The Heroic Age and Its Aftermath

American officials currently engaged in Arab-Israeli diplomacy often look back to the 1970s with wistfulness and a touch of envy. Yes, that was a difficult time, what with two oil embargoes, overbearing oil potentates, and a general sense of America in decline. But it was also an heroic age, the heady years when American diplomats achieved some of their greatest successes: Kilometer 101, Sinai I, the Syrian-Israeli disengagement, Sinai II, Camp David, the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, the 1981 PLO-Israel tacit disengagement, and the PLO evacuation from Beirut.

The golden era began mere days after the conclusion of the October 1973 war; at its peak, it starred Henry Kissinger shuttling between Jerusalem, Cairo, and Damascus, then Jimmy Carter holed up in the Maryland woods with the leaders of Israel and Egypt. The era ended abruptly in March 1979 with the signing of an Egypt-Israel peace treaty on the White House lawn.

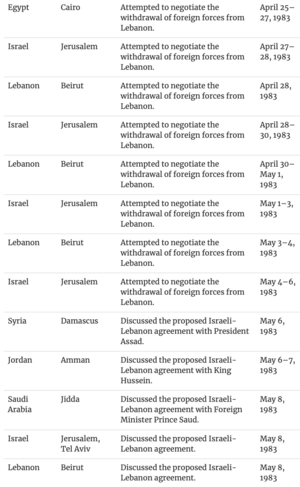

The travels of U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz to the Middle East in April-May 1983. |

Although Shultz's exertions rivaled any of Kissinger's, his travels tend to be forgotten now because the accord they produced, known as the May 17 Agreement, was abrogated within the year. In the phrasing of the time, Shultz had been "burned." This early failure of his Middle East ambitions had major implications for the years to come; his first year as secretary of state taught Shultz a healthy respect for the complexities of the area, and he withdrew from Arab-Israeli diplomacy.

Ironically, the next four years were some of the best ever for the U.S. government in the Middle East. Arguably, at no time since Washington became a major player in the region during World War II had its policy toward the Arab-Israeli conflict been so stable and successful. Finally, it seemed, Washington had realized that its strength lay in alliances with the democratic states of the region, Turkey and Israel in particular, and not with an exotic range of despotic presidents, kings, and emirs. For once, the ever-volatile relationship with Israel attained maturity; no longer did the usual problems cause crises. Gone was Gerald Ford's "reassessment" and other ups and downs. Better yet, American officials had seemingly learned that the Arab-Israeli conflict was not the only problem in the Middle East, nor even the largest or most pressing.

The Turn to Palestinianism

Alas, this era of stability and vision came to an end in mid-1988 following two developments: the outbreak of the Palestinian intifada in December 1987 and King Hussein of Jordan's renunciation of claims to the West Bank in July 1988. Shultz made five trips to the Middle East in 1988 and used them to try out a new tack; rather than deal with the states, as in his previous efforts, he focused on the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the actor widely recognized as the legitimate claimant for Palestinians.

These actions culminated five months later in the opening of a U.S.-PLO dialogue. Shultz left office in January 1989, but he bequeathed that nascent dialogue to his successor, James Baker, including its reversion to the old tension-filled relationship with Israel and hoary illusions about what the Arab governments can do for the United States.

And so, trying to bring the PLO into a working relationship with Israel remains today the primary focus of Washington's diplomacy in the Middle East. It defines the Bush Administration's efforts in the "peace process." But the "process" is completely stalled because the PLO consistently demands to rule the whole territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, if not more. To the general frustration, the peace process has turned into an irrelevant stripped-pants talkathon; Yasir Arafat even threatens to break off talks with the U.S. government – a startling development, given how long and hard he worked to get them established. The main action increasingly appears to be on the ground – the battles taking place in Lebanon, the quiet murder of "collaborators" on the West Bank, and the evident ability of Israelis to live with the intifada.

Looking ahead, there is every reason to expect the American government's frustrations to continue so long as President George Bush and Secretary of State Baker act on the basis of two dubious, if not downright false, notions. When it comes to means, Washington assumes that the Palestinian-Israeli dimension is the key to the conflict; on the matter of ends, it assumes that a compromise solution between Israelis and Palestinians is possible. So long as the administration begins with these notions, its diplomacy is likely to go nowhere. But should it drop them, the U.S. government will again have an important role in the Middle East.

Washington's position is premised on moral equivalence. It calls on each side to give up its maximalist position and it sees the solution lying somewhere between Israeli and PLO positions. Moral equivalism is pernicious, for it leads to a slitting of the difference regardless of the merits of the case. This even-handed approach holds obvious attractions to diplomats but it leads to a slippery slope in the direction of amoralism.

As ever, Washington doggedly pursues that strange beast known as the peace process, hoping to bring Arabs and Israelis to terms. But the years have left this effort behind. Israelis and Palestinians humor the Americans because no one wants to forfeit their good will, but most everyone in the Middle East knows that the effort is hopeless, and that the whole drama is a sham.

Daniel Pipes is director of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and author of Greater Syria (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).