The German weekly Der Spiegel states, "Never before in modern history has a country so dominated the earth so totally as the United States does today." Looking back even further, columnist Charles Krauthammer wrote recently in The New Republic that the United States "the most dominant power relative to its rivals that the world has seen since the Roman empire."

Objective Realities

Actually, they are understating the case: The United States enjoys a might without precedent in human history. This country spends an order of magnitude more on its forces than any other. The U.S. is the only participant in the "revolution in military affairs," giving it whole classes of weaponry (such as stealthy planes) beyond the competence of others, and it has a force projection that extends to nearly the entire globe. No state can contest it in conventional or non-conventional terms.

The U.S. B-2, a stealthy aircraft. |

One might think that this muscle simplifies America's strategic landscape for, in theory anyway, the United States can on its own take on virtually any task without help from anyone. It can get rid of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, destroy the North Korean arsenal or even contain Chinese ambitions. Such niceties as United Nations endorsement, troops from Europe, money from Japan, or bases from Saudi Arabia are helpful but not necessary.

Well, that is the theory, anyway. And were Seattle to be invaded, it would be fact; in an emergency, Americans would again be of one mind and our power would no doubt win out. But in the meantime, with the use of force always optional, Americans tend to be enormously divided among themselves. Everything is now voluntary: Do we wish to be global policeman or withdraw into a shell? Get involved (as in Kosovo) to save lives or adopt a strict standard of national interests? We can do pretty much what we like. And sometimes that is not very much.

The reality partly reflects the age-old divide between those who see the United States as a light unto the nations and those who would have it setting its own house in order. It also reflects the yawning liberal-conservative gulf that emerged at the time of the Vietnam War. And the absence of a Soviet-American great game makes each issue that much more difficult to decide. Angola and Afghanistan fit into a global chess game, but Haiti and Bosnia are self-contained.

Our current behavior patterns reflect the peculiar American habit of capping victory abroad by rushing home. We did this after the World Wars I and II, then stayed true to form after the Cold War. Following the Soviet implosion we chose not to create an empire but to reduce military spending, not to dominate our neighbors but to increase trade with them (NAFTA), not to start foreign adventures but to fix the chronic problems of American life - the race problem or the tax system. Americans spend money on arms with reluctance and send troops abroad with deep misgivings.

Most of all, the end of war always allows us the chance to engage in some Constitution-sanctioned pursuit of happiness (Roaring '20s, Booming '50s). In the '90s we surf the Internet, explore new sexual identities and follow the Dow index. It seems that the national mission is to perfect our tennis backhand or mix the ultimate barbecue sauce - certainly not making the world safe for democracy. We would rather defeat a rival sports team than Castro or Saddam.

Most of all, the end of war always allows us the chance to engage in some Constitution-sanctioned pursuit of happiness (Roaring '20s, Booming '50s). In the '90s we surf the Internet, explore new sexual identities and follow the Dow index. It seems that the national mission is to perfect our tennis backhand or mix the ultimate barbecue sauce - certainly not making the world safe for democracy. We would rather defeat a rival sports team than Castro or Saddam.

Subjective Realities

So, while objective indices point to unparalleled American power, subjective realities paint a much murkier picture of confusion, insularity and reluctance.

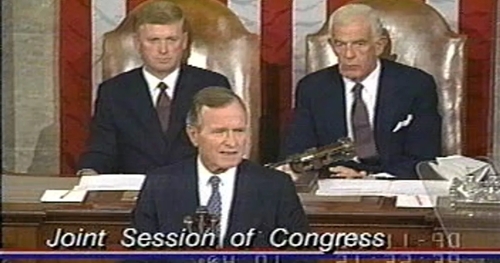

All of which utterly baffles the outside world. Non-Americans, whether as near and dear as Canadians or as remote as North Koreans, cannot fathom and do not quite trust the apparent self-absorption of Americans. Even our closest allies (not to speak of more than a few alienated Americans) read the seeming American lack of interest in overseas expansion as a ploy. They hunt to interpret the real agenda, locate the underlying imperial motives, unmask the hidden conspiracy. Their fevered imaginations allow them to see international institutions - the Security Council, International Monetary Fund, World Bank - turning into pawns of American hegemony. They take President [George H.W.] Bush's one-time remark about a "new world order" - a dimly conceived, anodyne notion about politics after the Cold War, lacking any operational importance - and trumpet it as an ominous and programmatic lifting of the veil.

George H.W. Bush delivering his "new world order" speech" in 1990. |

This suspiciousness usually reveals what psychologists call projection: Foreigners assume Americans are doing what they would do with our power - impose their will on others. They imagine that the United States, finding themselves in the catbird seat would act like they would: Expand territorially, build spheres of influence and create exclusive trade zones. They cannot believe that the United States is not doing the same as they would.

Americans tend to laugh off such misinterpretations, dismissing them as insignificant blather. Blather yes, but not insignificant. This outlook goes far to explain why the Russian Parliament fears an American takeover of their country, why the Arab "street" believes in an American conspiracy against Islam, and why Japan's media blame Americans for its economic troubles.

Every last rogue regime (North Korea, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Libya, Cuba) bases its propaganda on an aggressive American plot; they do so because this approach offers their best chance of winning international sympathy. Fidel Castro and Saddam Hussein have gone so far as to make this their main shield against the United States.

This pervasive suspiciousness matters in another way, too: The opinion of non-Americans about America affects American actions. A review of events since 1990 suggests that what makes or breaks American willingness to take action abroad has relatively little to do with national interests (such as preventing an enemy from being acquiring weapons of mass destruction) or the popularity of a cause. Instead, it reflects foreign support. Without the endorsement of the U.N., Europe, Japan, Saudi Arabia and others, Americans find it nearly impossible to deploy forces abroad. That explains the persistent emphasis in Washington on Security Council or NATO resolutions; we lack the resolve to make unilateral decisions, even if our power entitles us to do so.

Foreign Opinion

Foreign opinion has a strangely important role in American policy, rousing Americans to action or damping it. Take a specific case - ousting Saddam.

When will Americans dispose of this monster? |

Thus does the deep suspicion and wide hostility that much of the world harbors toward the United States have an enormous impact, serving as a brake on American actions abroad. In theory, if the outside world should have little impact on American decision making, instead, it in fact defines much of America's strategic landscape.

Conclusion

For the United States to pursue an active and successful foreign and security policy, it must convey its purposes and goals to others around the world, rather than letting the rest of the world dictate our goals. This will not be easy, particularly because it means getting away from conventional policy discussions about throw-weights and trade balances, and instead conveying the spirit of what it means to be an American, i.e. living well and leaving others to go their own way. Only when the rest of the world better comprehends our utterly mysterious country will we again have a successful foreign policy.

Daniel Pipes is director of the Middle East Forum and author of Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes, and Where It Comes From (Free Press).

Related Links

Karim El-Gawhary questions the effectiveness of air strikes in "Ending or Maintaining the Conflict: Military Air Strikes." The Arab Daily Chronicle mounts charges against CNN for improperly using the word "terrorists" to describe Hizballah. Protestant evangelicals take a stab at foreign policy. The World Constitution and Parliament Organization's Constitution for the Federation of the Earth calls for a democratic world government that would replace the United Nations. Watch and listen to the BBC's latest coverage of the air strikes in Kosovo.