How might these have called military slavery into being?

I shall argue that Muslim armies did have unique needs and that military slavery went some way to solve them. In a nutshell; the subjects of Muslim rulers were rarely willing to fight for him, so the ruler had to find soldiers outside his domains. Military slavery served the ruler both. as a mechanism to acquire outsider soldiers and a method to bind them to himself.

Outsider Soldiers Dominated Muslim Armies

From the birth of Islam until the early nineteenth century, from Bengal to Spain, almost all soldiers supporting an Muslim central government came from outside the dynasty.15 These alien soldiers founded nearly all Muslim dynasties and staffed their armies. The heavy reliance by Muslims on soldiers from distant areas constituted one of the most basic and important patterns in Islamic history. No other armies, not even those which existed in the same regions before they came under Muslim control, depended so heavily on this type of soldier. ·

This is not the place to document such an important feature of Islamic life; one example will suffice to make the point clear, the case of Egypt. In pre-Islamic times Egyptian soldiers from the Nile Valley formed the mainstay of imperial Egyptian armies, especially in the Pharaonic period, but also in Greco-Roman service. Their role ended abruptly with the Arabian conquest of Egypt in 642. From then on until the nineteenth century, soldiers supporting the government of Egypt came from outside Egypt. Every new dynasty came to power with soldiers from outside Egypt: the Umayyads, Abbasids, Tulunids, Ikhshidids, Fatimids, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Ottomans, and Muhammad 'Ali's line. After the founding of a dynasty, it continued to rely on the same type of soldier too, with very little dependence on Egyptians. The same pattern existed in many other Islamic regions as well, including Morocco, Tunisia, the Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Anatolia, Western and Eastern Iran, Central Asia, and northern India.16

The extraordinary role of outsider soldiers in Muslim countries explains many of the most characteristic features of Muslim military, political, and social life; military slavery is just one of those features. Reliance on outside soldiers entailed specific needs; military slavery developed to meet those needs. This section looks at the reasons why outside soldiers dominated Muslim armies and the needs this situation created.

Abdication of Power by Muslim Populaces

Muslim rulers employed soldiers from outside their domains because the indigenous population relinquished its military and political power. This surprising development occurred as a result of two distinctive features in Islamic political life: the de-emphases on (1) territorial identification and on (2) military relations between Muslims.17

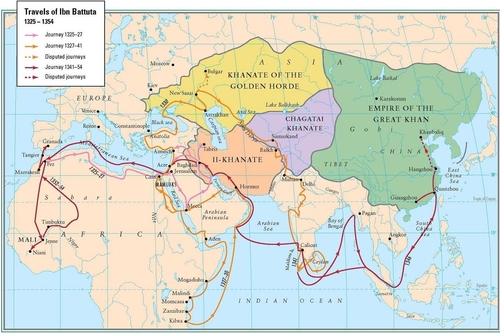

(1) Islamic civilization discourages strong identification with a geographic region. Muslims have few local saints, well-defined regions, or dynasties tied by origins and sympathies to a particular place. The Fatimids – who originated in the Yemen, then floated to Tunisia, Egypt, and almost to Iraq – had to have been Muslims. In modern times, only a Muslim state, Pakistan, could comprise two wings separated by a thousand miles. When the great Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta (d. 1356) landed in the Maldive Islands, he knew nothing of its language or culture, yet he quickly found himself employed as a cadi (judge).18 The Islamic element had such importance that he could serve in an alien environment.

The travels of Ibn Batuta. |

This fluid geographic attitude may be attributed to the Islamic stress on family and umma (community of Muslims) over place. Most Islamic affiliations were directed either to the very near or to the universal; middle level associations (to the region or city) received distinctly less encouragement. In political matters, this led to an emphasis on the ruler of the umma, the Caliph, to the detriment of local, territorial rulers. Although territorial affiliation was never entirely absent, it usually had less importance than either kin or Islamic ties.

Notions intermediate between tribal and Islamic were hazy and of doubtful social significance. Such loyalties as have from time to time crystallized in in the middle area between the tribal ceiling on the one hand, and the universalist claims of Islam on the other, were ephemeral and were not firmly articulated in either ethnic or territorial terms.19

No matter how fragmented the real situation was, Muslims always held up the unified policy as an ideal. In consequence, local rulers appeared in some vague way as usurpers, for they divided the umma and led Muslims to war against each other. Muslims ached for unity and denied territorial rulers full respect or loyalty; this feeling was symbolized by the practice of investing sovereignty in a powerless caliph who lived thousands of miles away. Territorial rulers responded to the bias against them by adopting universalist pretentions:

For a Muslim sovereign, the only acceptable definition of the extent of his sovereignty was Islam itself. ... A territorial or an ethnic designation was derogatory and was applied to a rival to show the limited and local nature of his rule.20

The titles which Muslim rulers adopted reflected this fact, for they did not "normally include any designation of the territory or people over which the sovereign claims authority."21

The denigration of local, territorial rulers had clear political consequences; it prevented them from relying on their subjects for loyal service. Pre-modern Muslim governments tended not to develop strong local roots, but remained dynasties of powerful, isolated individuals who relied on the support of outsiders. Their subjects felt little attachment to the rulers; they directed their loyalties either to the near (family, tribe, village) or to the entire community of Muslims. The reluctance of the local, majority populace forced the rulers to find their support elsewhere, from outsiders.

(2) Islam discourages participation in struggles between Muslims. By accentuating the dichotomy between Muslim and non-Muslim, it reduces the role of the local populace when no non-Muslims are involved. Islam cares little who rules, so long as he is Muslim; therefore, Muslim peoples get involved only when non-Muslims are threatened. They took a sudden interest in jihad, in sharp contrast to their usual unconcern with politics and war. When the infidels were at bay and a government which supported the Qur'an and Sunna was in power, the people tended their own gardens. This amounted to a voluntary abdication of their own military and political role and it led to the domination by outsiders. Muslims generally involved themselves less in politics than other peoples. Paradoxically, by embracing politics, Islam withdrew it from the lives of most Muslims.

Combining (1) and (2), we find that the Muslim peoples at most times showed almost no interest in participating in their own army or government. They viewed their own rulers as transient, as not quite legitimate and stayed out of the way. Their political passivity and disaffection made them poor support; their passive acceptance of the political order created an enormous gulf between rulers and ruled which, in the normal course of events, was rarely overcome. Territorial rulers constituted nearly all Muslim rulers after 205/820, yet they could not rely on their subjects for support; hence, they looked outside the majority populace for help.

When Muslim rulers consistently looked outside their own domains for soldiers, they developed a unique need, one not shBred by non-Muslim rulers; it was this need for outsider soldiers which brought military slavery into being. Above all, in searching for soldiers from outside, the Muslim ruler needed a steady supply of recruits and a way to bind them to himself. Military slavery filled these two needs.

The Benefits of Military Slavery

The easier acquisition and greater loyalty of military slaves stand out most clearly when compared to the alternate methods of recruiting outsider soldiers: as free men, either mercenaries or allies.

Acquisition of Outsider Soldiers

A government could procure slaves more easily than either mercenaries or allies. It might purchase, capture, abduct, or steal a slave, but not so a free man. A slave could be compelled to join the army, but not the others; mercenaries had to be enticed to serve and allies had to find it expedient. The slave was subject to more active and flexible means of persuasion. By recruiting him through enslavement, the ruler extricated himself from having to wait until co-operative soldiers appeared,22 the common predicament of governments which did not enslave soldiers (e.g. Byzantium and China). In contrast to the limited circumstances in which mercenaries or allies agreed to fight, slaves came as circumstances allowed; some arrived as tribute, others as merchandise, booty, contraband, or stolen property.

Military slaves were procured usually as children and this too facilitated their acquisition. While mercenaries and allies could only be found among friendly peoples, children could be abducted or captured in war from enemies and, through training, made into faithful soldiers. The pool of potential slaves could be many times larger than that of free recruits.

Enslavement gave access to a wide variety of nationalities and they provided the army with a beneficial diversity of troop , as they often brought with them the special skills of their own peoples.23 This multiplicity of ethnic backgrounds and skills contributed directly to the flexibility and tactical power of Muslim armies. Though mercenaries and allies too could come from many peoples, the rulers had much less control over their sources.

Further, by enslaving his recruits, the Muslim ruler could choose his soldiers man for man. Mercenaries and allies arrived in corps or tribes and fought as a group; slaves, however, came singly. The government could exercise a careful selection over its slaves which was not possible with free marginal area soldiers. This selectivity made possible a higher standard of quality for each soldier in slave armies.

Along with these benefits, the procurement of military slaves also involved some special problems. As a dynasty declined in strength, it could no longer acquire its slaves inexpensively (through raiding, warfare, and so forth) but had to purchase them. Yet, as the dynasty weakened, its resources diminished, so this expense grew ever more burdensome. The Mamluks of Egypt could not reduce their dependence on new recruits or acquire them inexpensively, so the price of buying slaves contributed significantly to the economic decline of the country.24

The distance over which slaves usually travelled from their homeland to their country of service and the fragility of the supply lines could also cause problems.25 Since the slaves usually came from remote regions, enemy forces could easily disrupt access to them. Abbasid dependence on the Tahirids to send them slave children reduced Abbasid control in northern Iran and added to the Tahirids' strength.

The expense and the distance over which military slaves travelled presented two drawbacks peculiar to slave soldiers, but only in times of decline; these problems were not envisaged when a ruler founded a military slave corps in the second generation or so of the dynasty.

Control of Outsider Soldiers

Newly recruited soldiers as total aliens and outsiders, without affiliations to either the ruling powers or to the polity population.

How could their master bind them to himself and his dynasty? As mercenaries or allies, they retained their own loyalties, but as slaves, they could be subjected to re-orientation. Prior to enrolment into the army, they were prepared for service; the government secured their loyalty and fitted their military skills to the-needs of the army.

(1) Loyalty. Mercenaries and allies imposed their fickle loyalties on the ruler. They could always desert, and they permanently threatened to mutiny; "an ally was always a potential threat to independence"26 and a mercenary was even more so. Since these troops often constituted the most powerful force in the kingdom, little could prevent them from becoming an unmanageable and destructive element, indifferent to an allegiance which blocked the way to booty. If dissatisfied with their plunder from warfare, they readily attacked their own employer or ally.

Military slavery provided a handle by which to control alien soldiers. Unlike mercenaries and allies, they could be compelled to undergo changes in identity; these changes were effected through the complementary processes of deracination, isolation, and indoctrination. Deracination exposed slaves to loneliness and new relationships; isolation furthered their susceptibility; and indoctrination transformed their personalities.

Unlike mercenaries and allies, who usually came in tribal units and stayed in them, keeping their old loyalties, slaves came as individuals and had to build up new attachments. Deprived of their own people, these soldiers had to adopt the new affiliations offered them. The military slave corps developed into a substitute tribe and replaced the true kin group in many instances. The adoption of a master's nisba (kin name) reflected the need for a new, albeit fictitious, filiation.27

The master also isolated his slaves. He took them from their homeland to a strange country and cut them off from the rest of the society. They had no choice but to accept the affiliations provided them and to become loyal to him. They developed close relations with their comrades, all of whom shared a similar predicament. Geographic isolation also reduced the possibility that a marginal area soldier would have to fight his own people by taking him far away from them. Combat against co-nationals strained even the loyalty of a military slave, though many examples of their loyalty in such situations can be found.28

Finally, military slavery allowed indoctrination. Whereas mercenaries and allies arrived fully developed and resisted changes to their personalities and loyalties, military slaves came as children, unformed and susceptible to re-orientation. Years of careful schooling imbued them with life-long attachments to the Islamic religion, their master, his dynasty, and their comrades-in-arms. The master exerted continuous pressure on the slave recruits to abandon their prior allegiances in favour of himself. Enslavement made possible the extended period of gestation which changed their identities. Ibn Khaldun explains:

When a people with group feeling train another people of another descent or enslave slaves and mawlas, they enter into close contact them ... These mawlas and trained persons share in their patrons') group feeling and take it on as if it were their own.29

(2) Military training. The training process was the linchpin of the whole institution of military slavery. It established a slave's character by instilling military skills, discipline, and an understanding of command structures. The years of training marked off the military slave and determined his future career. He entered training an isolated boy and emerged a highly skilled, disciplined, connected soldier. The mercenary or ally, not compelled to undergo training, usually lacked these important qualities.

Military slaves received training in the martial arts first. Where mercenaries and allies showed impatience, slaves learned new methods of fighting.30 Their servile status and their youth combined to force them to accept these changes. Outsider soldiers often arrived in the polity brimming with independent spirit and unfamiliar with chains of command, yet governments could not tolerate such chaotic qualities, so they forced the slaves to learn discipline.

Through military training, the natural courage and hardiness of these soldiers was combined with the organization, techniques, and discipline of polity armies. The slaves emerged superbly accomplished in the martial arts and fully integrated into an organized army. The main drawback of the training programme lay in the time it required; while mercenaries and allies came fully prepared for battle, military slaves had to be acquired and trained far in advance of their application. They could be properly used only in the context of long-range planning.31

(3) No competing interests. Mercenaries and allies invariably had concerns outside of their military service. They had family, kinsmen, herds, farms, and so forth, to which they devoted attention and from which they were loath to be long separated. These interests required time and conflicted with their service to the ruler. Slaves, to the contrary, could be made to live in isolation from the rest of society. Not only could they be prevented from having outside income, but they could also be kept celibate; surely the ruler could not compel any but his own slave not to marry. In return for receiving all their income in salary from the ruler, the slaves served him all year as a standing army.

(4) Acculturation. Military slaves came far more completely under the cultural influence of the polity than their free rivals. In training, they learned the customs, religion, culture, and language of the dynasty; this proved to be of great importance, for unless they were made to feel part of the dynasty, they could always turn against it. Military slaves never did this; they had become part of the dynasty itself. They were part of the· ruling elite, not its lackeys. When they revolted, they did not attack the polity as such but the individuals in charge; if successful, they took the government over from within. This acculturation did not prevent them, however, from preying on the populace of the polity; they engaged in this pursuit as did all members of the ruling elite. Acculturation made them part of the government; so they could not attack the policy itself, though its populace remained their victims.

(5) Agents. Besides bringing military power to the dynasty as a whole, military slaves also provided the ruler with political henchmen. While serving the army against external enemies, they supported the ruler against internal rivals. Although complementary, these two functions were not identical. As agents, they were totally beholden to the ruler, devoted to him and lacking any trace of envy; no better agents could be found. Mercenaries and allies did not reliably provide this personal service.

Conclusion

Muslims alone relied so heavily on alien marginal area soldiers that they developed an institution to acquire and control those troops; the unique composition of Islamic armies thus accounts for military slavery and explains why it existed only in Muslim countries. Muslim leaders could choose to recruit alien soldiers in other ways, but other methods entailed more difficulties. For example, the Mughals had very few military slaves; instead, they employed Hindus from the marginal areas of India, and they attracted soldiers from Iran and Central Asia by offering them especially high salaries.32 However, the Mughals often had problems acquiring these troops and retraining their loyalties. Given the Muslims' need for outsider soldiers, military slavery brought several advantages over other methods of organization; the slaves' numbers, quality, and youth assured the best material; their isolation, training, and indoctrination assured fine and loyal soldiers.

Noting the advantages of military slaves we should not find their military role in the millennium 820-1850 so puzzling. The institution of military slavery was no accident, legalism, or fluke, but a successful adaptation to the specific Muslim need to acquire and control alien soldiers from marginal areas. However odd to our eyes, the enslavement of recruits brought Muslim rulers real military benefits.

In the end, the truly unusual feature of military slavery has little to do with the use of slaves as soldiers; it lies in the cultural rationale behind this institution. The existence of military slavery has almost nothing to do with material circumstances (geographic, economic, social, political, technical, etc.) but follows from the needs inherent in Islamic civilization. In contrast to other forms of military recruitment – say tribal levies, mercenary, militia conscription, or universal service – this one occurs in only one civilization; and there it exists almost universally. To the best of my knowledge, no other method of military organization has comparable connections to a single civilization.

*University of Chicago.

NOTES

1. My Ph.D. thesis, "From Mawla to Mamluk: the Origins of Islamic Military Slavery" (Harvard University, 1978), documents this on pp. 41-55, 205-10. See also a forthcoming article, "Ordinary Slaves in War."

2. I have located about fifty rulers of military slave origins.

3. "From Mawla to Mamluk", p. 83.

4. C. S. Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, trans. T. Nugent (New York, 1949), Vol. I, pp. 243-44, 249.

5. H. J. Nieboer, Slavery as an Individual System (The Hague, 1900), p. 403.

6. M. Weber, The Theory of Social and Political Organization, trans. A. M. Henderson & T. Parsons (New York, 1947), p. 342-3. For an elucidation of Weber's idea, see R. Bendix, Max Weber: an Intellectual Portrait (Garden City, N.Y., 1960), pp. 341-42.

7. S. Andreski, Military Organization and Society (2nd ed. rev.: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1968), pp. 197-98.

8. A. G. B. & H. J. Fisher, Slavery and Muslim Society in Africa (Garden City, New York, 1971), p. 163.

9. S. Vryonis, Review of Ursprung and Wesen der 'Knobenlese' im osmanischen Reich (Munich, 1963), in Balkan Studies, 5 (1964): 146.

10. S. Vryonis, "Seljuk Gulams and Ottoman Devshirmes," Der Islam 41 (1965): 225.

11. S. F. Sadeque, Baybars I of Egypt ([Dacca], 1956), pp. xiv-xvi.

12. A. R. Meyers, "The 'Abid'l-Buhari: Slave soldiers and statecraft in Morocco, 1672-1790" (Ph.D. Cornell, 1974), p. 26.

13. A. Lewis, Naval Power and Trade in the Mediterranean, A.D. 500-1100 (Princeton, 1951), p. 254.

14. I. Hrbek, "Die Slawen im Dienste der Fatimiden," Archiv Orientální, 21 (1953): 543; S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society (3. vols., incomplete; Berkeley), vol 1, p. 132 echoes this view.

15. For the purposes of this article, "outsider" and "alien" are synonymous.

16. Exceptions to this pattern include principally the local dynasties in India as well as other scattered dynasties such as the Saffarids, Samanids, Sardabarids, and several Syrian city polities.

17. The following arguments owe much to discussions with Profs. Shmuel Eisenstadt and Richard Bulliet.

18. Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354, translated and selected by H. A. R. Gibb (London, 1929), pp. 244ff.

19. E. Gellner, Saints of the Atlas (London, 1969), pp. 15-16.

20. B. Lewis, "Politics and war," The Legacy of Islam, eds. J. Schacht and C. E. Bosworth (2nd ed. rev.: Oxford, 1974), p. 174.

21. Ibid., p. l73.

22. Hrbek, p. 545.

23. C. E. Bosworth, The Ghaznavids (Edinburgh, 1963), p. 108.

24. D. Ayalon, "Aspects of the mamluk phenomenon"; Der Islam, 53 (1976): 208; E. Ashtor, "Recent research on Levantine trade," Journal of European Economic History 1 (1973): 201; E. Ashtor, Les metaux precieux (Paris, 1971), pp. 99-108; R. Lopez, H. Miskimin, & A. Udovitch, "England to Egypt, 1350-1500: long-term trends and long-distance trade," Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East, ed. M. A. Cook (London, 1970), p. 127. My thanks to Dr. Boaz Shosron for the Ashtor references.

25. Ayalon, pp. 207-08; Hrbek, pp. 552-53.

26. J. F. P. Hopkins, Medieval Muslim Government in Barbary until the Sixth Century of the Hijra (London, 1958).

27. D. Ayalon, "Names, titles and 'nisbas' of the Mamluks," Israel Oriental Studies, 5 (1975), pp. 213-19.

28. CHI 4.162; P. Wittek, "Türkentum und Islam, I," Archiv fur Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, 59 (1928): 517; andsee the many examples in Chapter 6b.

29. Ibn Khaldun, Al-Muqaddima, ed. E. Quatremère (Paris, 1858), vol. 1, p. 245.

30. For some details on this, H. Rabie, "The training of the Mamluk fãris," in V. J. Parry and M. E. Yapp, War, Technology and Society in the Middle East (London, 1975), pp. 153-63.

31. Ayalon, "Aspects," 208.

32. I. H. Qureshi, The Administration of the Mughal Empire (5th ed. rev.: Karachi; 1966), pp. 124, 132.