Jüdische Rundschau: What is your personal story?

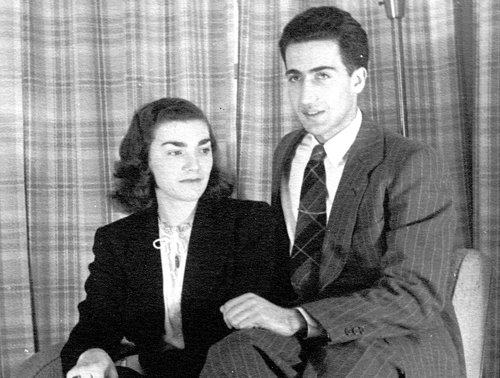

Daniel Pipes: I am the first child of two Jewish refugee families who barely escaped the Nazis from their homes in Warsaw. My parents arrived separately in the United States in 1940 and met at Cornell three years later.

One of the first pictures of Richard and Irene Pipes together, from about 1943 in Elmira, New York. |

Born in 1949, I grew up during the halcyon 1950s in three towns outside Boston. Living in the shadow of Harvard University, I naturally aspired to study there, which I did for both my A.B. and Ph.D. At college, I began as a mathematician and ended, like my father, as a historian. I studied abroad mainly in Cairo but also in Paris, Lausanne, Tunis, Istanbul, and Freiburg im Breisgau.

I taught at several institutions – the University of Chicago, Harvard, the U.S. Naval War College – before realizing that my conservative and pro-Israel politics would render a career in academia a bleak one of perpetual battle. I opted in favor of the more pleasant and productive world of think tanks. That career had one foundation: writing. Almost everything I achieved, from making a salary to building an institution to gaining influence, resulted from writing. I sometimes shake my head in surprise at this and with a sense of great good fortune.

JR: How did you get involved in political issues?

DP: My doctorate concerned the role of Islam in public life; just nine days after receiving my diploma in 1978, Ayatollah Khomeini initiated the Iranian Revolution, transforming my medieval specialization into a valued expertise about current events. Their pace and drama led, almost without my realizing it, to focusing on contemporary history. I entered the world of think tanks in 1986, first at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, then founding the Middle East Forum (MEF) in 1994.

JR: What is your history of engagement with the Arab-Israeli conflict?

DP: I have intensely followed the Arab-Israeli conflict since the Six-Day War in 1967. I began studying the Middle East in 1969 and received two degrees in it. I taught its history at universities and dealt with the region at the State Department. I wrote my first public analysis of it in 1970, and published my first newspaper article on it in 1979. Since those beginnings, I have written about 800 times on the topic and spoken publicly on it at least as often. I first visited Israel in 1966, eastern Jerusalem and the West Bank in 1969, and Gaza in 1976. I resided in the Middle East for four years. I met Yasir Arafat and every Israeli prime minister of the past forty years except one (Yair Lapid).

Yasir Arafat and Daniel Pipes shake hands, Gaza, July 1996. |

JR: What were your sources and inspiration for Israel Victory?

DP: I experienced America's first-ever major military defeat in 1975 not as a soldier in Vietnam but as an active, engaged supporter of the war. As such, I witnessed first-hand how a powerful country loses the will to keep fighting. That personal familiarity with political defeat shaped my views in two ways pertinent to Israel Victory: appreciating the vital role of demoralization, and the means by which it is effected. In brief, if a weak North Vietnam could defeat the mighty United States, surely mighty Israel can defeat the weak Palestinians.

The Israel Victory idea germinated in the battles over the Oslo Accords between 1993 and 2008, an era when Israelis blinded themselves to normal national self-interest. Concluding that the "peace process" had gone deeply awry, I sought from 1997 to apply the lessons of history to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This approach reached full formulation in 2001. It draws in particular on the global experience of victory and defeat, on Revisionist Zionism, and on Israel's defeat of the Arab states.

JR: What do you mean by victory?

DP: Victory takes place when one side to a conflict accepts defeat, accepts that its key war goals are unobtainable. In other words, the loser, not the winner determines when victory is achieved; not understanding this can lead to such errors as George W. Bush speaking under a "Mission Accomplished" banner.

JR: What about rehabilitating the defeated party?

DP: It's a good idea in principle, but only after defeat has been achieved, never before. The American efforts after World War II had great success. Most Palestinians, however, are as intent as ever to destroy Israel and have not accepted defeat, yet they are rewarded as though they had done so. That is as smart as launching the Marshall Plan in Germany in 1942.

Logo of the Israel Victory Project. |

DP: The Middle East Forum, where I am president, launched the Israel Victory Project in January 2017. It fit within MEF's existing approach of "finding the path to victory" against radical and destructive forces in the Middle East. IVP benefited from Gregg Roman, with his activist skills, joining the staff in 2015 and two years later, the coming to office of Donald Trump, with his idiosyncratic approach to policy ("I would love to be able to be the one that made peace with Israel and the Palestinians. I would love that, that would be such a great achievement because nobody's been able to do it").

JR: And the idea for a book?

Adam Bellow of Post Hill Press. |

JR: What were the main obstacles?

DP: Having published some seventy articles on Israel Victory over the preceding quarter-century, it was a relatively easy book to write. First, I collected information from those many pieces. Then, in a process which seems a bit magical in retrospect, in the course of ordering that information it coalesced in new ways, sending me in unanticipated directions, and inspiring original insights.

JR: Please elaborate: what was serendipitous?

DP: The way in which facts and topics came together. For example, I previously had thoughts about Islamic Zionism, meaning the Palestinian creation of a counter-narrative to Jewish Zionism, but these only coalesced in the book. There, I explain, as Zionists articulated a vision of Palestine becoming the Jewish national home, Palestinians turned the same land into a lost Islamic idyll. As Jews returned to the land of milk and honey, Palestinians devised an intense longing for the land of orange groves and olive trees. As Jews established the State of Israel, Palestinians demanded to replace it with a State of Palestine. As Islamic Zionism ascended among Palestinians, this ultimate act of cultural supersessionism and national appropriation acquired a surreal intensity that spewed a toxic loathing for the original Zionism, denying its history and seeking its destruction, as expressed through genocidal rejectionism.

JR: What makes the Palestinian-Israeli conflict unique?

DP: Given their relative strengths, Israeli and Palestinian positions reverse what one expects; Israel should be demanding, Palestinians pleading. One can debate long into the night which of them is the more absurdly inappropriate. The origins of these mentalities go back nearly 1½ centuries when, at the very start of the Zionist enterprise in the 1880s, the two parties to what is now called "the Palestinian-Israeli conflict" developed distinctive, diametrically opposed, and enduring attitudes toward each other.

Zionists, from a position of weakness, making up a minute portion of Palestine's population, adopted conciliation, a wary attempt to find mutual interests with Palestinians and establish good relations with them, with an emphasis on bringing them economic benefits. Palestinians, from a position of demographic strength and great power patronage, adopted rejectionism, a resistance to all things Jewish and Zionist.

Varying ideologies, objectives, tactics, strategies, and actors meant details varied over the next 150 years, even as fundamentals remain remarkably in place, with the two sides pursuing static and opposite goals. Much has changed over time – wars and treaties come and go, the balance of power shifts, the Arab states retreat, Israel gains vastly more power, its public moves to the right – but conciliation and rejectionism remain basically unchanged. Zionists purchase land, Palestinians make selling it a capital offense. Zionists build, Palestinians destroy. Zionists ache for acceptance, Palestinians push delegitimization.

Zionists build, Palestinians destroy: the destruction on Oct. 7 at Kibbutz Be'eri. |

Positions further hardened over time, leaving the two sides ever more frustrated and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict consists of endless, wearisome rounds of violence and counter-violence, neither of which ever achieves its purpose. Palestinians can damage Israel through acts of violence and by spreading an anti-Zionist message, but they cannot prevent the Jewish state from ascending from one success to the next. Israel can punish Palestinians for their aggression, but it cannot quench the rejectionist spirit and its ever-more depraved expressions. That rejectionism is not temporary, does not bend to the pressure of carrots and sticks, and does not moderate over time explains the general inability to understand it or formulate a response to it. The mentality bewilders contemporaries as something hitherto unknown, a new phenomenon that prior experience cannot explain, like the French Revolution or Soviet Russia.

JR: What makes the Palestinian-Israeli struggle so uncompromising?

DP: A mix of Islamic doctrines, alliances, historical legacies, and specific Palestinian features account for this exceptionally enduring radicalism. Islamic ideas of jihad, martyrdom, of Palestine as a religious endowment, and of Jews contribute to the tenacity. External support from great powers (the Ottoman Empire, the British, the Nazis, the Soviets), Arab states, Iran, Türkiye, Islamists, and the global Left have encouraged Palestinians to stick to their genocidal goals. Other factors include: seeing Israel as a latter-day Crusader state; the Middle Eastern traditional of politicide (annihilating a state and scattering or killing its people); the fantasy of a "right of return"; the uncanny ability of leaders to transform military defeats into victories; cartographic ignorance; revolution as a Palestinian career; conspiracy theories; and Israeli timidity. (To unpack these, please see chapter 2 of the book.)

JR: What is wrong with the Israeli approach?

DP: Conciliation contains two failed components, economics and security.

Conflict has an inherently economic dimension. Armed forces normally cut supply routes, impede navigation, establish blockades, impose sanctions, apply embargoes, and starve enemies. But Israeli leaders decided on an opposite approach – to improve Palestinian economic welfare. I call this the policy of enrichment. Enrichment represents the deepest, most powerful, and most enduring of Israeli approaches to its Palestinian foe. It developed at the very outset of Zionism, founded in the naïve assumption that Palestinian economic self-interest would push other concerns aside, that gains from advances in welfare would reconcile Palestinians to Jewish immigration and the creation of a Jewish homeland. From this emerged the Zionist hallmark, the unique idea that the movement's progress depended not on the universal tactic of depriving an enemy of resources, but on the opposite one of helping Palestinians to develop economically. Enrichment did indeed enrich. It also, ironically, boosted rejectionism.

Whereas enrichment reaches back to the misty earliest days of Zionism, placation has a more recent origin, dating specifically to the evening of Sep. 13, 1993, hours after the Oslo Accords' signing. From that date forward, Israeli politicians and security leaders largely ignored Palestinian transgressions, including incitement, illegal construction, and murders, hoping these were transitional bumps on the path to a successful outcome. But placation also failed, also boosting violence and delegitimization.

JR: How does the strategy of enrichment work?

DP: Fearing the impact on Israel of the Palestinian Authority (PA) collapsing, hoping to render Hamas less aggressive, the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has directly and indirectly turned large sums of money over to these two enemies. The Netanyahu government directly provided funds. For example, a week before Oct. 7, Jerusalem effectively gifted the PA $92 million by halving the gasoline tax ($21 million) and transferring $71 million extra in tax funds. This amount came on top of another $90 million earlier in the year.

As befits a government shy about enriching its enemies, it relied more on indirect methods to help the Palestinians. It subsidized water, turned a blind eye to the theft of water and electricity, and approved development of the Hamas Marine Gas field. Israel helped in smaller ways too, with medical care and tourist permits to take children to the beach. A security source explained the rationale: "Perhaps instead of demonstrating, they'll go to the beach." That sums up the enrichment fantasy.

Palestinian women at the Tel Aviv beach; the solution? ® Daniel Pipes |

Israel provisioned Gaza even at times of war. During the Hamas attack on Israel 2012, when Hamas launched 1,506 rockets and missiles from Gaza, Israel sent 124 trucks with food and medicine to Gaza, kept the water and electricity flowing and continued to provide funds. During the Hamas-Israel war of 2014, the Israeli Electric Company sent technicians to repair electricity wires into Gaza destroyed by a Hamas rocket, risking the lives of its employees for the welfare of an enemy population.

JR: What strategy do you propose to achieve Israeli Victory?

DP: It requires replacing rejectionism with a benign set of ideas. I see this happening in two steps where the one creates the conditions for the other. First, eliminate the existing Palestinian quasi-sovereign institutions of the Palestinian Authority and Hamas, and replace them with Palestinian-run governing institutions under Israel's direct authority. Second, initiate a campaign to convince Palestinians to accept Israel, what I call the New Hasbara; surprisingly, Israel has never seriously tried to influence the thinking of West Bankers and Gazans. Time to start.