Daniel Pipes: I am critical of the report produced by the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies regarding Israel's options vis-à-vis the Palestinian problem, but first let me offer some praise for the effort.

The report is intelligent in its formulations. It is thorough and, in many ways, convincing. It is particularly valuable for clarifying the options available to Israel on this crucial matter. It affords a more solid grounding for a discussion of Israel's future policies. I agree with much of its analysis, especially the point that the six options are all. in one way or another, unsatisfactory.

Where I disagree strongly with the report is with its basic orientation, that is, the underlying assumption that a Palestinian settlement is central to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Israelis have forgotten a piece of essential wisdom they once knew, and the amnesia has spread among Americans. It used to be that the debate between Israel and the Arabs would go as follows: Israelis would say, "This is a conflict between Israel and the Arabs." The Arabs would counter, "No, this is a conflict between Israelis and Palestinians." Then, somehow, in the course of the 1980s Israelis lost sight of what they once understood and they too. by and large. came to accept the notion that the conflict in question is one between Israelis and Palestinians, that is to say, a communal conflict between two small peoples on a small piece of territory.

That premise is untrue. The conflict remains one between states. Further, the Palestinians are who they are and enjoy the strength they do because they are backed by a vast hinterland, stretching from Iran to Morocco, but more especially from Lebanon to Egypt. Therefore, to isolate the Palestinians from this larger context is to miss a key point. To solve only the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is to put out a fire in one house when the whole city is burning - all very constructive, but in the end futile.

To be sure, the Jaffee Center report, as Joseph Alpher has indicated, takes cognizance of the larger context of the Israeli-Palestinian confrontation, particularly the Syrian factor, but it does so only glancingly. So, to my mind, the Jaffee Center's exercise, however clever, is ultimately fruitless, and perhaps even counterproductive.

The heart of the confrontation remains the one between the Arab states and Israel. Of the Arab states, by far the most critical are those that actually touch upon Israel - Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Egypt has been hors de combat, so to speak, for 10 years. Today the Egyptians are interested in other matters, most especially, domestic affairs. The Jordanian government under King Hussein, for years has wished to come to an accommodation with Israel and has, in fact, attained one, albeit covertly. Were circumstances to change, the accommodation could become formal and more explicit. In Lebanon, of course, there is no government; some groups are friendly to Israel and others exceedingly hostile. There is nothing much the Israelis can do there, as they learned to their detriment in 1982-85.

Which leaves Syria. Syria is the one major Arab state bordering Israel that has a major military force, whose government is utterly unreconciled even to the existence of Israel. much less to living in peace with it. The Syrian challenge to Israel remains, and indeed has become even greater as one Arab state after another, particularly Egypt, has fallen away from the fray. The Syrian government has taken upon itself the burden of singlehandedly confronting Israel - which is what the Syrians mean by strategic parity. The area between Damascus and the Golan Heights is the most heavily fortified in the entire world. In the long term, Syrian missiles are far more dangerous to Israel's welfare than stones thrown by children in the West Bank.

Let me draw out this comparison by making an analogy. The United States, for years now, has been trying to reach arms-control agreements with Moscow. How much easier it would be to try to get such agreements with a smaller, more amenable Communist state, say, Yugoslavia. The Yugoslavs are small in number; they are rather friendly; they are amenable to pressure. The trouble is that they don't have the weapons, that they cannot make decisions of war and peace. Yasir Arafat is in a similar position. He cannot deliver on his promises, not even Palestinians, much less the Arab states whose creature he is (and not vice versa).

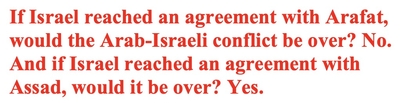

So, if Israel were to reach an agreement with Arafat, and all the conditions on both sides were to be met, would the Arab-Israeli conflict be over? Not at all. The Syrian missiles would still be in place and, very quickly, the mini-state that Arafat and his followers had established would be under severe challenge from the Palestinians based in Damascus. For, indeed, there are two PLOs, as has been the case for most of the past decade: the Arafat PLO and the Assad PLO. The latter includes Habash and Jibril and Abu Musa and Abu Nidal and others of the same ilk. They tend to be dismissed, but they are senior figures in the Palestinian movement; they have thousands of followers; they have money and arms - and they are challenging Arafat. They will challenge him far more directly and decisively if he ever reaches a settlement with Israel.

So, if Israel were to reach an agreement with Arafat, and all the conditions on both sides were to be met, would the Arab-Israeli conflict be over? Not at all. The Syrian missiles would still be in place and, very quickly, the mini-state that Arafat and his followers had established would be under severe challenge from the Palestinians based in Damascus. For, indeed, there are two PLOs, as has been the case for most of the past decade: the Arafat PLO and the Assad PLO. The latter includes Habash and Jibril and Abu Musa and Abu Nidal and others of the same ilk. They tend to be dismissed, but they are senior figures in the Palestinian movement; they have thousands of followers; they have money and arms - and they are challenging Arafat. They will challenge him far more directly and decisively if he ever reaches a settlement with Israel.

Conversely, should the Israelis reach an agreement with Hafez Assad - this is not something in the cards, but let us assume it for the moment - would the conflict be over? I say yes. If the Syrians and the Israelis resolved their differences, then the Jordanians would quickly climb aboard and so too, willy-nilly, would the Palestinians, because they would have lost all significant Arab sponsorship. It would then no longer be in the Palestinians' interest to maintain the hard line they have been bruiting all these years. Their leadership would cease to circumnavigate the globe as a kind of traveling royalty, and their followers would lose the benefits they now enjoy. The conflict would no longer be an international issue and it would therefore also be in the Palestinian interest to come to terms with Israel.

Thus the conflict as it exists today is ultimately one of Syrian-Israeli confrontation, rather than a clash between Palestinians and Israelis. I am not dismissing the significance of the Palestinians, but a report that looks only at the Palestinians, good and welcome as it is, is one that is fundamentally marked by its incompleteness.

A less fundamental criticism of the Jaffee Center report, though still a criticism, is its misunderstanding of Soviet goals. The report has a tendency to ascribe to the Soviet Union a positive and helpful role in the Middle East. In its words: "The USSR is not happy with the perpetuation of the status quo. It seeks to promote a negotiated settlement." But nothing in the record of Soviet diplomacy leads to this conclusion. I grant that in the era of Gorbachev things are changing. Certainly, in some cases the words have changed, but so far there is no change on the ground. To take the Syrian instance, while Mikhail Gorbachev has articulated a new position, very high-grade arms continue to flow into Syria. What can one make of this? Perhaps there is a change in Soviet policy and attitudes, perhaps not; it is too early to say. I advise skepticism with regard to the Soviet Union.

A further criticism is the deficiency of the proposal - contained in the Jaffee Center's independent auxiliary booklet - that is premised on foreign aid for the region to buttress a Palestinian-Israeli accord, aid from the United States, Japan, West Germany, the Arab states. A realistic solution cannot depend on billions of dollars of somebody else's money. There has to be a more rigorous calculation as to how the parties directly involved can succeed on their own. Otherwise, the parties make themselves hostage to too many foreign players.

There is also a premise advanced in the auxiliary booklet that suggests that the two states - Israel and the Palestinian entity-to-be - "should undertake to honor their contractual agreements to one another, even in the event of regime or constitutional changes in one or both of them." This strikes me as preposterous. It is like asking Khomeini to maintain the contracts created by the Shah, or Lenin to keep czarist obligations. You can ask, but don't put too much credence in an agreement.

A final, but critical point: this concerns media simplification of the study under discussion. I call your attention to a cover story on the Jaffee Center study, including the auxiliary booklet, in the French newsweekly magazine L'Express. The headline trumpets: "At what price peace? The document that is dividing Israel." The very first line of the article - written, incidentally, by Shmuel Segev, an Israeli reporter of some reputation - quotes what seems to be the report as follows: "For Israel, a single option remains possible in a search for peace: negotiate with the PLO and acknowledge the eventual creation of a Palestinian state." Such an assertion is nowhere stated in the report. One can see, however, how the notion might have been deduced, for it is very easy to take the carefully modulated language of the Jaffee Center report and tum it into something different by simply removing all of the conditions and qualifications.

Joseph Alpher: Let me respond briefly to Daniel Pipes's critique.

In undertaking our analysis of the options available to Israel toward a settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian crisis, we at the Jaffee Center did not try to tackle the overall context of the Arab-Israeli dispute. We recognize that what we have produced is seriously constrained by virtue of that fact. At the same time, I disagree with the tenor of at least one of the strands of Professor Pipes's criticisms. As we see it. over the past 10 years or more, there has been a trend among the Arab states whereby an increasing number have come to terms with Israel as a political entity that has to be dealt with politically. This is one of the root factors of the intifada - the feeling of the Palestinians in the occupied territories that they will not find salvation in the Arab-Israel conflict, that most of the Arab world is no longer prepared to wage war for their cause, and that they must do something on their own.

Of course, the peace with Egypt was the most striking event in this trend, but, as was noted, Israeli coexistence with Jordan has been fairly stable for an even longer period than the accord with Egypt. In effect, it is only Syria, among the countries surrounding Israel, that maintains a general war footing. I don't dispute the assessment that at present Syria has no desire to strike a peace agreement with Israel. The point is, though, that the intifada signifies, at least in part, the communalization of the Arab-Israeli conflict. It is now less an interstate conflict, with the very important exception of Syria, and more a communal confrontation between Arabs and Jews in historic Palestine, Eretz Yisrael. In a sense, the intifada has returned us to pre-1948 Palestine.

Clearly, a settlement with the Palestinians does not end the conflict. However, a successful and stable settlement would serve further to isolate Syria. While we agree that we cannot today effect a peace agreement between Israel and Syria, we are certainly bidden to do our best to resolve this newly-raging intercommunal aspect of the quarrel, in order better to isolate the Israeli-Syrian conflict and thus be in a more advantageous position to tackle it somewhere down the line.

Surely Professor Pipes would not dispute the contention that if we could attain a stable settlement with the Palestinians. it could only be for the good of the long-term Israeli-Arab peace process, particularly as it concerns Syria. This is at the heart of the matter: Given the fact that a settlement with Syria today seems a virtual impossibility, and given the present (necessary) preoccupation with the Jewish-Arab communal conflict in Palestine, what are we then to do? Nothing? Or should we not take steps to tackle that conflict which perhaps lends itself to some kind of solution now. It seems to me that a Palestinian settlement would provide a more congenial setting for an ultimate Israeli-Syrian resolution.