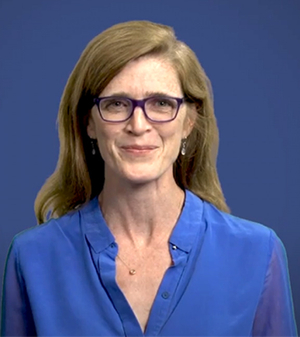

Former USAID administrator Samantha Power. |

Programs that we're running, the people we're depending on, in some cases, for life-saving medicine. ... Or if you're in Sudan and you have a child who's wasting away because of malnutrition, a miracle paste, a peanut paste that USAID provides brings that kid back from the brink of death – all of those programs are shuttered.

In plain English: Don't touch USAID!

Power, however, conveniently ignored a wide array of outrages engaged in by USAID, such as the $122 million it sent to groups aligned with designated terrorist entities, mostly on her watch. In other words, the full reconsideration of USAID now starting is very long overdue and urgently needed.

Foreign aid – that is, financial support from one country to another – became a significant phenomenon eighty years ago, at the end of World War II. Two factors prompted its growth: the devastation of the advanced economies of Europe and a desire to support or win allies against the backdrop of the emerging Cold War.

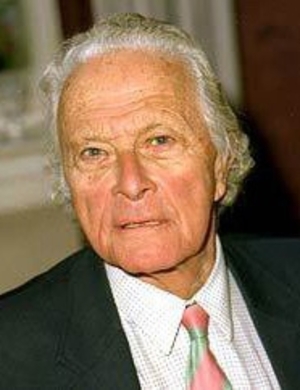

British economist Peter T. Bauer. |

The perceived success of the Marshall Plan in Europe and its equivalent in Japan created the expectation that money carefully invested would lift countries from poverty to wealth. Nearly a century of experience, however, showed this to be a fantasy; every country that has developed has done so on its own. Arguably, the free money that foreign aid represents distorts economies and impedes development.

Dismissing development aid, then, leaves three basic types of assistance: blankets (emergency), bombs (military), and bribes (political). Emergency aid amounts to charity, helping those in crisis. It is uncontroversial and relatively inexpensive but falls outside the purview of the State Department; perhaps the Interior Department should handle it. Military aid furthers Washington's goals by helping an ally fight; it belongs firmly in the Defense Department. Political aid, or incentivizing governments to adopt policies desired by Washington with regard to very specific goals, constitutes an important tool of diplomacy and therefore does belong in State.

Turning to the present uproar: The Trump administration has not ended foreign aid but questions whether it fulfills serves the American taxpayer. Such an accounting will find that USAID fails in three main ways.

First, in classic bureaucratic fashion, it tends to see the expenditure of funds as a metric of success. In one infamous example, it bragged about its investment to combat malaria in Africa but spent 95 percent of its funds on consultants and contractors, and only five percent on medicine, yet it took persistent questioning by Congressional committees to get USAID to admit that the figures it cited had no relations to what it actually did on the ground.

Albanian prime minister Edi Rama. |

A similar problem afflicts military assistance. When Pakistan and Egypt receive billions of dollars to stave off Islamist terror groups, they have an incentive to keep these groups alive. Personal corruption then gives military leaders even more reason to keep the Islamist threat alive.

Third, USAID ignores the negative impact of assistance on good governance. The Palestinian Authority, for example, realizing it would face no accountability, did not bother to govern responsibly. It used Western aid to fund murder and provoke retaliation, confident that donors would ignore the malfeasance and rebuild the infrastructure. A veritable firehose of funds overwhelmed any efforts by which the Palestinian Authority's subject population could hold its leaders to account.

Somalia, which received more than $1 billion a year for three decades, offers an even more extreme example. The autonomous region called Somaliland, making up Somalia's northern third, receives almost no assistance because international donors reject its secession. Yet, Somaliland's living standards and security far exceed those of Somalia. The unrecognized state even became the world's first country to assure elections integrity with biometric iris scans.

To review: Blankets to the needy are inexpensive and non-controversial. Bombs to defeat common enemies need to be done with caution, so as not to raise problems of self-interest and moral hazard. Bribery must never be decided by an ambassador or an USAID project director but much higher up, best by the National Security Council, and only in rare cases, lest countries expect payment in lieu of mutual cooperation.

In sum, foreign aid has utility but – like any charitable enterprise – must be handled with great care.

Mr. Pipes is president of the Middle East Forum. Michael Rubin is MEF's director of policy analysis. © 2025 by the Authors. All rights reserved.