The May 17 Israeli election does not present a happy prospect for someone like myself who believes that most Arabs have not abandoned the dream of destroying Israel. I do not have a dog in this race. Here is why:

More Israeli Concessions, No Arab change

Back in September 1993, Israel and the Palestinians reached an agreement on the White House lawn that boiled down to a simple exchange: benefits for peace. Israel granted the Palestinians a wide variety of benefits, especially control over their daily lives; in return, the Palestinians were supposed to relinquish their bellicose intentions against Israel and accept it as a permanent, sovereign Jewish state.

Although mutual in appearance, this agreement (nicknamed the "Oslo accords") actually was not really parallel. Then-Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin promised actions, Palestinian Authority (PA) leader Yasir Arafat promise a change of heart. Israel's concessions were concrete and irreversible, while the Palestinian ones were subjective and conditional.

Israel materially fulfilled its promises. Some 97% of Palestinians who in 1993 lived under Israeli rule now live under Arafat's PA. In contrast, the Palestinians have not kept their word.

In myriad ways, Palestinians signal a continued intention to destroy the Jewish state. Politicians still speak about jihad for Jerusalem; maps show a Palestine not alongside but instead of Israel; children are made to sing on television about becoming "martyrs" against Israel.

From the time of the Oslo accords' signing until the election in May 1996, no one noted these troubling facts more eloquently than Benjamin Netanyahu, leader of the Likud Party. Hammering away at the record of Palestinian non-compliance in his electoral battle against then-Prime Minister Shimon Peres, Netanyahu promised that on taking power, the one-sided concessions would end. On this basis, he was elected prime minister.

Well, Netanyahu himself has been guilty of some non-compliance. During his three years as prime minister, he has slowed the pace of concessions, and he made concessions more reluctantly. But the essentials of the Labor Party policy remain in place.

Netanyahu has not made scrupulous Palestinian adherence to signed promises a precondition to Israel's making new concessions. To the contrary, despite the PA's innumerable trespasses, he has signed two new agreements with it, the Hebron and Wye accords, giving the PA yet more benefits in return for more phantom promises of a change of heart.

The Real Netanyahu

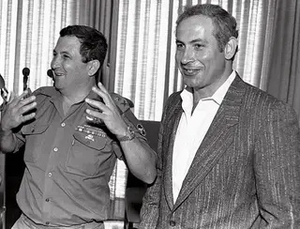

Ehud Barak (L) and Benjamin Netanyahu. |

In other words, both men endorse an essentially unilateral series of concessions by Israel. They differ in tone and in pace (Barak would move more quickly and smilingly than Netanyahu), but not in direction.

That Barak should accept unilateral concessions is not surprising. In the tradition of Rabin and Peres, Barak believes Israel must shoulder the main burden of ending the Arab-Israeli conflict, so he pays relatively little attention to Arab non-compliance with treaties. But how can Netanyahu, heir to Zionist Ze'ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky and Menachim Begin, a man widely portrayed as a "hard-line" prime minister, accept this premise?

Benjamin Netanyahu (L) and Bill Clinton. |

More profoundly, however, Netanyahu most closely resembles not Clinton but former U.S. President Richard M. Nixon. Both these politicians arouse intense hostility on the left without actually carrying out the right's program.

As with Nixon, journalistic, academic and artistic elites harbor a wildly irrational hatred of Netanyahu - even though he has far from implemented a conservative program, only a me-too liberalism. Nixon pursued wage and price controls, affirmative action, détente with the Soviet Union and the opening to China. Netanyahu has left the socialist state in place and has a negotiating record with the Arabs rather similar in substance, though not tone, to that of his Labor opponents.

Seeking a Prime Minister of Principle

That is why this conservative observer finds the choice between Netanyahu and Barak so depressing. In the short run, it is better that Netanyahu win, for the one-sided concessions will be fewer and slower. But for the long term, it may be that a Barak victory is better for the country.

Just as the defeat of U.S. President Gerald Ford in 1976 led to the emergence of a true conservative (Ronald Reagan) in 1980, so the defeat of Netanyahu may be the necessary catalyst for someone with solid principles to appear in the future who can truly safeguard Israel's security.

Daniel Pipes is director of the Middle East Forum and author of Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes, and Where It Comes From (Free Press).

Apr. 5, 2005 update: My conclusion above, that "the defeat of Netanyahu may be the necessary catalyst for someone with solid principles to appear in the future who can truly safeguard Israel's security" turned out to be correct. Barak defeated Netanyahu in 1999 and by 2001 Barak had so thoroughly discredited the "peace" approach to the Palestinians that, in reaction, Israelis elected Ariel Sharon as their prime minister. He truly did show "solid principles" for the first three years of his prime ministry, 2001-03.

Then, for reasons that no one has fully explained, Sharon switched sides, as I explain today in an article, "Ariel Sharon's Folly." This switch limits the benefits of but does not reverse my argument for wanting to see Netanyahu defeated. At least there were three solid years. On the bright side, perhaps Sharon's unexpected and unelected switch will again lead the electorate to turn to someone with solid principles as prime minister.