SUNNIS

The overwhelming majority of Muslims – some 93 percent – adhere to non-sectarian Islam. Known as Sunnis (sunna = "beaten path"), they predominate in nearly all the Muslim regions. Virtually no communities of sectarian Muslims live in Morocco, the savannah and desert lands of West Africa, or in Egypt, Central Arabia, Bengal, China and Southeast Asia.

In modern times, little distinguishes one Sunni from another. Until the nineteenth century, the four madhhabs (systems of jurisprudence, usually translated as "law schools") divided Sunnis and constituted an important part of their identity, but these have almost disappeared from the Muslim consciousness. As European influence grew, Islamic law weakened and its juridical divisions lost most of their importance.

Sufism

Sufi tariqas, the mystically-oriented brotherhoods, retain social and political significance in some places; yet even where strongest, as the Tijaniya is in West Africa or the Bektashiya in the Balkans, they seldom constitute a "branch" of Islam (though the Murids of Senegal provide a striking exception). Instead, they supplement a Muslim's primary allegiance to Islam with a closer, smaller bond. The Sanusis of Cyrenaica in Libya had the strongest grip of any major tariqa in modern times, providing both the Libyan national identity and its ruler, but al-Qadhafi's government has suppressed it since coming to power in 1969.

Wahhabism

Numerous Sunni reform movements have developed during the past two hundred and fifty years, starting with Wahhabism. Its founder, Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab (1703-91) rejected the many accretions Islam had acquired over the centuries and tried to return to the simple faith of the seventh century. This singularly stark and harsh vision of Islam grew powerful in Eastern Arabia and, in a much diluted form, still remains the ideology of the Saudi government. Wahhabism inspired innumerable other movements across the Islamic world, from China and Indonesia to West Africa, some of which, such as the Ansar (descendants of the Sudanese Mahdi's followers) remain politically active today.

Ahmadis*

Modern Sunni Islam has spawned only one sect, the Ahmadis. Its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (c. 1839-1908), an Indian Muslim, began receiving revelation~ in 1876, and in 1890 he claimed to be the mahdi (the figure in Islamic eschatology who initiates the sequence of events which ends the world). His followers split into two groups after his death. The Qadyanis remained true to Ahmad's full claim. The Lahoris denied that he had ever thought of himself as a prophet or mahdi. Ahmadis consider themselves not a sect but regular Sunni Muslims; this, however, is passionately denied by mainstream Sunnis. The movement has not met with any success in the old Muslim lands except for Pakistan, but it has found followings in Indochina and coastal West Africa. Ahmadis are the only group seriously proselytizing in the Christian West, where they emphasize the idea that Jesus survived crucifixion, lived to the age of a hundred and twenty in Kashmir and now lies entombed in Srinagar. Ahmadis number between 500,000 and one million. In 1974, the Pakistan National Assembly ruled that they are not Muslims.

SHI'IS

In the west, Shi'is are occasionally called the Protestants of Islam, an utterly inaccurate description in every way but one: like Protestants, Shi'is have a tendency toward schism and toward breaking into smaller and smaller groups until, finally, some disappear. In short, they share a problem of authority. Of the many Shi'i differences with Protestantism (for example, Shi'ism appeared in the first years of Islam; it does not diverge liturgically in important ways from Sunnism), the most trenchant is this: while Protestants split over arguments about truth, Shi'is split over issues of power. Shi'i groups, that is, began as political factions and then developed into religious movements while Protestant groups did the reverse. In every case where a new Shi'i group emerged, it had a leader; only secondly did it also claim a distinct vision of religious truth.

All Shi'is believe in the special role of 'Ali b. Abi Talib, cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, and of his descendants, the 'Alids. Although Sunnis share with Shi'is a natural affection for the House of Muhammad (even today two Sunni kings, Husayn of Jordan and Hasan of Morocco, claim Muhammad as an ancestor), they deny 'Ali and the 'Alids a special place in Islam. Shi'is have always been in the minority, though they briefly challenged the predominance of Sunnism in the tenth century. Except for the Zaydis (see below), Shi'i political psychology is primarily suited to an opposition role; its tendencies toward secrecy, dissimulation, and martyrdom are hardly appropriate to the religion of rulers.

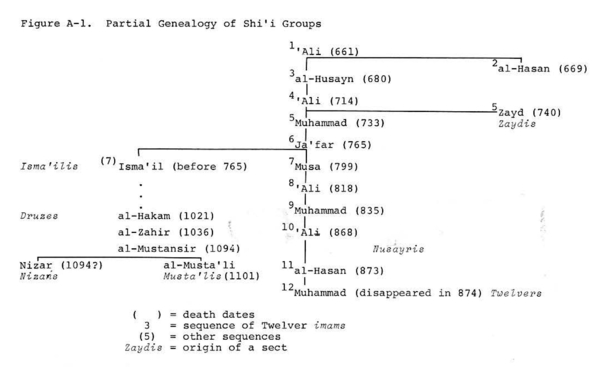

Shi'i groups derive their identities from 'Ali's descendants. The partial genealogy (Fig. A-1) outlines their family relationships.

Partial Genealogy of Shi'i Groups. |

Zaydis

Zaydis are the most moderate, least sectarian of all Shi'i groups. They consider Zayd b. 'Ali b. al-Husayn to have been the fifth imam (supreme leader of the Muslim community in Shi'i terminology). In contrast to other Shi'is, Zaydis view the 'Alids as earthly leaders without divine characteristics. Their imam does not differ very greatly from the Sunnis' caliph. Zaydis have controlled two states, one long ago by the Caspian Sea, the other in Yemen (from about 850 until 1962 - except for a three-century hiatus, 1281-1592). Notables selected an imam from among the most capable of Zayd's descendants, but they often disagreed, causing repeated splits. The last Yemeni imam was deposed in 1962, and lives in London, but still retains spiritual authority for many Yemenis, Zaydis constitute perhaps slightly over half the population of North Yemen where, concentrated in the tribes, they have long formed the military and social (but not economic) elite of the country. They number about three million.

Twelvers (Ja'faris)

Apart from the Zaydis, all Shi'is believe in a sinless and infallible imam and are divided into two main groups: the Imamis and the Isma'ilis. More often known as Twelvers (Ithna'ashariya) or Ja'faris, the Imamis believe in a line of twelve manifest imams which ended in 874; since that time imams have been hidden from most of mankind and will become known to everyone again only at the time of the end of the world (when they will be called the mahdi). In the meantime, religious leaders (mujtahids, led by marja'-i taqlids or ayatollahs) interpret the law on behalf of the hidden imam and direct the community. In contrast to their authority, which derives from God, that of political rulers is considered religiously irrelevant.

An anti-political attitude of this sort was simple to maintain so long as Twelvers were out of power, but since the establishment of the Safavid dynasty, in 1501, Twelver Shi'ism has been the state religion of Iran. Accustomed to centuries of opposition, its leaders have not yet defined their position in a Twelver state ruled by a non-religious leader, and religious authorities are inclined to take political power themselves. Outside Iran, Twelvers lack power: in Iraq, where they make up more than half the population, and in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Lebanon (in Lebanon they are called Mutawalis). Several of these countries, however, recognize the Shi'i madhhab, which diverges little from the Sunni madhhabs (most conspicuously different are the mention of 'Ali b. Abi Talib in the statement of faith and recognition of temporary marriage). Forty million Twelvers make this by far the largest branch of Shi'ism; of these, about twenty-five million live in Iran. Because their imams are hidden, Twelver Shi'is have proved relatively immune to succession disputes and to schisms.

Nusayris*

Two significant Twelver offshoots, lasting to the present day, are the Nusayris and the Shaykhis-Babis-Baha'is. The Nusayris, also known as Alawis* or Ansaris*, broke away from the tenth or eleventh of the twelve imams in about 859. At that time, Ibn Nusayr declared himself the bab ("gateway to truth"), the figure who comes right after the imam in dignity and power. With this authority, Ibn Nusayr proclaimed new doctrines, notably the incarnation of divinity in 'Ali; the holy trinity of 'Ali, Muhammad, and Salman al-Farisi (a freed slave of Muhammad's and the first Persian convert to Islam); and the soul-less nature of women (leading to their abominable treatment by Nusayris). The religion includes many Christian elements, such as the notion of a trinity and the celebration of Christian festivals. In modern times, Nusayris live mostly along the coast of Syria and in nearby regions of Lebanon and Turkey. (The Qizilbashis in Turkey resemble Nusayris closely.) In Syria, Nusayris number over half a million and constitute the largest minority in the country. Between the two world wars the French authorities in Syria favored this community, granting it autonomy in an État des Alouites ('Alawi State) which, however, did not survive Syrian independence in 1944. With French encouragement, Nusayris ('Alawis) joined the army in large numbers and, as a result, today make up a disproportionate element of Syria's officer corps. In addition, they joined the Ba'th party with enthusiasm; its secular nationalism de-emphasized the traditional religious differences dividing them from the Muslim majority. Since 1967 the Ba'th has provided them with a mechanism for ruling Syria; President Asad and his top officials are mostly 'Alawis.

Shaykhis-Babis*-Baha'is*

The other noteworthy Twelver offshoot occurred in the nineteenth century, beginning with the controversial but not clearly irregular teachings of Shaykh Ahmad b. Zayn ad-Din al-Ahsa'i (1753-1826) whose followers became known as Shaykhis (they number about 250,000 today). In 1844, exactly one thousand lunar years after the occultation of the twelfth imam in 874, a Persian Shaykhi, Sayyid 'Ali Muhammad (1819-50) claimed to be the bab, then the mahdi, and finally a prophet in his own right, contradicting the Islamic belief in Muhammad as the final prophet. After 1844, the Bab's doctrines diverged increasingly from those of Islam. In particular, his most sacred writing (the Bayan) abrogated the Qur'an and instituted a large number of new regulations (many, curiously, centering on the number nineteen). Iranian government troops executed him in 1850 as a result of the political unrest caused by his followers, the Babis. Violent persecution succeeded, by 1853, in defusing its activism, but not in eliminating the faith.

Two half-brothers succeeded the Bab, Subh-i Azal and Baha'ullah. Subh-i Azal remained true to the Bab's teachings. His followers, known as Azalis*, number less than 50,000 today. Baha'ullah (1817-90) transformed the Babi doctrine, claiming in 1853 to be the manifestation of God and that his own holiest book (Kitab al-Aqdas) abrogated the Bayan. Living in exile under Ottoman custody,

Baha'ullah's outlook and aspirations broadened; with time he developed doctrines attractive to non-Muslims, especially Occidentals. Baha'ism* advocates pacifism, universal fraternity, racial fusion, and a single universal language. Baha'ism has no cult and became, in effect, a faith for the non-religious. Baha'ullah's descendants have succeeded him, uneventfully, as the sect's leaders until the present day. Baha'is number about a million in Iran, where they have never attained legal recognition and suffer intermittent persecution. Some 10,000 converts in the United States, 3,000 in Uganda, and 1,000 in West Germany provide Baha'ism with important places of refuge outside Iran.

Isma'ilis, or Seveners

Shi'is who believe in Isma'il as the seventh imam are known either as Isma'ilis or Seveners; they have split the most often and present the most intricate picture. They lived in fairly obscure circumstances from the time of their break with the Twelver Shi'is in about 765 until the Fatimids' stunning capture of Tunisia in 909. Sixty years later, the Fatimids conquered Egypt and moved there, establishing one of the richest and most dynamic polities in medieval Muslim history.

Druzes* (Muwahhidun)

One of their kings, al-Hakam (r. 996-1021) behaved in ways so strange that some extremist Isma'ilis thought him divine. Adherents of this new faith, known to the outside world as Druzes and to themselves as Muwahhidun, withdrew from the community of Islam into the hills of the Levant, espousing a secret doctrine known only to a few initiates. Druze leaders rose to local political power in the fifteenth century and still remain an important force in Lebanon. With populations of about 150,000 in both Lebanon and Syria, they form a majority in certain small areas. While the Druze in these two states and in Jordan (where they number 10,000) have recently de-emphasized their withdrawal from Islam in order to fit more neatly into the social and political order, the 35,000 Druze in Israel have openly declared their non-Islamic sentiments by fighting on the Israeli side since 1948.

Nizaris

Al-Hakam's grandson, al-Mustansir, had a contested succession. Some Isma'ilis followed his son al-Musta'li. Others, including the notorious Assassins ("users of hashish," a secret order distinguished by its members' blind obedience to their spiritual leader and their use of murder to eliminate foes) remained faithful to his son Nizar, even though he died without an heir. Modern Nizaris (known as Khojas in India, Isma'ilis in Syria, and Muridan-i Agha Khan in Iran) retain none of the Assassins' fanaticism or violence but live peacefully as merchants and entrepreneurs, and are distinguished by their exceptionally developed community consciousness. In 1834, the Iranian ruler gave their forty-fifth imam the title "Agha Khan," and the British granted him numerous privileges when he subsequently took refuge in India. The Agha Khan is the earthly incarnation of divinity for his followers, who take his word as law. The current imam, Karim Khan, succeeded his grandfather in 1957. Two hundred thousand of his followers live in India and in regions of Africa to which Indians emigrated (Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa); about 100,000 are scattered through the Middle East, in Central Asia, Syria, the al-Hasa province of Saudi Arabia (near Kuwait) and the Yemen.

Musta'lis

The Musta'lis splintered into small groups: Tayyibis, Amiris, Bohoras, Da'udis, Sulaymanis, et al. Unable to maintain sectarian cohesion, they have a history of assimilating with other Muslim groups. To avoid persecution by the Sunnis, the Musta'lis, like most Shi'is, practice dissimulation but, lacking clear leadership, some of them forget the pretense and with time, take the Sunni faith to heart. Highly secretive, they have prevented most of their religious literature from being published. Like the Nizaris they are, for the most part, merchants, mostly the descendants of Indian converts to Islam in India, Burma, Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania; and another branch exists in the Yemen. With their tendency toward schism and secrecy, the history and distribution of Musta'lis is poorly known.

Ahl-i Haqq*

At the far edge of Shi'ism are two small, barely Islamic groups. One, the Ahl-i Haqq (also known as 'Ali-Illahis*), definitely sprang from Isma'ili origins, probably in the fifteenth century. They follow the secret doctrines of Sultan Suhak, including his immensely complex cosmology and tightly organized communal life. Ahl-i Haqq are found primarily in the rural areas of Western Iran and in Syria, Turkey, Central Asia, and India. Known as Alevis* in Turkey, they are frequently confused with Nusayris.

Yazidis*

The second group, the Yazidis, incorporates Islamic elements with those of many other religions, especially Christianity and Zoroastrianism. Its 150,000 or so believers are almost all Kurds, living in northern Iraq, Syria, and eastern Turkey. The secret doctrines and endogamous marriages of the Yazidis have not only helped maintain the community through centuries of persecution but have also prevented the outside world from fully understanding the faith's beliefs and practices.

KHARIJIS

The Ibadis are neither Sunnis nor Shi'is but the only surviving heirs to a division in Islam once nearly their match in numbers, the Kharijis. When Muslims fought over leadership of the Islamic community in the decades after Muhammad's death, the Shi'is insisted that the imam must come from among 'Ali's descendants, the Sunnis allowed the caliph to come from any branch of Muhammad's tribe, the Quraysh, and the Kharijis required no descent at all. Conversely, while Shi'is almost ignored their leader's personal qualities and Sunnis paid them only moderate attention, Kharijis insisted that the ruler have an irreproachable character. They claimed to be ready to follow a virtuous leader even if he were "an Ethiopian slave with his nose cut off." Kharijis applied the same severe standards of morality to ordinary individuals. Anyone guilty of a major sin was no longer a Muslim in their eyes. Here, indeed, are the Protestants of Islam, interested in virtue, not in power or in blood relations.

Khariji groups died out over the centuries, usually in violent ways. Only the most moderate of them, the Ibadis, have survived to the present. Kharijism has dominated in Oman (present population 900,000) since 751 and is the state religion there today. Omanis took Ibadi Islam with them to Zanzibar in the nineteenth century, where several thousand Ibadis still live. Another 150,000 are split between isolated communities in Libya (at Jabal Nafusa), Algeria (in the Mzab desert region), and Tunisia (on the island of Jerba).

Islamic sects have flourished especially well in a rectangular area from the eastern Mediterranean shore to the northwestern border of India. Most sectarians live within this region; two other clusters live along the southern coast of Arabia and the western coast of India. Except for the Zaydis and the Twelvers, no branch has appreciably more than a million adherents and all of them combined constitute only a small minority of Muslims. In contrast to the emphasis here on schisms and cults, Islam is characterized by a catholic unity which allows wide varieties of faith and practice within the Sunni framework.

* An asterisk indicates that a group's adherence to Islam is questioned or rejected by mainstream Muslims.