Two Priorities

Two concerns dominate the foreign relations of Saudi Arabia: preserving the kingdom and promoting Islam. The first takes top priority, for the Saudi oligarchs recognize the extreme fragility of their regime; Islamic concerns usually inspire the few activities not directly concerned with staving off revolution or invasion. These two themes have guided Saudi policy for decades and may be expected to determine their actions in the foreseeable future.

Saudi obsession with self-defense and security is well grounded, for the kingdom sits atop the largest known oil reserves in the world; in 1981. sales of oil provided the government with a virtually free income of about $100 billion. This is the largest windfall in human history – more remarkable yet, it requires no Saudi participation. Foreigners locate, produce, refine, transport and consume the oil. The principal challenge to the Saudis – besides figuring ways how to spend it all-is retaining control over this singular source of wealth.

Internally, the tribes and regions conquered by lbn Saud between 1901 and 1925 have still not been fully integrated into the life of the kingdom. Shi'ites in the eastern provinces, the one significant minority in the country, suffer from government discrimination; this is probably what prompted the violent demonstrations in late 1979. Super-zealous Muslim elements who reject all contact with the West threaten to rebel; the siege of the Mecca mosque in November 1979 underscored the seriousness of their intent. Westernized urbanites, to the contrary, reject the conservatism of the regime and favor a more progressive government policy. Migrant workers, now two million strong and growing, resent the fact that they do most (about three-quarters) of the work but receive few benefits; they might explode at any time.

Externally, the Saudi government fears poor Arab and Muslim states whose cultural and religious ties give them claim to some portion of Saudi wealth, but who receive a paltry share of it. They increasingly resent the enormous gap between Saudi opulence and their own poverty; at any point, they may threaten violent action to win a better deal. Radical Middle Eastern states such as South Yemen aspire to topple the reactionary Saudi government. Activist Muslims in Iran, pointing to the entrenched and formal nature of Islam in Saudi Arabia, call for an overthrow of the regime in favor of a true Islamic government. Israel has the ability to devastate Saudi oil facilities, and the great powers could attack Saudi Arabia and take control of its oil production at any time.

The Saudis are doing their best to build up a military force; in fiscal year 1981-82 they will spend over $30 billion on defense, per capita six times what the Reagan budget calls for. Immense "military cities" are going up in remote deserts. the finest weapons from the American arsenal are pouring in, and thousands of foreigners are coming along to service and use them. Despite these efforts, the small size of the Saudi population (between three and seven million) and its lack of skills (less than a quarter are literate) restrict the armed forces' ability to defend the kingdom from its most likely foes. In the words of the Saudi oil minister, never before "has a country had such a valuable resource and been so ill equipped to defend it." For these reasons, the government conducts an especially cautious foreign policy, dedicated above all to preserving the status quo and to fending off hostile elements.

Exerting Influence

Just as oil makes the Saudis tempting prey, so it provides them with the instruments for their defense. Like other super-rich oil states, Saudi Arabia exerts its will in three principal ways: selling oil, purchasing goods and services, and distributing money.

During times of tight oil supplies, a willingness to sell oil. even at ever higher prices, is a weapon in the OPEC arsenal. Iranian supplies to Israel, for example, made up a crucial part of their alliance before 1979 and the cut-off of oil marked its demise. Saudi Arabia increased its diplomatic leverage through the 1970's by steadily expanding its oil output; it began the decade producing 3.5 million barrels a day and ended it with over 10 million. The threat of an embargo kept oil companies docile and reduced their resistance to repeated price increases; and Arab talk of supply cutoffs resulted in dramatic changes in the policy of West European states toward Israel after 1973.

The purchase of goods and services provides OPEC members with a yet more powerful tool of state. Saudi leaders acquired staggering quantities of armaments, infrastructure material, and consumer goods; they employ millions of foreigners as manual laborers, professionals, and soldiers. Further, Riyadh pays premium prices, so its contracts have special appeal. Businessmen and politicians have repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to acquiesce to Saudi political demands if that wins contracts.

The lure of free money also exerts great influence. As many other sources of financial aid dried up during the 1970's, the Middle East oil exporters loomed ever larger as philanthropists. Poor and rich countries besieged the OPEC members with requests for help: inventors, venture capitalists, universities, charitable societies, and indigent rulers beat a path to Riyadh. Aware of Saudi biases, many slanted their statements to win Saudi support. Idi Amin had the audacity to stress his Muslim identity to the Saudi princes and this won him funds for Uganda; after his overthrow, they granted him asylum.

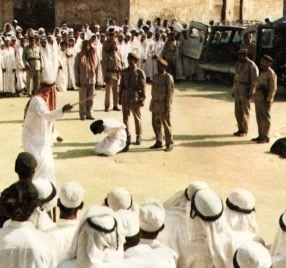

The influence that Saudi Arabia now exerts was vividly demonstrated in the spring of 1980 when it tried to stop the showing of Death of a Princess, a British film about the 1977 execution of two Saudi lovers, a royal woman and a common man. The film follows a journalist as he pieces together facts about the fate of the couple. He finds no firm evidence, but what he does turn up paints an unflattering picture of Saudi society. Although the Saudi government reacted to the movie by calling it an "unprincipled attack" on Islam, it was nothing of the sort; execution of the lovers was done in accordance with tribal custom, not Islamic law.

Despite the innocuousness of this film, the Saudis managed to apply considerable pressure against its screening. In Great Britain (which imports little petroleum but counts on winning petro-contracts), the Foreign Office announced "profound regrets" for the film's insults. Then the foreign minister, Lord Carrington, personally apologized for the "understandable offense" it caused Muslims. As the Saudi Cabinet "studied" economic ties with Britain, the British government pressured the film makers (unsuccessfully) to tone down the offending scenes. Subsequent estimates put U.K. trade losses at nearly $600 million due to the showing of the movie.

In Turkey, Saudi pressure suppressed publication of a photo-novel about the couple's execution. New Zealand television withheld screening Death of a Princess for overtly political reasons. It announced that expected damage to ties with Saudi Arabia far outweighed the merits of the movie. Even the Dutch government tried to prevent its showing. During the height of this controversy, the Saudi government signed a contract with Denmark permitting the Saudis to cancel oil shipments should the Danish government tolerate activities detrimental to Saudi interests (and the Saudis would decide which those were).

In the United States, Mobil Corporation ran ads urging "the management of the Public Broadcasting Service [to] review its decision to run this film and exercise responsible judgment in the light of what is in the best interest of the United States." The acting secretary of state took the unprecedented step of conveying a Saudi letter of protest to PBS. Meanwhile, leading congressmen "accused PBS of showing poor judgment in deciding to show the film." As a New York Times editorial pointed out, these governmental expressions of concern for Saudi Arabia contrasted with the treatment Turkey received a few years earlier when it "protested the showing of Midnight Express, alleging the film gave a lurid picture of Turkish law. But there were then no protesting advertisements and no members of Congress ready to oblige by encroaching upon the Bill of Rights."

Keeping the Lid On

Money cannot buy friends but it does rent allies. Saudi leaders have effectively used their oil royalties as a tool of diplomacy to create a congenial political climate in the Middle East. On the Arabian peninsula, they funded both Yemeni states to wean them away from radicalism and win co-operation with Saudi interests. This policy had spectacular results in North Yemen, which became a virtual client state of Riyadh after 1968; even the Soviet-oriented leadership in South Yemen ended its overt anti-Saudi policies in 1976. On the east coast, Saudi efforts led to the creation of the Gulf Cooperation Council in early 1981, bringing all the sheikdoms of the Persian Gulf into a proto-military alliance dedicated to the status quo.

Similar defensive measures mark Saudi activities in intra-Arab affairs. They helped King Hassan of Morocco fight rebels backed by Algeria and Libya in the Western Sahara, propped up Ja'far Numayri's regime in the Sudan, and helped bring Iraq from its isolation back into the mainstream of Arab politics. The Saudi leaders always prefer to side with the majority of Arab states; they broke relations with Egypt over its peace with Israel. Still, they were careful not to overly provoke Sadat; most money banked in Cairo before 1979 remained there and some aid to Egypt may have continued after that date. Saudi efforts to end the Lebanese civil war in 1976 brought together all Arab states involved in that conflict and led to a reduction in hostilities. Riyadh has consistently worked to heal rifts between Arabs, believing that consensus in the region protects the kingdom from the risks which follow from conflicts between its neighbors.

For similar reasons, the Saudis encouraged negotiations between Iraq and Iran after the outbreak of war in September 1980. Hostilities so close to home threatened to disrupt the precarious world of Saudi commerce and its monarchy. Arab loyalties only partially explained their tilt toward Iraq, for Iranians after 1979 spread a revolutionary doctrine of Islam, urging Muslims to overthrow hypocritical Muslim leaders. This message particularly challenged the Saudi rulers; they rely heavily on Islam for legitimacy, yet the laxness of their private observance is widely notorious. The provocative and chaotic rule of the mullahs in Teheran presented special dangers to the Saudi regime; since the Shah's overthrow, it has consistently opposed Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers.

Washington and Moscow

Saudi leaders explain their pro-American and anti-Soviet alignment with reference to Islam; as good Muslims, they must oppose the atheistic doctrines of communism. But this is facile and inaccurate. While Islam and communism do contradict each other in certain ways, they match each other in others, so that some dedicated Muslims consider Marxism an excellent complement to Islam; the Mujahidin-i Khalq in Iran exemplify this thinking. More commonly, however, staunchly Muslim. leaders such as Col. Qaddafi and Ayatollah Khomeini see liberalism and communism as variant strains of Western culture and dislike them about equally. From a Muslim perspective, these two ideologies resemble each other far more than Islam, which fits well with neither of them. Most Muslims therefore align with East or West according to temperament and circumstance, not because they prefer one ideology to the other. The imperatives of Islam offer almost no guidance here; choosing a great power to side with is strictly a matter of tactics in most cases.

Looked at this way, Saudi alignment with the U.S. makes good sense, for Riyadh feels more threatened by the Soviet Union than by the United States. This does not mean that the latter does not threaten, but that it poses a lesser danger. The United States is, after all, the first republic in modem history, a democratic nation which enshrines free speech and separation of church and state in its constitution, a society which celebrates open culture. These characteristics are anathema to the Saudi leaders who disdain American morality and ways of life. They fear contamination by it and therefore attempt to insulate their kingdom from the Americans who work in the country by isolating them in gilded ghettoes remote from the local population.

But United States policies support the status quo in the Middle East while the Soviet Union seeks to disrupt it. The Russians support radical change, aiding socialists and anti-monarchists. An attempt to seize control of the Persian Gulf at some point in the future would threaten the only basis of Saudi wealth. Saudi leaders value the United States because it helps maintain the status quo, not because they admire its principles; they resist the Soviet Union because it looks more dangerous to them.

As a result, Saudi leaders have opted for cooperation with America versus the Soviet Union. They helped arm the mujahidin in Afghanistan against the communist regime in Kabul, they aided the Somali government as it moved away from the USSR, and even sent support to distant anti-Soviet causes, such as that of UNITA in Angola.

Saudi and American policies diverge most sharply over Israel, a nation whose very existence the Saudis oppose. While Jewish control of the area offends their Muslim sensibilities (for reasons discussed below), they also see Israel as a destabilizing force whose military power menaces them directly and whose existence provokes increasing radicalism in the area, threatening them indirectly. Further, Saudi leaders emphasize the socialist content of Zionism and link it to Marxism, making opposition to Israel fit into their general campaign against communism.

In contrast, American administrations have viewed Israel as a reliable ally in the effort to resist Soviet encroachments in the Middle East. Americans tend to doubt that Israel harbors aggressive plans against Saudi Arabia; they usually blame the Arab countries – not Israel – for conditions leading to an epidemic of radicalism. Americans do not share the Muslim antagonism to Jews running a small portion of the Middle East. These large differences on Israel will continue to trouble U.S.-Saudi relations; yet their community of interest on other issues assures that the two countries will remain tactically allied for some time to come.

The Saudi Alternative

In the age of Nasser and the heyday of the Ba'ath party, 1956-67, Saudi Arabia and the other conservative Arab monarchies faced the challenge of radical pan-Arabism. This doctrine called for the overthrow of "reactionary" regimes, the sharing of oil wealth, and the elimination of intra- Arab boundaries. Pan-Arabism forced the Saudis to the defensive for over a decade, then Israel's stunning defeat of the Arab armies in June 1967 discredited Nasserism, exposed the hollow promises of pan-Arabism, and forced the "progressive" states to depend on subsidies from the conservatives. The 1973 war accelerated this trend. A quadrupling of the price of oil and an oil embargo declared against Israel's supporters further enhanced Saudi clout. Radical pan-Arabism had failed, oil reigned supreme, a new age dawned and the Saudis were its sponsors.

Since 1973, the Saudis have offered a form of moderate Arabism which threatens neither monarchism nor petro-wealth. This status quo program calls for respect of existing borders, close cultural and political ties between Arab states, and a modicum of financial sharing between them. Egypt has completely abandoned its old ways and other states (Syria, Iraq, North Yemen) have come to terms with the Saudi order – only Libya has moved in the opposite direction.

The Wahhabi Model

Like Arabism, Islam sanctions either change or the status quo, depending on its practitioners. Khomeini exemplifies the populist strain of Islam. In the name of justice. he rips down the established order and attempts to implement a vision of radical reform. Qaddafi and the besiegers of the Mecca mosque show similar intent. In contrast, Saudi Islam resembles its Arabism, calling for the recognition of existing borders and regimes, justifying the existing distribution of oil wealth, decrying any dealings with godless communism. In so far as the Saudis can mold Arabs and Muslims into a harmonious bloc, their own position grows stronger.

To this end. they promote their own kingdom as a model for Muslims to emulate. Saudis fund a wide range of Islamic activities which make their ideas accessible to the whole Muslim world. They established many organizations covering virtually every aspect of Muslim life: politics, warfare, economics, finance, justice, education, communications, science, health, and sports. In addition, they help organizations which bring together political leaders from minority Muslim communities, students and religious authorities. Saudi money also pays for conferences, exhibits and publications which survey Saudi views on Islam to Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Funding and hosting these activities gives them an opportunity to participate in the organized religious life of other Muslim countries. Their status as protectors of the two holy cities (Mecca and Medina) makes such Saudi involvement fairly accepted.

Yet there is more than this to Saudi Islam. These are the heirs of Wahhabism, the uniquely strict Islamic doctrine which originated in 18th century Arabia with the teachings of Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab (1703-91). In the attempt to recreate the original Islamic society of the Prophet Muhammad's time, he stripped Islam of the accretions it had gathered over the course of a millennium, especially the worship of saints and lax application of regulations.

Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab allied in 1745 with Muhammad ibn Saud, a nearby tribal chief, and together they created a powerful new state in central Arabia. After conquering neighboring tribes, they attacked southern Iraq and Mecca; though unable to hold these regions, such a rapid expansion showed unmistakable intent to reform Islam beyond Arabia. But the moral appeal of Wahhabism reached much further than its armies; simple and powerful doctrines affected Muslims visiting Arabia on pilgrimage from all over the Muslim world and they carried its influences back home. Important Islamic movements at least partially inspired by Wahhabism subsequently occurred in northern Nigeria, Libya, Egypt. Syria, West India, Bengal, Sumatra, and Chinese Inner Asia.

The Wahhabi state disappeared twice during the 19th century but was re-established a third time in 1901. (Called this time the Saudi state, the change in name signaled a shift in power from the religious family to the tribal one.) Although the kingdom was one of only a few non-Western states to retain complete independence from European control. it had nothing worth calling a foreign policy until after the 1973 war, when it emerged as a key factor in the Middle East. Even after that date Saudi concerns still revolved primarily around self-preservation but some indications of an outward-looking policy can be discerned.

An Outward-Looking Policy

Given the Saudi heritage, that has not surprisingly involved Islam. No longer interested in taking direct control over other Muslim lands, the Saudis contented themselves with support for groups striving for goals they endorsed.

Broadly speaking, these divided into two groups, according to the country's Muslim population, whether autonomous or under the control of non-Muslims. Where Muslims ruled, Saudi funding went to movements interested in applying Islamic laws – those family regulations, penal codes, commercial regulations, etc. Noteworthy examples include the Ansar (descendants of the Mahdi's supporters) in the Sudan, the Muslim brethren in Egypt and Syria, the National Salvation Party in Turkey, anti-Bhutto forces in Pakistan, and pro-Islamic ones in Bangladesh.

Where Muslims live under non-Muslim rule, Saudi Arabia supports groups trying to form Muslim independence: the Moro rebels in the Philippines, Patani rebels in Thailand, Eritreans and Somalis in Ethiopia, mujahidin in Afghanistan. Palestinians against Israel. Other groups are struggling for increased political rights: the Kashmiris in India, Turks in Greece, Rohingyas in Burma. The Saudis are especially active in publicizing the little-known cases where they feel Muslims are mistreated.

Contrast with Libya

Concern with preserving the status quo makes perfect sense for Saudi leaders. Their extraordinary wealth and manifest inability to protect themselves make the regime a ripe target. Sensible as it is, however, defensiveness is not inevitable; Saudi rulers do have a choice, as a comparison with the foreign policy of Libya under Col. Muammar Qaddafi makes clear. Since coming to power in 1969, Qaddafi has sought out turmoil and change as much as the Saudis have worked for peace and stability. Qaddafi made a reputation as the premier supporter of terrorism and the leading gadfly of international affairs, meddling gratuitously around the globe, invading Chad, using Billy Garter, helping to build the "Islamic bomb," running around in the Philippines. He is the only pan-Arabist left in power. Domestically too, he experiments with novel forms of economic systems and political structures. Rarely does Qaddafi give the impression of sharing the worries of his Saudi colleagues.

What accounts for the stark contrast between these two regimes? They share similar resources – much money, little manpower, fewer skills – yet one is fearful and the other charges into the unknown. Temperament explains some differences: Qaddafi took power when only 27 years old through a coup d'état, while Saudi leaders inherited their kingdom at much more advanced ages. Qaddafi rules despotically, Saudi leaders govern by consensus; Libya has a tyrant, Saudi Arabia a committee. Qaddafi confidently believes that he represents the wave of the future and promotes his ideas by such means as coining neologisms (jamahiriya, "the state of the masses") and writing pamphlets (The Green Book). Saudi leaders fear the future, aware that their monarchy and social order are anachronistic. The cautious, fearful quality of Saudi foreign policy does not follow automatically from its vulnerable wealthiness; it might pursue more aggressive policies were the political system different. No less than other states, Saudi Arabia's foreign policy reflects its domestic structures; its meekness derives from perceived weakness.

Daniel Pipes, affiliated with the University of Chicago, is the author of Slave Soldiers of Islam (Yale University Press, 1981), An Arabist's Guide to Egyptian Colloquial (soon to be published by the Foreign Service Institute) and is currently at work on a study of Islam and modern politics. He has written about the Middle East and Islam for the national press, and his articles have appeared in Commentary, The New York Times and Business Week. He is a graduate of Harvard and did advanced graduate work at the University of Cairo.