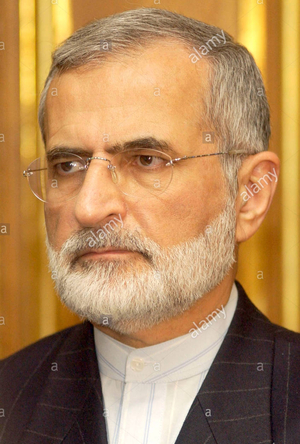

Iran's Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi. |

has no intention, nor is it going to take any action whatsoever, to threaten the life of the author of The Satanic Verses or anybody associated with his work, nor will it encourage or assist anybody to do so. Accordingly, the government dissociates itself from any reward that has been offered in this regard and does not support it.

Pronouncing this statement a momentous change in Iranian policy, Foreign Secretary Robin Cook responded: "These assurances should make possible a much more constructive relationship between the United Kingdom—and I believe the European Union—[and] Iran, and the opening of a new chapter in our relations." He went on to announce the UK's resumption of full diplomatic relations with Teheran, broken since 1989.

The British foreign minister was hardly the only one to construe the Iranian statement as a decisive retreat from the February 1989 edict, signed by Ayatollah Khomeini, that condemned to death "the author of the book entitled The Satanic Verses ... and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content." Amid the general jubilation, Rushdie himself, who has spent the last ten years in semi-seclusion, was particularly euphoric. "It's a breakthrough and it's over. ... There is no longer any threat from the Iranian regime. The fatwa will be left to wither on the vine." Best of all, Rushdie added, "It seems this has been done in Iran with consensus. There doesn't seem to be any opposition to it."

Is this true?

The statement by the Iranian foreign minister, Kamal Kharrazi, had three carefully crafted components. First, Teheran would not attempt to kill Rushdie or others connected with The Satanic Verses. Second, Iran would not encourage others to do so. Third, Iran dissociated itself from the reward of up to $2.5 million that had been offered by the 15th Khordad Foundation for Rushdie's murder.

As it happens, far from being a "breakthrough," not a single one of these assertions said anything new. For years now, Teheran has informed the United Kingdom and other European states that it has no intention of carrying out the sentence passed by Ayatollah Khomeini. Already in June 1989, just days after Khomeini himself died, an unofficial Iranian spokesman in London announced that while the death threat would not formally be withdrawn, Teheran was "prepared to let the matter drop." Several months later, Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati made this position formal when he suggested that West European governments "don't need to connect the question of Salman Rushdie to political relations between Iran and those countries."

The Iranians have repeated this formulation time and again over the ensuing years. In perhaps the strongest such reiteration, an official of the foreign ministry declared in December 1997 that the Rushdie edict was "a purely religious matter, with which the Iranian government has nothing to do." The government of Germany was proud to claim this statement as one proof of the alleged benefits of its "critical dialogue" with Iran.

Similarly with the second point—encouraging others to kill Rushdie—and similarly again with the third point concerning a financial reward. From both, the Iranian government has conspicuously taken its distance. Thus, in May 1997, to cite but one example, Iran's ambassador to Hungary clearly stated that "Iranian leaders have never said or suggested that someone should kill" Rushdie. And when, in February 1997, the 15th Khordad Foundation announced that it would raise its prize from $2 million to $2.5 million, President Hashemi-Rafsanjani went out of his way to respond that "this foundation is a nongovernmental foundation and its decisions are not related to government policies."

If Kharrazi's statement merely recapitulated longstanding Iranian policy, of greater note was what it did not say. Kharrazi neither repudiated the 1989 edict nor limited its scope; he neither took issue with it nor even contested its validity as the basis of government policy. He only gave assurances that the Iranian authorities would not carry it out.

The fact is that, whatever Teheran's diplomats might say, among the Iranian elite there is near-unanimous agreement that the edict against Rushdie is a permanent sentence, one which both constitutes government policy and at the same time is beyond the competence of government to affect.

The brand of Islam practiced in Iran distinguishes between two types of religious pronouncements, a fatwa and a hukm. The former remains valid only during the lifetime of the religious authority who issues it; the latter continues in effect beyond his death. Despite the Western habit of referring to the edict against Rushdie as a fatwa, Iranian spokesmen have universally regarded it as a hukm. Thus, Ayatollah Abdallah Javadi-Amoli in February 1997: "This is not a fatwa which died with the death of the religious leader who issued it. . . . It is a hukm which is permanent and it will stay in place until it is carried out."

There seems to be no dissent among Iranian political leaders that they are powerless to repeal this "unchangeable religious decree" (to quote the deputy chairman of the Iranian parliament's foreign-affairs committee). Only Khomeini could have taken such a step, and he specifically refused to do so. According to the Iranian media, Khomeini admonished his successors before his death never to retreat from the hukm, no matter what the pressure: "It should not be permitted for this edict to become a diplomatic issue subject to negotiations." Artfully-worded statements to Western leaders notwithstanding, his heirs have faithfully followed his instructions.

Kharrazi's own understanding of the matter does not differ in the least. Not only did he acknowledge on September 24 that he was saying nothing new, he underlined the point a week later: "We did not adopt a new position with regard to the apostate Salman Rushdie, and our position remains the same as that which has been repeatedly stated by the Islamic Republic of Iran's officials." His words were echoed by an endless series of comments by Iranian politicians, theologians, and news analysts. One newspaper editorialized that "the issue of Rushdie will end only with killing him and all the elements associated with the publishing of the book." A leading ayatollah declared that executing Rushdie remains a duty incumbent on all Muslims "until the day of resurrection." In parliament, 150 of the 270 members signed an open letter stressing the edict's utter irrevocability. The Association of Hezbollah University Students announced it would add a billion rials ($333,000) to the reward for Rushdie's assassin, theological students and clerics in the holy city of Qom pledged a month's salary as an additional bounty, and a small village in northern Iran sweetened the pot by offering his executioner ten carpets, 5,400 square yards of agricultural land, and a house with a garden.

In short, the threat to Salman Rushdie is as great as it ever was. Indeed, it may be even greater now that he and others have convinced themselves it has ceased to exist. For just as there is no reason to think anything in Iranian policy has changed, there is no reason to believe Kharrazi's assurances. There have been many previous such assurances, and they have hardly prevented attempts on Rushdie's life, including, as he himself revealed in 1997, on the part of Iranian government agents.

Nor are Iranian agents the only potential threat. Fundamentalist Muslims around the world hold Ayatollah Khomeini in uniquely high regard; for them, the death sentence against Rushdie remains a shining legacy, far beyond the control of apparatchiks in Teheran. As the Iranian media emphasized, the edict "is not confined to Iranians alone"; "every committed and free Muslim feels obliged to defend it." Ayatollah Hasan Sane'i, head of the 15th Khordad Foundation, has gone still further: the reward, he has said, "will be paid when the edict is carried out by anybody, Muslim, or non-Muslim, or even Salman Rushdie's bodyguards."

In his voluble reaction to Kharrazi's statement, Rushdie may actually have exacerbated Muslim feelings against him. Gratuitously retracting a statement he had made in 1990 affirming his own Islamic faith, he insulted his enemies ("dinosaurs [who] represent absolutely nothing"), called The Satanic Verses "an important part of my work," and predicted that "the whole issue will now very rapidly fade into the past." To quote the warning of an Iranian newspaper, this very optimism on the part of Rushdie and his supporters "may even pave the way for a speedier execution of the sentence against him."

The plain truth is that neither Foreign Minister Kharrazi nor, by extension, President Mohammed Khatami clearly speaks with authority for the government of Iran. Time and again, it has become apparent that this president, however "moderate" his own views—and even that is a matter of degree—is not the ultimate power in Teheran. That belongs to the person who now fills Khomeini's position as Iran's spiritual leader—namely, Ali Hoseyni Khamene'i, a politician who has steadily supported the edict and whose hardline followers retained decisive control of Iran's ultimate decision-making body in elections held in late October.

Which only raises the question, why did Kharrazi's statement have so apparently electrifying an effect on Britain and other Western governments? The answer is that governments have the ability, when they wish, to turn non-news into news, and in this case, for reasons of its own, London clearly wanted to do just that. As the Associated Press correctly surmised, "Kharrazi and Cook sought to portray the move as something new and significant as a way to improve ties that have remained strained over the [Rushdie] issue."

And why this push to improve ties? Here, one can hardly do better than to quote Salman Rushdie himself in 1997: "When it's Danish feta cheese or Irish halal beef against the European Convention on Human Rights, don't expect free expression to win." The lure of the Iranian market, however small, is a mighty one. Rushdie has been an impediment to European governments wishing to enter that market. Now, in collusion with Teheran itself, they have found a way to brush the impediment aside.

The Europeans are not alone. Like their British counterparts, American policy-makers, too, have allowed their desire for oil contracts and oil pipelines to cloud the nasty reality, which is that repression, terrorism, and territorial aggressiveness continue to be hallmarks of the Iranian regime, augmented lately by the push to acquire weapons of mass destruction. In early 1998, the U.S. State Department's annual report on terrorism noted correctly that even under President Khatami, no change had occurred in Iran's pattern of violent conduct, and concluded that Iran remains the world's principal state sponsor of terrorism. Higher-ranking State Department officials would have none of this, and simply brushed the report aside. Similarly, the fact that Iran's missile program has accelerated under Khatami has not been permitted to affect the Clinton administration's push for rapprochement with the Islamic Republic.

Just as Rushdie's delusions place him in greater danger, so do parallel delusions among American policymakers place us, and the world, in greater danger. The sanctions on Iran have been our functional equivalent of bodyguards: passive, open-ended, inconvenient, even annoying, but, under the circumstances, better than nothing at all, and better than any alternative that is likely to be pursued. Just so, Iran's missiles and weapons of mass destruction are the functional equivalents of lurking assassins. Swooning over President Khatami's improved tone, or Foreign Minister Kharrazi's cautious equivocations, will no more protect us from those threats than Salman Rushdie is likely to be protected by his giddy insistence that Ayatollah Khomeini's edict is no more.