Central Asia and the Transcaucasus [also known as the Southern Tier of the former Soviet Union] have for a thousand years been included in the "Persianate zone,"[1]a large cultural area marked by the use of the New Persian language as a medium of administration and literature, by the rise of Persianized Turks to administrative control, by a new political importance for the 'ulama [Islam's rabbis], and by the development of an ethnically composite Islamicate society.[2]

Central Asia and the Transcaucasus [also known as the Southern Tier of the former Soviet Union] have for a thousand years been included in the "Persianate zone,"[1]a large cultural area marked by the use of the New Persian language as a medium of administration and literature, by the rise of Persianized Turks to administrative control, by a new political importance for the 'ulama [Islam's rabbis], and by the development of an ethnically composite Islamicate society.[2]

The Southern Tier had for millennia participated integrally in the development of Iranian culture. The Shahnameh, Iran's national epic, takes place mostly on what later became Soviet territory; the region's cities have a larger presence in the classics of Persian poetry than do those of Iran proper. Bukhara and Marv are two of the oldest and most important cities of Iranian civilization. Samarkand boasts the Gur Emir, Tamerlane's tomb, as well as many other great Islamic structures. Tashkent hosts ancient schools. Medieval figures such as the philosophers Alfarabi and Avicenna, the geographer Albiruni, the poet Ali Sher Navai, and the astronomer Ulugh Beg all lived in what we term the Southern Tier.

The Turko-Persian tradition developed in the Seljuk period (1040-1118) and reached its fullest florescence in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, when it prevailed in an area stretching from Anatolia to southern India, from Iraq to Xinjiang.[3] The Ottoman, Safavid, Chagatay, and Mughal empires all subscribed to this civilization. Their prestige caused it to spread even beyond their boundaries, for example, to Hyderabad in southern India. The Turko-Persian tradition declined in the eighteenth century, when Europeans began to encroach and land trade declined. Still, Persian remained the language of culture in the Central Asian cities until the Russian Revolution.

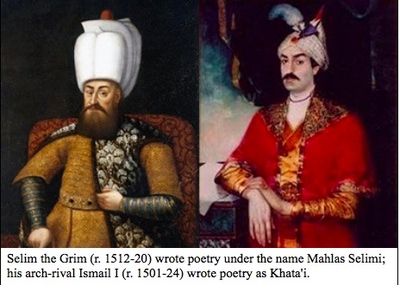

Islam set the parameters in the Persianate zone, Turcophones ruled, and Iranians administered. As this implies, each of the three classical languages of Islam had a distinct function: Arabic belonged to religion; Turkish to the military; and Persian to administration, polite society, and the arts. In short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers. This mix led to unlikely juxtapositions: for example, shortly after 1500, the Iranian ruler Shah Isma'il wrote poetry in Azeri Turkic (under the pen name Khata'i) while his Ottoman counterpart in Istanbul wrote poetry in Persian.

Islam set the parameters in the Persianate zone, Turcophones ruled, and Iranians administered. As this implies, each of the three classical languages of Islam had a distinct function: Arabic belonged to religion; Turkish to the military; and Persian to administration, polite society, and the arts. In short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers. This mix led to unlikely juxtapositions: for example, shortly after 1500, the Iranian ruler Shah Isma'il wrote poetry in Azeri Turkic (under the pen name Khata'i) while his Ottoman counterpart in Istanbul wrote poetry in Persian.

The elites had much in common, from education to home life to styles of dress. But that was not all, as Robert L. Canfield of Washington University in St. Louis explains:

People on many levels of the society had similar notions about the ground-rules of cooperation and dispute, and in other ways shared a number of common institutions, arts, knowledge, customs, and rituals. These similarities of cultural style were perpetuated by poets, artists, architects, artisans, jurists, and scholars, who maintained relations among their peers in the far-flung cities of the Turko-Persian Islamicate ecumene, from Istanbul to Delhi.[4]

Today. The Southern Tier's connections to Iran would seem to be moribund, overtaken by the delimitation of nation-states, Russian colonization, the Soviet experiment, and the Islamic Republic. But they are not: on both sides of the old Soviet border with Iran, the Turko-Persian tradition lives on.

On the northern side, the Turko-Persian tradition remained a source of pride and hope through seven decades of Soviet rule. In 1967 Olaf Caroe, the British administrator and author, explained that "it would be a profound mistake to imagine that the Sovietization of Central Asia and its populations has wiped clean the earlier drawings on the slate."[5] In 1990 Graham Fuller reiterated the point: "the Persian legacy still runs deep in those republics, profoundly shaping their basic culture."[6] Ex-Soviet Muslims have various connections to Iran. Tajiks share with it ethnic and linguistic bonds; Azeris share the Twelver Shi'i religious tradition; Armenians look to it for a potential balance to the Turcophones; and the whole region celebrates Nowruz (the Iranian New Year's festival in March). Much else—music, cuisine, crafts—is also similar.

Today, dispirited by the devastation about them, many ex-Soviet Muslims see Persianate culture and Iran as sources of hope. Symbolic of this, the Tajiks have replaced a statue of Lenin with one of the poet Ferdousi, author of the Shahnameh. Turkmenistanis considered changing their currency unit to the dinar or tuman, though they eventually settled on the manat. Turkmenistan's President Saparmurad Niyazov told the foreign minister of Iran that he was "personally interested" in learning Persian and would facilitate its teaching in his country.[7] On a visit to Iran, Kazakhstan's Minister of Culture Yerkegeliy Rahkmadiyev referred to the two countries' thousand-year relations and declared, "We consider Iran as our own home."[8]

While today's republics have won a utilitarian acceptance, the old khanates of Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand live on in the imagination. The Great Ariana Society in Tajikistan advocates a Greater Khurasan, which would incorporate a Persian-speaking belt from the far end of Afghanistan to the Persian Gulf. Graham Fuller speculates that such a unit could become a counterpoise against a Turcophone belt to the north.[9]

On the Iranian side, too, the Turko-Persian tradition survives. Government officials are generally cautious in their public statements, disclaiming interest in political influence, seeking only a softer kind. According to Foreign Minister 'Ali Akbar Velayati, "the export of revolution means the export of culture and ideas, no more."[10] As a sign of the kind of influence Iranians hope to have, Velayati himself delivered a lecture at the Turkmen Academy of Sciences on the poet and thinker Mahdum Kuli. President Hashemi-Rafsanjani contented himself with bland statements. "The newly independent countries to the north are very dear to us," he declared in late 1992.[11]

Still, indelicate expressions—betraying Iranians' excitement—sometimes get articulated. Velayati spoke of Central Asia's "Iranian identity" and noted that it is impossible to look at the region "without making reference to Iranian culture and to the Iranian language."[12] The religious leader of Isfahan, Ayatollah Taheri, held that "some of the newly independent republics of the former Soviet Union do not agree to the ignominious Turkmanchai Treaty between Iran and the former Soviet Union [actually Russia, in 1828] and consider themselves part of Iran and regard the esteemed leader [Khamene'i] as their own leader."[13] An Iranian journalist explains this impulse: "In our heart of hearts, we know that Azerbaijan and Turkmenia [Central Asia] were once part of the Persian empire."[14] Some Iranians explicitly say as much; Sarhadizadeh, a former minister of labor, predicted that independent Azerbaijan would eventually "become part of Iran."[15] The prayer leader of Mashhad echoed, "The Treaty of Turkmanchay expired several years ago, and these countries are now parts of Iran."[16]

Interestingly, Iran's political "moderates" articulate these dangerous dreams more than its "radicals." That's because the radicals have only Islamic aspirations, while the moderates have Persian nationalist ones as well.[17] For the latter, Shahram Chubin notes, the new states "could in theory become a new constituency or audience, widening the strategic depth of the Islamic republic and deepening its base."[18] Powerful elements within Iran, in short, appear to want to create a sphere of influence that includes Azerbaijan and Central Asia.

In asserting their claims, these Iranians dismiss Turkey's claimed connections to Central Asia and Azerbaijan. Iran's deputy foreign minister reacted with scorn when asked about possible rivalry between Turkey and Iran in the area: "What rivalry? Turks have nothing in the area but local idioms close to Turkish. History, civilization, culture, literature, science—everything is Iranian."[19]

Daniel Pipes is director of the Middle East Forum. This article is excerpted from "'The Event of Our Era': Former Soviet Muslim Republics Change the Middle East" in Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, ed. Michael Mandelbaum (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1994), pp. 79-82.

[1] Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), vol. 2, p. 293. |

[2] Robert L. Canfield, "Introduction: The Turko-Persian Tradition," in Robert L. Canfield, ed. Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 6. |

[3] Just as Europe has for centuries been divided into the Latin and the Germanic cultural zones, with almost no movement in boundaries, so the Muslim world has been divided into Arab and Turko-Persian components. In this sense, the Iraq-Iran border resembles the French-German border. |

[4] Canfield, "Introduction," pp. 20-21. |

[5] Olaf Caroe, Soviet Empire: The Turks of Central Asia and Stalinism, 2d ed. (London: MacMillan, 1967), p. 31. |

[6] Graham E. Fuller, "The Emergence of Central Asia," Foreign Policy, Spring 1990, p. 50. |

[7] Islamic Revolution News Agency, 30 January 1993. |

[8] Islamic Revolution News Agency, 17 June 1993. |

[9] Fuller, Central Asia, p. 66. |

[10] Quoted by V. Skosyrev in Izvestiya, 9 October 1991. |

[11] IRIB Television, 21 October 1992. |

[12] The Middle East, March 1993. |

[13] Kar va Kargar, about 25 February 1992, quoted in Patrick Clawson, Iran's Challenge to the West: How, When, and Why (Washington, D.C.: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1993), p. 42. |

[14] The Christian Science Monitor, 23 September 1991. |

[15] 6 September 1991, quoted in Turkish Daily News, 15 January 1992. |

[16] Mullah Abaii, quoted in Mohammad Mohaddessin, Islamic Fundamentalism: The New Global Threat (Washington, D.C.: Seven Locks Press, 1993), p. 79. |

[17] On this difference and its implications for Iranian foreign policy, see Clawson, Iran's Challenge to the West, chapter 1. |

[18] Shahram Chubin, "The Geopolitics of the Southern Republics of the CIS," The Iranian Journal of International Affairs, Summer 1992, p. 318. |

[19] Quoted in George I. Mirsky, "Central Asia's Emergence," Current History, October 1992, p. 337. |