President Clinton described the signing of an agreement by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as a "great occasion of history." Yasir Arafat called it an "historic event, inaugurating a new epoch," while Israel's Foreign Minister Shimon Peres called it no less than "a revolution." As though to confirm this extravagant view, American newspapers devoted as many as seven full pages to the White House ceremony while television offered hours of uninterrupted programming.

An enthusiastic crowd attended the Oslo Accord signing ceremony on the White House lawn. I was not one of them. |

But a nagging question remains. Was it really such a major event? Probably not, and for two reasons. Arabs have for the most part repudiated Arafat's act of compromise; and Palestinians are not - despite the enormous attention paid them - the key actors on the Arab side of this drama.

To begin with, many Palestinians and Arab rulers have denounced the Rabin-Arafat accord, few have supported it. Palestinian opponents divide into several types: fundamentalist Muslims, who predominate in Gaza; radical leftist organizations based in Damascus; and rebellious elements within Arafat's own group, Al-Fatah.

The fundamentalist Muslim groups - Hamas and Islamic Jihad for the Liberation of Palestine - absolutely and vehemently reject the accord; while they have reached an apparent agreement with Arafat not to wage an internecine war, they have also done their best to undermine the accord through a series of terrorist acts. And that's just the start. Similarly, all ten PLO groups in Syria reject the accord. These include George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Ahmad Jibril's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC); Na'if Hawatma's Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP); Abu Nidal's Fatah Revolutionary Council; and Abu Musa's group.

Even within Fatah, Arafat's own organization, the accord inspires profound unease. Many of Fatah's leading figures have denounced it, including the organization's number-two man, Faruq Qaddumi; its representative in Lebanon, Shafiq al-Hut; and the poet Mahmud Darwish. Basically, only Arafat and his aides support the pact; and they cannot impose their will on the many Palestinian leaders who do not. This explains why only eight of the eighteen members in the PLO's Executive Committee voted in favor of the accord. It also recalls Shimon Peres' choice observation back in 1988 (when he spoke more candidly about these matters): "There is nothing more fake than the PLO; there is no eel slicker than Arafat. He has no control over the PLO, Na'if Hawatwa, or George Habash."

What about the Palestinian masses? Despite the parades and flag-waving in recent days, there's not much reason to be hopeful. Palestinian political life has long had a self-acknowledged radical quality verging on the anti-rational. A Palestinian activist explained this in 1991 when attempting to explain his confidence in Saddam Hussein beating the U.S.-led coalition: "When you believe in what you are doing, you don't think about the consequences." As'ad Abd ar-Rahman, a member of the Palestine National Council, put the matter even more explicitly: "We [Palestinians] are desperate. We are not in the mood for rational discussion."

So much for the bad old days. Does the future look brighter? Israel's Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin counts on the PLO-controlled area turning into an economically vibrant and politically stable state, hoping that once Palestinians become prosperous and bourgeois, they will lose their taste for radical ideologies and violence. Maybe; but the Middle East boasts plenty of rich and conservative societies ruled by extremely bellicose regimes (think of Libya, Iraq, and Iran). In this part of the world, leaders count much more than followers, and most Palestinian leaders remain unreconstructed.

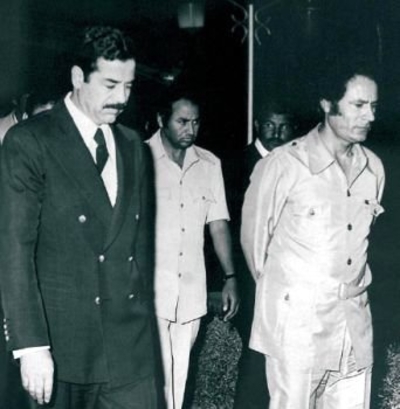

Saddam Hussein (L) and Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi: In the Middle East, rulers count much more than followers. |

Turning to the Middle Eastern states, two medium weights support the accord, Egypt and Saudi Arabia and two heavyweights oppose it, Iran and Syria. The Iranian regime has ferociously denounced the accord and vowed to oppose it with its violent legions among the Palestinians and in Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt. President Asad of Syria also wants to undo the accord, but he plays a more coy game, announcing he will neither fight the accord himself nor restrain those who do want to oppose it. This subtle policy permits him to deploy the PLO factions in Damascus without antagonizing the U.S. government. He's a smart one, Asad.

Such powerful opposition is likely to limit the importance of the Rabin-Arafat compromise. In this context, it's worth remembering that Anwar al-Sadat also hailed the Egypt-Israel peace treaty in 1979 as "an historic turning point." But it was less that than a change of lanes. Because Palestinians and Arab leaders did not follow Sadat in making peace with Israel, that treaty did not end the Arab-Israeli confrontation; it merely altered the terms. For example, just as Egypt retreated from the conflict, the brand-new revolutionary regime in Iran jumped in and effectively took Egypt's place as one of the states most dangerous to Israel's security. The new accord is likely to be similarly limited.

The fact that fundamentalist and radical leftist Palestinians reject Arafat's turn toward peace points to a larger issue; Palestinian leaders are not masters of their own destiny, but rely to a great extent on the states of the Middle East. They do not make the ultimate decisions of war and peace; states do this. They control neither the fighter planes in Syria nor the missiles in Iran nor even the knives of the fundamentalist Palestinians. If Iran and Syria decide to continue the conflict against Israel, it goes on.

In April 1990 I conjured up in print a fantasy: suppose Arafat and the Israelis reach complete agreement on Palestinian self-government, what would change? "Not much. Syrian missiles and Jordanian soldiers would remain in place, as would the cold peace with Egypt, while anti-Arafat elements of the PLO would continue to engage in terrorism. The intifada would probably go on, even if weakened." I'd change some words now, but the basic point remains valid: states are the key actor in the conflict with Israel.

On the other hand, what if Hafiz al-Asad signed a peace treaty with the Israelis? "In that case, the inter-state war would come to a virtually end because Amman would immediately follow Damascus's example. Some of the Syrian-backed Palestinian groups would come to terms with Israel, as would Arafat. Even though Palestinian extremists would continue to riot, the conflict would become much less dangerous."

Because Yasir Arafat cannot impose his will either on Gaza or on a single state, he is ultimately more a media figure than a power broker. If he and his lonely band are left out on a limb, as appears to the case, his accord with Israel will probably wither. If it does succeed, it will be not a solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict but an interim agreement with yet many hurdles to overcome.

Mr. Pipes is director of the Middle East Council, a division of the Foreign Policy Research Institute.